Choi Seok Kyu (Kyu Choi)

Building a Network to Face the World from an Asian Perspective: Choi Seok Kyu

Photo: Leo Yamamoto

Photo: Leo Yamamoto

Choi Seok Kyu (Kyu Choi)

Festival director, producer, and researcher Choi Seok Kyu is artistic director of Seoul Performing Arts Festival (2022-26) and creative director of Performing Arts Market in Seoul (2020-22). Choi focuses on important themes in contemporary art, conceiving and holding creative research residencies, labs, workshops, and many other projects. He has acted as festival or creative director of many events, including the UK/Korea Season Festival 2017-18, the Chuncheon International Mime Festival, and the Ansan Street Arts Festival. In 2005, he established AsiaNow Productions, helping greatly to internationalize Korea’s theater world. In 2013, Choi organized the Asian Producers’ Platform, a collaborative network of producers in the Asian region with the aim of planning and promoting projects, and building solidarity between performing arts professionals in Asia.

Name in Korean: 최석규(Updated September 2024)

His goals? To escape the Eurocentric values that remain deeply rooted even in Asia, engage with works from the personal perspectives of those residing in Asia, and provide an opportunity for near-yet-distant neighbors to get to know one another better. Seoul Performing Arts Festival (SPAF) Artistic Director (2022-26) Choi Seok Kyu has been a key player for many years in his work to build an Asian performing arts network. His unique project with Asian peers, the Asian Producers’ Platform (APP) Camp, invites performing arts professionals from the Asia-Pacific to gather in an individual capacity and spend a week together building deeper relationships. A former participant, Yoshiji Yokoyama (Literary Section, Shizuoka Performing Arts Center), spoke to Choi Seok Kyu about Asian artistic solidarity.

Interview: Yoshiji Yokoyama

English translation: Claire Tanaka

- Thanks to the APP you organized, I made several dozen friends across Asia and now no matter where I go there’s somebody I can go to for advice. To start us off, I’d like to ask about your motivation for creating APP. Before that, Asian producers often encountered one another on Western platforms, did they not?

- We had our first meeting in 2013 in Seoul and began holding the APP Camp in 2014. It started with a desire to rethink producers’ creativity and build up solidarity among Asian independent producers. Also, our identities as Asians and our ideas of what it means to be contemporary are changing daily and I wanted to revisit how artists look at Asia, search for a direction together between artists and producers, and find a way forward through collaboration. Finally, while the situation might be a little different in Japan, politics tends to steer the arts in many Asian countries, and the position of the arts can be unstable as it is affected by how the government happens to be leaning. We wanted to think about how to create a horizontally oriented platform for independent Asian producers.

- Why did you want to focus on Asia? After all, especially when it comes to contemporary performing arts, it tends to be more difficult to showcase Asian works than Western ones.

- I studied in the UK and in the early phase of my career I was mainly engaged with Europe. In the early 2000s, I became aware of an attitude shift within myself from the European view of Asian contemporary art to asking what sort of perspective Asian people themselves should have of their own contemporary arts. In 2005, I decided to create a new production company with my colleague Park Jisun called AsiaNow Productions, led by creative producers working. We based our activities on three pillars: Touring Now, Developing Now, and Generating Now. With Touring Now, we did international tours with Korean theater works. Developing Now was about making international collaborations between Europe and Asia, or countries within Asia. Generating Now was a laboratory where artists, producers, and dramaturgs could do research and workshops to explore new ideas and learn about new approaches. This was really fun, but it was too much work and we were burned out after ten years, and so we stopped in 2015. AsiaNow productions became a starting point to build up an Asian producers network with Asian peers based on trust and friendship.

In Asia, we have long had this issue of how even very close neighbors may not know each other very well. Also, as I was saying, contemporary art tends to be Asian contemporary art as seen from Europe. It wasn’t just me, but an ongoing concern shared by many of my Asian industry peers, and before long I found an opportunity to build on this Asian contemporary art solidarity. Luckily, we were supported by public funding from Australia, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, and I was able to start APP as a way for Asian peers to rebuild their own perceptions of Asia.

