Kie Yamamoto

A New Generation of Masterful Designers – The Unique Life and Stage Philosophy of Kie Yamamoto

Photo: Akihito Abe

Photo: Akihito Abe

Kie Yamamoto

A set and costume designer, she graduated from the Department of Integrated Psychological Sciences, School of Humanities at Kwansei Gakuin University, and subsequently completed the Theatre Design program at Arts University Bournemouth and a postgraduate degree in Theatre Design at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, both at the top of her class. Her notable works include set and costume design for Dodo’s Free Fall (written and directed by Takuya Kato), Breaking the Code (directed by Kae Inaba), Heartland (written and directed by Ryo Ikeda), and Robot (directed by Seiji Nozoe), as well as set design for Watako Wa Motsureru, Itsuzoyawa (both written and directed by Takuya Kato), and Wild Grey (directed by Shuko Nemoto). She was awarded the 31st (2024) Yomiuri Theater Award for Outstanding Staff for her set designs in Heartland and Watako Wa Motsureru, and the 32nd (2025) Yomiuri Theater Award for Outstanding Staff for both set and costume design in Robot.(Updated April 2025)

With a minimalist yet bold and intellectually refined aesthetic, Kie Yamamoto brings sculptural beauty to the stage, sparking the audience’s imagination even before the performance begins. Since making her debut in Japan with Nam-Ham-Da-Ham in 2017, she has collaborated with a series of rising playwrights and directors, injecting fresh energy into the Japanese theater scene.

Her journey into scenography and costume design began with an early passion for fashion, which led her to pursue rigorous professional training in the UK. Upon returning to Japan, however, she found herself without mentors or connections in the industry and momentarily abandoned her dream of working in theater. Then, in a twist of fate, she received an unexpected offer from Mirai Moriyama, a renowned actor and dancer—someone she had only briefly spoken to years prior. This serendipitous opportunity opened the door to her career as a professional scenographer and costume designer.

Defying the entrenched apprenticeship system with sheer talent, Yamamoto represents a new wave of creators reshaping the landscape of Japanese theater. Here, she shares the story of her unconventional journey and her philosophy with regard to scenography.

Interview/text: Aki Ichikawa

“I Got My Start in Fashion”

- You studied psychology at a Japanese university before graduating top of your class from both Arts University Bournemouth in England and a postgraduate program at Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama. When did you first become interested in set and costume design?

- Originally, I was deeply involved in music. I began learning violin at age three, and later picked up piano, trumpet, and even played in a band during my student years. I also loved fashion and secretly dreamed of pursuing a career in that field, though I never had the courage to tell my parents. Since I was also an avid reader and fascinated by criminal psychology, I decided to study psychology in university. However, when it came time to think about a career, my passion for fashion reignited. Because my father, a researcher, often took me to academic conferences abroad, I was familiar with traveling overseas, which made the idea of studying fashion abroad feel natural. To prepare, I spent a year at the Japan College of Foreign Languages in a department specializing in overseas arts studies.

Yet, once I began studying fashion in earnest, I realized I wasn’t drawn to the commercial aspects of the industry—the focus on “what sells” didn’t resonate with me. I loved movies as well, so I thought that maybe costume design would be a better fit. Although one of my preparatory school teachers recommended I consider architecture, I ultimately chose costume design and applied to Bournemouth. Since the entrance exams there emphasize creative processes like sketchbooks, my preparatory school gave me a wide range of assignments, from the basics of costume and textiles to abstract topics like “what is identity?” I was completely immersed in my studies.

- So you originally went abroad intending to study costume design, not set design?

- That’s right. When I entered Bournemouth, out of 70 students, only 10 were international, and I was the only Asian student who wasn’t a native English speaker. In the UK, it’s common for designers to handle both set and costume design, and at Bournemouth, the curriculum was changed to cover both from the year I entered. So I was rigorously trained in the fundamentals of both set and costume design over three years. Until the year before I graduated, international graduates were allowed to stay in the UK for two more years without conditions. Unfortunately, that policy was abolished just as I graduated. Since I had no theater experience in Japan, I felt I couldn’t yet return home, so I decided to pursue a master’s degree.

