Ratri Anindyajati

The Landscape of Contemporary Dance in Indonesia’s Thriving Dance World: Tradition, Identity, and Collaborations across Asia in a Multiethnic Nation

Photo: Akihito Abe

Photo: Akihito Abe

Ratri Anindyajati

Born in Jakarta, Indonesia, Ratri Anindyajati is an independent producer. She is active in organizing within the performing arts, international arts festivals, and numerous nonprofit cultural organizations, and was appointed Director of the Indonesian Dance Festival (IDF) in 2022. Her work in promoting Indonesian performing arts to the globe spans a wide range of genres, extending beyond dance to include theater and fine arts. With a focus on international co-productions and cultural exchange at the national and regional level, Anindyajati fosters collaborations across various projects in arts and culture.

Indonesia, the largest archipelago in Southeast Asia, is home to over 17,000 islands and more than 1,331 ethnic groups (according to the 2010 census). The country has seen advancement in modern technology and culture, fostering a unique identity that is thriving alongside its rich ethnic diversity.

As Indonesia’s music scene continues to flourish remarkably, its dance culture has also experienced exceptional growth, with Indonesian dancers frequently performing at numerous international dance festivals. Indonesian dance is incredibly diverse, ranging from styles that demand an intense physicality to more stylized, intellectual works.

The Indonesian Dance Festival (IDF), established in 1992, stands as one of the earliest international dance festivals in Southeast Asia and the longest running. Despite facing significant hurdles—such as the Asian Financial Crisis and the fall of the dictatorship—the festival has kept the spirit of dance alive.

In 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic, Ratri Anindyajati was appointed director, bringing with her a wealth of experience from working domestically and abroad.

In this interview, she discusses her vision for the future, one rooted in decolonization and aimed at strengthening connections across Asian nations.

Interview/text: Takao Norikoshi

English Translation: Yume Morimoto, Monika Uchiyama (Art Translators Collective)

Background and Encounter with Dance

- Could you tell us about your background, your involvement in the Indonesian Dance Festival, the current state of dance in Indonesia, and your future international collaborations? To begin, can you share how you first encountered dance?

- My mother, Maria Darmaningsih, learned Javanese court dance, and later ventured into contemporary dance, so dance became a part of our entire family. When I was ten, my mother received a scholarship to study abroad for a Master’s degree in education, so she took the three of us children to the small university town of Lethbridge in Alberta, Canada. At the age of eleven, my younger sister and I performed the West-Javanese Peacock Dance at International Heritage day, an event celebrating diverse cultures. There was such an overwhelming response that we even appeared in the newspaper. That moment became a turning point for me, as it sparked my desire to share Indonesian culture with the world.

- Is it common for children in Indonesia to learn traditional dance?

- Indonesia has at least hundreds of ethnic groups, and dance is deeply ingrained in the culture. Jakarta, where I was born and raised, is unique because it is such a large city. My family is Javanese, so we practiced Javanese dance while my Balinese friends learned Balinese dance, and my Sundanese friends did Sundanese dance. In more rural regions it’s quite common for children to have some form of experience in traditional dance from an early age.

- How long were you in Canada?

- I was in Canada for four years. I took various dance classes, including ballet, hip hop, and I believed I would become a dancer. I returned to Indonesia in 2002 when my mother’s study abroad period ended.

- I understand that it was also a turbulent time due to the Asian Financial Crisis (1997) and the fall of Suharto’s dictatorship (1998).

- Yes. At one point, my mother even thought about having me stay in Canada until I graduated from university. In the end, we prioritized preserving our own cultural identity, so the whole family returned to Indonesia.

I attended the end of middle school and high school in Jakarta, and of course, I continued dancing. But when my parents got divorced, I saw my mother try to balance dance and raising children, so I felt then that pursuing a future as a dancer would be challenging.

Still, I wanted to be involved in the work of promoting culture, so I studied international relations and politics in Bandung with the hopes of becoming a diplomat. However, I felt that international politics was not for me, and I returned to Jakarta after graduating. It was there that I started going to Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM)1 and the Jakarta Institute of Arts, and I realized that this was the place where I was meant to be.