- The APP Camp is held every year for approximately one week, with producers and other performing arts professionals coming together and holding a camp. Why did you devise it to be held in a style where each person participates in an individual capacity, separated from their background?

- I consider the philosophy of APP to be one of human connection. We camp for a week, we eat together, we talk, and that generates greater significance and results. It is about fostering organic mentorship among campers to learn from and about each other. You said yourself that you now have friends all over. By being together for a week, talking about what is really happening on the ground, you also get to hear people’s individual stories. It makes me think, camping is really great, isn’t it! [Laughs]

- That is so true. [Laughs] I participated in the first one, in Seoul in 2014. I shared a room with people from Taiwan, South Korea, and Australia, and we laid out our futons together, made breakfast together, and shared the same living space. The Taiwanese participant spoke the same level of broken English as I did, and as we did the daily work of laying out our futons and putting them away and so on, we stopped being self-conscious about our English and it ended up being a really good experience. You said, “Even if we want to do something together in Asia, until we increase our time spent together, we won’t be able to create shared values.” In everything you’ve done in the ten years since then, how much of your goal have you achieved?

- The impact of APP has been multifaceted. Above all, we were all able to talk to each other about issues faced by artists, like the state of our local creative industries and so on. Also, members coming from different countries shared information about what they were working on, and we were able to introduce touring shows from different places. The biggest impact was the way we were able to have deep interactions with each other as individuals. In other words, we made friends from all over the place. That was what we achieved with this. I think that’s what’s at the core of APP, so I plan to keep at it in this way.

-

Meeting held in Seoul in 2013 to prepare for the establishment of APP

-

The 2016 APP camps were held in Shizuoka and Tokyo, Japan

- What are your future goals?

- Places like Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Korea, and Australia have built up public institutions and mutual support systems, but Indonesia, Malaysia, Cambodia, and other countries in Southeast Asia do not have public support, and this is a real barrier to building up Asian solidarity. We want to strengthen ties even more in such areas. Even so, everyone has different systems and budgets, so it’s hard to think of all countries and regions equally. We need to find a way to connect us so everyone can contribute according to their own resources that they have, to the extent they are able. The issue we’ve been thinking about most recently is whether we should create a public organization like the IETM in Europe, or if we should remain a loose, informal organization. In particular, after the Covid-19 pandemic, what art can do, what sort of solidarity is possible, and what sort of organizational structure is best are increasingly important questions.

- In 2022, you became director of Korea’s largest international stage festival, the Seoul Performing Arts Festival.

- The festival began in 2001 and is held every October. We currently put on about twenty works every year, along with creative labs and workshops. At the workshops, participants can learn about artists’ creative processes and ideas, and also join discussions on contemporary discourse. We also have a creative lab project where the audience can observe the creative process in action and take part in the development of a work. For example, at the Sound & Technology Lab, we choose three domestic creators and first hold research workshops, then create pilot projects, and finally audiences that have seen those pilot projects share their feedback in the discussions. This process takes three years. Those are the three main components making up the current festival: staging plays, workshops, and creative labs.

- You don’t just showcase works; you also seem to really value connecting artists and audiences on an individual level. I feel like an opportunity like that would be a great experience for Japanese artists. How do you choose the works and artists for the festival?

- That’s the most difficult thing. The first thing I thought and questioned myself about as director was the meaning of the performing arts festival in this era. There are many other opportunities for audiences to encounter good works of all kinds, all the time. The aim of a festival should be to share a perspective on our era, reflecting on changes in social values with the audience. I brought up three curatorial directions: New Narratives, Innovation of Arts, Science & Technology and Posthumanism, and Locality & Translocality. Specifically, I focus on unheard or less heard voices. That would be women, people with disabilities, people from the LGBTQ community, and so on. Listening to many voices that have been quiet and sharing those voices with audiences. That’s the most important criterion. At the same time, I am developing accessibility programs to make an environment that allows people with disabilities to appreciate the shows.

Building new relationships between art and science-technology is another consideration when selecting works. After the pandemic, new challenges emerged in interrelationships between animals and humans, nature and humans, physical objects and humans. It’s an important issue in Korea as I’m sure it must be in Japan as well, to think about posthumanism and the role of technology in innovation.