I was accepted to a postgraduate program at Royal Welsh College that is very small and selective—and extremely tough. It was a year of rebuilding everything I had learned at Bournemouth. In fact, almost all my foundational skills, like making stage models, I acquired at Royal Welsh College. Building models is considered very important in the UK—some people even make a living just by building them. That’s when I realized that I’m actually really good at making models! [laughs]. I attended every single class over four years, never late and missing a day. It was hard, but I loved it and fully realized that this is what I want to do.

-

Graduation ceremony of the Theatre Design program at Arts University Bournemouth, UK (2012).

-

With the cast and crew of The Lower Depths, performed while enrolled in the Postgraduate Theatre Design program at the Royal Welsh College of Music & Drama, UK (2013).

- You mentioned that at preparatory school, you were once advised to pursue architecture. When you started studying set design again, what aspects made you feel that this field suits you?

- Set design shares a lot with architecture in terms of structural thinking, and it also overlaps with fine art and interior design. But unlike fashion, you don’t have to think about “selling” or “customer needs.” I’ve always loved art, installations, and fashion, so I guess I’ve always been drawn to three-dimensional objects. In that sense, set design naturally suits my personality. Many of my classmates in grad school came from art, literature, or architecture backgrounds, which made me appreciate how theater draws influence from everywhere. I think it’s fortunate that I have a wide range of interests. Both set and costume design begin with reading the script, and my lifelong love of books really helps. Looking back, I realize that this career beautifully integrates all the things I’ve loved since I was a child.

- What was your first encounter with theater?

- I think the first stage production I saw was a musical for children that my parents took me to when I was in elementary school. But I was a rather cheeky child and remember thinking it was lame [laughs]. Later, when I was a middle schooler, my father took me to New York on a conference trip, and we saw Cats. That was thrilling. After that, because one of my mother’s acquaintances was working as a sewing assistant for Lily Komine, who designed costumes for Yukio Ninagawa’s productions as well as for Gekidan☆Shinkansen, I had the opportunity to watch the dress rehearsal. I was especially blown away by Mirai Moriyama’s performance in Goemon Rock (2008). I had already been watching his films, but from then on, I actively sought out all his stage work.

A Winding Path to Becoming a Set Designer

- After graduating from Bournemouth and Royal Welsh College, how did you begin working professionally as a set designer?

- To be honest, I faced a significant setback right after finishing my postgraduate studies. When I returned to Japan, I had no connections in the theater world. Through an introduction by the only set designer I knew, Kazue Hatano, I visited set designers in Munich and Berlin to explore possible opportunities, but nothing materialized. Later, I was offered a chance to work at a scenography school in the Netherlands and applied for the Overseas Study Program for Emerging Artists offered by Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs, but unfortunately, I wasn’t selected. At that point, I gave up on pursuing work abroad and returned to Japan, where I took a full-time job at an interior display company.

It was during that time, quite unexpectedly, that Mirai Moriyama—whom I had briefly spoken to at a film screening in London—reached out to me. After that screening, we had only exchanged a few polite messages on social media. So it was a real surprise when he suddenly sent me the project proposal for Nam-Ham-Da-Ham (2017) 1 and asked me if would like to work on this with him. That’s how I met playwright and director Hideto Iwai. I realized that if I didn’t take this chance, I might never get another. So I made the bold decision to quit my job, and while working part-time at the study-abroad college I used to attend, I also began taking on stage design and costume design projects.

Honestly, I owe so much to Moriyama—so much that I feel like I should enshrine him on a home altar [laughs]. I never apprenticed under a specific set or costume designer, and since I had returned to Japan with zero theater experience there, I can only say that an incredible stroke of luck brought me to where I am now.