- From there, how did you become the Director of IDF?

- I had been involved with IDF since my university days, working as a liaison officer, interpreter, production coordinator, and international relations coordinator. Through these roles, I realized that there were very few arts managers in such areas within the dance industry. People were simply doing what they could to fill in the gaps.

I then started learning about arts management and worked freelance in Jakarta, but I soon found it difficult to make a living that way. That’s when I thought, “Why not pursue a scholarship and study arts management properly in Europe?” It was a rather colonial approach, but I ended up going to Los Angeles on a scholarship. There, I earned my MFA in Creative Producing and Management while continuing to help with IDF remotely.

Gradually, I established myself in arts management in Los Angeles, and in 2019, IDF was hiring a program manager for the 2020 edition. I applied for the role despite my hesitations, and soon after, the COVID-19 pandemic began. IDF took place amid the pandemic without a director, and I served as program manager. In 2022, I was offered the role of Director. I will elaborate on this later, but IDF is an organization that my mother was also very much involved in. I was unsure of whether to accept the offer back then—but now, here I am as Director.

About IDF

- Could you tell us about how IDF was established? When it was launched in 1992, was the contemporary dance scene already thriving?

- Prior to IDF, in the late 1970s, there was the Festival for Young Dance Arrangers, which was founded by Jakarta Arts Council. At that time, Sal Murgiyanto was a member of the Dance Committee of Jakarta Arts Council. It was a festival for young dance arrangers (the term “choreographer” was not widely used at that time). At that time, my mother was a traditional Javanese dancer from Yogyakarta, and Nungki was a young dancer active in her hometown of Jakarta.

Although this festival was quite successful, it ended in the 1980s when Sal moved to Taiwan to work at an art university. After that, there was no longer a place for young choreographers to showcase their work and connect with each other. Nungki and my mother started teaching at the Jakarta Institute of Arts, but whenever Sal returned to Jakarta, they would talk about the necessity of a new platform. Eventually, the three of them and another co-founder, Melina Surya Dewi, took the initiative to establish IDF in 1992 with support from other professors at Jakarta Institute of Arts.2

-

From the 1st IDF in 1992 ⓒIDF

- In the beginning, was IDF more of a platform for emerging Indonesian artists, rather than an international festival?

- From its inception, IDF was intended to be an international festival, although the first edition featured only Indonesian choreographers. By 1993, the festival began to include works from neighboring countries like Singapore and Malaysia, though it remained relatively small in scale, with the festival period only lasting about three days. Later, the festival began collaborating with the World Dance Alliance,3 which helped it quickly grow on an international scale, starting with Southeast Asia.

- As mentioned earlier, five years after IDF was established, there was a period of upheaval with the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 and the fall of the dictatorship in 1998. Did this have any impact on the festival?

- Yes, it did. The currency crisis prompted IDF to adopt a biennial format, and while the festival did not take place in 1999, it managed to continue without much impact even after the political reformation. This was largely because it was privately managed without public funding.

- Could you elaborate on “private management”?

- In the early days, IDF was funded through donations from supporters of the founders—Sal Murgiyanto, my mother Maria, Nungki Kusumastuti, and Melina Surya Dewi. The Jakarta Institute of Arts supported them by providing the venue, but I don’t think they contributed financially. Over time, we began reaching out to companies for sponsorships, allowing the festival to be held in 1998, 2000, 2002, and biannually since then.

-

From left: IDF founder Maria Darmaningsih, Melina Surya Dewi, Nungki Kusumastuti ⓒIDF

-

Taman Ismail Marzuki(TIM)

Taman Ismail Marzuki is a cultural complex in central Jakarta that includes four theaters, a museum, planetarium, and movie theater on its premises.

-

other professors at Jakarta Institute of Arts

These professors included Tom Ibnur, Deddy Luthfan, Farida Oetoyo, Julianti Parani, and Sardono W. Kusumo.

