- I believe that you must be the first artist from the traditional arts to become artistic director of a public theater. What has been the reaction of the people around you?

- Concerning my relationship with the Setagaya Public Theatre, it is a theater that has held Kyogen performances and workshops ever since it opened, so they were a familiar theater for me and I also felt an affinity for a lot of the theater’s other programs, so I think there was a mutual familiarity on both sides. Of course there was surely some concern about working with people from a different art world, but I feel that the sense of expectation about what we could do was even greater.

- You are now in your fifth year as artistic director. At the start of your term three official principles of artistic policy were announced, including “Community relevance, Contemporary relevance and Universality,” “Fusion of Traditional and Contemporary Theater” and “Comprehensive performing arts – Total Theater.” Have there been any changes in those principles in the five years since?

-

These were the principles of the Setagaya Public Theatre and also my own personal principles, so nothing has changed regarding them. It is the fate of someone like me born into a traditional arts family to be always concerned with the “Fusion of Traditional and Contemporary Theater,” and I believe that it is also relevant when I think about what it means to be “public” in my role as the artistic director of a public theater. In other words, being public means having both a viewpoint that reflects the contemporary world we live in and being able to reflect a universal viewpoint that transcends the contemporary. And, isn’t this in fact the same attitude that someone involved in the traditional arts must have?

This is the policy I follow in my activities outside of traditional Kyogen performance, and among these, our Machigai no Kyogen (“Kyogen of Errors”) that was based on Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors has been performed not only in Japan but in the U.S. and London. Apparently in London the audiences were a bit shocked to see a Kyogen style production of Shakespeare, but it was very well received in America.

Since I became artistic director at Setagaya Public Theatre, we have done a production titled Atsushi – Sangetsuki Meijin-den using only Kyogen actors which is based on novels by Atsushi Nakajima and adapted to include elements of the world of the author’s novels set against a backdrop of his life. And, in our current production of Kuninusubito , which is an adaptation of Richard III , I have used not only Kyogen actors but also Japanese New Theater actors like Kayoko Shiraishi and a variety of other actors and performers known for their different physical styles of acting.

Actually, we have been making changes continuously in the production since it opened. I play Richard III, named Akusaburo in the Japanese adaptation, and I also direct the play, which means that it is taking some time for me to be able to see the play from the audience perspective. This is because in Kyogen there is no director and the performing style is one in which you face the audience and communicate with them to shape your performance and staging, and I wanted to use that style of actor-audience relationship in this production of Kuninusubito . When creating a theater work, it can be very important to have the ability to work impulsively and intuitively, but at the same time I feel that it is necessary to have the time to let it mature through interaction with the audience. - Your Machigai no Kyogen that premiered six years ago and the current Kuninusubito are both based on Shakespeare plays. Is there something in you that is drawing closer to Shakespeare or are you drawing Shakespeare into Kyogen theater? Also, I would like to know if you feel any difference between your approach six years ago and today.

-

I would like to think that I am getting closer to Shakespeare. When I did

Machigai no Kyogen

it was an experiment and I didn’t know at first how well Shakespeare and Kyogen would go together. We did it only with Kyogen actors and I staged it in the way it would be approach from a Kyogen standpoint, but I didn’t know at first if it was successful from a Shakespeare standpoint until I began looking at it from that perspective and got the feeling that I was getting closer to Shakespeare.

In the case of Kuninusubito , I was looking at Shakespeare not only from the standpoint of Kyogen but also through a variety of other filters. I believe that the result involved a birth of such originality that you can’t really say what the prime perspective or style is. Since it is being directed by myself, as a Kyogen artist, there are certainly elements that represent a Kyogen approach to a Shakespeare work, but as I mentioned earlier, the roles of Ms. Shiraishi and a variety of veteran New Theater and Small Theater actors as well as young actors and even performers, all with different styles, and the fact that we use Kabuki musical accompaniment, I believe this has a production that transcends all former categories to become a completely new work.

