Mansai Nomura

From Boléro to Shakespeare to Manga—The Ever Expanding Potential of Kyogen

Photo: Akihito Abe

Photo: Akihito Abe

Mansai Nomura

Born in 1966, the Kyogen actor Mansai Nomura is a son of the Kyogen actor Mansaku Nomura, who has been designated as Important Living Cultural Entity (“Living National Treasure”) by the Japanese government. He made his stage debut in 1970 with Utsubozaru. In addition to performing with the “Mansaku no Kai” Kyogen company, Mansai has also led the “Gozaru no Kai” since 1987 which presents biannual productions of “more familiar and easier to appreciate Kyogen.” He works to spread the art and appreciation of Kyogen by performing in halls and taking productions to festivals in Japan and overseas. At the same time he has worked to encourage a new fusion of traditional Japanese arts and contemporary theater through direction of highly acclaimed works like Yabu no Naka (In a Grove), Rashomon, Machigai no Kyogen, Atsushi – Sangetsuki, Meijinden and Kuninusubito. In 1994 he studied in the UK as the Agency for Cultural Affairs Overseas Study Program for Artist. As an actor he is active in television dramas, movies and as a stage actor he has performed in Jonathan Kent’s Hamlet and Yukio Ninagawa’s Oedipus Rex. Since 2002 he has served as artistic director of the Setagaya Public Theatre. In 2006 he won the Kinokuniya Drama Award for direction and composition of Atsushi – Sangetsuki, Meijinden. (Updated in June 2025)

An inheritor of the Kyogen tradition established in the 15th century, Mansai Nomura is a director, actor, and dancer who also creates contemporary theater. Situating the performing arts within a vast period ranging from the Middle Ages to today, he constructs works based on the method of Kyogen across all kinds of genres including opera, ballet, Shakespearean theater, manga, and anime. Under the tutelage of his father and master Mansaku Nomura, Mansai has honed his talent and skills by embarking on numerous challenges that testify to his expansive perspective and further crystalize the purity of Kyogen as an artform. Starting with Sanbaso, the Nomura family’s heirloom, we delve into the essence of Kyogen, unique among the performing arts, and also explore Mansai’s style, which activates its astonishing adaptability.

Interview/text: Ayako Takahashi

English Translation: Hibiki Mizuno, Lillian Canright (Art Translators Collective)

The oldest Noh piece in contemporary repertoire, Okina is referred to as “a Noh play and not a Noh play”: it is performed as a Shinto ritual to pray for national and global peace and security. The role of Sanbaso1 is performed by a Kyogen actor, and you have become synonymous with it, presenting it at the 65th Shiki-Noh in February 2025. In the past, Okina performers would go into bekka for some time, a period of purification during which one adheres to various rules, such as cooking with sacred fire, and avoiding women and the consumption of four-legged animals.- In today’s world, bekka is anachronistic, and it’s something I hesitate to mention from a gender standpoint. However, given that it has been a sacred ritual performed by men, I think the intention was for the performer to maintain a sense of rigidity by adhering to certain restrictions that would, in a sense, put a shackle on them. It’s difficult to follow the exact same things today, but I was conscious of the fact that I was preparing for an official Noh performance for the ceremonial Shiki-Noh. So during the month of February 2025, I did abstain from eating breakfast and took cold showers in lieu of ablutions.

-

The 65th Shiki-Noh Okina (2025), Sanbaso (Mansai) Photo: The Nohgaku Performers’ Association

- Your performance of Sanbaso is unparalleled in its exhilarating energy. In both your work in February and in Noh Performance 2020: Prayer for the End of COVID-19 Pandemic, which was presented after the stay-at-home requests were lifted as the first Noh show in a while for both the performers and audience members, I felt that you delivered a passionate, fierce, and fiery performance of Sanbaso.

- I do think that, at the time, I was standing on stage with an almost menacing kind of energy. Logically speaking, there’s no way I can fight against the coronavirus on my own, but in Okina, you transform into deities by wearing masks, whether it’s Okina or Sanbaso. It might be difficult to understand this within a Western context, but basically the ritual occurs by offering your body to the deities as yorishiro, or a vessel, to receive something, and then also by the audience responding in turn to your performance.

Okina is a complex piece, in which the shite (protagonist) is an old man, but also possibly a fetus. Imagine the fetus’ universe as its existence inside the mother’s body—it’s simultaneously within that universe, and also exists as the old man, Okina. The shite is simply alone in the universe, and performs prayers toward heaven and earth, or things like the three elements of fire, water, and earth. When I shared the stage as Sanbaso with Manzaburo Umewaka III2 as Okina, I saw how he was confronting heaven, earth, and humankind while truly feeling the solitude of the universe, and I felt inspired by his interpretation.

