- Presently you are engaged in a wide range of work in design, extending well beyond your primary field of costume design. How did you become interested in design in the first place?

- I liked drawing pictures from early in my childhood, but I wasn’t the type who would rather spend all my time alone doing oil paintings and never get a job. At first I wanted to be a manga (comic book) artist and make that my job, but when I was a child there weren’t many information sources like there are today and I didn’t even know the word “design” or that there was such a profession. But it happened that one of my classmates had an older sister who was applying to the design department of an art college and it was she who told me that design was an interesting profession. That was when I first became interested in the idea of becoming a designer.

- Eventually you were accepted to the Design course of the Fine Arts Department of the National University of Fine Arts and Music, Tokyo (Geidai). Could you tell us something of what you learned there?

-

At Geidai they teach you about “artistic expression” in the large sense of the word, but in the case of design, the courses don’t teach you about the “how to” skills of the actual design work. And, looking back, I think it was actually better that way. So, the most important thing I got out of art school may be the friends I made there. The information I got from talking with the people I met there who were my same age but had knowledge and individuality that were new to me was always stimulating and inspiring.

I was in college during the 1980s when pop art was at its peak, the popular artists were Andy Warhol and Lichtenstein and in the movies it was American Graffiti ; American culture was at the forefront and there was an enjoyable atmosphere to so much of what was going on at the time. It seemed like a waste to spend all your time holed up in the classroom in front of a canvas because there were so many new and stimulating things to find if you went out and around the city. That was the kind of era it was, in my opinion. There was an emergence of fashion and designer brands in Japan at the time, whereas before there had only been the Ivy League look or plain clothes. All of a sudden there was a huge variety of design coming out. - At that time, you and several of your Geidai friends formed a creative group called Diamond Mama, didn’t you?

-

That group name was the idea of Katsuhiko Hibino (Kodue Hibino’s partner). We were a group of students who felt that they didn’t fit in the academic environment of university, and were considered a nuisance by the professors (laughs). We held a few group exhibitions but mostly it was just an excuse to get together and talk, and it proved to be a very stimulating environment for me.

That is the way I spent what was a truly enjoyable four undergraduate year. It wasn’t until just before graduation that I was confronted with the harsh realities ahead. As I began to search for a job, I was shocked to realize that in the advertising industry that I wanted to work in there were no companies recruiting people with my background [in design].

Because magazines were the exciting media at that time, I ended up going around to the publishers of some of my favorite magazines. At the time I was really anxious yet and I just had the idea that it would be nice to work for a magazine I liked. Unlike the usual job-hunter, I went around with my portfolio of works and a desire to know how the magazines I like were actually put together, so I was the one who asked the questions and listened to their explanations. - Were you interested in clothes and fashion at that time?

- It wasn’t that clear a thing at that stage. But, as I mentioned earlier, it was a time when the first designer brands were emerging in Japan and there was also the new trend of imported used jeans and other clothes from the U.S., so I had the feeling that interesting things were happening in the fashion and clothing industries. As my graduation project, I had done designs that might be considered patterns for clothing fabrics, but at the time I was only thinking that I would like to work as an illustrator or a magazine layout designer.

- When was it that you actually began to design clothes?

-

In fact, I don’t really recall very clearly when it was. After graduation I would do some costumes when [Katsuhiko] Hibino would mount a performance work, and would help out on the costumes for the theater group Buriki no Jihatsudan, that I came to know from going to theater performances. And, to tell the truth, it had become a job for me before I was really aware of the fact.

In my profile I write that I began working as a costume artist from 1988, but actually that is just the time when I came to accept the fact that that is what I was doing professionally. That year I terminated the illustration and other creative work that I was doing with the intention of concentrating solely on clothes design as my profession. - What made you decide to concentrate solely on clothes design?