However, due to that very fact, it is hard to decide what context to fit it in, what the X and Y axes are. I guess I just have to believe that it is all within myself (laughs). Of course, when I did [ Machigai no Kyogen ] as a Kyogen production, I think everyone expected that they had to do it as Kyogen, but this time that was not the case, as I sent it out on all kinds of vectors and finally we seemed to come up with X and Y axes that everyone could share. - What was the most important thing you focused on in order to create that common context that all the actors could share?

-

They say that

Richard III

is a brutally tragic play, but as I read it, I didn’t feel that. There is a lot of play on words and there are funny situations in it, so I don’t understand why the British can’t laugh at them. According to the Shakespeare scholar Shoichiro Kawai who did the Japanese adaptation into

Kuninusubito

for us, the final monologue in

Richard III

is written with a consciousness of the post-Renaissance “modern self,” which made me think that such an interpretation is a factor along with the “realism” and furthermore the “naturalism” of British theatre that keeps the British from finding laughter in

Richard III

.

So, I decided to approach this odd side of Richard III using the traditional Japanese situation-comedy theater form of Kyogen. However, I knew that only accentuating the funny side of the play, people would come away with little more than a feeling, “That was fun.” So, in order to have contemporary actors perform this play you have to delve deeply into the characters’ souls (psychological development), but if you pursue this aspect too much you run the risk of causing the opposite reaction of “How dark, heavy and cruel.” A performance like that leaves no space for audience to enter the play and it will not be interesting for them at all. So, I believe that you have to first of all create scenes where you can interact and communicate with the audience and then bring in the modern self to deepen the play in ways that the comedy cannot and achieve a good balance of the two. - One of the key roles in that production was Kayoko Shiraishi, who acts the parts of all of the four women who are involved with Akusaburo (Richard III) in the play. Where did this idea come from?

-

The late Yasunari Takahashi, who wrote Machigai no Kyogen for us once said that in the future, if we do

Richard III

, something will have to be done with the women’s roles. So, I talked with Mr. Kawai about what we should do with the women’s roles. I have always thought that the female characters in Shakespeare’s play are weaker in terms of character development than the males and that they leave less of an impression at first reading. For example, the character Anne, who eventually marries Richard, the man who killed her husband, is a character embodying innocence. However, seen from another perspective, doesn’t she do this because that is the only way for her to live, which is in fact makes her a symbol of the weak social status of women and their hopelessness? That may be why they become the sad victims of Akusaburo tossed on the waves of fortune.

So, as Shakespeare himself may be suggesting, we decided to reverse things and make all four women a single character in effect by having one actress do all four parts. In this way, we had them stand opposite Akusaburo as a form of conglomerate “woman figure.” And, that decided, I felt that only Kayoko Shiraishi, who is a veteran, powerful actress, could play that role. However, as the one playing Akusaburo, I can tell you that it was very exhausting. I couldn’t let down my guard for a moment, and it took a lot of strength to try to win her over (laughs). - The scene where Akusaburo (Richard III) and Anne meet for the first time was very interesting.

-

I didn’t really expect the audience to laugh that much. I thought that was a place where we didn’t want to show pity for Anne, who had suffered the loss of her husband (Edward) and her father-in-law (Henry VI), both killed by Richard. In the original Shakespeare, this is a scene where the grieving Anne comes out walking behind her father-in-law’s coffin and rebukes Richard. I believe that is meant to express her distress and grief at having lost her social status, but that is something that is difficult to understand in the modern context. So we changed to a scene where it is her husband’s coffin that is brought out and have Anne grieving her lost husband.

Anne was still in her teens when she was married and still knows little of the world, and although she is still young with her life to lead, she is already a widow. So I wanted to make it a situation where she is being asked to choose between her now dead and mute husband and the persuasive Akusaburo. That is why the scene is staged as it was and I believe that communicated well to the audience. - The set was similar to a Noh theater stage. Was that something that you insisted on?

