Saori Hala

The Potential of Saori Hala: Inspired to Pursue Dance by a Great Earthquake

Photo: Kikuko Usuyama

Photo: Kikuko Usuyama

Saori Hala

Dancer, choreographer, and visual artist Saori Hala is based in multiple cities including Tokyo, Yokohama, and Berlin. She creates performances and choreographed works exploring space, the body, and physical attributes. Da Dad Dada is a self-documentary performance about her father who was also a dancer and about her separation from him in life as well as in death. It was performed in Japan and Germany, and restaged in 2021 at Japan’s largest dance festival, Dance New Air. In 2020, she won the 9th El Sur Foundation New Talent Award for Contemporary Dance. Hala has master’s degrees in design from Tokyo University of the Arts, and in solo dance performance from Berlin University of the Arts. She is currently a Dance Base Yokohama Resident Artist. (Updated May 2024)

Saori Hala skillfully and precisely commands a range of mediums with her intelligent compositional abilities, sharp movements, and clear narrative voice. Originally from the design world, she found a creative outlet in the performing arts. Hala’s ideas and bearing are unique, a departure from the classic image of a dancer or choreographer. She moves between Germany and Japan, collaborating with artists and creators from different fields. In 2023, she acted in the German stage adaptation of Mieko Kawakami’s Breasts and Eggs at the famous Thalia Theater, directed by Christopher Rüping. This experience, she says, contributed to her decision to return to Japan, where she is now based. Eri Karatsu, director of Aichi Prefectural Art Theater and artistic director of Dance Base Yokohama (DaBY), recognized Hala’s potential at an early stage. She interviewed Hala to explore the full picture of this artist of boundless magnetism.

Interview: Eri Karatsu

Text: Kenta Yamazaki

English Translation: Claire Tanaka

- The first time I saw you dance was in 2016 in Nagoya at the Spazio Rita art space. The way you placed your body in the space was very different than the other dancers, and my first impression was that you used your body almost like an object. When I found out later that you had studied design in university, it all made sense to me. Why did you choose to pursue dance after studying design?

- When I was small, I studied ballet, but I realized the basic technique side was something I’d never to be able to do professionally, so I quit at age eleven. The reason I pursued design was because I liked graphics, and even when I was doing ballet, I preferred creating things over dancing. During my barre lessons I always fantasized about things like corps formations and stage sets. At that time, I didn’t know there was a profession called choreographer, so I figured my love of thinking about placement and light meant I should pursue design. When I was eighteen, I would work hard and get into the top art school and then work my way up at an advertising agency for ten years, and when I set out on my own I would do art direction at a theater and do it all myself, the set and everything … or that was my plan, at any rate. I like creating the overall concept for a piece. I find it embarrassing to be the dancer in the center of something, so in that sense I didn’t think I was suited to being a dancer.

I got into the Department of Design at Tokyo University of the Arts, but just as I was graduating, the Great East Japan Earthquake happened and the graduation ceremony and exhibition were all canceled. To an art school student, the graduation exhibition is an important part of finding a job after you leave college. It’s an opportunity to make your debut in society, so to speak. Everyone had been betting on that, but it got canceled without any clear reason due to the pressure at the time to show “self-restraint” out of respect for the victims of the disaster. I felt like society had confronted me with this assumption that art was useless, and I was shocked to see how an entire society could operate based on emotions and mood. It was also a shock to realize that Japan has always been this way. Part of being a designer or working at an advertising agency is about creating a social mood, so I thought that I wouldn’t be able to stand doing design work in such a society.

Because of this feeling that my trust relationship with society had been destroyed, my daily life was also ruined, and yet my desire to do art wasn’t diminished at all. In this way I began working toward a sort of dance I could do with my own body alone. In my own way as a student, I’d been thinking seriously about design that helps society and I was suddenly excluded like this, so I started over with just my own agency, and decided it was healthier to take the approach of thinking, “it doesn’t have to mean anything, I’m doing it by myself after all.” It wasn’t as though I was motivated to express something physically with my body, but rather I decided that dance was a way for me to do something without having to depend on anyone else.

- After that, you started graduate studies in design at Tokyo University of the Arts and immediately went on exchange to Germany. Why Germany?