-

Stated simply, I thought I had no talent for anything else (laughs). I had not seen anyone else designing clothes like I did, so I sort of had the feeling, “Hey, this could be OK” (laughs). With the other types of work I did there was always some degree of stress involved, but with clothes I felt that I could express my own originality and do the kinds of things I wanted. Although it was work, it was something that I could really enjoy. That was a certainly an important factor.

Also, by taking the job description “costume artist” I felt that I was giving myself the freedom to do really anything that I chose; anything goes. I had been doing stage costumes, but to tell you the truth, with my education in design and my original intentions of working in something related to advertising, I really had no intention of becoming a stage costume designer. - Some of your early representative work was for the covers of the information magazine Travail (a weekly job magazine for women published by Recruit Co. since 1980). The voluminous costumes in pastel colors that you created for the cover models of that magazine were highly acclaimed as one of the most notable developments in the magazine culture of that period. That work for Travail that made the cover models into “living objet ” figures seems to be very different from the theater costumes you designed, considering the fact that “mobility” for acting is the primary functional requirement of stage costumes.

- As creations, the two were fundamentally the same for me. That is why I used to cause the actors a lot of headaches by making costumes that were heavy and hard to move in when I first began doing theater costumes (laughs). The complaints seldom reached my ears but Hideki Noda, the theater person I have worked with longest, couldn’t help by comment a couple of times how hot and hard to move in my costumes were. Hearing that, I promised to try to make them lighter next time, and in that way I gradually learned to make costumes better suited to the stage. If there is any significant difference between the two types of designs it lies in the fact that with stage costumes there is a story and a character involved.

- Hideki Noda is the playwright and director you have done the most work with, since 1990 when you first did the costume designs for the Toho production of [his play] Karasawagi . What is the process like when you work with Noda?

- First, he gives me the script for the play, and I read it several times. But Noda’s plays are so complex that simply reading the script is not enough to fully understand them, so I meet with him and try to get him to explain them. But, he is one who doesn’t really like to explain things and I end up having to fill out the images myself (laughs).

- Does Noda not give you any specific images of what he wants for the costumes?

-

At first he did. For

Karasawagi

I was very nervous because it was my first time working with Noda-san and the play was going to be done at a very big theater, the Nissei Theater, and for a big production company, Toho. So, I was being overly careful to make designs that I thought would be acceptable to everyone. But, when I took my first set of sketches to Noda-san, he looked at them and said, “Kodue-san, these aren’t like you. They are much too ordinary.”

I took another week and redid all the designs and this time he liked them a lot. He told me, “You should always work freely and boldly like this.” The support he gave me with those words is something that I feel very fortunate to have received at that point in my career. Noda-san is a person who is always full of interest for things he sees and he has never given me any instructions or made demands concerning the things I create. Instead, he always thinks of ways to make the best possible use of my designs when staging and directing a work. - You have continued to work with Noda until the present. Have there been any changes in the working process over the years?

- I have changed. And since Noda-san’s plays have also changed, with the themes becoming more straight-forward in terms of the realities they deal with, and thus easier to read, there are an increasing number of cases in his recent works where a certain type of “reality” is necessary in the costumes. While I have felt some pressure stemming from the fact that expressing those realities may not be my strong point, I also feel that I have come to understand Noda-san’s ideas more fully.

- With your costume designs—and not just those done for Noda’s plays—we feel that you bring in creative and formative design elements that transcend the usual aspects of “reality,” such as a character’s life-style, environment or job. Do these elements usually come from interpretation of the play or the director’s staging plans?

- Sometimes the hints that give birth to the creative ideas come from my stock of designs or my imagination and sometimes they come from elements within the play or the director’s image. In the case of Noda plays, there is often no clear period or country where they are set. In that case, I want to create new costumes like nothing people have seen before, and I make dress the actors in costumes that are beautiful and fun for the audience to enjoy.

- Is there a particular element, such as color, form or material that your designs usually originate from?