The way I perform Sanbaso is influenced by Okina and the other performers, as well as societal changes. When we presented Futari Sanbaso at the Ishikawa Ongakudo in Kanazawa in January 2025, it was my first time performing it after the Noto Peninsula Earthquake,3 so I approached the stage with the hopes of providing some sense of alleviation and relief.

- Could you tell us what Sanbaso means to you in the first place?

- It’s the piece that made me decide to become a Kyogen performer. I was heavily influenced by my father, Mansaku Nomura, and his extremely powerful Sanbaso, and since I performed it as a teenager, a part of me was also carried away by my youthful impulses [laughs]. I was in high school during the era of superstar dancers—obviously there was Michael Jackson, and it was also a time when films by Antonio Gades and Mikhail Baryshnikov were popular. I admired these people, and started to feel like I wanted to get to their level and even go further. As a Kyogen performer, I felt that Sanbaso was the only way I could challenge myself to that extent. Other Kyogen pieces are a bit more realist, and, in a sense—to use an English word—they have some “funny” aspects to them. Although Sanbaso also contains funny elements, the dance can be performed in a sleek or beautiful manner, or in a raw yet refined way.

In 2018, as part of the arts and culture event Japonismes 2018: les âmes en résonance, my father, who was 87 at the time, myself at 52, and my 18-year-old son (Yuki Nomura)—so spanning three generations—we each took turns performing Sanbaso for the day at the Théâtre de la Ville in Paris. My son had just gone through “hiraki”,4 which is to perform one’s first shite role for a major Noh piece. So he was still in the process of training his body, like an innocent Bambi. Last year, my father delivered his final performance, or fumiosame, marking the 90th anniversary of his artistic career. His mai (dance) had become more that of an older man facing the inevitability of human withering, and perhaps more realistic in that sense.

-

The 102nd Nomura Kyogenza: Awataguchi (2023) — Mansaku (center), age 91, and Mansai, age 57. Photo: Shinji Masakawa

- Do you also feel that your Sanbaso has changed as you have continued to perform it?

- At first, I was merely exerting my physical energy, just following what I had learned, but in my twenties, I aimed to deliver an impeccable performance by channeling the militancy of the aforementioned Antonio Gades, and I feel like I maintained that mentality until my forties. From around my thirties, I also began to focus on powerfully emanating a sense of vitality when ringing the suzu bell, perhaps because of my experience starring in the film Onmyoji.5 I was also increasingly becoming aware of things like the presence of deities in all cardinal points or casting a sacred kekkai barrier. When we take the movement of stomping on soil, for example, it connotes stepping on the seeds and breaking ground, but in reality, many things lay dormant beneath the earth, so I also felt this strong sense of violence, thinking about whether I’m awakening these things or actually preventing them from coming out by hardening the ground.

I also had a period where I was resistant to the idea that this dance was rooted in harvest rituals, feeling like we wouldn’t be able to keep up with the global dance scene if we continued to do such rustic things. I do think that my father refined his performance of Sanbaso through his long-term stays in countries like France and the US, perhaps by questioning the way the piece is portrayed from an international perspective. However, I’ve been able to loosen up a bit more in my fifties, and now I feel more open to portraying a calm and peaceful scenery.

- In 2011, you presented the premiere of MANSAI Bolero, a piece that combines the techniques of Kyogen—particularly the performance of Sanbaso—with Ravel’s ballet score. This was at the Setagaya Public Theater when you were serving as its artistic director, and you have continued since then to stage this work in various places. In March 2025, you also performed alongside professional figure skater Yuzuru Hanyu in Mansai Bolero x Notte Stellata as part of Yuzuru Hanyu Notte Stellata 2025.

- My father had always spoken about the similarities between Sanbaso and Maurice Béjart’s choreography of Boléro, so I was very conscious of Sanbaso when staging MANSAI Bolero as well. Although Sanbaso originated as a way of praying for gokoku hojo, or bountiful harvests, given that the performance took place immediately after the Great East Japan Earthquake,6 we decided to imbue MANSAI Bolero with a sense of “rebirth”.Taking inspiration from the opening scene in Shinobu Orikuchi’s The Book of the Dead, where Prince Otsu comes back to life with the sound of water drops (shita, shita, shita), I had decided to represent the state of being transported to a different stage—not through death but via rebirth—by creating a white-out effect, using white lights to momentarily make the stage invisible and reveal its afterimage.

At the same time, I consider Sanbaso to be the same as Uzume’s dance7 from the myth of Amano-Iwato, which marked the beginning of kagura ritual dancing—that is, it takes place during an eclipse. In this way, I wanted to express the four seasons of life by connecting the hours of the eclipse with one’s lifetime as a Japanese person, someone who experiences the seasons in daily life. The cycle begins with winter, then the ice melts and turns into water, plants germinate and come to life in the spring, gradually flourishing and blossoming, then comes the rainy season, summer, storms, and then, once the fruits ripen in the fall, we enter a different world by going into winter again. The gokoku hojo in Sanbaso is the same in the sense that it brings seeds, which are in a state of suspended animation, back to life. We created the performance by incorporating these concepts, as well as aspects of Okina and Senzai from Okina, with the music of Bolero.