- First of all, I wanted to shift from design to dance, and there was no option for that in Japan. My supervisor for my graduate program in the Department of Design, Professor Keiichiro Fujisaki, also suggested that I consider going overseas, but at that time I didn’t have any overseas connections or funds. My only opportunity was the exchange student system. So I went to study at Bauhaus University in Weimar. The first time I saw a specific piece that connected design with physical bodies was a video work by Oskar Schlemmer, a member of Bauhaus, called Triadisches Ballett. Bauhaus does a lot of scenography, so when I found Bauhaus on the list of places available for exchange, I thought this was the only one for me. That’s where I went on exchange, but before that I spent three months in Berlin, which was very significant. When I was getting ready to go, I happened to meet Akane Nakamura of precog and she said, “I’ll connect you with a shared residence in Berlin, so why don’t you go early?” In Berlin, I went to dance shows every day at a lot of different theaters, and I felt like the dance I had been wanting to see was all there. That’s where I went on exchange, but before that I spent three months in Berlin, which was very significant. When I was getting ready to go, I happened to meet Akane Nakamura of precog and she said, “I’ll connect you with a shared residence in Berlin, so why don’t you go early?” In Berlin, I went to dance shows every day at a lot of different theaters, and I felt like the dance I had been wanting to see was all there.

Even after I started at Bauhaus University, I would go to Berlin on the weekends to hang out and watch shows, and I lived that life for a year. Bauhaus University is an architecture school after all, and Weimar itself is a very small town, so it didn’t have many alternative dance performances. In Berlin, there are lots of lectures and workshops for freelance dancers, and it’s an environment where you can learn theory and practice pretty deeply. After that, I entered graduate school in Berlin, but I was already participating in such programs, and the people I met gave me advice about which theaters were good, and told me that I should go to grad school if I wanted to make a living as a dancer. That was where I really learned that there is information you can only access once you’re a part of the community as a dancer.

I took a leave of absence from my grad school in Japan in 2012 in order to go on exchange, but since universities overseas start from September, I had to take a two-year break in order to do a full academic year overseas. I had extra time, so after my year abroad I applied to a residency program and went for another short stay in Berlin. At that time, I was still just getting started, and although I had danced a bit and done some sessions, I hadn’t even made three original works and I didn’t even really have a sense of my own identity as an artist.

- In 2014, you finished your exchange and in March 2015 you completed your master’s degree in design at Tokyo University of the Arts and then back to Germany yet again, this time to enter graduate school at Berlin University of the Arts. What inspired you to go to grad school again?

- I was really affected by a work I saw at a theater in Berlin called Sophiensaele, by a female Korean artist named Lim Jee-Ae.1 The way she uses scenography, her way of relating objects and bodies, I was moved by that format. “It’s alright to call this dance!” I thought. When I read about her career, I found that she had studied solo performance at Berlin University of the Arts’ dance faculty. At that time, I was still on leave from Tokyo University of the Arts, so before I went back to Japan I decided I would return and study at Berlin University of the Arts.

-

Lim Jee-Ae

Lim Jee-Ae is a dancer and choreographer. After dancing with both traditional Korean and contemporary dance companies, she relocated to Germany, and currently lives and works in Berlin. Reference: https://performingarts.jpf.go.jp/en/article/6729/

- Of everything you learned at Berlin University of the Arts, what stays with you most to this day?

- Putting things into words. The biggest official goal of the program is contextualizing. We had a class on shaping our artist statements. It’s the dance faculty, but we didn’t have a place to dance, and in two years I didn’t have a single physical class. At that time, I was the youngest in my program at twenty-six. A lot of people join the program after working professionally for ten or fifteen years, so perhaps dance itself went without saying. I think a lot of people used it to figure out the possibilities within what they’d been doing, and to think about how to position themselves in the market.

Of the eight people, only two were German. I got the impression that they tried to balance the number of people from inside and outside Europe. Everyone had some kind of skill other than dance. There was an actor who used to be a doctor doing solo performance inspired by medicine, and another person was of Russian and Chinese descent who did dance-based gender performance. People would pursue their own possibilities with their whole identities. That was where I, too, found renewed understanding in working with design and dance.