-

Nam-Ham-Da-Ham (2017) Photo: Nobuhiko Hikiji Courtesy of Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre

- Stage design plays a crucial role in bringing a director’s vision to life, making it essential to build a shared understanding and strong relationship of trust with the director. You’ve continued to collaborate with Iwai, including on Wareware No Moromoro (nos histoires…) at T2G Théâtre de Gennevilliers, France (2018). In 2019, you began working with emerging and highly creative directors such as Yuri Yamada, Ryo Ikeda, Shuko Nemoto, and starting in 2021, Takuya Kato—all of whom you seem to maintain ongoing collaborations with.

- Yes, I’ve known Ryo Ikeda since he was the assistant director on Nam-Ham-Da-Ham. He feels like a younger cousin or the kid next door to me [laughs]. The first time he asked me to handle set design for him was for the production Sugata created by his company, Yumei. At that time, the script was delayed, and since I got tired of waiting, I took the liberty of creating the set on my own. Ryo ran around the rehearsal space like a kid with a new toy and said, beaming, “I didn’t realize how much easier it would be when someone else does the set!” Up until then, he had designed his own sets, so I imagine it felt liberating for him. Nowadays, I feel a bit like a proud relative watching the kid I cheered on grow up.

-

Sugata (Premiere, 2019) Photo: Keita Sasaki Courtesy of Yumei

- Do you often take the initiative to propose your own design ideas?

- Yes, I usually make the first move. When working with a director for the first time, I might ask them for key concepts, but ideally, I like to receive the script as early as possible.

For example, since Poni (2021) by Takuya Kato’s Takumi theatre company, I’ve worked with him on about eight productions, including revivals. One thing about Kato is that he finishes his scripts incredibly fast—sometimes he just sends it suddenly out of nowhere, way ahead of schedule. After reading it, I might casually tell him what I’m thinking and share my design ideas, and he makes decisions quickly, too. He loves art, and I feel like we share a similar sensibility when it comes to things we dislike or find uncool.

On the other hand, Ikeda is slower with scripts, but we have a relationship where I can say, “Just send me half for now.” For Heartland (2023), the script was really late, so I created the set almost entirely on my own. But he sometimes uses the space in ways that exceed my imagination. Because he used to do sculpture, his sense of spatial awareness is unlike any other director I know. He and I share similar tastes as well.

Now that I think about it, maybe directors who didn’t come into theater straightaway are more interested in working with me. Kato, Ikeda, Yamada, and Nemoto all have broad interests and chose theater as their medium—I think that openness is something we share.

Kae Inaba, whom I worked with for the first time on Equal (2022, written by Kenichi Suemitsu), originally comes from the world of film. In particular, Breaking the Code (2023)2 was a landmark production for me. I’d always wanted to do a play that involved historical research, but because many contemporary plays in Japan are newly created, I hadn’t had the chance to work on a period piece. I loved being able to lease vintage suits from specialty shops and create realistic costumes. I also think we succeeded in evoking the atmosphere of 1940s and 1950s Britain, a style I adore.

What Inaba and I have in common is that neither of us is interested in staging a classical play exactly as written—even for something like Shakespeare. We share a commitment to reinterpreting and reconstructing classics to speak to contemporary audiences. That’s what makes our collaboration so exciting. She’s also an art lover and pays close attention to costume details, down to the choice of earrings. Both Nemoto and Yamada also love fashion, and I find that working with female directors often means a rewarding attention to detail when it comes to costumes.

-

Poni (2021) Photo: Hanayuki Higashi Courtesy of Wawon Kikaku

-

Heartland (2023) Photo: Keita Sasaki Courtesy of Yumei

-

Nam-Ham-Da-Ham

A theatrical work born out of Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre’s children’s workshop series “Kodomo Hassha Project,” which transformed children’s ideas into stage performances. Created, directed, and performed by Hideto Iwai, Mirai Moriyama, and Kenta Maeno, the work later inspired the NHK Edulcational TV show Odomo TV, specifically the segment “Odomonogatari.”