-

MANSAI Bolero (2011) Photo: Shinji Masakawa

-

Final scene of MANSAI Bolero (2017, Setagaya Public Theatre 20th Anniversary) Photo: Shinji Hosono

- Whether it’s an awareness toward the international scene or Mei-no-Kai,8 which aimed to highlight the universality of Noh as a form of theater and promote collaborations with other genres, I can see how Mansaku Nomura paved the way for the work you do today.

- Performing across the world is a tradition of the Nomura family. For the Japan Festival held in the UK in 1991, we performed Horazamurai (The Braggart Samurai), a new Kyogen piece based on Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor that was written by the prominent Shakespeare scholar Yasunari Takahashi and directed by my father. I saw how much the British audience enjoyed and resonated with the piece because it was Shakespeare, so I decided to study abroad in London for a year through the Agency for Cultural Affairs’ Program of Overseas Study for Upcoming Artists, so I could also do something like that on my own. From there, I trained with the Royal Shakespeare Company and Théâtre de Complicité, created Machigai no Kyogen (The Kyogen of Errors), starred in Robert Lepage’s The Tempest and Jonathan Kent’s Hamlet, and I also directed performances of Hamlet and Macbeth myself. We just staged Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream in February 2025 as part of Mansai Creation Box Vol.3: Mansai’s Toy Box at the Ishikawa Ongakudo, where I have been serving as artistic creative director since 2024.

My father often says, “Kyogen must first and foremost be beautiful, then things like entertainment and humor will follow,” and I agree that the ultimate form of art is the pursuit of beauty. In other words, there’s a part of me that is resistant to just being a Kyogen performer. Of course that’s what I am, but if you pursue artistic expression, you are also an actor, singer, dancer, and key figure within the industry. We could say that my father’s generation thoroughly exemplified that potential, and I’ve continued to move things forward from there.

-

Machigai no Kyogen (The Kyogen of Errors, 2005) Photo: Shinji Masakawa

-

Horazamurai (The Braggart Samurai, 2021) Photo: Shinji Masakawa

-

Macbeth (2013), directed by and starring Mansai. Lady Macbeth: Natsuko Akiyama. Photo: Jun Ishikawa

- Can you tell us about the process of performing Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream?

- We added a narrative onto Mendelssohn’s composition and attempted to create a performance that wouldn’t just tell a story, but be about half music and half play. We likened the center stage orchestra to a forest and chose to develop various human dramas all around it, combining it with elements of Kyogen and Ryukyu dance. It was an opportunity for me to show how I could merge these different forms of Japan’s traditional performing arts, and I felt that they complement each other well in terms of having a balanced sense of both technique and potential for innovation. We also incorporated a bit of the theatrical elements that never came to fruition in the opening ceremony for the 2021 Tokyo Olympics.

For example, we took the idea of sansen somoku shikkai jobutsu, or “mountains, rivers, grasses, and trees can all attain Buddhahood,” based on Japanese polytheism, and although it’s not so straightforward when said out loud, we represented it with the hanagasa, or the Ryukyu flower hat. Since it’s an Okinawan play, I thought about incorporating the traditional Okinawan string instrument sanshin, but decided otherwise because Japanese and Western instruments have different sound-pressure levels. Although there’s a part of me that wonders if I made the right decision, I do think that, in the end, I was able to make sure the orchestra and play were in equal standing, instead of presenting a short play as part of a concert, or an orchestra pit on stage. I think I’m at a place where I’m really struggling with and also enjoying this new challenge of working with orchestras.