-

World Dance Alliance

The World Dance Alliance (WDA) is an international nonprofit organization that promotes the exchange and recognition of dance in all its forms. It provides a platform that connects people working in the dance scene, including dancers, choreographers, educators, researchers, and managers.

It was officially founded in 1990 as the Asian Pacific Dance Alliance at the Hong Kong International Dance Conference, later expanding to WDA America (1993), WDA Europe (1997). The organization is currently expanding its activities into Africa.

Contemporary Dance in Indonesia

- When did contemporary dance make its way into Indonesia, and through what channels?

- We believe that contemporary dance doesn’t only come to us from the external world. Rather, we also have to see the dynamics and histories of our local contexts. We cannot measure what is modern and what is contemporary through only a linear Western lens because our experiences as a nation are very complex and diverse. Indonesia also has such a profound post-colonial experience. In the context of Jakarta, several dance practitioners and scholars saw the emergence of contemporary dance as marked by the founding of Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM) in 1968, which facilitated the growth of the artistic community with a space and environment where freedom of exploration could take place. This became the platform for the birth of new dance works that shift from tradition and the contemporary, for both artists who live in Jakarta and those who come from outside of the capital. Of course, the dynamics in other cities are different and require in-depth reading to understand.

- Have any foreign artists had a notable impact on Indonesian contemporary dance?

- Yes, foreign artists have played roles in the development of Indonesian contemporary dance, as a result of their artistic curiosity as well as larger geopolitical, economic, and cultural currents. However, the impact of foreign artists has never been one-sided. Indonesian artists and institutions actively shape cross-cultural exchange and the influence is reciprocal. In early post-independence Indonesia, the Stichting voor Culturele Samenwerking (STICUSA), established in the Netherlands in 1948, actively promoted cultural cooperation between the Netherlands and its former colonies, influencing cultural practices to this day. In the 1950s, under president Soekarno, many cultural diplomacy policies were implemented by presenting Indonesian performing arts abroad. In return, Indonesia received many visits from foreign artists, organized on the government level and privately managed. In 1955, the Martha Graham Dance Company toured Indonesia and Asia, which was a visit organized by the US government. Following that, American institutions invited several Indonesian artists to study in the US, including Bagong Kussudiardja, Seti-Arti Kailola, and Wienoe Wardhana. These cross-cultural engagements left a lasting imprint on their artistic paths and on the shifting landscape of Indonesian dance.

How IDF is Currently Operated

- What is the scope of IDF’s current budget and where does the funding come from?

- In the beginning, the organization was volunteer-run with no one receiving salaries, and even in the early 2000s, directors were lucky if they were reimbursed for transportation. As of 2024, our budget is approximately 4,900,000,000 IDR. While this provides the minimum budget needed for our festival team to work for a year and a half to prepare, it still doesn’t allow us to pay artists what they should be.

In 2018, the then president launched the Law on Advancement of Culture, which created various grant opportunities. We were recognized as one of Indonesia’s oldest private arts organizations, and in 2022, we received three years of funding from the Ministry of Culture. However, the government’s intention was for us to develop an infrastructure to create our own funding by the end of the three year period, which is very unrealistic—but we are still actively working toward it. 2024 is our final year of funding, but it is based on fiscal years so we are able to use the money until June of 2025. The funding is partially put toward the festival, and the remainder is used to sustain the organization.

In 2019, the three co-founders that I mentioned earlier started a foundation that functions as our umbrella organization, restructuring the festival’s operational framework. They currently serve as our board members.

- How many staff members are there?

- There are six of us for daily operations. With the substantial grant we received from the ministry, the administrative workload required for creating reports is heavy, so four of our team members are dedicated to that task. We are currently preparing a festival report to submit to both the Ministry of Culture and Ministry of Finance.

- Besides the six paid staff, are the rest volunteers?

- Yes. We gradually build our team as the festival nears, but the six main staff work throughout the year on both the foundation and the festival. In addition to the secretary and accountant, there is also an in-house curator who programs the festival with me, and a festival manager. We also have part-time staff that handle marketing and visual design. We’re quite busy year-round organizing public programming like mini festivals and online classes.

