The Unnameable Dance

Written and Directed by Isshin Inudo

© 2021 The Unnameable Dance Production Committee

https://happinet-phantom.com/unnameable-dance/

Min Tanaka

“I dance not in the place I dance the place”

The Unnameable Dance of Min Tanaka

(C) Madada Inc./Rin Ishihara

Min Tanaka

Min Tanaka was born on the day of the Great Tokyo Air Raid, on March 10, 1945. He grew up in the near-by semi-rural town of Hachioji at the western edge of greater Tokyo. He was said to be “a quiet child” who liked playing alone, and eventually he became absorbed in a number of traditional Japanese performing art forms such as Bon-odori (Bon festival dance), Kagura (sacred Shinto music and dance), Naniwa-bushi (narrative ballads recited to shamisen accompaniment), Kawara-shibai (popular theater in the Kyoto area) and Mikawa-manzai comic plays. In his teens, he loved reading Japanese literature, and also became absorbed in Surrealism. Later, his admiration for the performance of the Japanese Olympic basketball team led him to enter the Tokyo University of Education (currently University of Tsukuba), but finally giving up on basketball, we began studying classical ballet and modern dance.

From 1966 Tanaka began performing solo dance pieces. He began doing numerous performances (action) in a variety of places, and in 1974 he chose to use “the naked human body as costume.” During this period, he met Kazue Kobata and Seigo Matsuoka, who would become fellow associates. In 1978, he borrowed the term “body weather” that emerged from his dealings with Matsuoka and founded the Body Weather Laboratory in Hachioji. That same year, Tanaka was invited to participate in the production Time and Space of Japan – Ma planned and produced by composer Toru Takemitsu and architect Arata Isozaki in Paris, where he performed his dances for three weeks. This led to many new opportunities for exchanges that made “Tanaka the nude dancer” widely known among intellectuals and performing arts fans in Europe and North America, while also leading to performance activities in many other countries.

In 1981, he formed the dance company “Maijuku” (dissolved in 1997). In 1982, he founded “plan-B” in the Nakano district of Tokyo, where not only his own performances were held but also a wide variety of other events, ranging artistic storytelling, symposiums, talks, live music concerts, exhibitions, film screenings to theater and dance performances. Before its opening, Tanaka wrote a homage to Tatsumi Hijikata titled Chi wo Hau Zenei (literally: An avant-garde crawling on the ground) for the magazine Yu. As a further development from this, Tanaka asked Hijikata to choreograph the piece Ren-ai Butoh-ha (Love-Dance School – the original title) which he subsequently performed.

In 1985, Tanaka moved to the village of Hakushu in Yamanashi Prefecture. There, he established the Body Weather Farm (Shintai Kisho Nojo) where he engaged in dance and farming. From 1988, Tanaka organized an outdoor arts festival in Hakushu, which provided artists from Japan and abroad a venue to present their works or work in creative collaborations (In 1997, in the same location he established The Dance Resources on Earth (Buyo Shigen Kenkyu-jo) with the aim of gathering research material concerning Japanese folk arts, traditional performing arts and folk [performing] arts from around the world.

In 2002, Tanaka appeared in the movie Twilight Samurai (Tasogare Seibei) directed by Yoji Yamada. After that, he drew attention as an actor in movies and TV dramas, although dance remained his “main occupation.” In 2004, after traveling around the islands of Indonesia and doing dance performances for 45 days, Tanaka began performing improvisational dance in various everyday places under the Locus Focus project (Ba-odori: a site-specific and improvisational dance performance).

For years after that, Tanaka formed relationships and worked with many artists and philosophers, including musicians Cecil Taylor, Derek Bailey, Milford Graves, Lajko Felix, Tajiana Grindenko, Vladimir Martynov, Seiji Ozawa, Yosuke Yamashita, Yuji Takahashi, Keiji Haino, Yoshihide Otomo, Ryuichi Sakamoto and philosopher and author Michel Foucault, Felix Guattari, Roland Barthes, Susan Sontag, Kenji Nakagami, Toru Terada and artists Richard Serra, Karel Appel, Jean Kalman, Noriyuki Haraguchi, Fujiko Nakaya and others.

From January 2020, Tanaka started a series of solo performances aimed at “Creating place dance full of pre-verbal sensibilities” at Theater E9 Kyoto. In December of the same year Tanaka joined with Seigo Matsuoka to present a theater performance titled Yo! Don Quixote at the Tokyo Metropolitan Theater. Then, in January 2022, a documentary film on Min Tanaka titled The Unnameable Dance, was released. This documentary was made possible through a continued relationship with the film director Isshin Inudo, which ensued from Tanaka’s appearance in the film La Maison de Himiko (House of Himiko), and it was the result of material gathered over a period from August 2017 to November 2019.