-

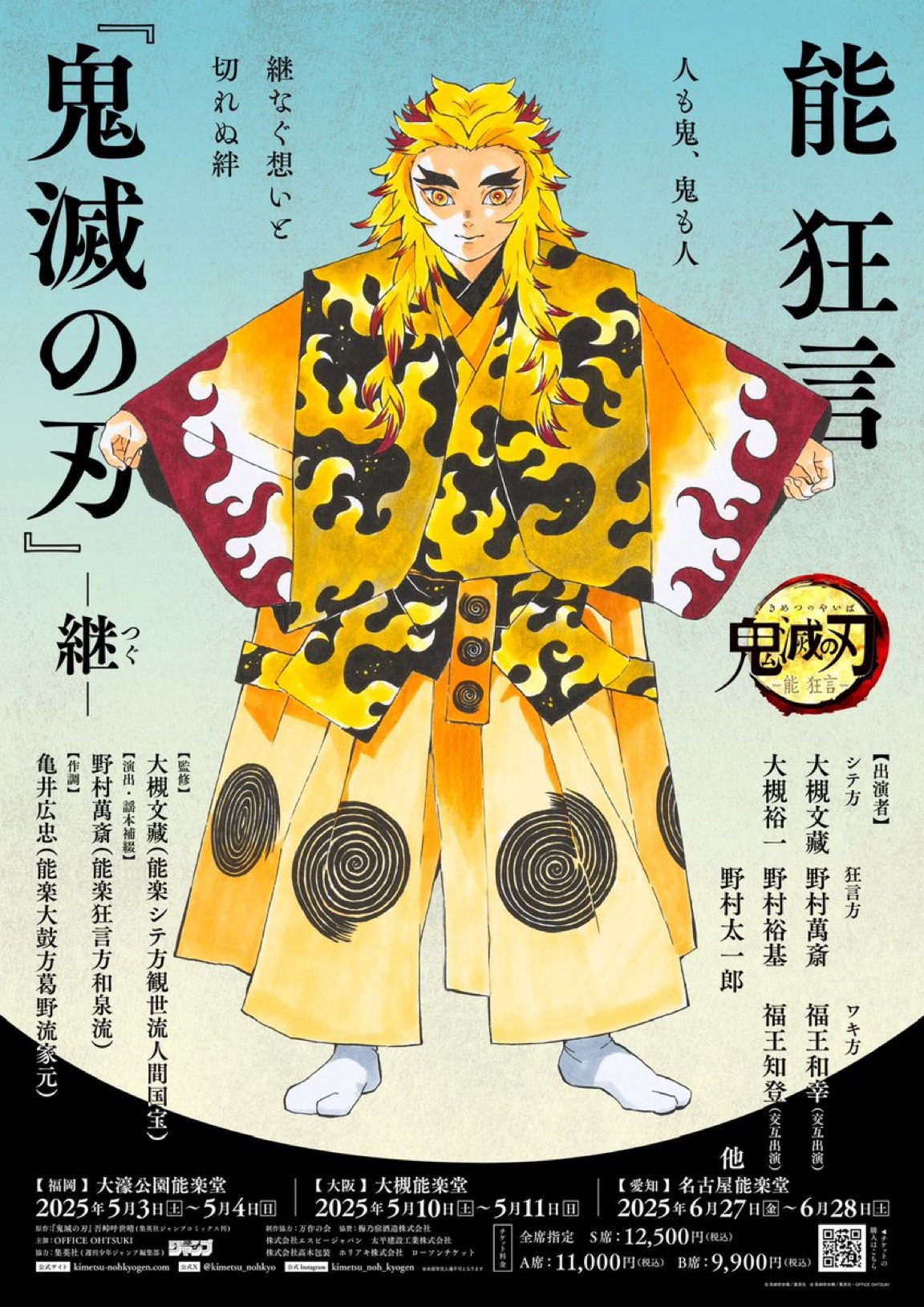

Noh and Kyogen: Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba -Tsugu (Continuation)-

June 27 – 28, 2025 at Nagoya Noh Theater

Original Work: Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba by Koyoharu Gotouge (published by SHUEISHA, Jump Comics)

Supervisor: Bunzo Ohtsuki / Director: Mansai Nomura / Music Arrangement: Hirotada Kamei

Cast: Bunzo Ohtsuki, Yuichi Ohtsuki, Mansai Nomura, Yuki Nomura, Taichiro Nomura, and others

Details: Official Website of Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba -Tsugu (Continuation)-

© Koyoharu Gotouge / SHUEISHA

© Koyoharu Gotouge / SHUEISHA, OFFICE OHTSUKI

- You’ve also been embarking on a new challenge of incorporating your learnings from Kyogen into manga and anime content. You directed, starred in, and adapted the utai libretto for Noh and Kyogen: Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba, based on the manga by Koyoharu Gotouge, which drew much attention and led to the performance of its sequel, Noh and Kyogen: Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba -Tsugu (Continuation)-.

- Adapting Demon Slayer9 into a Kyogen performance may have worked well because the story is set in the Taisho era (the first half of the 20th century). We tend to think of the Edo period (17th–19th century) as that of Kabuki, the common people’s performing art, but the abstraction in Kyogen, a samurai art born in the Middle Ages, can actually feel contemporary, and it goes well with the classical atmosphere of the Meiji (late 19th century) and Taisho eras.

“Tanjiro Kamado: Unwavering Resolve Arc” which we adapted in the first piece, depicts how demons are not simply monsters but tragic beings that used to have a human heart, and how Tanjiro empathizes with them. However, the “Mugen Train Arc” and the “Entertainment District Arc” that we feature in the second performance are much larger in scale, with demons haunting each train or taking over the entire entertainment district, so I feel like we partially pulled it off through sheer force. If we were to use an actual train, it would defeat the purpose of performing the piece in a Nohgakudo (Noh theater venue). Instead, we utilized the tsukurimono stage props of Noh, and lined up three of them at the hashigakari,10 and incorporated the shakuhachi flute to produce the sound of a whistle and taiko drums for the sound of the trains in motion. To top it off, we had carriages parked by each of the ichi-no-matsu (first pine), ni-no-matsu (second pine), and san-no-matsu (third pine) set pieces at the hashigakari. We even used LED lights for the battle scene between Akaza and Rengoku.