-

No. That was the idea of the stage designer. Because this is a play where a lot of different set requirements are necessary for each scene, so I asked that the set be a simple one of an abstract nature.

Since Shakespeare’s plays were originally performed in the Globe Theatre with its round empty stage resembling a town square, I thought it would be best to stage this play with a simple, abstract sort of stage space. I believe that one of the reasons Shakespeare and Noh-Kyogen go so well together is that the stage space of the Globe and the Noh stage are quite similar. When we performed Machigai no Kyogen at the Globe Theatre in London, I remember feeling that we, who were used to performing on the Noh stage and know how to use it so well, knew the structure of the naked stage space more thoroughly than the British theater staff, and I felt that our methods were better suited to performing on that type of naked stage. - Watching Kuninusubito , I felt that there were many parts where you used traditional methods. And when I say the traditional I mean not only the Kyogen art that is your field but also, for example the scene where the war banners are brought out, which reminded me of classical Chinese Opera, and I also felt something of the style of the traditional Italian mask comedy theater, Commedia dell’Arte, in the style of entrances and exits.

- I am very glad that you saw it that way. We also used Kabuki musical accompaniment ( hayashi ) and elements of ancient Japanese gagaku music, and for the shadow figure I used a Kabuki kuroko wearing a Commedia dell’Arte mask. Although there wasn’t much of it this time, I often use the silhouette play technique in my staging, and it may have the appearance of Wayang Kulit.

- In other words, when you speak of a “Fusion of the Traditional and the Contemporary” your “traditional” doesn’t mean only Kyogen?

-

When I did

Horazamurai

(based on

The Merry Wives of Windsor

) in 1991 and

Machigai no Kyogen

in 2001, they were trial-and-error attempts to see how close Shakespeare and Kyogen could come to each other as a “Fusion of Kyogen and Shakespeare.”

However, Kuninusubito is approached in a completely different way. I am including not only Kyogen and other Japanese traditional theater arts but also the essences of a variety of different performing arts. When it comes to a difficult play like Richard III , I have to think of a wider range of effective methods than those provided only by Kyogen. Down to the smallest folding fan, I think about and use anything that I find effective, and even among the Japanese traditional tools, I may have a [horizontal] bamboo flute used like a [vertical] shakuhachi flute and have it played in a gagaku style. I believe that we have to use everything within our means in the broadest, most expressive ways possible. And isn’t that really the essence of modern Japan? - Concerning the music, I wondered why you didn’t use the 4-instrument Noh style from the beginning.

-

As the late Yasunari Takahashi said, I believe that if you take the large tree of Shakespeare as a premise and then take the small receptacle of Kyogen and fill it artfully like a Japanese bonsai potted tree, it will be successful for achieving a Kyogen-like aesthetic. In the case of Machigai no

Kyogen

, I feel that we were successful in fitting the bonsai nicely into the potting tray of Kyogen.

However, with Richard III you have a difficult work that is hard to grasp completely, even in the original, and even people who know the historical premise of the War of the Roses will have a hard time fitting it all into the container. So, if you cut the script back and abstract the essence and force it into the 4-beat style of Noh, it would certainly take much of the interest out of the complex and, in a sense, aggressively meaningful Shakespeare original.

In short, if you were to try to make a modern Noh play (new work) out of Richard III , you would have the ghost of Richard coming out on stage and reciting a history of who he had killed and who those people had killed and then be consumed by the fires of Hell. That wouldn’t be doing justice to the full material of Richard III . That is why I wanted to take it out of the framework of Noh-Kyogen and make full use of the techniques of larger theater traditions that many more people are familiar with, including Kabuki, Commedia dell’Arte and classical Chinese Opera, in order to create a play with a different flavor from anything done before. That is because Shakespeare is so large and vociferous and full of meaning. - It sounds like you used all of your theatrical experience until now and virtually put all your cards on the table at once (laughs).

