- The otsuzumi is a larger drum of the same basic type as the kotsuzumi but held on the knee as opposed to the shoulder. It also has a completely different sound that is sharper, almost metallic in quality. Can you tell us about the difference between the two drums?

-

The kotsuzumi and otsuzumi are two different types of drum but both are very sensitive instruments. (Being made of natural materials like wood an skins) the Japanese traditional instruments are greatly affected by environmental factors like humidity. Whereas the kotsuzumi performer accommodates for changes in humidity by applying saliva or breathing moist breath into the drum, with the otsuzumi, in contrast, we take care in making sure that the drum is sufficiently dry. To do this, we put it through a drying process that dries out the drum skin for about two hours before we play. The otsuzumi skin is horse skin and heating it to dry it our damages the cells of the skin gradually, and the fact that that it is stretched onto the drum also causes stretching of the skin that weakens it. After four or five uses the quality of the sound drops to the point where it has to be changed. So, we constantly have to be buying new skins. And give the effects of the constantly changing humidity, you really never get the same sound out of the drum twice. It is different every day.

When we strike the otsuzumi, we are using the central axes of the body, the pelvis, the back and the chest as the swing axis so that the drum can be hit with a snap from the wrist without tension in the fingers. If the axes of the body are used properly it is easy to swing through with a good slap to the drum. The sound of the otsuzumi comes out the back of the drum. The sound travels through the cylinder of the drum, through the back skin and then reflects off the back wall of the stage where the pine tree is painted. That is the sound that you hear in Noh. - The four-instrument ensemble that performs the musical accompaniment (hayashi) in Noh is made up of the three percussion instruments of the otsuzumi, kotsuzumi, the taiko drum and the flute. What is the role of this four-instrument ensemble in the music theater that is Noh.

-

If the orchestra in opera is the actors’ voiceless voice, then that is close to the kind

of role the hayashi plays in Noh. It is more than simply an accompaniment. The abstract voice calls of “yoh” and “hoh” that we members of the hayashi make combine with the simple “chone” sound of the otsuzumi, the “pone” sound of the kotsuzumi, the “ten” sound of the taiko and the “hee” of the flute to create that kind of voiceless voice for the actors. In other words, the role of the four-instrument ensemble in Noh is to give expression to the cries of the soul of the actors.

We call the “playing” we do in the Noh hayashi “ hayasu ,” which means that we are in fact performing two roles, one as a musical accompaniment and another that is something similar to the role of a “third character” in the play by filling in with our calls the “words” unspoken by the main character ( shite ) and the supporting actor (waki). - To me the vocal calls of the otsuzumi player are a very attractive and fascinating part of Noh, sometimes sounding like an effective theatrical element and sometimes carrying the listener off into a very abstract realm.

-

The role of the

shite

is to perform the dance and the recitation, and the parts that cannot be said by the shite are primarily chanted by the

jiutai

chorus. This is similar to the chorus in ancient Greek tragedy. The jiutai chant is sufficiently explanatory in its wording, so there is no need for the hayashi team to use words. Still, there are limits to what can be expressed in the recitations of the jiutai chorus and the narrative recited by the shite. So, the role of our abstract calls is to give an added a sense of reality to the words and the dance movements.

In specific terms, there are places in certain plays where the sounds of our calls are varied in order to represent the sounds of a rain scene or a snow scene. It is a matter of using high, middle and low vocal sounds to create the desired effect. The rest is perhaps close to what Danjuro IX called “the art of conveying unspoken messages. There are times when I concentrate on “rain” for instance in such a scene and try to vary the vocal effects accordingly. - In the orchestra analogy, the shite of Noh is said to be the equivalent of the conductor. If so, does that mean that the four-instrument ensemble follows the directing of the shite.?

- It is true that the shite is the main character in the Noh play, but we do not perform according to the shite’s lead or direction, it is rather a situation in which the four-instrument ensemble and the jiutai chorus move the actors, which includes the shite, waki and Kyogen actors. The equivalent of the concertmaster among the four members of the ensemble is the otsuzumi and the concertmaster of the chorus is the leader called the jigashira . During the play it is these two concertmasters who lead the overall flow of the action and music. Since the shite is performing, he cannot give verbal directions to the hayashi members or the jiutai chorus. So we (the otsuzumi and jigashira) watch the timing ( kuraidori ) of the shite’s spoken lines and also the dance movements themselves and send messages back and forth to each other with our vocalizations. This kuraidori can be thought of as the pacing of the performance. The pace (kuraidori) of the shite’s performance is different every day, depending on the physical condition, the mental state and the answers that he has arrived at in his practice/rehearsal concerning how he wants to perform the given role. Therefore, if we perform the same play for 25 days in succession the length will never be the same on any two days.