-

Noh and Kyogen: Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba -Tsugu (Continuation)-, “Mugen Train” Scene

© Koyoharu Gotouge / SHUEISHA

© Koyoharu Gotouge / SHUEISHA, OFFICE OHTSUKI -

Noh and Kyogen: Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba -Tsugu (Continuation)-, “Rengoku” Scene

© Koyoharu Gotouge / SHUEISHA

© Koyoharu Gotouge / SHUEISHA, OFFICE OHTSUKI

- Were you aware of the fact that these methods are often used in 2.5 dimensional musicals11?

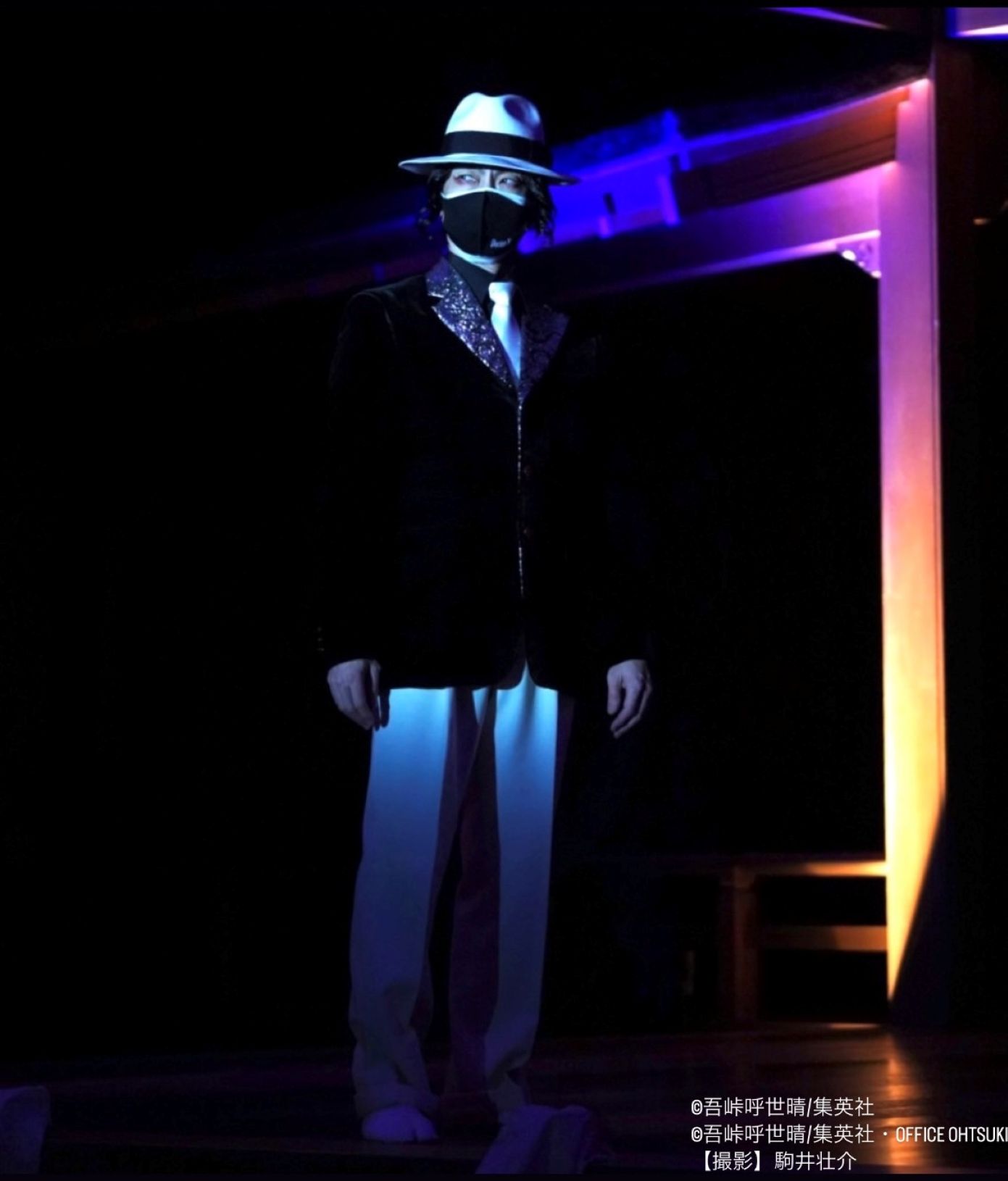

- It’s definitely a thin line to toe, since I didn’t want to simply mimic 2.5 dimensional musicals, but it’s also necessary to explain things that are difficult to follow.

