Hiroko Murata

Setting out to create new performances in London—Umegei’s method of expanding worldwide and nurturing creators for the future

Hiroko Murata

Born in Nara Prefecture, Hiroko Murata is the Director of Umeda Arts Theatre UK Limited. As a theater producer, she has successfully led numerous projects and performances since the 1990s. Highlights include Yashagaike (Demon Pond, 2005), a collaboration with a film director; Bring Me My Chariot of Fire (2012, 2013), a Japanese-Korean co-production staged in both countries; and the world premiere of the Broadway musical Prince of Broadway (2015). In addition to inviting international productions to Japan, in recent years, she has provided opportunities for Japanese theatermakers to gain hands-on experiences in the British industry, leading to the production of Violet (2019), One Small Step (2024), and Tattooer (2024), which were all collaborations between artists from both countries. Currently based in both Japan and London, her innovative productions have been breaking new ground within the Japanese theater world. (Updated in March 2025).

As a child, Hiroko Murata became mesmerized by the artistry of Torvill & Dean, a legendary ice dance duo. Now based in the United Kingdom, the home country of the skaters she idolized, she leads Umeda Arts Theater’s International Department and develops various new productions to further the theater’s global presence.

She has presented a series of bold works that have taken the Japanese performing arts community by surprise: in 2019, she produced Violet, a musical directed by Shuntaro Fujita that was performed in London and Tokyo; then, in the fall of 2024, she produced premiering works by emerging Japanese playwrights at the Charing Cross Theatre, a historic Off West End venue, with bilingual actors who performed in English.

Seeing the potential of the performing arts as an “industry,” she has explored ways to build non-hierarchical collaborative relationships, learning from the successes of Broadway and Off West End. At the same time, she provides young Japanese creators with hands-on opportunities to work abroad and nurture their talent, and sends off new performances to the international stage. In this interview, we delve into her background and philosophy as a theater producer who is currently breaking new ground with her innovative business model.

Interview/text: Nobuko Tanaka

English Translation: Hibiki Mizuno, Ben Cagan (Art Translators Collective)

- Tell us how you decided to pursue a career as a theater producer.

- I studied art management as an economics major in college, and entered the job market in the early 1990s. At the time, commercial firms and banks were doing well, and various companies were investing in theater, music performances, and art exhibitions as mécénat (corporate arts funding) initiatives, and theater was still underdeveloped as an industry. I found this situation curious since the art form was firmly established as a business abroad. For example, while young directors in the UK were making their West End debuts in their twenties, things were slower in Japan, where aspiring directors would still be assistants in their thirties and finally premiering their shows in their forties. Given the long-held custom of apprenticeships, the career pace for producers was even slower—you would finally be an independent producer in your fifties. I strongly felt that there was something off about this slow pace.

I already knew in my twenties that I wanted to work as a theater producer, so I looked for companies where I could achieve that goal during my job search. Instead of applying to theater companies in Tokyo that already had a solid track record, I set my eye on Theater Drama City, which felt like a blank slate in that it hadn’t put out many in-house productions despite owning a venue in Osaka, and I landed a position at Hankyu Corporation, its parent company. Seeing that this industry, which wasn’t growing at the time, had the potential to really flourish, I decided to work in entertainment. In that way, my entry into the theater world was not because I had a passion for the art itself, but due to its business prospects. I saw the industry’s potential and how it wasn’t turning profit when it could definitely be lucrative, and this situation actually piqued my interest.

- What brought your attention to the international scene at a certain point?

- In 2005, Umeda Koma Theater and Theater Drama City merged into Umeda Arts Theater (Umegei),1 and we staged Yashagaike (Demon Pond)2 under the direction of Takashi Miike as a project to create theater with a film director. Since this was a rare idea at the time, the collaborative performance and adaptation between different fields in art was highly acclaimed. When I was thinking about what to do next, Tomotsugu Ogawa (now Chairman of Umeda Arts Theater and Takarazuka Live Next), who was my boss at the time, asked whether I wanted to develop the theater’s presence in Tokyo or go to New York City.

Since I hadn’t accomplished anything yet in Tokyo, I decided to transfer there in 2008, but in the previous year, Umeda Arts Theater commissioned the Viennese version of the musical Elisabeth, which was probably the largest commission at the time. Although the performance only took place in Osaka, given that the Tokyo edition was a concert, I felt like this was an incredible achievement, that the global stage was maybe not as far as I had imagined. It was also a commercial success and the first time that I saw how a production this large in scale could still turn a profit with a domestic venue in Osaka, without touring to Tokyo. I also learned that we could make it work in the entertainment industry even with international casts instead of popular Japanese actors, which motivated me to venture abroad.