Interviewer: Tetsuya Ozaki (Chief Editor of the ICA Kyoto publication REALKYOTO FORUM)

- You were born on the day of the Great Tokyo Air Raid in March 10, 1945. In the recently released documentary film The Unnameable Dance, there was reference to this and other facts about your upbringing as well as documenting of your Locus Focus project from August 2017 to November 2019, your life in the rural villages in Yamanashi Prefecture and more. There are so many things that I would like to ask you about, such as your upbringing, your encounter with Tatsumi Hijikata that had such a profound effect on you, about your relationships with figures like Roger Caillois who coined the name “unnameable dance,” and Colin Wilson, the author of Outsider, author and filmmaker Susan Sontag, the artist Richard Serra and others.

Among all this, I would like to begin by focusing on the period from the 1980s until the present when you have continued to perform improvisational “Locus Focus” (Ba-odori) in such a variety of locations. In the 1980s, you were also one of the co-founders of the experimental space plan-B (Nakano, Tokyo) (https://i10x.com/planb/about) where, in addition to dance, cutting-edge works in literature, architecture, the fine arts, music film and more were presented. Could I ask you to begin by telling us about plan-B. Was it your proposal that started it? - I told Kazue Kobata (art producer, translator, emeritus professor of the Intermedia Art Dept. of the Faculty of Fine Arts of Tokyo University of the Arts) my idea of what I wanted to do and asked for her opinions about how best to achieve it. I was very keen on making it a joint venture with a number of people, so we ended up gathering people from a wide variety of genres to launch it. It started with a lot of momentum, a lot of people joined in the discussion, like Tetsuji Takechi (director and critic known for Takechi Kabuki) in theater, and in the music field it was the same. I did my series called “Present Dance” (Genzai no Odori), and we got a lot of people to come, from Butoh and other fields, and I left it all up to them to do what they wanted. That continued for about two years, I think.”

- Plan-B opened in 1982, but the previous year you also started “MMD plan” with percussionist Milford Graves and guitarist Derek Bailey.

- When they first came to Japan (Milford Graves in 1977, Derek Bailey in ’78), they were performing at Seibu Theater, the predecessor of today’s PARCO Theatre. I went to hear them and was really surprised by their performance. When Seigo Matsuoka (chief editor of the Magazine “Yu”) interviewed Milford, I was standing by listening to them, and they said that after that they were going to Hachioji to do a performance with Kaoru Abe (saxophonist) and others. Since I’m from Hachioji, I offered to take them there, so we got on the Keio Line train to Hachioji and then the live performance club where they were to perform. There we found a gathering of a bunch of musicians who wanted to play with Gilford.

- That was at the invitation of the “free jazz” critic Akira Aida. He is the one sparked the free jazz boom at the time, because he was the first one to introduce free jazz to Japan.

- Yes. It was Akira Aida. And it was by talking with him that I first connected with musicians like Toshiyuki Tsuchitori (percussionist) and Toshinori Kondo (trumpeter). Aida-san appreciated my work in performance and that is why, after the “Time and Space of Japan – Ma” in Paris (an exhibition planned and directed by Toru Takemitsu (composer) and Arata Isozaki (architect and thinker) in 1978), I went with Derek Bailey to London in 1979 and did a duo performance with him for the first time. After that, I went with Derek to New York to perform at The Kitchen performance space, and at that time I invited Derek to come with me to Milford Graves’ place. That was the first time that the three of us got together.

- So, you were the one that got Milford Graves and Derek Bailey together?

- Yes, that’s right. And right away, that led to us performing together in Japan. But it wasn’t easy. Because, in the world of music, having two such important musicians with such different styles performing together just wasn’t done normally. But it turned out to be a great success. Huge crowds turned out wherever we went to perform in Japan.