- In Noh, the performers from the different disciplines never practice together, an the enter a performance run having rehearsed together only once. It seems almost unbelievable that a high-level performance can be brought together with just one rehearsal.

-

The reason we are able to do this is because the same script has existed and used for more than 600 years. Noh functions according to a complete “division of labor” between the shite, waki, Kyogen and hayashi disciplines (and the four instruments of the hayashi are also separate). These families in which these disciplines have been handed down have traditions that have continued for more than 600 years. And within each of these traditions, there are musical scores and performance methods that have been handed down from one generation to the next. So, the practitioners (performers) from each of these traditions practice and train in their own parts only and then come to that single rehearsal and bring it all together. They have all done sufficient training from an early age to be able to do this. And, viewed from another perspective, the only ones who stay in this professions are the ones who are able to do this, to be able to jump right in after one rehearsal and perform at a high level with the other disciplines.

I would also add, that my practice for a given play is not a process of practicing the otsuzumi drum part, rather it is a process of reciting the script. This is the way my father taught me to practice. I memorize the entire play script. I get a sense for the pace of the entire play. From my past experience performing different plays I work on clarifying my image of the play. Besides this, I believe that watching other performers’ stages is also an important part practice. By watching other people perform, you can get ideas about how you would perform it differently.

In order to perform the part of the otsuzumi in Noh, you have to have a total grasp of the parts of the flute, the kotsuzumi, the taiko the narrative and, if you want to be fully ambitious, the dance of the shite as well. If you don’t know the feeling of the flute, you can’t play the drum part of a dance. If you don’t know the feeling of the kotsuzumi you will be anxious about how he will receive the otsuzumi. The otsuzumi and kotsuzumi are sometimes spoken of in terms of a marital relationship, with the otsuzumi as the husband and the kotsuzumi as the wife. It is no good if everything is decided based on the feelings of the husband. The husband has to understand the heart of his woman.

You won’t learn much by practicing the otsuzumi alone by yourself. You have to wait until the actual play performance before you can really perform. You just have to spend your time thinking about how you are going to interpret the play in your performance and how you will use your calls. Your hand has already learned all the technique you need, so you save your hand for the actual performance. The otsuzumi is an instrument that takes a toll on the hand in direct proportion to how much you play it. Considering the number of performances I am doing now, I don’t want to use my hand for practicing. I have decided that I will gradually do the damage I must do to my hand in performance, not practice. - When did you first begin to feel this way?

- I was seven when I first realized that I had to take care of my hand. Since you have to learn the technique, I practiced very hard until I was in high school. And, although I now use a protector that we call finger skins, I often didn’t use them and beat the drum barehanded when I was in my teens in order to strengthen my fingers. I was 16 when I realized that I would ruin my hand if I kept practicing so much.

- I would imagine that there are times when you get to the rehearsal before a performance and find that the image of how you are going to perform a play turns out to be different from that of the shite. What happens then?

-

It depends on the case. If it is a highly accomplished actor (shite) that everyone respects, I adapt to the will of the shite. In the end, the shite is a conductor who doesn’t use words, asking about his intentions beforehand is an important prerequisite. But, if I find that I can’t agree with some things, there will be times when I make requests for some changes. However, it is the otsuzumi and the jigashira who actually move the performance along once it is underway.

The rhythm of Noh is an eight-count beat. In terms of Western music it is 4/4 beat or an 8/4 beat. Within this beat, the otsuzumi plays the odd-numbered beats and the kotsuzumi the even numbered beats. In other words this means that the otsuzumi provides the first beat, and the kotsuzumi provides the ending beat of the 5/4 rhythm or the 8/4 rhythm. The otsuzumi gives the lead beat and the kotsuzumi receives it, or answers it. The otsuzumi creates the initial notes, whether it is the “yoh” call or the beat of the drum, and also the interval between the two. In this way, the otsuzumi is setting the initial tone and timing of the phrase, and that is what makes it so interesting to perform.