-

Breaking the Code

Written by Hugh Whitemore, premiered in London in 1986. The play follows the life of real-life British mathematician Alan Turing, focusing on his complex and tragic journey in the 1940s and 1950s.

-

Breaking the Code (2023) Photo: Shinsuke Sugino Courtesy of Gorch Brothers

Costumes as Character Design

- In Japan, there are still relatively few designers who handle both set and costume design as you do. What do you find fascinating about costume design?

- For me, costume design is essentially character design. Whenever I draw a costume sketch, I always include the character’s face and think about their pose. I enjoy imagining the personality, background, and psychology of each character. Looking back, I think my love of reading since childhood, as well as my studies in psychology at university, have shaped how I approach costume design. Although my career path has been full of twists and turns, I believe that without a certain amount of life experience, it’s difficult to imagine a character in depth.

Costumes shouldn’t merely move on stage, nor should they draw too much attention to the actor themselves. The real joy of costume design lies in making the actor become the character through what they wear. That’s why I need the script before I can even begin thinking about costumes. Whether it be the set or costume, I feel uneasy unless I have the scale model and the costume designs ready by the first day of rehearsal.

- Designing both set and costume creates a unified world on stage. Do you prefer to work on both when possible?

- Definitely. Many directors I work with request that I handle both set and costume, and I’m grateful for that. But I would also like producers to recognize the value of having one designer oversee both.