Establishing plan-B and the pursuit of improvisation

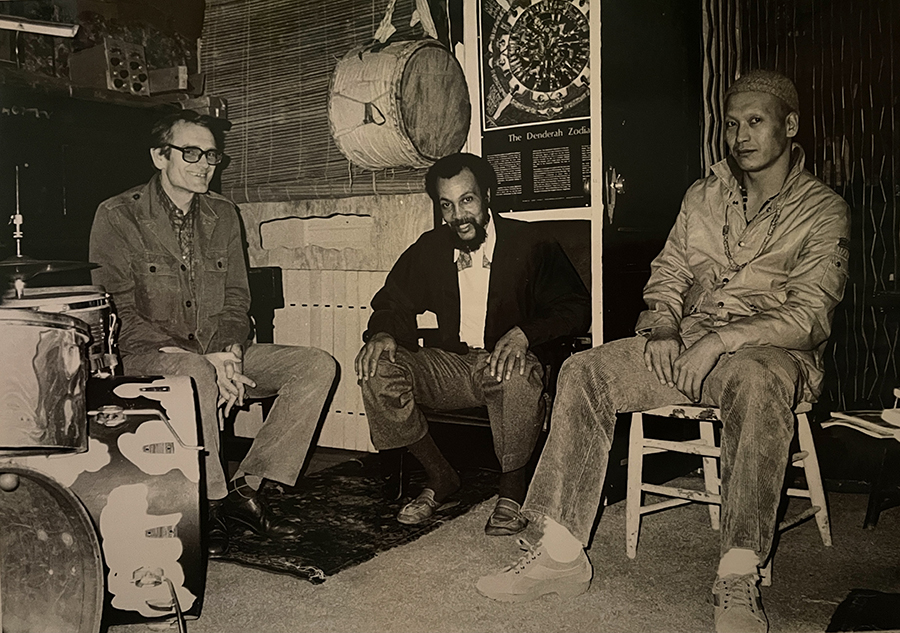

Photo of Derek Bailey and Milford Graves when they first met.

(from left) Bailey, Graves, Tanaka

- At the time, was it common to have free jazz or improvisation musicians to perform together in improvisational collaborations with dancers?

- No, it wasn’t common. We also use the word “improvisation” in dance, but I personally divided it into improvisation and ad-lib dance. My ad-lib performance is where I take things in my storehouse and work with them in changing combinations. Because the same movements will take on a different appearance when the space changes. Things also change rapidly as the distance from the walls change, and even if the movements of the dance don’t change, the way it appears will change if you do it in the middle of the desert compared to doing the same movement in a forest.

But improvisation means doing things (dance) you have never done before, so it is a completely different thing. It can’t be done solely with the things that you already have within you. - So, that is why you need the mutual input that comes in a collaboration, right?

- Derek says, “I want to see clouds I have never seen before. That is improvisation,” while Milford describes it as, “Constant revolution without a moment of rest.” Musicians like Yoshihide Otomo (guitarist, turntable player) and Keiji Haino (experimental musician) have all seen MMD performances. And both Milford and Derek had performed for us at plan-B.

While Milford is also a musician who powers ahead full strength, I later met someone who was even more amazing, and that was Cecil Taylor (poet and pianist). Before he passed away, he took part in the “Cecil Taylor – exhibition” at Whitney Museum of Art at which I alone participated as dancer. And in front of an all-white audience, during gaps in the piano playing, he delivered the lines: “There was a time when people with earth-colored skin were bought with money and moved out of Africa to places around the world. Isn’t that something more terrible than war?” Those words were posed to the audience as a type of “poem” in his unique style! - Cecil Taylor received the Kyoto Prize in 2013. You performed together with him as a duo at the performance commemorating that award.

- Because it was an awards ceremony, there were other people giving lectures introducing the results, but Taylor read a poem in a hoarse voice and I came out and together we did an improvisational performance. I was contacted by the person in charge from the sponsoring Inamori Foundation. I remember them telling me that Cecil was going to receive the Kyoto Prize, and at the ceremony, rather than giving an acceptance speech, he said he wanted to play the piano and to do a performance with you. And they asked me very politely if I would accept his offer. It was normal for award winners to go up on stage with their families or relatives to receive the award, but since he didn’t have any family, he wanted me to go out on stage with him. I replied that I really wanted to congratulate Cecil, and so it was purely out of respect for his presence that I humbly agreed to performed with him.

- In the same year that you started plan-B, you had the text Chi wo Hau Zenei (literally: Avant-garde crawling on the ground) published in the magazine Yu. It was a text that was essentially an homage to Tatsumi Hijikata.

- We didn’t start plan-B until after that was published. Our plan-B venue was located on the basement floor and above that on the ground floor was a place called The Shop, where we could all gather to drink and talk after the performances at plan-B. It was Nario Goda (dance critic) who brought Hijikata to the plan-B performance. I was down in the dressing room when Goda-san came down and told me, “Hijikata is here.” I was trembling so much that I danced terribly that time. When afterwards we met up at The Shop, Goda-san told Hijikata that my dance that day had been terrible [because I was so nervous], and in response to that Hijikata-san said, “Who can dance [in front of an audience] without getting nervous?” I was so surprised. That was the first time that he had ever spoken directly to me.

In 1977, I was doing a project titled Hyper dance 1824 hours, in which I danced in places all around Japan. I would make a call and leave a message on the answering phone stating when and where I would start to dance and then just start my improvisational dance performance [in a public space] without getting anyone’s permission. As the final performance of that project, I danced in front of the Aoyama Tower Hall [which no longer exists] in Tokyo. That was the year that Taruho Inagaki (writer) and Hoei Nojiri (essayist, astronomer) passed away, so in part it was an homage in mourning to them. Hijikata-san had been watching that performance, and as soon as it was over, he came up to me and said, “There is a gap between your fingers, isn’t there? Try practicing with something like a pair of chopsticks between your fingers.” He was probably saying that because he saw a habit of mine that even I hadn’t notice before.