- That’s right. I have been told it was like having the entire toy box dumped out on the floor (laughs).

- In the traditional performing arts there is much importance placed what we call ichigo-ichie in Japanese, the importance of each performance as a unique encounter that will never happen again, in other words, the precious value of each moment. But in the modern theater world, the same actor is performing the same role every day at the same time, which is far from the traditional ichigo-ichie ideal. How do you personally resolve this difference?

- In the traditional performing arts you have highly refined forms, or conventions, and by focusing your technique and your concentration on that form, you create the character. In the case of a new work, however, the refining process only starts from the first performance, and I believe that it will take some time for the roles to become refined. With a new work the forms have not yet been established, so there is bound to be some doubt and some discomfort as the actors try style A, style B and style C for acting out a character’s role and decide where to place emphasis. Right now we are still in that stage of seeking out our style and developing our characters.

- And at the same time, the new work itself is also refined (matures).

- That’s true. So, I have to build the framework that will shape this into the kind of play I am aiming at. If you create the framework from the beginning based on preconceptions you may have and try to fit the actors into that framework, it becomes difficult and confining for the actors. That is the kind of situation that creates a play with no “expansiveness” in terms of what the audience experience and fails to develop the kind of intellectual stimulation a play should have. On the other hand, when the framework is too loose, you can’t find the framework within which the other actors are working and thus you can’t see the desired points of contact. That makes it difficult for the actors to enjoy the play. We are still at the stage where we have to keep things open, but gradually we have to strengthen the framework by finding out where the loose points are.

- It is said that you want to create a new form of Japanese performing art through a fusion of the traditional performing arts and contemporary theater. At this point in your efforts, what kind of new Japanese performing art do you envision?

- Up until now I have proposed a concept of Japanese theater in a total, inclusive sense. With Kuninusubito this time, although this is just a beginning, I believe that I have put forward one such new form of theater. From now on I intend to work with an approach that is not restricted to the knowledge or methods of the Japanese traditional performing arts. For example, with regards to masks, I won’t say that Noh and Kyogen masks are the only type of mask I use, rather I will try to create new masks, perhaps by borrowing ideas from Commedia dell’Arte masks. You might say that it is like mixing soy sauce and mayonnaise to get a new flavor.

- When speaking of a new form of “total theater” that draws from traditional Japanese performing arts, there are foreign precedents in France’s Theatre D’Soleil and in and Peter Brooke.

-

A friend of mine said that they are criticized as “fake Japon” locally (laughs). But I don’t think it is something to be criticized. I myself have been influenced quite a bit by Le Theatre du Soleil and in and Peter Brooke. And now, I would like people like Simon McBurney and Robert Lepage to see

Kunimusubito

and I want to continue to do works that I could show to these people. No matter if people call it fake or whatever, the people who pursue viable ideas with a passion are the winners in the end. Looking at this from another perspective, their actions are proof of the fact that Japan has a very rich tradition in the performing arts that has inspired artists of this level. It is good to see these foreign artists making use of these traditional arts, but at the same time it poses the question, “Why aren’t Japanese artists taking them and bringing them to the world stage?”

We are seeing approaches like that of Kanzaburo Nakamura taking his Kabuki overseas and performing in temporary theater facilities, and I am doing traditional works overseas performances too. But what I would like to do is to test the strength of Noh-Kyogen using the universal platform of Shakespeare. - Does that mean that you always have the international scene in mind when you do a new work?

- Yes. The work Atsushi makes interesting use of a lot of Chinese characters, so I would like to try presenting it in the countries of Asia that use Chinese characters. I would also like people in the West see this work because it contains Chinese character-based culture that could never have developed in an alphabet-based culture.

- Is the “total theater” that Brooke and Le Theatre du Soleil are striving for the same as the one you seek as an artist trained in the Kyogen tradition? Or are they different?