For example, Muzan Kibutsuji generally wears Western clothes, but I didn’t want to suddenly present someone like that at the hashigakari, so I decided to have him jump on the Noh stage from the kensho (audience seats), as if he had been hiding among the audience. Tanjiro is also represented through a happi coat with black and green ichimatsu patterns and a chestnut-colored headband, instead of strictly following the original character’s look, and Zenitsu Agatsuma with a yellow happi and headband as well. I’m always thinking about how much to strip things down or to more directly reenact them.

It was rewarding to see how well the performances were received by Noh critics and researchers. After all, Noh was originally created and enjoyed by those who were interested in finding ways to reenact stories on the Noh stage that everyone had a base level of familiarity with. Reiko Yamanaka, who is a Nohgaku researcher and Demon Slayer fan, praised the performances, saying, “this is what Noh used to be like”.

-

Tanjiro Kamado (Yuichi Ohtsuki)

© Koyoharu Gotouge / SHUEISHA

© Koyoharu Gotouge / SHUEISHA, OFFICE OHTSUKI -

Zenitsu Agatsuma (Yuki Nomura)

© Koyoharu Gotouge / SHUEISHA

© Koyoharu Gotouge / SHUEISHA, OFFICE OHTSUKI

-

Muzan Kibutsuji (Mansai)

© Koyoharu Gotouge / SHUEISHA

© Koyoharu Gotouge / SHUEISHA, OFFICE OHTSUKI -

Rui (Bunzo Ohtsuki)