- It may be that these elements don’t come to mind separately. When I am doing sketches for a costume, the form naturally comes first and then I color it in, but in some cases there is a “key color” that has been decided on prior to the start of the costume design stage. Because I often use unusual materials, some people assume that the designs are material-based. In the world of fashion there are cases where new materials are created from scratch, but in most of my work there is neither the time nor the budget necessary to create new materials, so I go out and search for existing materials that fit the design’s image.

- Besides your work with Noda, you are also known for your creative challenge to design costumes for the Cocoon Kabuki series of new-age Kabuki stage in a regular theater by the director Kazuyoshi Kushida and starring the Kabuki actor Kankuro (now Kanzaburo) Nakamura.

-

I really enjoyed working in Kabuki. I never expected that my Kabuki would fit my style of design so well. I found that my sense of color fit beautifully with Kabuki. You could say that contemporary “reality” is not my strong point, but in Kabuki costume design there is no need for such reality.

But actually, when I was first asked to work on Kabuki costumes I had always thought of my work as avant-garde and basically Western in approach. So, I was asking why they had come to me of all people with this offer to work on Kabuki. But when I actually started working on it, I was surprised to discover just how Japanese I really am. Take the color of the sky for example. It is clearly different in Japan and France, isn’t it? When the two colors are placed side by side the one I choose is the color of the Japanese sky. Working on Kabuki I rediscovered how deeply the Japanese air and light are ingrained in me. - I’m surprised to hear that that is how you felt. I imagined that working with a traditional art like Kabuki would have been very difficult for you.

-

For certain, it was difficult at first. The first time I became involved with Kabuki was as a costume coordinator for

Sannin Kichiza

in 2001, and I started out knowing almost nothing about Kabuki at that time. The professional Kabuki backstage crew must have been thinking, “What is this person doing here in our workplace?” And even an actor like Kankuro, who had done such revolutionary things with Kabuki up until now, was reluctant to change the traditional Kabuki costume.

After that, however, I had the opportunity to design the costumes for Noda-san’s New Kabuki productions at the Kabuki-za theater and such, and I began to enjoy working in Kabuki more and more with each production. It was also a big help that the audiences liked our productions. So, now the Kabuki people are almost too nice to me and I no longer hear the automatic “No” that I used to get when I proposed something new. It is actually a bit disarming (laughs). - There were no “costume artists” before you in Japan, so it is a profession that you have pioneered by yourself.

-

That seems to be the result. What can I say? It seems that my fate is to be in this position where I am asked to do something completely new with each job. It is not as if I was pioneering with an attitude that “I want to try this, and next I want to do that.” It is more a case of my range of work expanding as I was asked to do one new job after another. It is a job where there is no one I can ask advice from and I tread with fear and trembling into each new realm, but I am the type who can’t say “No” when I am asked to do something. I am also the type that forgets all the hard times once the job is over (laughs).

Given this nature, I believe that it is the ongoing jobs that have been extremely important in training me and honing my skills as an artist and a professional. My work with Noda-san has been that kind of ongoing work that has continued for many years now. Other ongoing jobs have been my series of columns for magazines and now my most frequent work with an NHK (national TV station) children’s program. For this program I do not only the costumes but also the artistic planning, and the pace of the production work demands that I apply the ideas that come to mind one after another just to get the work done in time. It is very good training because it demands quality, volume and speed. - Your newest area of work is industrial design. You have just a broad-ranging solo exhibition that includes not only your in costume designs and work for magazines but also examples of your industrial designs for items ranging from handkerchiefs, glasses, tableware and sports wear to furniture designs. How did you become involved in industrial design?

-

From the time I was in high school I had the strong desire to find work where I could use the drawing that I loved so much and also a strong feeling that I didn’t want to create things that weren’t useful. When you think of an artist, there is an image of the freedom to do whatever they please and everything is allowed, but there are a lot of useless “art works” in the world that aren’t even worth having around. I don’t want to create things like that.

So, I think it was natural for me to begin designing everyday items, for which usefulness is a prerequisite and I know would be used. But this again was not a case where I asked to do it. Rather it was the handkerchief company and then others that asked me if I wanted to try doing some designs. I’ve doing handkerchief designs the longest now, since 1993, and I didn’t begin doing furniture design until after the year 2000.