Among the four instruments of the Noh ensemble, the role of the kotsuzumi is to “fill out” the sound [that the otsuzumi has initiates]. The taiko drum is played in double-time, providing both upbeat and downbeat to dominate the rhythm. In that sense you might consider it to be the heartbeat of the hayashi. As for the flute, if the kotsuzumi “fills out” the sound, the flute “decorates” it or highlights it. And the otsuzumi is the initiator of “circumstance” for each of these parts and the creator of the overall framework within which they fit. So, the otsuzumi has to be strong and decisive, otherwise the musical accompaniment and the flow of the play as a whole will not come together successfully. - The calls that are shouted out in the hayashi are loud to the point of even being noisy, close to a percussion instrument. Do you take measures to modulate the calls you make in any way?

-

In fact, most of the measures I take for modulation or expressive variation concern these calls, rather than the sounds I make with my drum. There are many ways in which the calls must integrate with the narration (recitation) of the play. For example, our sounds are divided basically between high, medium and low sounds, which are referred to as

ryo-chu-kan

in the Japanese tradition. And, if the next line coming in the recitation is a high (

ryo

) phrase, I will hit a high note and then make a call that leads into it by saying in effect, “Here comes a high phrase.” The role of the otsuzumi within the hayashi is to give the initial leading note and beat, so I take this role into consideration with my calls as well as my drum beats and their tone. And there are also times when I may come in with a low sound even if the coming recitation is a high phrase and in that way create a sort of push-and pull dynamic. There are also times when I come in with a more abstract, floating type of call regardless of the recitation that will follow. In fact, the decisions about what kind of voice to make each call in is based on trial and error for me.

I was once told by my old master, “Your use of the calls is deceptive. You don’t need to use so many clearly different voices. One sound is enough.” From my point of view, I think I am traveling the same path that my Master did when he was young. When I listen recordings of my father’s performances from his younger years, he is clearly changing the sound of his voice with different scenes. As a performer like him gets older, the techniques he acquired in the trials and error of his youth are gradually polished away, in a positive sense. I guess there is a need for a performer in the world of theater to add variation and “fatten” your repertoire of vocabulary and technique until your mid 40s. But when you pass the age of 50 you begin the process of polishing away the excess until your art begins to shine. Doing as you are taught is a stage that should end before the age of 20. - Since sons of the Noh and Kabuki families begin their training at a very early age. So by your age in your 30s you already have a career of over a quarter of a century.

-

That’s true. It has already been 30 years since I began training. For an athlete my age is around the age when they reach their peak in terms of physical prowess, and it is all downhill after that. But in our profession the longer you live and perform the more you can refine your art, so I look forward to the years ahead. I feel truly fortunate that I found a profession where I can work for the full span of my life and I will not know what kind of performer I have been until the day I die.

And that is not all. There is also the art of aging. Zeami, a cofounder of Noh theater, said “Like an old tree can bloom.” In other words, he hoped that people could continue to blossom even in old age. But a performer past the age of 70 with a voice that is not as strong as it used to be and less freedom of movement in the old joints can continue to blossom and bring inspiration to people with his dance, no matter the constraints or how stripped to essentials it may be. That is the kind of world Noh is. In his theoretical book Fushi Kaden , Zeami wrote the words “ Nenrai Keiko no Jojo .” I interpret it to say if you haven’t achieved some degree of fame, technique and character by the age of 34 or 35 you will only go downhill from there, so it is best to give up the effort. I trained until now to reach this first goal and now I want to work toward the next goal, which is the fill out the bones of my art with some more meat by my mid-40s. - We hear that you call yourself an actor rather a musician. Why is that?

- I decided to stop thinking of myself as a hayashi musician. As long as I am performing on stage, I want to think of myself as an actor who uses the otsuzumi as an expressive medium in the play. As long as I am performing where the audience can see me, my line of sight, the movement of my hand, my posture and my facial expression are all parts of my performance. The otsuzumi player sits in the position that is most prominent from the viewpoint of the audience, so every posture and movement must be a thing of beauty. I believe that posturing and movement are in the realm of the actor.

- You come from a family where everyone is a hayashi musician. Do you think that when you began training at the age of three, was it of your own will?

-

My parents said, “Come sit in front of me [and learn how to play].” And that’s how it began. Considering the fact that I had been hearing Noh and Kabuki since I was in my mother’s womb, it was only natural. At that time my mother was an instructor in Kabuki

narimono

in National Theatre’s trainee program while also giving lessons to her own amateur students and supervising the practice of the Tanaka school apprentices. She would also go to see my fathers Noh performances and her father’s Kabuki performances, while also performing in Kabuki

geza

(musical, sound effects). So that was certainly a lot of input I was getting.