- Are you based at a specific theater or dance venue?

- We don’t have a dedicated theater, so instead we rent and collaborate with venues. Our main venue is TIM, but with some of the theaters owned partially by the Jakarta City Government, and partially by private entities, the management is a bit messy. In the past we were subsidized, but now we pay to rent the theaters. But we have a collaborative relationship with Komunitas Salihara Arts Center who continue to subsidize our programs.

-

Main venue of IDF: Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM) ⓒ IDF

- Can you tell us about the dates, number of performances, participating countries, and the selection process for the 2024 IDF program?

- I worked with four curators on the program: Linda Mayasari, Nia Agustina, River Lin from Taiwan, and Arco Renz who is based in France and is engaged in various projects in Asia. Linda was previously director of the Cemeti Institute for Art and Society, and Nia is an independent curator and founder of the Paradance Platform. People from the international scene have always been involved because we haven’t had the budget or infrastructure to allow us to see works abroad.

Although the festival was held across seven days in 2022, the festival was shortened to five days in 2024 due to our funding from the city of Jakarta being reduced to half. There were five evening performances, six Kampana performances by young choreographers (which will be discussed later), one site-specific work, and participants from six or seven countries.

The selection process is democratic, where we each propose works to the group and discuss them together. We also receive submissions from artists, but we prioritize suggestions from the curatorial team.

When we invite international artists, we receive governmental or institutional support from their countries (such as the Japan Foundation, Göethe Institut, British Council, among others). In those instances, we may be recommended an artist that the country wants to promote, but personally, I would prefer (especially recently) to make selections based on the IDF curatorial team.

-

IDF curators. From second left: Arco Renz, River Lin, Linda Mayasari, Nia Agustina ⓒIDF

- What kind of works are selected for IDF?

- We want to focus on works that critically reflect our times, because dance can communicate topics that are difficult to discuss openly in our society. Although dance is our main focus, we’ve included visual artists and theater actors who approach dance through a critical lens since before I joined the organization.

- Are there restrictions on political, religious, or homosexuality-related themes, or performances involving nudity? In the past you’ve invited Boris Charmatz who is known for his nude performances.

- We still deal with censorship. Although the times and society are shifting, we still have to be cautious because we receive funding from the federal government and the city of Jakarta. We’ve never presented full nudity, but in such situations we would find a way, such as holding invitation-based closed performances. I personally feel moved by politically charged and challenging works.

The 2024 edition of IDF had many works that engaged with queer and nonbinary identities. There was a work by a Taiwanese artist featuring a gender nonconforming dancer, and there were concerns that Indonesian audiences would interpret the performance as “a pole dance by a man dressed as a woman.” The only thing that ended up happening was that we received a phone call from the Jakarta City Government, who we receive funding from, urging us to make sure that press or media do not attend the event.

- Outside of performances, what other kinds of programs are part of IDF?