So then I worked on Bring Me My Chariot of Fire, a co-production with the National Theater of Korea, which was written and directed by Wishing Chong (performed in Tokyo and Osaka in 2012; Seoul in 2013). We received a great response for this sold-out show, so this led to our next challenge to work towards Broadway.

-

Elisabeth, a Viennese musical (2007) Photo: Umeda Arts Theater

- So you started to fully venture abroad with this move into Broadway. What was the reaction like there?

- I realized that our connections with people could lead to creating things together, just as Wishing Chong had led us to working with the National Theater in Korea. From there, I first produced a concert called 4Stars in 2013, which featured three world-class musical stars (Lea Salonga, Ramin Karimloo, and Sierra Boggess) and Yu Shirota. I didn’t have any personal connections to the three international stars, so I simply approached their agents. We also established an office in New York in 2014, since at the time Broadway seemed to be more influential than the West End.

After 4Stars, I produced Prince of Broadway in Japan, with an outstanding team of all-Tony winners: Harold Prince (director),3 Susan Stroman (co-director, choreographer), Jason Robert Brown (musical director, arranger), and William Ivey Long (costume designer). It all started because Prince sent me a letter asking if Umegei would produce his show, since Broadway producers weren’t interested.

Jason Robert Brown was the musical director and Daniel Kutner was the director for 4Stars, and they both studied under Prince, so I think they told him that Umegei had been putting on some bold productions. Since the cast we invited for 4Stars were top Broadway stars, maybe Prince thought we were theater producers capable of paying a reasonable fee. We successfully produced this show, which premiered in Tokyo, and I learned firsthand that commercial success trumps everything on Broadway. Harold Prince stands unparalleled in his contribution to Broadway, as well as in training and nurturing talent, so I was very shocked that he was struggling to find a producer there who was willing to invest in his final musical about his personal journey.

This experience led me to take a step back from the Broadway money game and look for a place where we could take our time to create performances. We closed our New York branch and switched gears to think about how to create something unprecedented on a world scale at the West End.

-

The world premiere of Prince of Broadway in Japan(2015) Photo: Umeda Arts Theater

- Could you expand on your relationship with Thom Southerland,4 theater director and former artistic director of Charing Cross Theatre, and his key role in Umegei’s venture into the UK?

- I started working with Thom Southerland, who was in his early thirties at the time, around 2014. We felt the importance of investing in young talent like him, so together with Thom, we produced a work from scratch called The Illusionist, in an aim to create something with young theatermakers, whether they be directors or fine artists. It was scheduled to premiere in the UK, and we had already secured the performance rights there, but due to the coronavirus pandemic, the production unfortunately fell through. We managed to present a concert version in Tokyo in 2021, and we will finally premiere the long-awaited full show in March 2025.

At Umegei, we also decided to produce works with Japanese creators that could resonate with an international audience, in addition to inviting foreign directors to Japan. In terms of The Illusionist, rather than having the entire team made up of British staff, we brought in the set designer Rumi Matsui and costume designer Ayako Maeda to the British production team to explore an international approach to creating the show.

As a separate topic, I also consulted Thom about the lack of creators when putting together productions in Japan. The conclusion we ended up with was that education and nurturing talent was the only way forward. So I asked Thom to help provide opportunities that are simply unavailable in Japan for young creators to pursue their training.

At the time, he was the artistic director of Charing Cross Theatre, so he offered us a slot in the theater’s schedule. Our first aim was to nurture a director who could create musicals, so I approached Shuntaro Fujita.

Aside from adaptations of globally renowned manga and anime, original Japanese musicals face a huge hurdle in getting staged abroad, which is further complicated by performance rights issues. Fujita and I looked for a piece that would be able to clear these obstacles, and found the Broadway musical Violet.

When I was staying in London with Fujita in 2019, we did some research together. Although there were Japanese musicals that had participated in stage readings or festivals with a brief run, there was no precedent for what we did with Violet, running a show for two and a half months. There was no room for Japanese directors to wiggle their way into the London market. Fujita was able to direct a performance there because Thom and the owner of Charing Cross Theatre took a leap of faith. My hope was for Fujita to channel this really tough experience into his shows in Japan, and given his subsequent outstanding work, I’m really glad we went through with it.