Besides that, when my brothers and I were small our mother often took us to see Kabuki and Noh performances. She would strap my younger brother on her back and have my youngest brother in one arm while leading me by the hand to go see the plays. She would have us sit inside the kuromisu —the equivalent of the Western orchestra box where geza performance takes place—or to the very back row of the audience and tell us to be perfectly quiet and watch. Looking back, I think she choosing the stages she took us to with the hope that at least some fragment of the performances of the great performers of the day would stay in our memories. I was about four when I saw Utaemon Nakamura perform Dojoji from the second floor of the Kabuki-za, and I wished the play would never end. Even at that young age I remember feeling an aura around him. Seeing the Kabuki performances of Shoroku Onoe II and Ennosuke Ichikawa and the Noh of the late Hisao Kanze, I am certain that I learned a lot even before I was aware of it.

Since my mother is the one from the main family of a Kabuki hayashi school, I could just as easily have taken that path, but the reason I chose Noh is because I thought my father looked so cool when he was performing on the otsuzumi in the Noh play. When I was little there were only full-sized adult drums, so I used to pretend I was playing the otsuzumi by using my left hand as the drum skin and beating it with my right hand. When I was three, my brothers and I were officially apprenticed under the late Master Tetsunojo Kanze. I was three, my younger brother, now Denzaemon Tanaka, was two and my youngest brother, now Denjiro Tanaka was not yet one. I learned the recitation of the plays and the dance. The roots of my Noh lie in what I learned then.

I said earlier that learning the play recitation (the chorus narration and shite monologue) is how I practice, but actually its 90% recitation and 10% practicing my calls. It is important that you train and engrain your body with the essentials of Noh, which are the words, melody and dance movements of the play, so that becomes part of your subconscious. Your ability to do that determines whether or not you will become successful as a Noh artist. If you can’t move from the subconscious, you probably won’t survive in the world of Noh. - That is truly a case of training a child to excel from the cradle. But you must have wanted to play like other children instead of spending all your time in training.

-

It is true that don’t have any memories of playing like a child when I was in elementary school or middle school. It is a very mundane thing, but I remember having the feeling from my elementary school years that an eldest son like myself had to be prepared to work to support his family should something happen to his father. So I wanted to learn enough to be able to perform on stage so I could start earning money.

When my father was 26 he lost his father, my grandfather, who was a Living National Treasure as an otsuzumi performer. My grandfather collapsed during a performance, and since it was in the first half of the performance, my father replaced him and performed the otsuzumi part for the second half of the play. I heard that story from the time I was in nursery school, and my mother would say, “Hiro, if something ever happens to your father you have to take his place.” That is the attitude I took to my practice and eventually to the stage.

We call it hataraki (to serve a master) in the Noh world, that an apprentice should carry his master’s bags and help him backstage, preparing his kimono and his instruments. In my case, my Master happened to be my father and I was doing the hataraki of an apprentice, following him every weekend from the around the time I was a third grader in elementary school. When I could, I went in the evenings on the weekdays as well. While doing my duties as an apprentice in the dressing room, my hataraki , I learned where I should stay in the confined spaces so as not to be in the way, the rules of behavior of the dressing room, how to heat (dry) the otsuzumi skins.

When I was working in the dressing room, I wasn’t just doing my chores. I was watched and listening to a lot of Noh plays. While my Master was performing I sat behind him and listened to the plays. This is what is known as koken (tutelage). If my father was playing a dozen or so Noh plays a month, I was determined to memorize at least one or two of them and to sit behind and play them. In that way I could learn about 12 plays a year. When I finished school in the afternoon I would come home and my father would say to me before dinner, “30 minutes of practice!” And during those 30 minutes I would give it everything. From my mother I learned about the etiquette and the proper attitude towards Noh performance. From my father I learned the techniques of Noh performance, and from the late Master Tetsunojo I learned about the severity and difficulty, and also the joy of Noh, I feel. - What were your middle school and high school years like?

-

From my third year of middle school I was performing on stage in an increasing number of performances and by my first year of high school I think was performing about 20 stages a year. That was a lot for my age, but in my second year of high school that number had grown to 100 stages a year, and by my third year it was 120 stages. And it is a different play every time, so it was quite a task. So with the Noh performances alone there were 120 a year and then there were dances that I also played hayashi for. It was around this time that I felt that I could take over the responsibility of performing a stage if something happened to my father.