-

From an intellectual/spiritual perspective, I think that we Japanese are better at expressing a world of small containers, smaller situations, rather than larger ones. A small container can still be deep. So, rather than a big container like Shakespeare, we are better at handling smaller containers with tightly knit relationships such as those in my previous work

Atsushi

or the first contemporary theater work I ever directed, Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s

Yabu no Naka

(In a Grove). But these works are heavy in the intellectual/spiritual aspect, so it is hard to make good entertainment of them. That is why I want to seek a kind of “total theater” that expresses the worlds of both large containers and small containers.

And if I were to add something to that, it would be the problem of my identity as one born into a family of Kyogen performers in the present day. I started out from the dilemma of why should I have to be performing Kyogen in the contemporary world and that has led to an ongoing questioning of my raison d’etre . In Machigai no Kyogen there are a pair of twins, and my starting point is the question, “What if there were two of me?” This new work Kuninusubito may be the first work in which I have been able to distance myself from that questions to some extent.

It may seem like a complete reverse of what I was saying earlier, using the methodology of Kyogen, even though it is a tradition far removed from the “modern self” of contemporary theater, turns out to be an opportunity for me to examine the “self.” For example, I think about what the reason is for us to make the effort to go to a theater to see a play. I believe that the theater is a place where we get a shared experience of things that are in the realm of the “public,” but in the end we bring that experience back to our self. So, in this sense the theater is a part of a process of circulation of thought in which we enter things at the public level and then bring them back to the private level and pursue it further to the level of identity. For that reason, I believe that theater should first of all offer an entrance point that everyone can share in, and not be a only a personal experience from the start.

I am not a member of the generation of ideology, so you will probably creating works with an intellectual theme intended to make a social statement. But I hope that back looking into myself and the question of how we perceive ourselves, I can create works that touch the hearts of individuals in a direct and moving way. - On the occasion of my appointment as artistic director, by Mansai Nomura:

-

From

PTex

interview, July 31, 2002 edition

As of this August I will assume the post of artistic director of the Setagaya Public Theatre. While maintaining the best of the accomplishments of this theatre in its five years, I hope that some of my own color will gradually appear in the theatre’s activities.

Noh and Kyogen have a history of flourishing as an art under the auspices and support of the samurai class of the Ashikaga Bakufu government in the Muromachi Period (15th-16th centuries) and, although the scale may be different, isn’t it a similar situation in terms of the public nature and public funding from Setagaya Ward? The wonderful thing is that thanks to this kind of public support it is possible to engage in artistic creative efforts that are not possible for commercial theater with its time and monetary restrictions. However, there are also responsibilities that go along with using public funding. To clarify those responsibilities, I have prepared the following three action policies. - 1. Community relevance, Contemporary relevance and Universality

-

In taking this post, I have chosen the words “I am of this neighborhood” (

Kono Atari no mono de gozaru

) as one of my key phrases. These are the words that a character in a Kyogen play speaks in way of self-introduction when first appearing on stage in a play. By saying, “I am of this neighborhood” instead of using a personal name—like Hamlet for instance—a unique aspect of the tradition is revealed, I believe. Why would a character use such a form of introduction? By speaking these words, the character is telling the audience that he is the same type of person as them and the play they are about to see is based on a world-view similar to theirs. At the same time, it is a phrase that indicates that Kyogen has a universality that speaks to people of all eras in all places.

In choosing these words as my key phrase in my post here at the Setagaya Public Theatre, I want to show that I intend to live as a person of Setagaya and value the views of its citizens. Through workshop activities and institutions of the local society like its schools, I hope to return to the people the identity of Japanese culture that was born of the Kyogen tradition, and through performances I hope to create works with the universality to that will speak to people of the contemporary world, no mater what region or nation they live in. - 2. Fusion of Traditional and Contemporary Theater

-

I come from a traditional performing arts tradition and I naturally want to make use of the ideas and philosophy of the traditional arts. However, that doesn’t mean that I want to color everything with the style and look of the old traditions. I only want to make use of the knowledge and creative thought that has been nurtured in the traditional arts and use it as a source of new ideas.