Around that time, Hijikata-san had completely disappeared from the dance world. That was just before we started MMD in 1981, and at the time I was looking for friends to join me in forming a “Maijuku” (dance studio/school). I got up my courage and took the liberty of calling Hijikata-san’s studio. I wanted to encourage him to start dancing again. When I called, the person who answered the phone was definitely Hijikata-san, but in a raspy voice he said, “The master (Hijikata) has gone back to Akita [his native prefecture in the far north]. But I just couldn’t bring myself to say, “It’s you, Hijikata-san, isn’t it?” (Laughs) So, instead I said, “Well, please give my regards to him anyway. Thank you.” And then I hung up, but I’m certain that he must have known it was me. - That is fascinating, isn’t it?

- It certainly was. After he saw me dance at plan-B he invited me to go with him to have a drink in Roppongi, so we got three taxis to go there together with members of our dance studio at the time. When we got to Roppongi, he was the first to get out of the lead taxi, and then he started scattering bills [money] about. And he did it while doing a dance!

- What was the performance Hijikata had seen you dance in?

- It was part of a series called Emotions.

- What made you decide to title it Emotions?

- Before that, I had done what I called Hyper dance, or Butai [combining the characters for “dance” and “fluttering,” as in the fluttering of flower petals as they dance on the wind that scatters them]. And because I liked the concept of “drive” as science fiction writer James Graham Ballard used it, when I was going out to do a dance, I would say, “I’m going for a drive” (laughs). Then I started a dance studio/school (juku) where I would meet with about 50 young dancers every day for about two months. Every day we would dance from morning to night, and I would think up ideas for a crazy number of workshops that would keep us moving our bodies until we were completely worn out. As we danced, one of the things we would do was to imitate the physical habits and idiosyncrasies of the other dancers, and it was doing that which made me think of “emotions” as a subject.

During the course of human evolution, we surely didn’t always have clear feelings that are like the things we call emotions now. But as our brains evolved, we obtained emotions that can be distinguished from other feelings. When we dance, the contents are different every time, and it is not as if we are expressing individual feelings. Still, it is something certainly that involves feelings, and there are people who will cry or laugh together at the same moments in response to those “emotions” they perceive.

And with music, the feelings/emotions we get from a piece of music will change according to the circumstances under which we encounter them. When a certain memory comes to mind, there will be people who respond to it quickly with concern and others who will just brush it off with no concern. We will often create the seeds of emotions within ourselves, but they remain asleep inside us unless there is some outside stimulus to awaken them. But it is very difficult to awaken or to stir them by ourselves, and I feel that is something that applies to dance as well. That is the line of thought that led me to choose Emotions for the name of the series. I did a lot of performances of pieces in this series in Europe and other overseas locations. In New York, it was La MaMa (the experimental theater opened in 1961) where they let us perform one, and it was the founder of La MaMa, Ellen Stewart, who asked me to perform there.

The Encounter with Tatsumi Hijikata

- Later, Hijikata finally did resume his dance activities at plan-B, didn’t he?

- At first, he did symposiums and slide-only screenings. He would give slide projectors to four or five people, and then Hijikata-san would compose the action and have them project the slides on the walls. He did all of the directing, and he conducted the music from inside a booth. It was something incredibly new. The slides were composed by Hoshu Kurokawa, a film/video artist who had also been at our Body Weather Laboratory. He liked Hijikata-san and took a lot of pictures and made images from the 1960s using only photos. They are things that it would be good for young people today to watch repeatedly.

After that we had young Butoh dancers performing solos every day, and that is also when Yoko Ashikawa (a core dancer at Asbestos Studio, at which Hijikata was based) began dancing. And each time, after those individual dances were finished, Hijikata-san and I would go out on the street and discuss what we had thought of them. That became a great private lesson for me. He would say that all of them were doing Butoh that was rooted in their individual characters. Intensively persistent people would dance with that intensity, and ones who loved to jump would do almost nothing but jumping. Those were the kinds of things he pointed out.

He would also talk a lot about people’s physical habits, or idiosyncrasies. He would say that the position I was holding my hand in at the time was probably one of my habits, because it was easy for me to create a space that way. He would say that it was important to maintain that as a position but added that there was also something that should be next to it.

And that would indeed be true, because when he danced, Hijikata-san was always shifting his body. If you thought he was standing at a particular spot, in an instant you would find that he had shifted to another spot. The moment you find yourself next to someone, all of a sudden everything in that space changes, he would say. For everyone, they themselves are important, and no one thinks of their habits as habits, so they will dance in the positions and the directions that they like. And thinking about how to break out of those tendencies/patterns is what he called the “Butoh-Fu (Butoh notation)” approach.

What is being called “Butoh-Fu” today is something a code, and people think if they abide by it, they can dance Butoh. But the Butoh-Fu that Hijikata-san was talking about is different. To him, what Butoh-Fu meant was a method for learning from nature and discovering your body. So, it is not one thing that a person could write down [like a method]. It is something that the bodies of all the dancers participate in, and the contents are the same, but the writing down [of notes] is the personal responsibility of each individual participant. Everyone was told that they should write things down and learn by themselves. Each person would listen to what was said and wrote down the essence in handwritten notes.