After that I went to the National University of Fine Arts and Music, Tokyo, where I was exposed to other types of music, from opera to musicals. And, I believe that it was a very good experience for me to meet others my same age who were devoting themselves to the other traditional Japanese arts of nagauta recitation, sokyoku (Japanese harp music) and shakuhachi flute and nihon buyo (Japanese traditional dance). Seeing and listening to what they did and what they thought, was able to look at Noh more objectively and I was able to ask what it was necessary for Noh to do and what wasn’t. For example, the Noh play Ataka and the Kabuki play Kanjincho treat the same subject, but I honestly think Kanjincho is more interesting. Basically, when it comes to dramatic plays, Kabuki is more interesting than Noh. In historical terms, the more dramatic Noh plays like Ataka and Funa Benkei were written after the audience got a bit tired of the original yugen (ethereal) plays written by Zeami. In other words, in response to the changing tastes of the audience we see the emergence of Noh plays that were more enjoyable to listen to from the middle and later Muromachi Period (1336-1573). So I realized that in order for Noh to survive, we should not be doing the kinds of plays that Kabuki does better. I believe that should be doing plays like Takasago that bring out Noh’s strengths, or Izutu or Teika with dramatic scenario of human inner mind are unique to Noh and only Noh can give full expression to. - I am surprised to hear you say that Kabuki is more interesting [for some plays]. In most cases Noh is referred to as the original [and Kabuki an outgrowth].

-

That is one of the things I don’t like about the Noh world. It is as if they are saying that we[Noh] are the pure bloodline of the performing arts. Even though our teachers and the masters of the previous generation reconstructed the Japanese traditional arts and culture after World War II, there are some who want to preach that Noh is Noh [as if it is an distinct, unchanging and sacred tradition], Kabuki is Kabuki and

Bunraku

is Bunraku. That is what I don’t like. But, in fact Noh is a tradition that adopted elements from

Gagaku

(traditional Japanese court music) and

Kagura

(Shinto ritual dance and music) as well as the

Kowakamai

dance theater popular in the Muromachi period and mystical ritual dance traditions like

Dengaku

in Heian Period (794-1185). So, I feel that Noh is actually an art that has borrowed and copied from other traditions. It may sound as if I am quoting Zeami’s phrase

Riken no ken

(looking at oneself from an objective viewpoint), but I believe we have to look at the Noh world more objectively today.

Fortunately, my blood consists of half Noh and half Kabuki, and to take advantage of the fact that my brothers and I were born with half the blood flowing in our veins coming from a Kabuki family and the other half from a Noh family we started our “Sankyokai” performances to try to create works that brought together the good aspects of both the Noh and Kabuki traditions. Since in daily life the three of us don’t usually talk in any depth about our performing, it was only after beginning to work together on the Sankyokai performances that we began to talk in depth about our arts. And what we found was that neither Noh nor Kabuki is an art that copies others. Rather, they are two arts that approach the same subjects with different values and different viewpoints. - For the younger audience, Noh can be quite slow in tempo and even a little uncomfortable to watch. What do you think can be done to win over the audience of your generation? It seems to me that one of your attempts to do this is the group “Noh in the Present Tense” that you formed in collaboration with the Kyogen master Mansai Nomura and the hayashi flute master Yukihiro Isso in 2006. It appears to be a fresh new movement in which you choose a new shite each time to perform the main role.

-

To be able to perform with an impeccable cast of players, the result should be performances that will be appreciated by anyone. This is a fundamental, I believe. And, although it may not be something for me to say, it certainly helps the beauty of the Noh if the performers are good-looking (laughs).

Also. A lot can be done with the performance format, I believe. We can set a later starting time, such as 8:00 in the evening to make it night theater, and I believe that we can also have a run of performances for a week or so rather than the usual one-off performance of Noh. However, I don’t know if the Noh actor can accommodate this, considering the tradition that Noh is only performed in single, one-off performances and never in runs of daily performances.

“Noh in the Present Tense” began as a project of Hashi no Kai and the concept was to have a performance by three performers of the same generation with sufficient draw to gather audiences to fill the 600 or 700 seat Noh theaters. In terms of contents, what we are doing is rather unique. It is a rather unfortunate fact that we three are the only Noh/Kyogen performers of our generation with the draw to gather audiences of this size, not to mention the technical prowess. I would like to see the younger generation following suit, but in reality it is difficult under the present conditions. So I am working to raise the next generation of talented young shite. If we don’t have star shite like Zeami was in the Muromachi Period, there will be no development for Noh in the future. Because the shite is the center of the Noh world. - What are your thoughts about the potential of the otsuzumi as an instrument? Some performers are trying things like performing with other artists of other ethnic instruments. How about you?