We had times where the eight of us would take turns analyzing each other. One person would give an hour-long presentation, then everyone would discuss it for another hour, and we kept on at that for the two years. I learned that ways of thinking and how to make leaps in research are skills that can be acquired by training, and I started looking at the other artist statements to see what they were saying about their work. I was already so inclined, but that was how I learned to think of using words as part of creating.

- Is that how you made your first work, Da Dad Dada?

- Yes. I spent a year making Da Dad Dada for my final grad school project. It started with a very personal motivation, which was that I felt like I couldn’t move forward until I made a documentary theater work about my father, who had been a dancer in musicals. But I was not allowed to do something simply because I wanted to. I made works in progress several times, and I kept on butting up against the question of how to make it socially relevant. I was an Asian female dancer in a Western society, and I had to think about what it meant for me to make a work about my father who had been a dancer in musicals, which were part of the American culture that came to Japan after the war. I had no way of getting anyone to listen to this, so I just kept at it by myself, and eventually finished the piece.

Participating in that program in Germany has definitely become the basis for who I am today, but at the same time, I was always thinking about how great it would be if I could do it in Japanese instead of English. So after coming back to Japan, I created a platform where artists could critique one another like I had been doing in Germany. At Festival/Tokyo 2019, I began doing a research and development program called Artist Pit, and the following year, I began a project called PORT: Performance or Theory with another artist who had participated in Artist Pit, and I continue to do that.

-

Da Dad Dada. Photo: Yulia Skogoreva

- Your work has a strong element of being a producer that creates a situation, doesn’t it? You’re personally pioneering this approach of overlapping the environment you need to live with and the social circumstances you think should exist.

In 2018, when I saw Da Dad Dada, it had a bird’s-eye view while you were also in the center as a performer. As a work, it was incredibly private while also skillfully connected to the wider topic of the Tokyo Olympics, all done by yourself alone as a young woman in her twenties, and that surprised me. I thought that perspective was what is lacking in artists in Japan these days. Did you have any feelings of wanting to change the situation in Japan when you decided to stage it here? - I really felt like if I didn’t check once how this work and myself as an artist was received in Japan, I wouldn’t be able to move on to the next thing. There were parts that referenced the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, so I felt like I should put it on before the 2021 Games. But I wasn’t thinking at all about how I wanted it to connect with what I would do next. I hardly had any dance connections in Japan, and I think a lot of the people who came to see it were more the kinds of people who like pop culture or subcultures. I am from a design background, so I thought I would be able to get better feedback from art- or design-related people than from dance people, so I sent the publicity for the show to those sorts of media outlets.

- After you graduated, you were active as an artist while moving back and forth between Germany and Japan. Why did you now choose to return permanently to Japan?

- More than anything, it was the language issue. Living as a foreigner, I always felt that the work of deepening my ideas was unconsciously stoppered due to language. I think I started to feel the limits of thinking within a range that always has to be aware of translation. Of course, Japan’s performing arts isn’t as institutionally sophisticated as Germany’s, which is one issue, but even so, I thought it was necessary for me now to create an environment where I can dive into my thoughts alone. That’s why I decided to place a definitive distance between myself and Western society.

But one trigger could have been when I was participating in the creation of a new repertory work for the Thalia Theater in Hamburg. Mieko Kawakami’s novel Breasts and Eggs had been a hit in Germany, and a German theater work based on the book was being made. The rehearsals and performances involved such a wonderful team, it was so inspiring it brought a tear to my eye, but even at this top level, I felt there was something wrong about how Asian culture is portrayed in Western culture. Of course, it’s common to change things from the original work, and I was told that the goal is not for the director to correctly convey every word and phrase from the source text. Above all, what matters is that Western people can understand it. You might call it “advanced cultural translation,” but I thought that the longer I continued to work in Germany, the bigger this sense of discomfort would get. Both my joy and my doubts vis-à-vis my creative output had peaked. I started to think I should draw a line in the sand, and that my feelings were steering me toward returning to my country of birth.

-

Breasts and Eggs (based on the novel by Mieko Kawakami and directed by Christopher Rüping), performed at the Thalia Theater in Hamburg as part of the 2022–23 season. Hala is in the center, and to the right is Maike Knirsh in the role of Natsuko. Photo: Krafft Angerer

- Now you have returned to Japan, what is the first thing you want to make?