In Hijikata-san’s later years, in the last of his lectures, there was so much to write down. For example, he might say that today we will focus on the haiku of Koi Nagata, and then he would have everyone write down the poems. He placed great importance on the writing of notes and [sketching] of images. At times, he had us doing things like spending a day in a chicken coop and then the next day he would ask us to all do a chicken dance.

This was certainly because Hijikata-san didn’t take the Western word “choreography” seriously. The word “choreography” that came from the West was translated into Japanese as the word furitsuke, but of necessity, a variety of different nuances were included in that English-in-translation [previously non-existent] Japanese word. But he argued that Japanese dancers had not applied their intelligence sufficiently to recognizing those nuances.

Hijikata-san was thinking of something completely different from Western choreography, and the aesthetic he embraced was one of evoking a “revolution of the body.” I learned that directly from him and I wanted him to reshape my body, as if working with like clay. So, my feeling was almost that I would give him my body and I accepted [Hijikata’s] instruction with a determination not to move purely of my own initiative. - That is what eventually led to your performance Ren-ai Butoh-ha (Love-Dance School) in 1984, is it?

- That’s right. When I first saw Hijikata-san it was in the 1960s, so it took about 15 years after that first encounter. This was the only time when I worked closely with Hijikata-san. I wanted to be taught in the same way that his other apprentices were being taught. When I first saw him [perform], I thought he was amazing, but the impact was so strong that I thought if I stayed too close to a person like him his influence on me would be overwhelming, so I kept my distance at the time. If likened to a family situation, my feeling was like that of a [prodigal] son who had left home with a determination to be independent.

When I finally asked him if he would choreograph for me, he said, “You look sharp, so I’ll do it.” I believe that his meaning was not that I was intelligent but that the timing of my request was good. - How was this title decided on?

- Hijikata-san named it Butoh-ha (Butoh-school), and I was told that the addition of the “-ha” school/style) meant that I should accept the piece as a deliberate “teaching,” in a relationship where I was being taught. When I made the catalog for the performance, I added the characters Ren-ai (meaning love) to the Butoh-ha, so the name of the piece meant Love – Dance School. At that point in time, I had already danced 1824 hours of Hyper dance on the 1970s, and that probably meant I had dance about 2,000 times, and after each dance I wrote down memos about it. On this occasion of his choreographing for me, I gave all of those memos to Hijikata-san to look at.

- What kinds of memos were they?

- They included a variety of things. Practical things like the names of the people I met, things like problems with my body, and sometimes some rather philosophical musings…. When I showed them to him, Hijikata-san said, “Let’s put all the memos together into a catalogue.

After sending it all off to the printer with little time to spare, we went to a coffee shop together, and it was there that Hijikata-san said, “Is it love?” I admit that I was embarrassed when I heard that, but then he said, “Ren-ai Butoh-ha (Love – Dance School)” is OK, because we will create the piece together. In other words, it meant a school of Butoh with just the two of us.

“Butoh-Fu” as a method for discovering the body

Yo! Don Quixote

(Dec. 4 – 6, 2020 at Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre – Playhouse)

Photo: Itaru Hirama

- This was the first time after leaving modern dance that you danced a piece choreographed by someone else, wasn’t it?

- It was so fascinating to do. I think it’s close to the origins of what came to be called “Butoh-Fu,” in the way that it involved imprinting on your body things learned through stimuli from nature, or the practice of searching out existing types of movement. For example, struggling to capture the essence of the words “the wind gently touches the surface of the flower” in movement and then gradually working to expand things from there. Or, grasping things felt within the body or in the heart and then projecting them outward and gradually building on them.

- What form did his instruction concerning the choreography take?

- It was all done through words. He kept mumbling things in way of instruction, but never once did he use body to show me actual movements.

- Both of Tatsumi Hijikata’s books, Yameru Maihime (The Sick Dancer / also translated as The Ailing Dancer) and Bibo no Aozora (Handsome Blue Sky), are written in a style that strings together very aesthetic or poetic lines. Are those the types of words he used [to guide you with the choreography]?

- They may have been close to that, but it was more …, more specific. Things like, “The wind ruffles your hair and pulls it back and back and back. It stretches on for tens of thousands of kilometers.” Or, “Beneath a grapevine trellis, with your back hunched, you reach out to your homeland 3,000 kilometers away.”

- Although your own dance is connected in some way to Hijikata’s dance, I feel also that it is completely different.

- It is completely different. Even if I tried to dance like him, I think my body might defy the attempt, and I didn’t have the desire to dance like him [to begin with]. Hijikata does almost nothing in his dances. The performance by Ningenza of the work, Honegami-touge Hotoke-kazura by novelist Akiyuki Nosaka held at Art Theater Shinjuku Culture in 1970 was the epitome of that style. Performing as the main dancers in it were Hijikata and Michiko Soga.