Noh-Kyogen has recently received designation as a World Heritage by UNESCO. This fact can be interpreted in several ways, but I believe it is a mandate to return the 600-year-old heritage of a sophisticated theater form and its methodologies to contemporary society as a living tradition. Through the creation of new works and workshops, I hope to see contemporary artists make use of the traditional ideas in ways that we learn from one another and discover new possibilities that will lead to the creation of new Japanese performing arts.

For example, from performing with contemporary theater actors, I feel that they are skilled at depiction of story and expressing psychological aspects of characters, but I feel that they are not as skilled at creating “place” and situations. This is only one small example, but I believe that in the rehearsal studio it is possible to convey heritage of Noh-Kyogen to the contemporary performing arts. And just as Yukio Mishima wrote his collection of “Modern Noh Plays,” I want to commission contemporary playwrights to write a collection of “Contemporary Noh Plays” based on works like that. And in the same way I would like to have contemporary directors try creating stage sets that make use of the concepts of the Noh stage. - 3. Comprehensive performing arts – Total Theater

-

I believe that the traditional theater arts of Noh, Kyogen and Kabuki retain a “total-ness” that has been lost from other forms of theater since the modern period. Although there are separate names for the arts of narration (

katari

), dance (

mai

) and chant (

utai

), they are all integrated into one seem-less “total” world of expression in the traditional theater forms.

Although my knowledge is limited, it appears to me that when looking at the contemporary performing arts of Japan and the West as well, the cutting edge arts are increasingly interdisciplinary and hard to categorize. The physical arts of dance, circus, street performance and the arts based on words, including drama, literature and poetry are increasingly combined with media arts bringing together live music and video to create works that cross the conventional boundaries between artistic genre. Good examples of this trend are the works by Peter Brooke and Simon McBurney that have been performed at the Setagaya Public Theatre, as well as numerous contemporary dance works. The production by Robert Lepage scheduled to be performed at the Setagaya Public Theatre this autumn is another leading example of this trend.

It is no coincidence that I, a practitioner of the traditional theater, should be taking the post of artistic director of the Setagaya Public Theatre at a time when such contemporary artistic trends are so strong. It is because I believe that the strength of traditional performing arts, which are originally “total theater” disciplines, is a necessary asset in the work of reuniting today’s contemporary performing arts genre. From now on, as a policy of the theatre, I want to make efforts to revive the skills and wisdom of the performing arts that have become fragmented since the advent of the Modern Era and attempt to reunite them in new forms.

The Setagaya Public Theatre is fortunate to have a large and supportive audience. I want to work hand-in-hand with all of the theater staff to make our theatre one that can set an example for other public theaters and even play a leadership role.

I ask everyone for their ongoing support and encouragement in these efforts.