- First, I want to focus on thinking about words, bodies, and dance. By that I don’t mean just standing on a stage and talking, but it could also mean notes about creating a new work, or communication with dancers. I have more opportunities to write standalone texts lately so I want to think about the technical skill of writing.

I’ve also been thinking a lot lately about humor. I saw a performance in Germany that was humorous and used language, but also had elements of dance, and that really spoke to me. But doing something like that in Japan always comes across as sort of alternative. I’ve been thinking about whether it has to be that way, and I want to do it right. It could be context, political elements, or concepts; there are many ways to do it. I don’t want to make something that gets audiences slapping their thighs or smirking, but I do want to make proper humor that is intellectual.

- You come off as clever and intellectual, but you also have a cute and poppy side. I think that came out in the show you put on with composer Tomomi Oda in 2014, P and Re. You’ve collaborated with a lot of other musicians as well. Could you speak about the relationship between music and dance or the body?

- I actually have barely had any experiences working deeply with musicians beyond doing sessions. Yoshio Otani2 might be the only one. Otani participated in Artist Pit, and he watches rehearsals and gives me advice. Influence-wise, another person who has made a big impact on me is Fuyuki Yamakawa.3 Yamakawa does music sessions, stage works, acting, and installations. You don’t see many people like that in Japan, using their own body as a medium, and also creating with text. He’s someone I look up to and who showed me how to pursue an alternative practice.

-

Yoshio Otani

Yoshio Otani is a musician and critic. In addition to his jazz session work with a range of bands and musicians, he also contributes to plays and dance performances by the likes of chelfitsch and Tokyo Deathlock.

-

Fuyuki Yamakawa

Fuyuki Yamakawa is a visual artist and khoomei singer. He uses his own voice and body as a medium for unique and diverse expression. Reference: https://performingarts.jpf.go.jp/article/6924/

- Speaking of working together with others, you appeared in Midori Kurata’s Please applause when the conductor appears in 2023.

- That was my first guest appearance in Japan. It wasn’t a collaboration; I just appeared in Kurata’s work. I spell my name in katakana in my work, and that’s my way of objectifying my own self and my own body, but Kurata told me that I can be Hara Saori—the version of me written with my full kanji name—onstage. Saori Hala could do the performance by herself, but she said wanted me to be my “old ugly self.” It’s like she said she was going to expose me. But since that was a realm I couldn’t enter alone, I thought I’d hand over the material that is myself to her.

-

Please applause when the conductor appears by Midori Kurata. Hala is at rear center. Saitama Triennale, November 2023. Photo: Ryuichi Maruo

- Do you see yourself using your experiences guesting in Breasts and Eggs and Please applause when the conductor appears in the future?

- I had already begun to feel my limits, as being both director and performer has too high of a cost. I wanted to find out what it felt like to just perform, so I agreed to do the guest performances. In the end, I realized I can’t separate my urge to make things and my urge to perform [laughs], so by trying out guest performing, I’m now really having fun thinking about the dividing line between performance and choreography/directing/dance/execution. In March, I put on a work in Kobe called The Iron Ball for the 8 Months Residency Program’s final performances, and I treated it as a work in progress for me to think about those things. It won’t happen for a while, but at the end of November I will be debuting a piece with Kaho Kogure as a duo at the Aichi Prefectural Art Theater, and we have decided to divide the work so Kogure does the choreography, and I do the directing, writing, and concept.