Hijikata was inside a huge cauldron, and when the performance began, a group of young men carried that cauldron out from behind the audience seating and slowly carried it up on stage and put it down with a thump. Finally, he climbed out, began to scoop the rice that was stuck to the walls of the cauldron with a rice ladle and ate it, and then he just stood up. Everything up to that point had taken 30 minutes. And during that time, he didn’t do a single thing that could be called dance. All he did was just get out of the cauldron, lay down, looked inside the cauldron, put rice in his mouth and eat it, and finally he just stood up. I was really surprised by it.

He thought, “I am an example, just one example and by no means someone who should stand out above [others].” - Was it the premise that everyone’s body is different so everyone should dance differently that led to this style where he did almost nothing that could be called dance?

- Yes, it was. I believe it was Hijikata’s dream to have each individual be themselves? And for that reason, I think he probably believed that eventually, “Butoh” itself would be an obstacle. Because before he passed away, he only spoke of odori (dance). For example, partly because of the age difference, like a Hijikata-style nickname, he called Kazuo Ohno (Butoh dancer) sensei (master/teacher) (Hijikata had a habit of making up unique nicknames that he called people by), but I think he most certainly despised the way he (Ohno) went on to become a sort of guru or god-like figure.

I also disliked Kazuo Ohno in his later years. Japan is full of people who reach his age and can no longer move and thus become confined to wheelchairs. So why did people to call what he did dance even though he wasn’t dancing? I want to ask that question of all people who dance. I’d ask them if they see dance where there is no dance to be seen. They only see it with their emotions. They are not participating in the history of dance. They are just being made to participate in the festivities of the old elder named Kazuo Ohno. I would like to say that, when he was dancing, I thought of him as a genius in dancing.

I think I feel this way partly because I was no longer interested in Butoh after Hijikata’s death. When dance traditions, especially like ballet that had taken a tremendous amount of time to develop were introduced to Japan, the Japanese accepted it with unexpected ease and became thoroughly absorbed in that kind of European beauty. If I had been born in that period, I believe that I, too, would have sulked over it to quite a degree. To tell the truth, I think that Hijikata-san also wanted to tear apart that kind of devotion [by the Japanese] to foreign culture. He had to teach in a way that even people who would otherwise have turned to ballet would end up dancing like Butoh dancers. - The two of you also talked often about originality, didn’t you?

- Yes, in the sense that there is no such thing as dance that can be called “my dance.” We talked about the fact that dance is not something that one can own and put your own name on it. And if there is something that you can possess in that sense, where are the seeds of Butoh? For example, a ballerina may talk about “my dance,” but the important question is from what point did that begin. That “my” means nothing more than the fact that the ballerina is dancing ballet. It may sound like over-rationalization, but it is actually true, because nothing will be born in a space where the dancer says, “I am going to show you my dance.”

- Hijikata died less than a year and a half after the performance Ren-ai Butoh-ha (Love – Dance School).

- When I moved to Hakushu, Yamanashi Prefecture in 1985, Hijikata-san was still alive, but he was already preparing for his death. He went regularly to Yamagata for appearances in the movie 1000-nen kizami no hidokei: Maginomura Monogatari (Magino Village: A Tale) (director: Shinsuke Ogawa). He was hospitalized in the fall and then died on January 27, 1986.

I think he knew he was going to die. He sent out messages to about a dozen people saying that he was going to die that day, and naturally I was astonished to hear that. And after talking with them all, he died 30 minutes later.

If asked, I would have to say that I truly admired his strength of will.

There is no such thing as “my dance”

- Around 1985, you moved to Hakushu, it was a very busy time for you with the establishment of plan-B, the performances of Ren-ai Butoh-ha (Love – Dance School), and touring in Eastern Europe on invitation from a Czech revolutionary group. Why did you decide to move, and why Hakushu?

- At a time before the completion of the Chuo Expressway, when I was still in my last year of high school, I used to ride a motorcycle along the Koshu-kaido highway from Hachioji, through Yamanashi Prefecture and all the way to Suwa (Nagano Pref.). At the time, groups of free-wheeling motorcyclists were called Kaminari Zoku (literally: “thunder tribe” motorcyclists), but I used to ride by myself without any other bikers. I always remembered the great views along that route of the Yatsugatake mountain range and the Southern Alps, and when I began to wonder if I couldn’t rent some land to cultivate and a house in that area, I actually found a place. And the fact that I had luckily found that place was the main reason I chose to move there.

- When did you start to think about moving to Hakushu?

- I formed Maijuku in 1981, the first studio was in Hachioji. There was an ill-tempered landowner there. But miraculously, after taking him out drinking and talking about things that he played at as a child, he took a liking to me and decided to build me a studio. It was a prefabricated structure, but it was large enough with 60 tsubo (about 198㎡), and under the floor he laid tires to absorb the leg-shock involved in dancing for us. I didn’t pay for the construction at all. I paid only the rent after it was completed. I rented it for four years, but I couldn’t pay the rent the last year. So, I left it and moved to a more convenient studio in the same city.