By starting with Violet, we were able to get an understanding of the hurdles we’d have to overcome going forward in ushering Japanese artists to the global stage. It was crucial to bring uniquely Japanese productions. I was made painfully aware of the fact that we couldn’t rely on adaptations of foreign works.

So, in 2020, as our second initiative, we planned to do a stage adaptation of an original work by the film director Makoto Nagahisa, and I went to London with him to do some preliminary research. Since I was totally captivated by one of the film scripts that Nagahisa wrote, I wanted to bring it to life on stage. But it sadly fell through due to the pandemic.

Given our experience with these two projects, I suggested reviewing Umegei’s strategy to our team, which led to producing two performances back-to-back at Charing Cross Theatre, both directed by young Japanese theatermakers.

-

The London edition of Violet (2019), directed by Shuntaro Fujita. After its premiere in London, the musical had a limited three-day run during the pandemic, followed by a rerun in Tokyo and Osaka in 2024. Photo: Scott Rylander

- Although I still vividly recall the performances of One Small Step, written and directed by Takuya Kato, and Tattooer, written by Takuya Kaneshima and directed by Hogara Kawai, I was surprised by your decision to present new works by such young artists. How do you go about discovering young and promising artists?

- Before the pandemic, I would go see quite a few performances on my own, so I think that gave me plenty of opportunities to encounter talented young artists. Since the pandemic, I have staff members who can read plays and are skilled at discovering interesting emerging artists, and I have them thoroughly searching for me. There’s only so much ground you can cover on your own, so we split into teams to find promising talent. I have our staff select cutting-edge works from all kinds of sources, like books, films, and poems.

We weren’t able to present an original play when we worked with Fujita, and I still wanted to take on that challenge on the international stage, so I chose playwrights who I felt would contribute significantly to the Japanese theater scene in the future. Another criterion I had in mind was that they possessed a distinct style of theater. I wanted to see how Kato’s play, written in contemporary Japanese, would be received abroad. With Kaneshima, I wanted to draw out his more junbungaku (“pure literature”) background, so we asked him to create a play based on The Tattooer by Junichiro Tanizaki, one of Japan’s literary giants. Kawai caught my eye because of his ability to express his beliefs and distinct style when directing, no matter the time or location, even outdoors or in a small theater. I also offered him the role because I knew he had enough of a thick skin to withstand the psychological pressure of working abroad. In this way, our company went back to the drawing board and reaffirmed our commitment to provide opportunities to young Japanese artists. In doing so, we decided to take on the financial risks; our intention was to select creators of a generation for whom this experience could function as a backbone 20 to 30 years down the line.

Although these shows didn’t do so well from a business standpoint [laughs], I hope they can boost the morale of theatermakers in Japan, even just a bit.

We received mixed reviews from critics, but I think it’s significant that Kato, Kaneshima, and Kawai gave their all to make these works, and we earnestly accepted the results, myself included. I’m confident that these artists will make use of their experiences in future works.

I do believe that these plays have the potential to reach a global audience, if they are further refined and offered reruns. Whether our company has the capacity to go that far will be something that needs to be discussed internally.

Along with our focus on creating and refining original works, I also hope we can focus on developing Japanese commercial entertainment in London. Nurturing talent and profitability are tightly related; I believe that focusing solely on profitability gradually depletes the entire theater industry, so I want to develop both aspects.

-

The London premiere of One Small Step, written and directed by Takuya Kato. Photo: Mark Senior

-

Tattooer, written by Takuya Kaneshima and directed by Hogara Kawai, premiered in Japan and toured to London. Photo: Mark Senior

- Going back to square one, why do you think it’s important to expand overseas right now?

- Since Japan has a declining population, the number of theatergoers isn’t going to get any bigger. In the UK, children are taken to theaters starting from kindergarten, so there’s a habit of attending theaters as part of daily life. So then, it’s either that Japan aims to create that kind of culture, or steps up its strategies around international promotion, like Korea, to increase the number of international audiences that see Japanese theater. I think we first have to grow the market and the number of theatergoers in order to improve the quality of the performances. Venturing overseas is important in terms of increasing the number of people who see the work. For example, in order to have audiences abroad to see Kato’s plays, in addition to people in Japan, we have to show them in London.

As long as humans don’t lose their ability to think as humans, I believe that theater still has the potential to be financially viable. However, if we no longer think for ourselves in the future, we may find ourselves at a crossroads.