I feel that the drive behind my creative activity is a making my daily life sound and fulfilling. If my life is not right, and that includes the fundamental of daily life like a clean and orderly house and well-prepared meals, it affects my mental equilibrium and can lead to indecisiveness or lack of confidence in my work. It pleases me that I have been given the opportunity to design the things that I use in that important base of daily life.

Now that I think of it, in my third year of college when I had to choose my major I thought that I would like to try interior design and took some related courses. I made some wastebaskets. The other day when I happened to meet an old friend from our Diamond Mama days, she said that she used to be envious of me in those days because I always looked like I was enjoying myself so much. At the time graphic design seemed to be the free medium while industrial design appeared to have more restrictions. But now that I’m doing it, I feel that industrial design is actually the freer of the two.

Actually, the thing I like least about stage costume design is putting them on people. During the costume creation process there is a costume parade where the actors actually try the costumes on and then they give me their opinions sometimes (laughs). Even though it is still in the creation process and the designs are not finished yet. That’s what I don’t like. With product design I can do the whole design process by myself, and that suits me better. - Someone said that many of the artists of your generation from the 1980s create in order to escape from all kinds of existing values and meaning. That is something that is expressed in Noda-san’s plays as well. Do you feel like your visual expression is also part of the “escapist” generation aesthetic?

- “Escapist generation” is indeed an apt expression. It is an expression that really rings true for me. When I think about why I have always worked alone, it is because I don’t want to have to be working with people of the generation before me or the generation after me. I have just had the bid realization that I am part of the uchi Benkei (lion at home, mouse abroad) generation (laughs). If you say that the reason I have been able to work this long with Noda-san and be this influenced is because we are of the same generation, it really hits the mark for me. The word generation has a heavy sound to it, but when I consider the influences and the encounters it has brought my way and how they have made me what I am today, I can’t help but feel very fortunate.

- Finally, I would like to ask you what your “ability to design” is amidst all this crossover of genre that you are actively involved in today?

- I believe that it is simply “believing in yourself.” If I were to lose faith in myself, I wouldn’t be able to design anything. It goes back to what I mentioned earlier about the daily life aspect. I can’t separate work from my lifestyle, from being comfortable in my life, from creating an environment where my partner and I can spend quality time and enjoy ourselves. I believe that that daily-life base is indispensable for the kind of belief in yourself that leads to good work.

Kodue Hibino

Pioneering a new realm of creative design The world of costume artist Kodue Hibino

Kodue Hibino

The costume artist Kodue Hibino was born in Shizuoka Prefecture in 1958. In 1982 she graduated from the Visual Communications course of the Design Department of the Fine Arts School of the National University of Fine Arts and Music, Tokyo. Since her professional debut in 1988, Hibino has continued to created unique costume designs for magazines, posters, TV commercials, theater, dance, ballet and TV with a different sense from usual fashion designers. In 1984 she won the Encouragement Prize of the Japan Graphic Exhibition. In 1989 she won the Annual New Artist Award of the Japan Graphic Exhibition. In 1995 Hibino won the New Artist ward and the Shiseido Encouragement Award of the Mainichi Fashion Grand Prix. In 1997 she changed her artist name from Kodue Naito to Kodue Hibino.

From August to October of 2007 an exhibition of her work titled “Hibino Kodue Works – Tashihiki no Anbai (Balancing Plus and Minus)” at the Contemporary Art Center of the Art Tower Mito. This large-scale exhibition showed a wide range of works from Hibino’s 20-year career as a costume artist and more recent works in furniture and household goods design.