And after I could no longer use that studio, that is when I moved to Hakushu. But at first, I still kept the studio in Hachioji and rented it out to a theater company that wanted to use it. Later I felt bad about what I had done to the landowner in Hachioji and I apologized and returned the studio to him. And to pay something back for the couple of years of unpaid rent, I sent him some of the rice I grew in Hakushu from time to time. After a while the landowner passed away, but I still remember him as a wonderful person. - Why did you decide to start doing agriculture?

- There were many foreigners in our Maijuku school, and at the time, 30 or 40 young people were all working at part-time jobs. It was tough to come to dance practice after working during the daytime, and often their day jobs kept them from being able to do their training and practice, which was like putting the cart before the horse.

At the same time, I had qualms about practicing dance in a studio in the city. I couldn’t help having doubts about whether practicing—one, two, three, four—at a clean studio could lead to real dance. And when I actually started farming, I had to reluctantly admit that was no way to pursue dance. I couldn’t help but think about questions of life, of plants, perspective concerning the natural world, views on life and death, which came to me time and again. I got the feeling that these were all things that sprang from the earth, from the soil. I constantly had the feeling that I had to think about this question and that question. And I found that dance was one of those questions that emerged. - So, dance changed into one of those fundamental questions?

- That is what it had changed into. But it wasn’t that dance emerged as something unrelated to the rest, it was because I had been doing dance [for so long] that I realized its place as one of the questions. If I had only been thinking about life and death, it might never have given birth to dance [in me], it might have connected to something else, or to some more common way of [making a] living.

Hijikata-san was always saying that we have to give real flesh to words, we have to work words into our body [make them part of our flesh and blood]. I believed that with all my heart, and I still do. And that is why I found another place besides dance to work words into. - Did your farming go well from the beginning?

- Not at all. First of all, no one would lend me land to farm. I was able to rent a house, and once I did that, I would take the owner, his relatives and other people out drinking. Drinking and drinking, singing and singing. Since there were parts of the house that needed repair, we started repairing it here and there, and when that started, those people I drank with would all come to help out. That started the birth of a sort of community. And that in turn led me to begin studying about the region intensely.

- Was it a time when the number of fallow fields was increasing rapidly?

- Of course, it was. The local people’s sons and daughters were all going off to live in the cities, so there was a lot of fallow land and fields that were left untilled. It seemed that we should have been able to rent some of that land, but the locals didn’t trust young strangers like us who came saying they wanted to rent land. The winters are cold here, they would say, and they told us that once winter set in people like us would surely run off and leave the land. It also happened to be just after the incident of Aum Shinrikyo [the Japanese religious cult group responsible for the 1995 sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subways] and my group of young dancers were a ragged bunch that surely looked suspicious to them.

- The year you moved to Hakushu, you had your “1st Minakata Kumagusu Project.”

- One of the young men who had participated in the Body Weather Laboratory was the son of the priest of the largest temple in Kishu Tanabe, called Kozan-ji. He said that although he had left home, at his family’s temple there was the grave of the famous naturalist and the biologist, Minakata Kumagusu. So, I started studying about Kumagusu and became very interested in his work. I decided to do a “Kumagusu Project,” and when I danced on the beach at Tanabe as part of it, Kenji Nakagami (a novelist from Kishu) came to see it. That night we went out drinking together with him and got drunk with our group’s young people, and while talking and doing things like an arm wrestling tournament, we became friends.

After that, when we started the festival in Hakushu, Nakagami-san also participated, though at first, he got in arguments with the artists. You know, in the 80s, everyone would have arguments to get to understand each other better (laughs). Nakagami-san was always talking about things like Gilles Deleuze’s concept of “the body without organs.”

The mutual influence of dance and agriculture

- You started “Hakushu Summer Festival” in 1988. What led you to do that?

- One thing that led to its start was a visit I got from the artist Kazuo Kuramochi. He had created a great [sculpture] work that was installed in the Ochanomizu Square, Building A designed by the architect Arata Isozaki, but later he had suddenly been told to remove it. He said that when thinking about what to do with it, my place in Hakushu came to mind. Because he made his request to have it placed on my land with such passion, I decided to re-construct it in a small empty plot of land I had that had become the playground for our chickens.

When the work was reconstructed there, it was a structure that stood about ten meters tall. The next day it snowed, or did it rain first…? Anyway, within three or four days of bad weather the structure took on a completely different appearance from when it was first set up. I thought it was amazing, and since I had a lot of artist friends, I contacted them and invited them to come see it. Eventually, about ten artists, including Noriyuki Haraguchi, Noboru Takayama, Koji Enokura and others rented a microbus and drove to my place.