© Koyoharu Gotouge / SHUEISHA

© Koyoharu Gotouge / SHUEISHA, OFFICE OHTSUKI

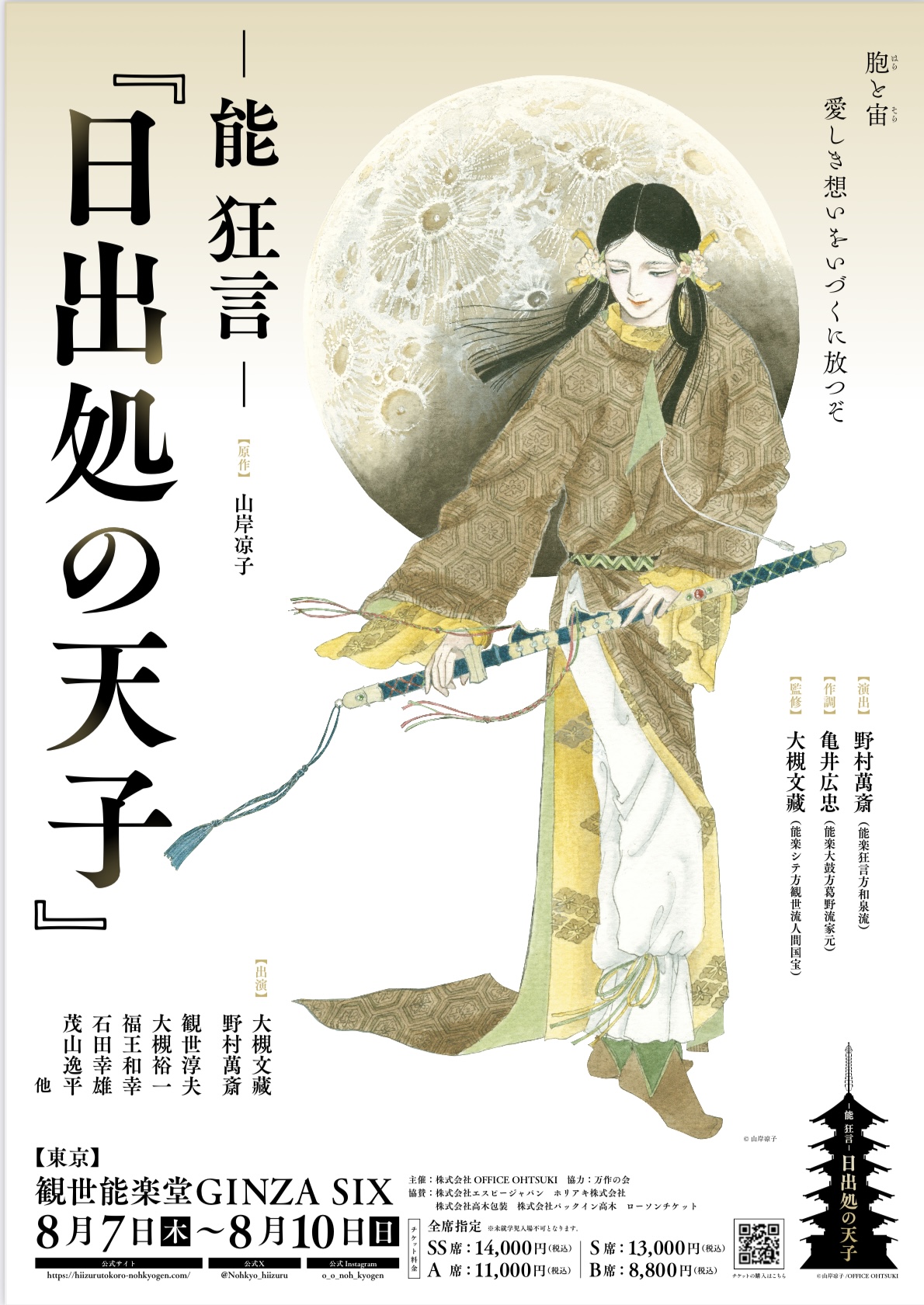

In the summer of 2025, you will be directing and starring in Noh and Kyogen: Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi, based on the original manga series Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi12 by Ryoko Yamagishi.- I recently had a conversation with Ryoko Yamagishi, and I think we will represent things differently compared to the action play depicting demons, given that it’s a very distinct historical drama; the work contains some occult elements, the characters are rulers of the Asuka period (6th–7th century), and the story also delves into the realm of homosexuality as well as the dichotomy between Buddhism and Shintoism. I received the first draft of the script the other day and talked about how I wanted to create the piece in a more Noh way, since we would have too many characters and things on stage if we were to strictly follow the original narrative.

- Does that mean focusing more on the philosophical realm, instead of sticking too much to the plot?

- Exactly. I feel that during that era, the presence of supernatural things that cannot be explained by science were much more prominent than they are today. An effective, nonverbal method to express that is to use the musicality of the hayashi (musical accompaniment) and the utai (Noh chants). Words are composed of both meaning and sound, and nowadays we mainly hear things that we understand, but—in a way—we also believe in the power of sounds that we can’t comprehend. Using that aspect of language, you can create the possibility for these big leaps, where the atmosphere becomes heightened without any logical explanation. I hope to emphasize that aspect in Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi.

-

Noh and Kyogen: Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi

August 7 – 10, 2025 at Kanze school Noh theater, GINZA SIX

Original Work: Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi by Ryoko Yamagishi

Supervisor: Bunzo Ohtsuki / Director: Mansai Nomura / Music Arrangement: Hirotada Kamei

Cast: Bunzo Ohtsuki, Mansai Nomura, Atsuo Kanze, Yuichi Ohtsuki, Kazuyuki Fukuo, Yukio Ishida,

Ippei Shigeyama, Hiroharu Fukata, Kazunori Takano, and others

Details: Official Website of Noh and Kyōgen: Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi

- With Japanese manga and anime having achieved a global level of popularity and recognition, I can imagine that the performance would garner attention from around the world.

- I would love to bring the performance overseas. Demon Slayer once did a takeover of the electronic billboards of Times Square in New York, so I think we could generate a big buzz too. I’m hoping we can create a quality project.

- You have been simultaneously working with these new endeavors as well as with the classics—what do you hope to achieve in the future?

- My hope is to not simply continue producing works, but to continue highlighting the potential of Kyogen as part of our identity, and by extension, highlighting the potential of Japan’s performing arts in general. In order to do so, I’ve operated under the belief that we sometimes need to go to the pitch on the other side and fight on their ground, rather than just sticking together on our own, and that’s how I’ve ended up where I am today [laughs]. I feel that I am standing as the successor to the generation of Hisao Kanze13 or my father, but I also feel like I don’t have the same kind of community that they did. Even so, in the course of performing not just Kyogen but also contemporary theater, as well as serving as artistic director of the Setagaya Public Theater, I’ve thought through many things and experienced a lot of trial-and-error working across various theaters. Although I’ve had to bite the dust at times, I’ve continued to gain new experiences without shying away from the unfamiliar. I’ve gone through my share of struggles and hardships, so I hope the next generation will also continue to work hard despite the challenges.

- It feels like you are passing down all of your treasured experiences to your son Yuki, not just with Kyogen, but with performances like Hamlet too.

- In this day and age, I think it’s essential for those inheriting traditions to understand these possibilities. However, Yuki and I are not the same person, and while in Kyogen you can bind yourself to the established forms to a certain extent, when you live in a world without these strict forms, you also have to figure out how to establish your own relationship to what’s around you. I’ve been fortunate to engage with many different people and gain rare experiences like working with Akira Kurosawa and Yukio Ninagawa, and some of these experiences have been beneficial for me, while others perhaps to my detriment. I also hope that Yuki will come to embody a different kind of potential than mine.

-

Sanbaso

In the Noh play Okina, the three performers are Okina, Senzai, and Sanbaso. First, Senzai dances using light steps, during which Okina dons a mask called Hakushiki Jo and then performs a more grave dance. Sanbaso follows, not wearing a mask during the first half of Momi-no-dan, then putting on the mask of Kokushiki Jo for the second half and dancing while ringing a bell. Okina is performed by a shite-kata Noh performer, while Senzai and Sanbaso are performed by kyogen-kata Kyogen performers, depending on the school of shite-kata.