About 50 percent of the festival is based on this curatorial direction. Of course, not every artist is creating with these themes in mind. The other 50 percent are chosen based on the works’ inspirations, questions, and audiences that the artists are trying to reach.

- Are non-Korean artists also considered?

- Half of the works at the festival are from Korea and others are international. Present audiences tend to take more of an interest in European works than Asian works, but as a festival held in Asia, it’s important for us to turn our gaze to the Asian region. From now on, I plan to be even more proactive about showcasing Asian works and artists than ever before.

-

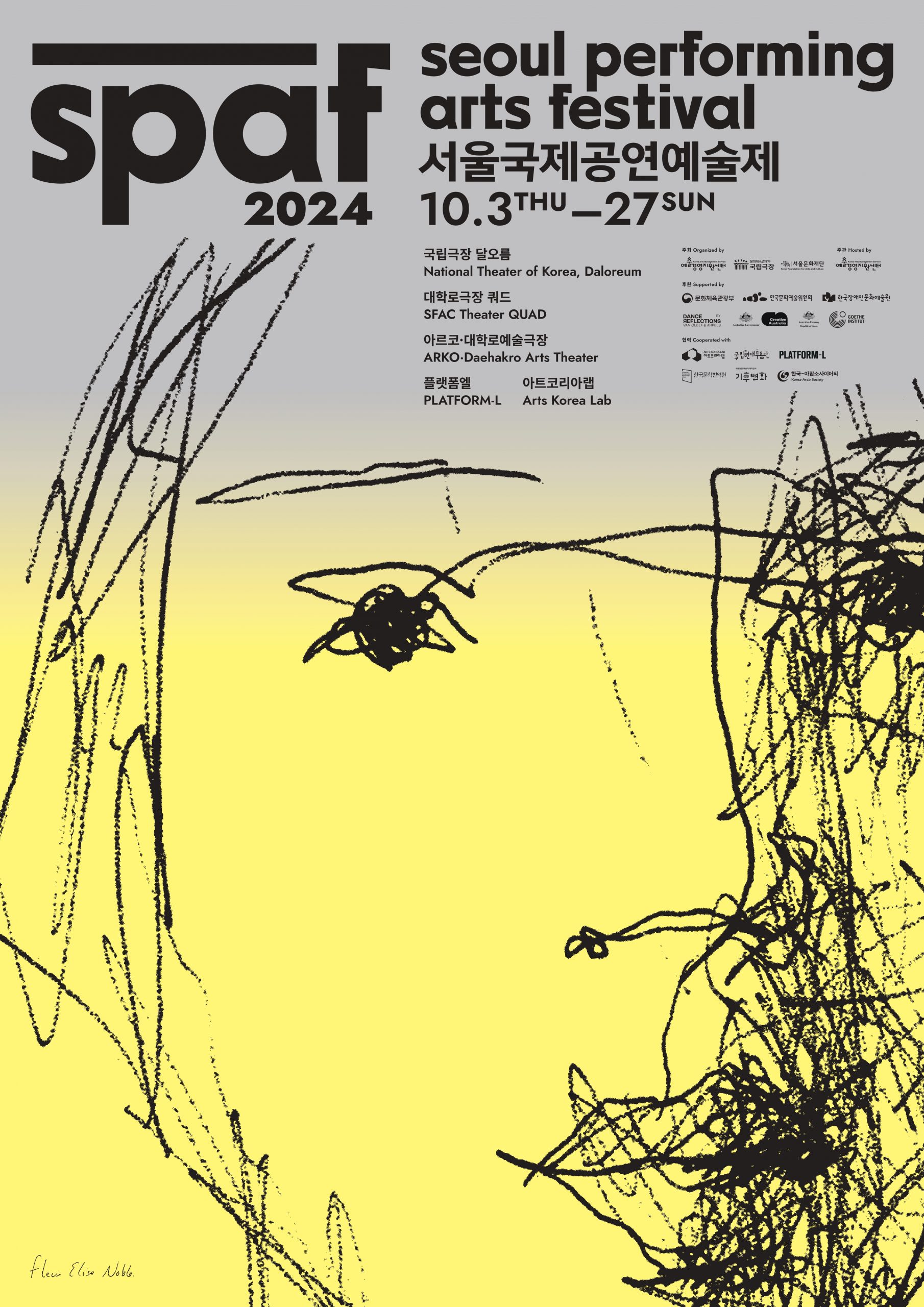

Poster from the Seoul Performing Arts Festival 2024 http://spaf.or.kr/2024/spaf/

- International performing arts festivals offer opportunities for people to travel, but in the past few years, especially since the pandemic, there are concerns about the environmental burden of air travel. I understand you’ve done research into green mobility. Have any positive proposals emerged?

- The title of that research is Next Mobility. As you said, the pandemic was a great crossroads. Next Mobility is not something new but we brought up three important questions. The first is concept touring. That means to tour not a work but a concept. For example, with the project in 2024, Australian choreographer Stephanie Lake first shares her choreographic view and method online to fifty Korean dancers. For actual rehearsals, there are two rehearsal directors who come to Korea, and Lake comes one week before the show. I also personally participate, and hold discussions on how the work can tour in different ways with fifty dancers, and even after the show ends, we hold a talk about what came up for us through the experience. That’s how it works. I’m planning on creating something with this method once a year.

The second is digital-physical hybrid mobility. It involves developing an app, holding research and discussions online, and then the actual creative work is carried out in person. In 2024, we will share one dance production, which will be presented as a live performance as well as in a VR version.

The third is green mobility. Rather than simply making works at a time of environmental crisis, we also have a technical rider for green mobility (covering the conditions and technologies necessary to stage the show), and while it is a tour, we work to reduce environmental damage along the way. For example, at our hotel accommodation, we ask them not to clean the room every day and just have the towels changed. If possible, the set is built locally rather than using international shipping. Also, through Asian festival networks and domestic partners, if we share the shows, we can minimize the carbon footprint generated by air travel.