The theater crisis isn’t just a Japanese phenomenon, it’s talked about here in London as well. In addition to increasing ticket fees, there are more performances with limited-edition castings of celebrities, similar to Japan, and fewer works that pursue “art for art’s sake.” In this way, London is also facing a critical situation.

The other day, I went to see a pantomime (a comedic play packed with songs, dances, and slapstick jokes for children), a Christmas staple, but most of the audience members were older people, and surprisingly few were children. When I talked to several of the audience members, they shared how it has become an annual tradition for them because they grew up with it. In other words, their current consumption of theater is tied to their childhood experiences. In the same vein, if mothers today don’t take their kids to pantomime shows, they will lose that custom, which will in turn decrease its audience numbers. When I thought of that, I felt the impending risk of a cultural crisis in theater’s future.

- Going forward, what kind of international productions does Umegei hope to undertake?

- We want to become a part of London’s theater industry. Just as Umeda Arts Theater, which started with the business model of purchasing full productions, has now grown to consistently produce its own works in Tokyo, we hope to present works in the same way in London as well. Of course, some productions will lose money, while some will become huge hits. Going through those successes and failures, we hope to firmly ground Umegei’s works within the London scene. From Osaka to Tokyo to London to the world––all of us stand together in our commitment to build a globally beloved Umegei brand and continue our journey to develop as an international entertainment company.

Our current aspirations abroad⁵ are still in their early stages; we’ve just found the starting line. Having produced these few performances by young directors, I firmly believe that the only way forward is to always remember and believe in our original aim to nurture Japanese talent and not shy away from the necessary risks.

-

In 2005, Umeda Koma Theater and Theater Drama City merged into Umeda Arts Theater (Umegei)

Umeda Koma Theater, a predecessor of Umeda Arts Theater, was opened on November 16, 1956 by Umeda KOMA STADIUM CO., LTD. Degradation of the building caused the theater’s later closure, on September 28, 1992. On November 2, 1992, it reopened as “Theater HITEN” at the current location of Umeda Arts Theater, but it was changed back to “Umeda Koma Theater” in April 2000. On April 1, 2005, Hankyu Corporation reopened the theater alongside Theater Drama City, renaming it “Umeda Arts Theater” (commonly known as Umegei) , and it continues to operate under that name to this day.

-

Yashagaike (Demon Pond)

Yashagaike (Demon Pond) is a fantasy play by Kyoka Izumi (1873-1939) based on the “Ryujin” (dragon god) legend. In 2004, Umeda Arts Theater produced and staged an adaptation by Keishi Nagatsuka under the direction of filmmaker Takashi Miike, based on Masahiro Shinoda’s 1979 film version.

-

Harold Prince

Harold Prince is an American director and producer known for legendary hit musicals such as West Side Story, The Phantom of the Opera, Cabaret, Fiddler On The Roof, Evita, and Follies. He holds the record for the most Tony Awards won by an individual, having received 21 awards.

Prince directed long runs of The Phantom of the Opera at both the West End and Broadway. -

Thom Southerland

Thom Southerland is a British theater director, and the current artistic director of Mayflower Theatre in Southampton, England. His productions of Parade, Titanic, Grand Hotel, and Mack and Mabel at the Southwark Playhouse, a small-scale theater in London, were all met with critical acclaim, garnering significant attention. In particular, the 2013 revival of Maury Yeston’s Broadway musical Titanic won numerous national and international awards. Rising quickly in the musical theater world, he was appointed Artistic Director of the Off-West End Charing Cross Theatre in 2016. In Japan, he has directed Umeda Arts Theater’s productions of the musicals Titanic (2015, 2018), Grand Hotel (2016), and The Pajama Game (2017), all of which received critical acclaim. His involvement in these Japanese productions led to his significant contributions to Umeda Arts Theatre’s efforts to expand into the UK. He invited emerging Japanese theater artists to Charing Cross Theatre, where he had previously served as Artistic Director, staging co-productions between Japan and the UK.

-

Our current aspirations abroad

With the aim of expanding its international presence, Umeda Arts Theater has established a new subsidiary company in London called Umeda Arts Theatre UK Limited in February 2025, which will serve as one of the co-producers for The Hunger Games: On Stage, an upcoming show in the UK. The performance is based on the international bestselling novel The Hunger Games, which also inspired the global blockbuster film series. This first-ever stage adaptation will premiere at the new state-of-art venue Troubadour Canary Wharf Theatre in October 2025.