Interviewer: Kumiko Ohori

13rd NODA MAP production

Kiru

(December, 2007 – January, 2008 at Bunkamura Theatre Cocoon)

Written and directed by Hideki Noda

Costume designed by Kodue Hibino

Photo: Masahiko Yako

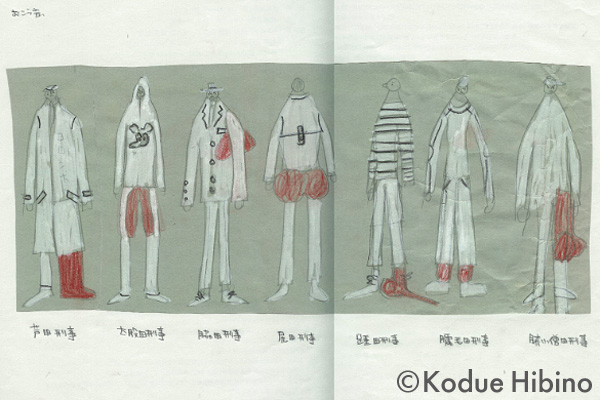

1st NODA MAP production

Kiru

(January – Febrary, 1994 at Bunkamura Theatre Cocoon)

Written and directed by Hideki Noda

Costume designed by Kodue Naito (Hibino’s maiden name)

Photo: Kazunori Ito

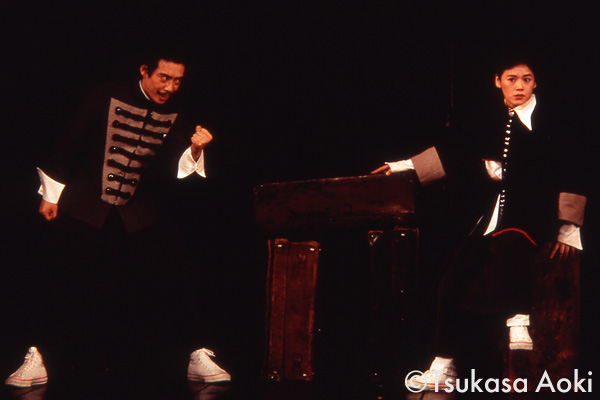

3rd NODA MAP production

TABOO

(April – May, 1996 at Bunkamura Theatre Cocoon)

Written and directed by Hideki Noda

Costume designed by Kodue Naito (Hibino’s maiden name)

Photo: Tsukasa Aoki

NODA MAP extra production

Isao Hasuzume vs Hideki Noda

two-person play

Shi

(December, 1995 at Roppongi Jiyu Gekijo Theatre)

Composition and directed by Hideki Noda

Costume designed by Kodue Naito (Hibino’s maiden name)

Photo: Tadayuki Minamoto

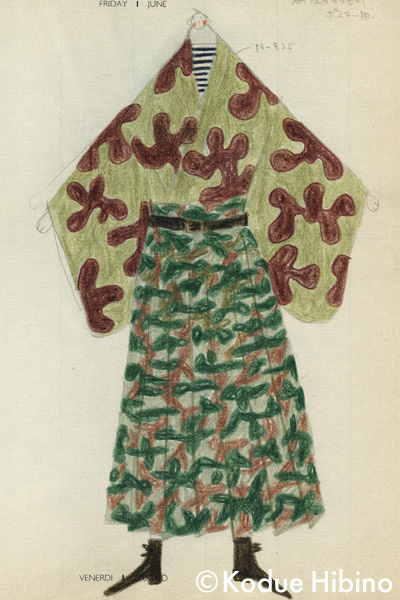

10th NODA MAP production

Hashire Merusu

(December, 2004 – January, 2005 at Bunkamura Theatre Cocoon)

Written and directed by Hideki Noda

Costume designed by Kodue Hibino

Togitatsu no Utare Noda version

(August, 2001 at Kabuki-za)

Written and directed by Hideki Noda

Costume designed by Kodue Hibino

2nd NODA MAP production

“Gansaku” Tsumi to Batsu

(April – May, 1995 at Bunkamura Theatre Cocoon)

Written and directed by Hideki Noda

Costume designed by Kodue Naito (Hibino’s maiden name)

Photo: Tsukasa Aoki

Related Tags