- If you can build a network and people can get to know one another’s values, there’s a higher likelihood they can share their works. In this respect, Korea and Japan have had interactions since ancient times and this offers lots of potential, but along with that comes a certain difficulty due to our history.

- There are piles of unresolved historical issues between Japan and Korea, and even in artistic works there are things that can’t be avoided. But what should we do about it? Should we try to completely remove ourselves from it? Or should we tackle it head-on? I think that is for the artist to decide. When I came to Japan for the Yokohama International Performing Arts Meeting in 2023, I met Kaori Nishio and Satoko Ichihara. For the younger generation of artists like them, I got a sense that they are more interested in transcending nations than the issues between nations. For example, when thinking about the comfort women issue, naturally we cannot eliminate the political and historical perspectives, but in recent years, there is a tendency to emphasize the perspectives of women. Still, I can’t help but think that whatever theme they choose, artists must first engage in dialogue with the issues between nations. I really got a sense for the importance of making time for that. I’m planning a staged reading focusing on Asian playwrights for 2026 under the title of “Asia and Asian Diaspora.” It’ll feature playwrights and directors from Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, Korea, Australia, and New Zealand, coming together and thinking about what they can bring to Asia. For example, what are Japan and Korea’s positions as seen from the rest of Asia? I’m thinking it will be a good time to hold those discussions.

- If you look at the history of performing arts coming from Europe, Korea was influenced by European-style theater via Japan, or so they say, but if you go back even further, Japan has been influenced by the performing arts of the Korean Peninsula for more than a thousand years, so from the perspective of a history of performing arts within Asia, it would be great if the two countries could rebuild that relationship.

- I feel the same way. We know a few things about European playwrights, but for example, when it comes to Asian playwrights, we are inevitably hindered by barriers of interest and information, and as a result we don’t know much about them. In that way, people like us who hold international performing arts festivals in Asia have a big responsibility. During my term as director of SPAF, I’ll do my best to make this situation a little bit better.

-

Photo: Leo Yamamoto

Interpretation: Hong Myunghwa

Related Tags