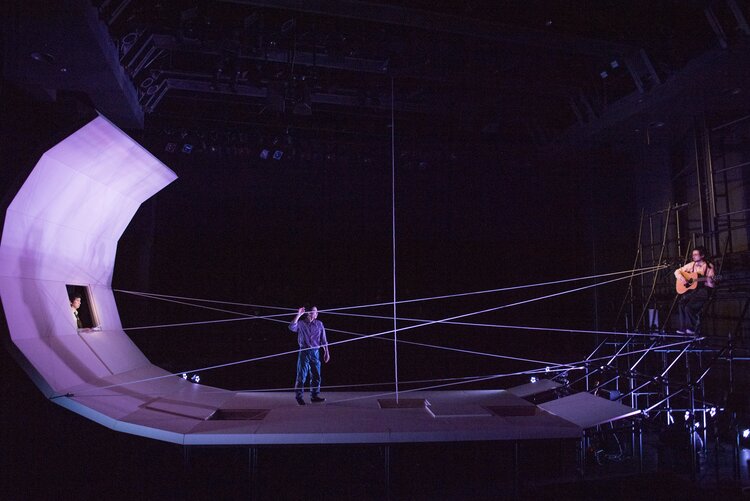

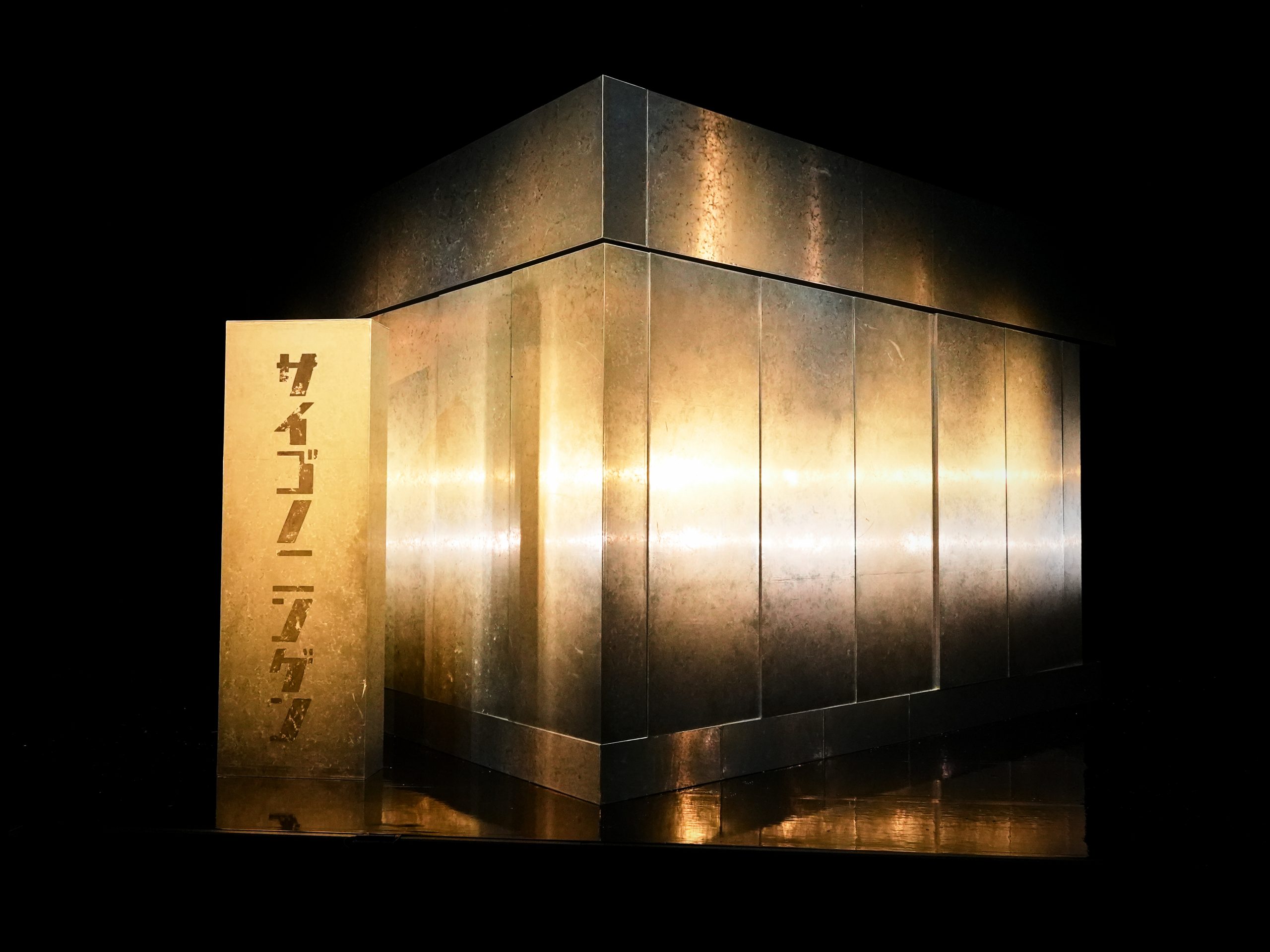

For instance, Robot (2024, by Karel Čapek) was a production where I was asked—by a producer I had never met before—to take charge of both set and costume. It was also my first collaboration with director Seiji Nozoe. In fact, on the first day of rehearsal, something unprecedented happened: a major change to the set design. After presenting the model to the entire team, I received an apologetic email from Nozoe saying, “I’m sorry, but after hearing the script reading, I feel I need to change the set.”

We had been refining that design through five months of meetings, but Nozoe is such a kind person that I suspect he found it difficult to raise the issue earlier [laughs]. Although we had many discussions afterward, in the end, he thankfully made effective use of the set. Painting the set silver was especially challenging because metallic paint doesn’t easily achieve the desired sheen. The entire set-building crew at Haiyuza Theatre worked together to repaint it. It truly felt like a collective creation. For that production, I was honored to receive the Yomiuri Theater Awards Outstanding Staff Award for both set and costume design. But I see it as an award that belongs to everyone who worked so hard on that show.