-

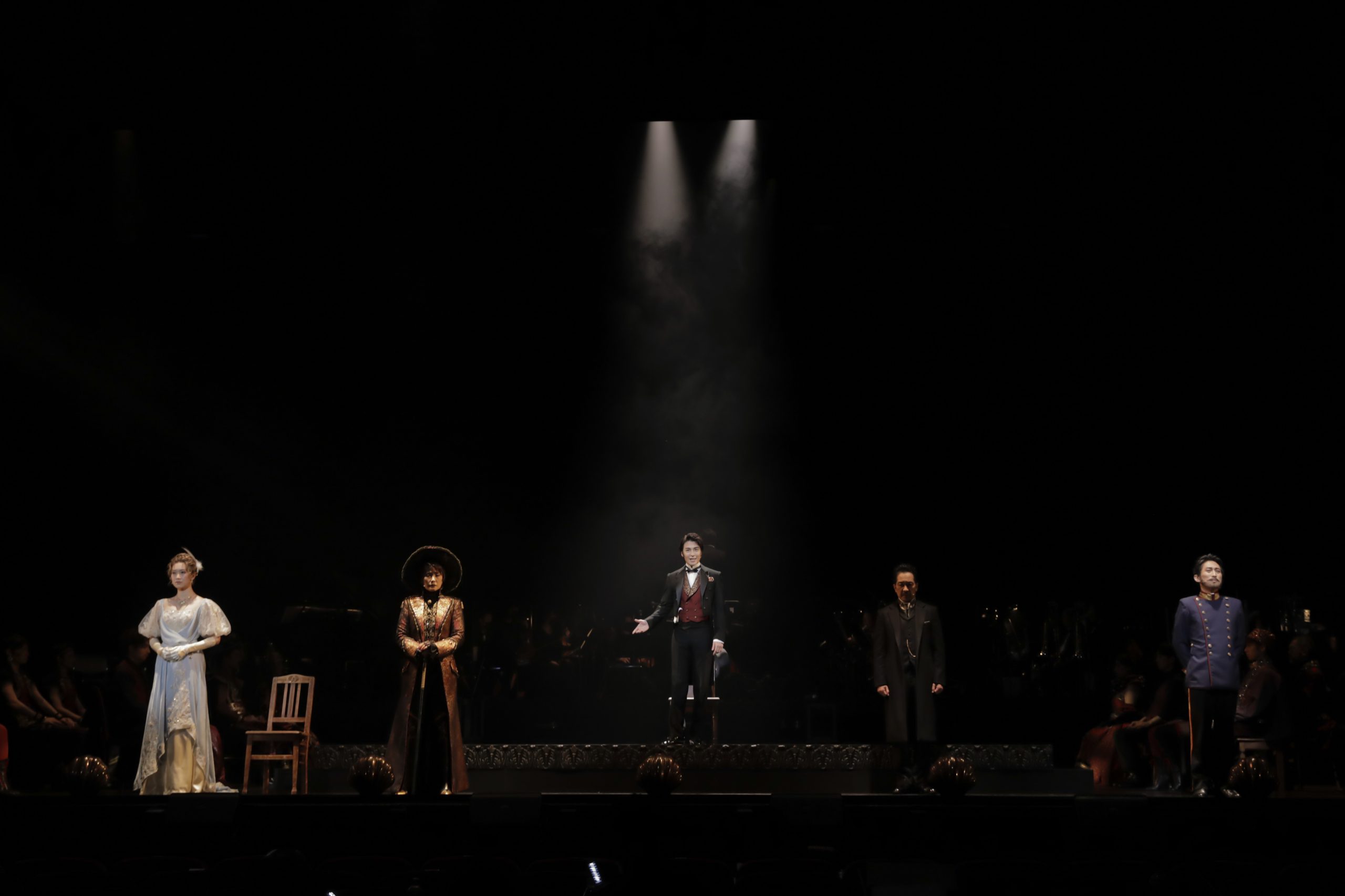

A concert version of The Illusionist (2021) was presented during the pandemic. The full musical premieres in 2025. Photo: Chisato Oka

Director: Thom Southerland

Featuring: Naoto Kaiho, Songha, Reika Manaki, Hideo Kurihara, Megumi Hamada

Tokyo: March 11–29, 2025 at Nissay Theatre

Osaka: April 8–20, 2025 at Umeda Arts Theater – Main Hall –

The Illusionist website

-

Special thanks to Umeda Arts Theater Photo: Shinobu Ikazaki

Related Tags