Mansai Nomura

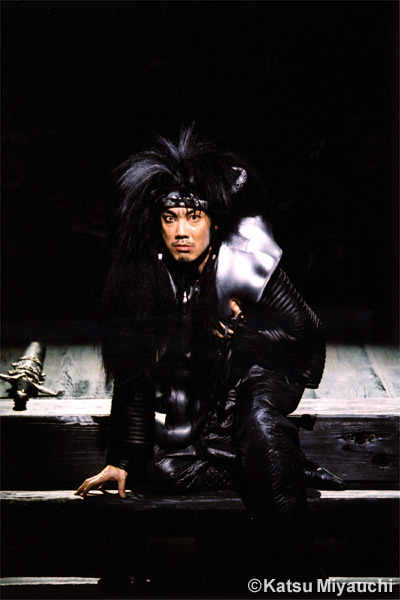

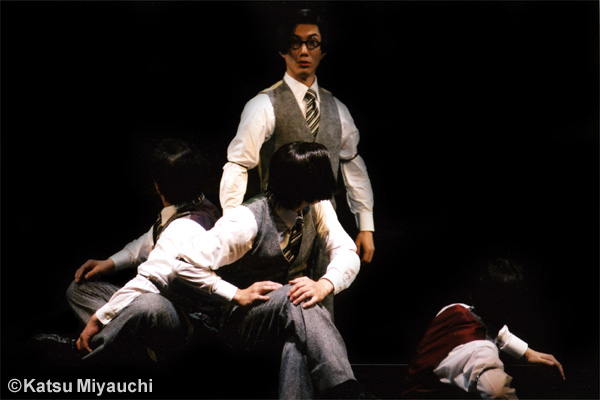

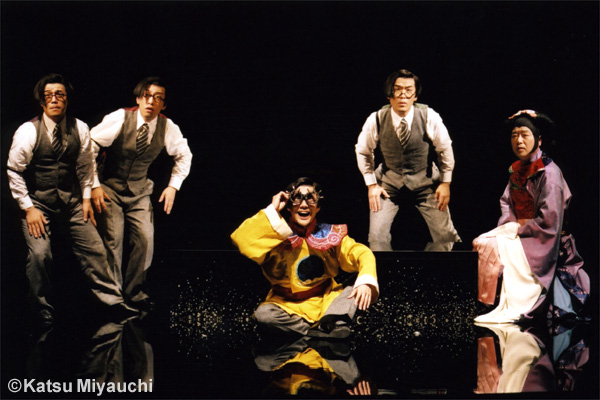

A glimpse of the total theater that Mansai Nomura envisions as a Kyogen actor alive in the contemporary world

Photo: Akihito Abe

Mansai Nomura

Born in 1966, the Kyogen actor Mansai Nomura is a son of the Kyogen actor Mansaku Nomura, who has been designated as Important Living Cultural Entity (“Living National Treasure”) by the Japanese government. He made his stage debut in 1970 with Utsubozaru. In addition to performing with the “Mansaku no Kai” Kyogen company, Mansai has also led the “Gozaru no Kai” since 1987 which presents biannual productions of “more familiar and easier to appreciate Kyogen.” He works to spread the art and appreciation of Kyogen by performing in halls and taking productions to festivals in Japan and overseas. At the same time he has worked to encourage a new fusion of traditional Japanese arts and contemporary theater through direction of highly acclaimed works like Yabu no Naka (In a Grove), Rashomon, Machigai no Kyogen, Atsushi – Sangetsuki, Meijinden and Kuninusubito. In 1994 he studied in the UK as the Agency for Cultural Affairs Overseas Study Program for Artist. As an actor he is active in television dramas, movies and as a stage actor he has performed in Jonathan Kent’s Hamlet and Yukio Ninagawa’s Oedipus Rex. Since 2002 he has served as artistic director of the Setagaya Public Theatre. In 2006 he won the Kinokuniya Drama Award for direction and composition of Atsushi – Sangetsuki, Meijinden. (Updated in June 2025)

(Interviewed by Kazumi Narabe, July 8, 2007)

Kyogen and Hogaku (Japanese traditional music) programs of the Setagaya Public Theatre Founded in 1997 and under the artistic direction of Mansai Nomura since 2002, the Setagaya Public Theatre continues to present a variety of productions with the theme of a fusion of traditional and contemporary Japanese theater.

●“Contemporary Noh Plays Collection” series

The theatre’s “Contemporary Noh Plays Collection” series is the result of a proposal by Mansai Nomura and he serves as supervisor for the series. Series productions until now have included AOI/KOMACHI (written and directed by Takeshi Kawamura) based on the Noh plays Aoinoue and Sotobakomachi , a contemporary version of the Noh play Motomezuka (written and directed by Tatsuo Kaneshita) based on the piece by the Muromachi period (16th century) writer Kan-ami, known for his continued influence on modern literature, and NUE , a contemporary version of the famous Noh play from the Heian Period (written and directed by Akio Miyazawa).