- Set and costume design are both deeply connected to lighting.

- Absolutely. One of my greatest concerns on any production is who will be designing the lighting. I have deep trust in Yukiko Yoshimoto, a lighting designer known for creating stunning designs with minimal equipment. Since I also favor a minimalist approach, we share a strong creative affinity. Fortunately, Nozoe also likes Yoshimoto’s work, so I had the fortune of collaborating with her on Robot.

-

Robot (2024) Photo: Shinji Hosono Courtesy of Setagaya Public Theatre

-

Robot (2024) Photo: Shinji Hosono

- Your set designs are often simple yet bold, full of inventive metaphors and variety. What is your creative process like?

- I always start from an abstract concept. From there, I gather images of artworks and installations, and then have conversations with the director. When working on classic translations, I read every relevant academic paper I can find, and I always research the author. I also write out my design plans in full sentences first. I transcribe notable quotes from research papers and repeatedly read the script to extract keywords. My first reading is usually casual, but then I read it aloud, analyzing it scene by scene: who appears, what happens, and so on.

That’s why I never use a tablet—I always dedicate one sketchbook to each production. Writing by hand helps me organize my thoughts. This is why having the script early is crucial for me. Kato’s scripts in particular are very easy to read. If I wanted, I could breeze through them quickly, but since he often embeds deeper meaning in his works, I read them over and over, carefully reflecting on their layers.

-

A handwritten sketchbook created for each production. Photo: Akihito Abe

- The recent revival of Kato’s Dodo’s Free Fall had significant changes in both script and design compared to the premiere.

- Yes, it felt like working on an entirely different piece, as though I were watching a version from a parallel world. In the re-staging, Kato sent me photos of a long sofa along with keywords like “corners” and “waiting room.” Since I knew he wanted to focus on the protagonist’s perspective, I proposed a set with climbable elements. It was wonderful to see how effectively he used the set in the end.

On the Future of Japanese Theater: Education and Systemic Reform

- Having studied abroad, what do you see as the challenges facing Japan’s theater industry?

- The biggest issue is compensation, especially when I’m asked to do both set and costume. In the UK, there’s always a costume supervisor responsible for sourcing costumes. Although I appreciate being entrusted with both roles, without at least one assistant, I’ll get burned out. I really wish people would provide personnel budgets that reflect the workload.

As I myself experienced when I returned to Japan and struggled to find work, the same group of set and costume designers tends to dominate the scene, and I hope to see this situation change. In the UK, if you have ability, age doesn’t matter—you can be hired right away. Their educational system ensures that by the time you graduate, you’re ready to work professionally as a designer. Even assistants get properly paid. I think the biggest problem in Japan is that young designers cannot make a living in this field. Without connections, it’s extremely difficult to break into the industry, because many opportunities rely on mentor-student relationships. Frankly, I’ve been lucky to get to where I am, but many of those who came before me who studied costume design in the UK gave up after returning to Japan because they had no way in.

For example, at the National Theatre in London, they hire two assistant designers each year from specialized schools. These assistants work with various external designers, allowing them to build a network, and by the end of the year, they are given the opportunity to design one full production on their own. I really wish public theaters in Japan would adopt a similar system. If we do not reform both education and the system itself so that young artists can afford to pursue these careers, they will give up on doing so. Graduates should be given opportunities based on talent. Whether this will happen in my lifetime, I don’t know, but I do hope to rise to a position where I can help create a system that provides opportunities to young talent.

-

【Related Information】

KAAT Atrium Project Late April – Mid-June 2025 at KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theater | Details

Stage Play Rinse, Repeat April 17 – May 6, 2025 at Kinokuniya Southern Theatre TAKASHIMAYA | Details

Gekidan Futsu’s Himitsu (Secret) May 30 – June 8, 2025 at Mitaka City Arts Center, Hoshi no Hall | Details

Related Tags