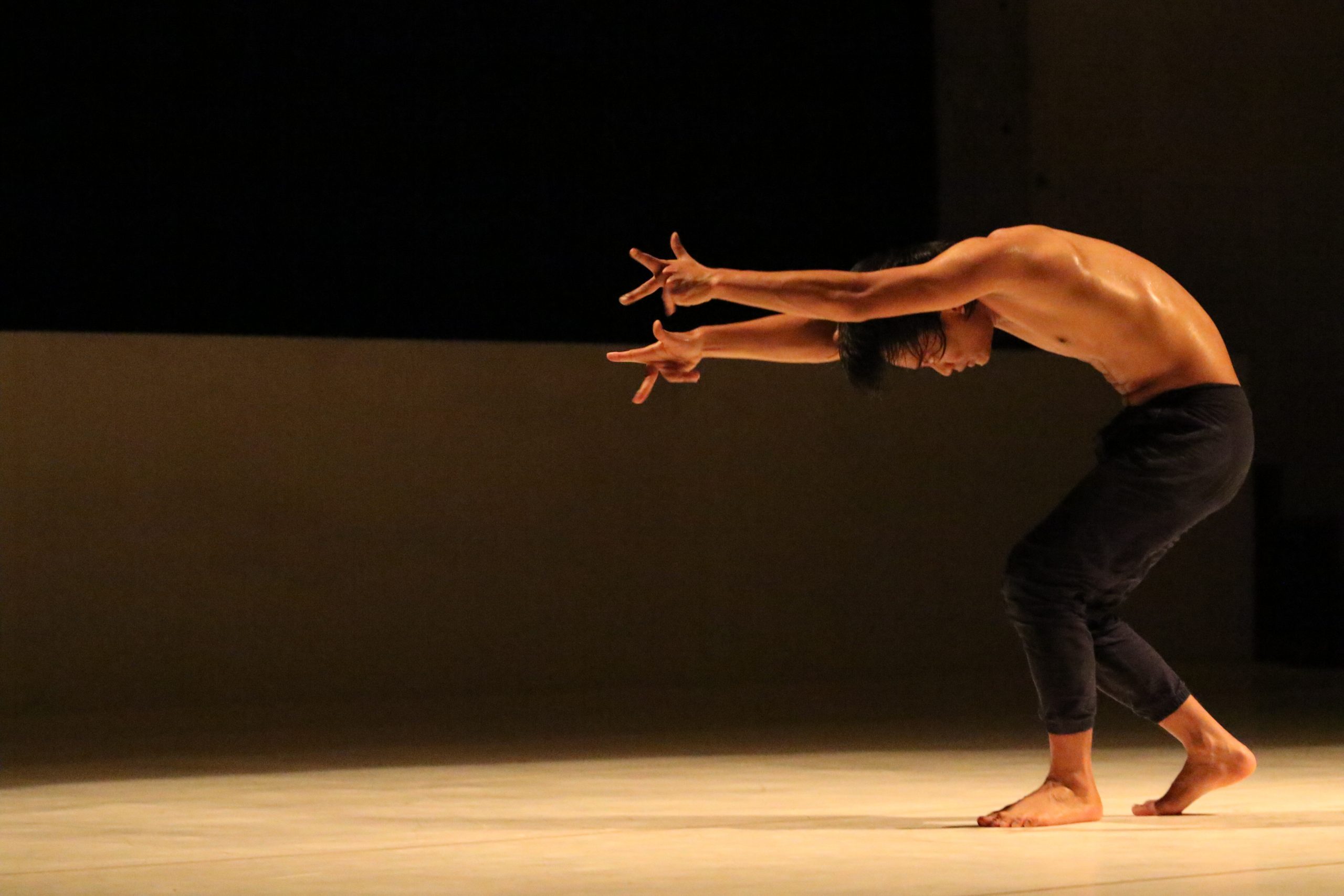

- We have workshops, masterclasses, and public discussions, so education is an important core of the festival. The evening performances are works by mid-career and established artists. There is also the Kampana program for emerging young choreographers. In this incubator program, which began as a showcase in the 1990s, the artists attend three workshops where mentors (Nia Agustina, Arco Renz, and Linda Mayasari) provide feedback. We facilitate the development of their ideas for one year, culminating in the presentation of their work in progress at IDF. Although the program was originally limited to young Indonesian choreographers, we have extended it to include Southeast Asian choreographers. Our 2024 edition featured six participants (two choreographers and four Southeast Asian artists).

-

From IDF 2024 ⓒ IDF

- Are networks within Southeast Asia important to IDF?

- IDF has a thirty year history, and is the longest standing dance festival in Southeast Asia. It has operated as a window to the diverse culture of Indonesia and Southeast Asia. While carrying the festival’s legacy forward, I also want to think about what we can do for the younger generation. Sustainability of the festival is our biggest concern, and I think it is important for the various platforms in the region to contribute what they can to support one another.

- Are you considering collaborations with Japanese artists?