-

I’m not interested in that kind of thing at all. As long as I call myself a Noh otsuzumi artist, I can’t even think of doing solo performances. I believe that the way of the hayashi artist is to perform in the organic dynamic of the trio with a flute and kotsuzumi or the quartet with the taiko drum. For the otsuzumi performer to go off by himself and do sessions with artists from other genre and searching for new potential there is off the mark and a big mistake.

However, I did do the music alone on the otsuzumi for the 2006 production of Atsushi—Sangetsuki, Meijinden put together and directed by Mansai Nomura at the Setagaya public theatre. The otsuzumi is an instrument that is also performed with words (recitation) and that is why I was able to feel purpose in doing the music for that production. And it is because of that vocal element that I have also done performances in a storytelling recitation [ rodoku ]. I found performing on otsuzumi with a storyteller very difficult but I learned a lot from it, trying to be conscious to strike the drum during the intervals between the storyteller’s lines and to use my voice at a volume that wouldn’t drown out the narrator.

My feeling is that whatever work I do, I want it to continue to be within the context of theater music, or music within the whole of the theater performance. I want to believe that if I continue my daily practicing my music will continue to mature as an art. My aim in art performing and the way I use my body is to be as free as possible and, as we say, “Cross the Heavens and Earth.” - You also compose (write) new works of Noh.

-

Composing a work of Noh is called

sakucho

. Sakucho means to create a tune [melody]. I have done it 20 some works now. There have been some meaningful results like shite Rokuro Umewaka’s

Kukai

and composer Jyakucho Setouchi’s

Yume no Ukibashi

and

Kuchinawa

, but what I have learned is that it is very difficult to create new works of Noh.

In Noh there are limitations in terms of the movements and music and the potential for what we call [psychological/philosophical] “expansiveness.” It is difficult to use devices like stage mechanisms and choreography to enhance and expand it like you can in Kabuki. And, so it is very difficult to bring in contemporary subject matter. However, I felt that if you pursue themes daily life that were the same in the Muromachi Period as they are in today’s Heisei (1989-present) world, such as Jyakucho’s eroticism, there are possibilities.

And, I believe that it is best to do it with the same composition methods and the same choreography methods as 600 years ago. I am being asked to create a new work for Noh in the Present Tense, but for the time being I want to see the three of us doing good productions of the famous old works from the Noh repertoire for the audience before I try new works. Within ten years or so I should be able to have something new to show. - I look forward very much to that. Do the three of you in Noh in the Present Tense have any plans to do overseas performances? Since you stand out so prominently in today’s scene, and are visually a very pleasing group to watch, I’m sure that you could bring fresh, young and interesting Noh to foreign audiences.

- I would like to do that. But since we have a schedule that is full for the next two years and all of us are busy, it would be three or four years before such performances could be realized even if we started planning right now. But I definitely want to bring charm of our young Noh to world audiences.

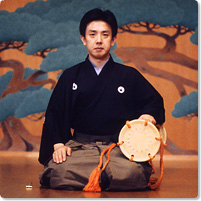

Hirotada Kamei

Looking to the future of Noh with Hirotada Kamei, an Otsuzumi (Okawa) artist who calls himself a Noh actor

Hirotada Kamei

Born in 1974, Hirotada Kamei is the first son of Tadao Kamei, Noh otsuzumi master of the Kadono school, and his wife, Sataro Tanaka, the 12th-generation head of the Tanaka school of Kabuki and Nagauta hayashikata . After his first performance on the Noh stage in 1982 in the play Kappo , he performed not only hayashi but child roles in a number of plays. Until now he has performed otsuzumi in numerous Noh plays including Ishibashi , Rangyoku , Okina , Dojoji , Sagi , Sotoba komachi , Tokusa and Higaki . He has participated in overseas performances in France, Germany, Ireland, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, India, China, Hong Kong, South Korea and the countries of Africa as well. He has also composed numerous new Noh plays and revivals of old plays. In 2003, he was awarded the Encouragement Prize of the 18th Victor Traditional Arts Promotion Foundation Awards, and in 2007 he received the 14th Japanese Traditional Cultural Contribution Award. He is the leader of the “Sankyokai,” “Keikokai” and the “Hirotada no Kai.” He also serves as an instructor at the National Noh Theatre and the National Theatre’s training programs.

Interviewer: Kazumi Narabe

Photo: Ken Yoshikoshi

3rd “Name of Kai: Kamei Hirotada”

(Dec 2004 at Hosho Nohgakudo)

Photo: Maejima Photo Studio