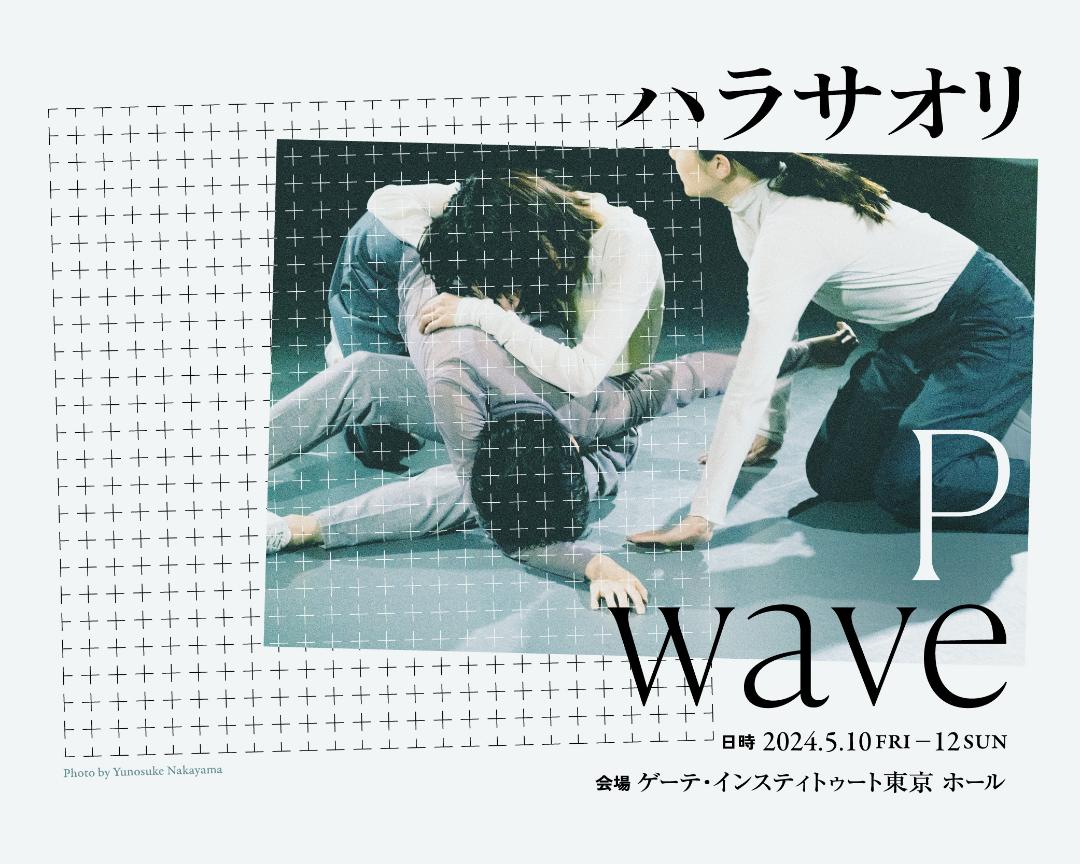

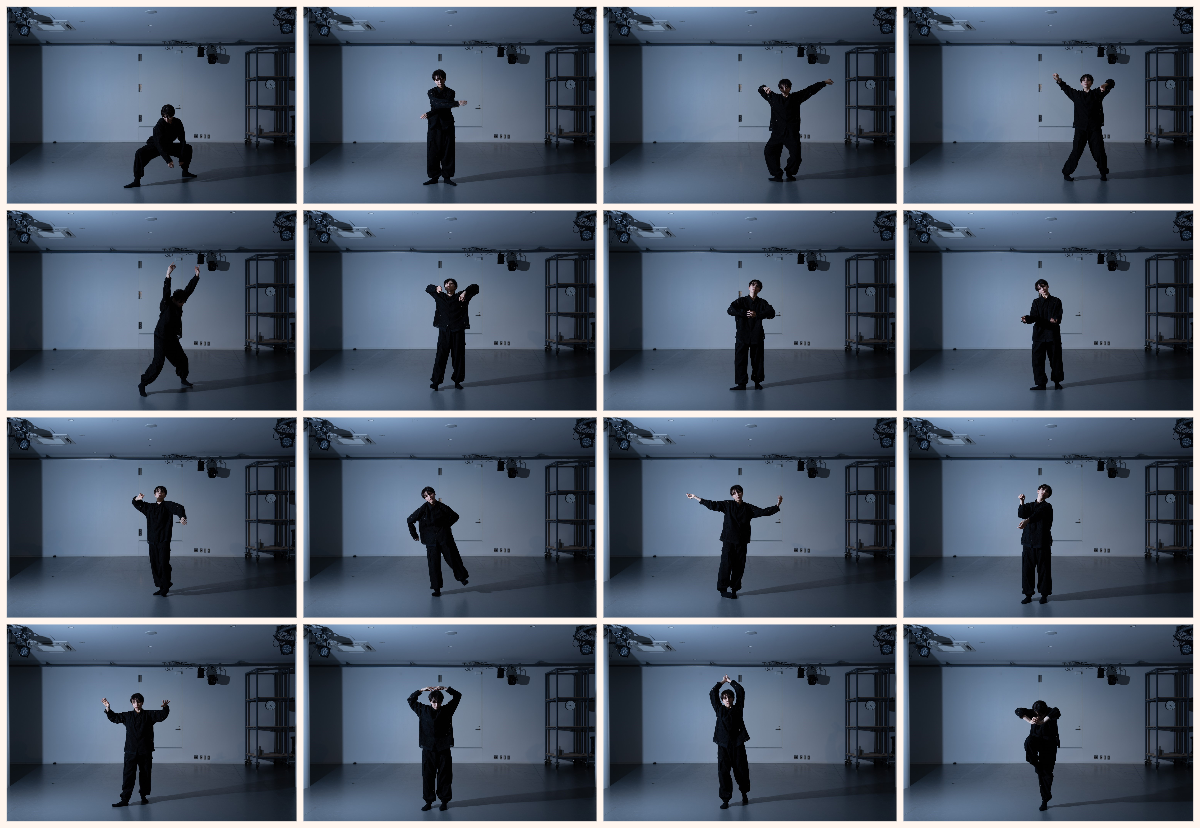

- This new work and several others are going to form a repertory at DaBY Performing Arts Selection, a collaboration between DaBY4 and Aichi Prefectural Art Theatre. I’m also preparing to bring it to the Kanto area in December. The two of you both put on a lot of solo works, so I think appearing onstage alone forms the basis of most of your work, but the way you approach it is totally different. Comparing that sort of thing will be an interesting part of this, which is why I proposed you work together as a duo. P wave will be staged in May, which is a piece you performed as a work in progress at DaBY in 2021.

- “P wave” is an abbreviation of “primary wave” and refers to a preliminary tremor. This work derives from my experiences of earthquakes. Like I explained earlier, the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake changed my life, something I’m strongly aware of, but when I look back, I’ve been affected by earthquakes ever since I was small. I’m interested in the sort of passive body that accepts and dodges. In both design and dance, I had a strong interest in the body subject to affordances, and how to adapt to the environment.

But when I tried to pursue themes like that, if I wanted to do it in the West, I found I needed to employ a range of tricks. The impression of passivity there is somewhat negative. And even when it wasn’t, I still felt like I faced pushback, as if the immediate response was: “That’s so Eastern.” Even when speaking to a German dramaturge, I was told if I as a woman were to speak of passivity I had to connect it to feminism, or to a context of immigration. The context of someone who has been pushed out and arrived where they are. If it isn’t given that political angle, there isn’t enough of a hook. That is interesting in its own right, but I feel like operating under those assumptions means I’m not able to deepen my thoughts. Since Germans have never experienced earthquakes, there is a certain hurdle I need to clear there.