- Of course. I participated in KYOTO EXPERIMENT this year and learned about experimental and contemporary performing arts within the Japanese context. There are many experimental programs coming out of festivals across Asia under new leadership, and I hope that we can collaborate by sharing resources and programs. I’m especially excited for artistic exchange and for works to travel between Asian countries.

- How would you describe the young generation of Indonesian dancers, and how do they relate to traditional dance?

- Indonesia is made up of 17,000 islands and diverse ethnic groups, so it is difficult to generalize. Until recently, many dancers were educated at arts universities, and I used to confidently say that most contemporary dance is rooted in tradition, but it has become more diverse in recent times. There are many contemporary dancers without formal education who have backgrounds in street dance, hip-hop, ballet, or even non-dancing backgrounds. This was a noticeable trend in the past two editions of Kampana.

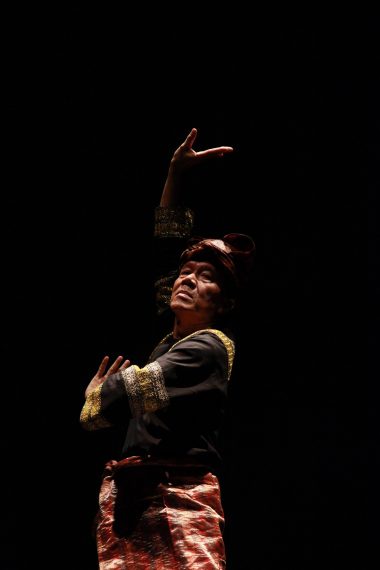

- Who are some important Indonesian dancers?

- Huriah Adam from Sumatra, and Gusmiati Suid, who founded Gumarang Sakti, one of our first contemporary dance companies. Defying patriarchal society, Gusmiati moved from Padang to Jakarta, and as a single mother who smoked cigarettes, she was a symbol of resistance (smoking is considered a male activity in some regions).

Dancers and choreographers who are already internationally recognized like Eko Supriyanto, Jecko Siompo, Boy G. Sakti are also wonderful. But Boy has since quit dancing after becoming an ardent muslim, saying that “artmaking is considered a sin.” Boy’s ex-wife, Hartati, is still active as a choreographer. These three are in their 50s.

Also notable are Julianti Parani and Farida Feisol, who have backgrounds in ballet, as well as the Japan-based dancer Rianto, Martinus Miroto from Yogyakarta (who passed away in 2021), and among those in their 40s, Fitri Setyaningsih.

-

Huriah Adam ⓒIDF

-

Gusmiati Suid, “Seruan” (2010) ⓒ IDF

-

Eko Supriyanto ⓒ IDF

-

Rianto, based in Tokyo ⓒ IDF

- I recently saw Puri Senja perform at a festival in Singapore. Moh Hariyanto (also known as Hari Ghulur), who has collaborated with Reisa Shimojima, is also a dancer with a powerful physicality.

- Puri is part of a dance company founded by Hari Ghulur from Surabaya, and also participated in the Kampana program with her own work in 2020. It’s not that other promising young dancers do not exist, but it is a challenge for dance artists to sustain their practice, and they need support.

- The group photograph of the IDF team features mostly women. Is the gender balance of the staff intentional?

- The current composition of the team happened organically. It’s partially in the DNA of the festival as a platform that nurtures the younger generation. On the other hand, arts management is still not a popular profession, particularly for men. I notice that there are more female producers and arts managers around us, and men tend to not choose the profession of arts management. Although our staff’s pay is low, and we cannot provide health insurance or retirement plans, I try to maintain our workplace as a safe space that is open to people in vulnerable conditions.

- What are your goals for IDF in the future?

- When we collaborate within Asia, I think it’s important that we do so while considering decolonization. We must discover our own contemporaneity without referring to the West. I went to the US to study, and I learned there that their system isn’t perfect either. In order to find our own ways of doing things, I hope that we can share our social capital, cultural capital, and ancestral knowledge. And I also hope to create an environment where the West can learn from us (the East), and for more equity to be distributed between the Global North and South.

-

Photo: Akihito Abe

Interpretation: Tomoko Momiyama

Related Tags