-

Manzaburo Umewaka III

Manzaburo Umewaka III is a shite-kata Noh performer of the Kanze school who was born in 1941 as the eldest son of Manzaburo Umewaka II. He has led overseas performances for festivals including the Europalia ’89 Japan in Belgium, the Japan Festival 1991 in the UK, and the Noh performance in Berlin to celebrate the Japan Year in Germany in 1999. In 2001, he assumed the name of Manzaburo Umewaka III. He has been acclaimed not only for his artistry, but also for his work in breaking down and promoting the appeal of Noh.

-

Noto Peninsula Earthquake

The Noto Peninsula Earthquake occurred on January 1, 2024, and registered a maximum JMA seismic intensity of Shindo 7 in the Noto region of Ishikawa Prefecture. It caused widespread destruction of houses and led to tsunamis and landslides as well.

-

“Hiraki”

“Hiraki” is when one performs their first shite role for a major Noh piece in Nohgaku (Noh theater).

-

Onmyoji

“Onmyoji” was an official position in the early Middle Ages that used onmyodo (“The Way of Yin and Yang”) to perform divination and ward off evil spirits. Onmyoji (2001), directed by Yojiro Takita, is a film adaptation of Baku Yumemakura’s series of the same title, in which Mansai plays the lead role of onmyoji Abe no Seimei.

-

the Great East Japan Earthquake

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake and tsunami struck the eastern part of Japan, resulting in around 18,500 people dead or missing. The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident also occurred, leading to an unprecedented complex disaster.

-

Uzume’s dance

According to Japanese mythology, Amaterasu Omikami, the goddess of sun, became enraged by her brother Susanoo-no-Mikoto’s various misdeeds, and shut herself in a cave called Ama-no-Iwato. This caused the world to remain in a state of eclipse, and, at a loss as to what to do, the yaorozu no kami (eight million gods) decided to host a banquet in front of the cave, where Ame-no-Uzume-no-Mikoto performed a dance. Lured by the festive atmosphere, Amaterasu Omikami peeked outside, and Tajikarao-no-Mikoto opened the cave door to bring her out, which restored light to the world. Ame-no-Uzume-no-Mikoto’s dance is considered to be the origins of kagura, which is a form of ritual dance.

-

Mei-no-Kai

The group was formed in 1970 by Noh performers, shingeki actors, critics, playwrights, and directors, such as Hisao Kanze, Hideo Kanze, Shizuo Kanze, Mannojo Nomura (now Man Nomura), Mansaku Nomura, Kan Hosho, Hisano Yamaoka, Shuji Ishizawa, Masakazu Yamazaki, and Moriaki Watanabe. They performed a variety of works until 1976, including Greek tragedies and plays by Beckett, Atsushi Nakajima, and Kyoka Izumi. The group expanded the theatrical possibilities of Noh, highlighted its connections with contemporary theater, and played a pivotal role in collaborating with other genres.

-

Demon Slayer

Demon Slayer is a manga about Tanjiro Kamado, a young boy whose family was murdered by demons and who goes on a quest to become a demon slayer swordsman. Serialized in the manga magazine Weekly Shonen Jump from 2016–2020, the comic became a huge hit, selling over 150 million copies in total. The animated TV and film versions are also widely popular, viewed in more than 145 countries and regions around the world.

-

hashigakari

A hallway-like section that connects the age-maku, where the performers appear, and the main stage. Three pine trees are planted along its side, and starting with the nearest one to the main stage, they are each respectively called ichi-no-matsu, ni-no-matsu, and san-no-matsu.

-

2.5 dimensional musicals

Theater performances and musicals that faithfully reproduce the world of two-dimensional forms of media such as manga, anime, and video games on a three-dimensional stage.

-

Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi

A manga by Ryoko Yamagishi that was serialized in the shojo manga magazine LaLa from 1980 to 1984 and became a huge hit. Set against the backdrop of ancient Japanese history, the manga intricately depicts the complex relationships between Prince Shotoku, who popularized Buddhism in Japan with his supernatural abilities, and the people around him. The series has a devoted following to this day.

-

Hisao Kanze

Hisao Kanze is a shite-kata Noh performer of the Kanze school who was born in 1925 as the eldest son of Tetsunojo Kanze VII. Along with his younger brothers, Hideo Kanze and Shizuo Kanze (Tetsunojo Kanze VIII), he worked not only in the Nohgaku world but across an array of other theatrical forms, including his involvement in the aforementioned Mei-no-Kai and the performances of new Noh plays. In 1962, he studied abroad in France as the first student to be invited by the French government to participate in a Japan-France theater exchange program, where he studied under the French actor and director Jean-Louis Barrault. In 1974 and 1976, he formed the Zeami-za (Zeami Troupe), which toured internationally.

-

ⓒ Akihito Abe

Special thanks to Setagaya Public Theatre and OFFICE OHTSUKI