Meanwhile, performing in Japan, if I incorporate the sorts of conversations you’d have when an earthquake comes—like asking each other, “Are we shaking?”—people recognize it immediately. When I did the work in progress, I spontaneously hit on that and felt the work immediately get deeper, and that was fun. For example, in the alertness I have to sensing preliminary tremors, I can feel how my physicality is connected to my Japanese background. Emergency drills are ultimately a sort of choreography, right? In that sense, I am now realizing that I wanted more time to think freely.

This time, since I’m able to create and put it on in Japan, I think I might divert a bit from the earthquake topic and explore some slightly larger thematic possibilities.

-

Previously staged as a work in progress, P wave premieres May 10–12, 2024. Contact: Co.S (co.saorihala@gmail.com)

- By going back and forth between Japan and Germany, I felt that your way of seeing the good sides and issues of each place has been enhanced to a higher resolution. I hope that through communities like DaBY, you’ll involve creators from other fields and lead and inspire Japanese dance artists.

-

DaBY

Dance Base Yokohama (DaBY, pronounced “day-bee”) opened in Bashamichi, Yokohama, in 2020. With a focus on programs for nurturing artistic talent and developing the professional dance scene, DaBY aims to be a center bringing together dancers, creators, critics, audiences, and more. https://dancebase.yokohama/en

-

Interviewer Eri Karatsu

Special thanks to Dance Base Yokohama -

Photo: Kikuko Usuyama

Related Tags