●“Kyogen Theatre”

The theatre also presents a “Kyogen Theatre” series that presents Kyogen plays not as traditional theater but as “performing art” for the contemporary audience in productions performed by Mansaku Nomura and members of the Mansaku no Kai using an innovative Noh stage constructed at the theatre with three hashigakari entrance runways.

●“MANSAI Kaitaishinsho”

This series is one that proposes to search for a new “Japanese theater identity” by dissecting a variety of elements composing today’s world of contemporary art. Mansai Nomura invites guests from a variety of genre for this series to give talks and performances.

● Nohgaku Genzaikei ” (Nohgaku in the Present Tense)

This new series attempts to explore the full possibilities of Nohgaku, Nomura invites leading Noh protagonists with his peers like the Noh flutist Yukihiro Isso and Noh otsuzumi drum performer Hirotada Kamei to tackle the present and future possibility of Noh. By presenting a theater performance in the Setagaya Public Theatre’s specially constructed Noh theater under the title “Nohgaku Genzaikei Theater version@ Setagaya.”

Kuninusubito

Written by Shoichiro Kawai, directed by Mansai Nomura, premiere: 2007

This play is an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Richard III . With the main character, the infamous Akusaburo (=Richard III) (played by Mansai Nomura) who plots murders in order to claim the throne, this play tells of the battles between the White Rose and Red Rose clans during the War of the Roses. Staged in a style different to some degree from Kyogen and cast with contemporary theater actors as well as Kyogen actors, this work represents an attempt to define a new type of contemporary theater.

Photo: Katsu Miyauchi

Horazamurai

Written by Yasunari Takahashi, directed by Mansaku Nomura, premiere: 1991

Based on Shakespeare’s The Merry wives of Windsor and adapted for performance by the Kyogen company Mansaku no Kai as the first play of its creative Kyogen Shakespeare theater project. Performed to acclaim in Japan as well as in London, Hong Kong, Adelaide and other foreign cities.

Machigai no Kyogen

(Kyogen of Errors)

Written by Yasunari Takahashi, directed by Mansai Nomura, premiere: 2001

Based on Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors and adapted for Kyogen performance. Shakespeare’s script was translated into the unique language of Kyogen and set to Kyogen forms of physical expression and performed exclusively by men (Kyogen company Mansaku no Kai). Kyogen masks were used in this comical presentation of the adventures of a pair of twins involved in a mix-up of identities. It was performed in the Globe Theatre of London in 2001 and revived later in numerous overseas performances to high acclaim.

Photo: Jun Ishikawa

Atsushi – Sangetsuki, Meijinden

原作:中島敦

演出:野村萬斎

2005年初演

By Atsushi Nakajima, directed by Mansai Nomura, premiere: 2005

Composed from parts of the two novels Sangetsuki and Meijinden by Atsushi Nakajima (1909-42), this was the first play to be directed by Mansai Nomura after taking the post of artistic director of the Setagaya Public Theatre. This work brought to the stage the richly poetic world created by the use of Chinese-style literature in the novels of Atsushi Nakajima while interspersing elements from the author’s short 33-year life. The staging uses a rich combination of Noh and Kyogen style chant and musical accompaniment. Attention also focused on the performances for some of the brightest young stars of the traditional Japanese music world, Hirotada Kamei on the otsuzumi drum and Dosan Fujiwara on the shakuhachi flute.

Photo: Katsu Miyauchi

Kyogen theatre part II

Kagami-kaja

Photo: Yuu Kamimaki

Kyogen theatre part III

Kusabira

© Setagaya Public Theatre

Kyogen theatre part III

Tsukimi-zato

© Setagaya Public Theatre

Kyogen theatre part III

Akutaro

© Setagaya Public Theatre