So, when they arrived, I gave them a tour around the village, pointing out each of the different sights to be seen and such. And then I said to them, “You take your works to a museum for an exhibition and then take them out again after it is over. Are you alright with that? Rather than that, how about setting up works here with the intent of exhibiting them ‘until they decay and return to dust’?” To that, everyone immediately said, “Let’s do it.”

The first thing we all agreed on was to create things on-site, rather than bringing in already finished works to install on our land. I told them it was OK to call in a lot of helpers because we could provide them with lodging while they were here. Another thing we specified was that, because it was farmland we would be creating works on, we all had to spend time getting to know and hanging out with the owners of the land. Also, we decided that whoever participated would contribute a set amount of 80,000 yen to help finance it as a festival. Everyone agreed to these rules and we stuck to them till the end. - How did you get that money?

- From the start, we created a promotional operating committee. The members included the President the Pia publishing company, Hiroshi Yanai, and was Arata Isozaki also on it? There was also Atsushi Shimokobe, who was called the “god of bureaucrats.” He was responsible for Japan’s national land reorganization planning after World War II, but anyway, a hard person to explain in a word, and I’m sure it was Kobata (producer) who brought him. And he saw me dance one day. About three days after that, we met when he said he wanted to talk with me over tea. He told me that because he couldn’t concentrate on work the day after he saw me dance, would I please dance for him sometime on a day before a holiday (laughs). We became friends after that, and when he would invite me to go to a symposium or something we would sit in the lobby and talk about unrelated things like trees (laughs). Those talks would include things like the fact that there seem to be many people who have heard trees talking to each other.

Through the connection with Shimokobe-san, the president of Suntory, Keizo Saji-san, also supported us, since there was a Suntory factory in Hakushu. But, I don’t even remember ever thanking him directly because Kobata-san had handled all of the negotiations there. Whenever we seemed to be running out of money for the festival, we would organize a meeting for people to talk with Atsushi Shimokobe, and the people who attended would leave a donation behind when the left. - How did you decide on the themes for the festivals?

- I decided them on my own. I would write them as one line to put on the side of the festival posters. They were the words of people like Kiyoshi Miki (the philosopher) or Norio Nagayama, (the death row inmate, novelist). Sometimes they were phrases I made up. More than 20 times, I decided them all and showed them to Kobata and everyone. Those single lines determined the overall theme each time.

- In the Japanese contemporary art world, the “Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale” planned by Fram Kitagawa is said to be the first of the international art exhibitions held not in museums but in large areas like an entire rural village. The first of those was in 22000, but your festival in Hakushu began more than 10 years before that. The sculptor Richard Serra was among the participants who came.

- Richard Serra came for the second or third holding. When I asked him to, he decided to participate. Before that, he had an exhibition of small lumps of iron at a gallery in Tokyo, and I danced naked at that exhibition.

For Hakushu, he created a video work that showed the process of him leafing through sheets of paper in a gradation from white to black, which he filmed from above. I also used that video when Serra participated as stage art designer for the The Rite of Spring (in 1990 at Théâtre national de l’Opéra-Comique, Paris) that I participated in. - In 1993, you changed the festival’s name to Art Camp Hakushu. Why was that?

- Young people who had continued to come to the festival as volunteers for years, started to feel that they wanted to get closer to the creations. So, we made the big decision to increase what until then had been a five-day festival and extend it to a full month so that we could hold a variety of workshops. At the same time, we decided to call it a camp in order to make that concept clearer.

And then I started the camp for children. The parents only had to bring them, and no other provisions were necessary at all. The children ranging from the first year of elementary school to the third year of junior high school all lived together in the camp. All of them stayed in tents. There was a parade on the first day of the festival where they paraded with animals. There were chickens, cats, dogs, goats and also donkeys. It was their daily routine to take care of the chickens and dogs and clean out donkey droppings. And they also make their own T-shirts, hand-drawing them with paint.

Since I had said that the children didn’t have to do their school homework while they were at camp, so some worried parents came to pick them up early. But when they did, they were surprised to see even the elementary school 1st graders washing the dishes after meals. I told them they were surprised because they never made their children do it, and I suggested that they should try having them do it. I still correspond with some of the children who came to our camps. - Was the art camp also supported by members of your Maijuku?

- We disbanded our Maijuku in Paris after performing at The Rite of Spring. Because when it began to look as if the members were starting to think as if it would go on forever, it became more boring than ever. So, we said, “Let’s quit.” The feeling of stability wasn’t bad, but if things feel so stable that you start to sit in a posture with your butt flat on the ground, that’s certainly not good. From the beginning, I thought it was good when you can just barely stand, and that is the feeling I like. But even then, there were people who kept coming.

I would give the groups names when the time called for one, but overall, the name doesn’t really matter. When you give a group a name, it can’t help but give them the appearance of a type of proper group, but no matter what the relationship, there were never any boundaries between them for me. I longed for things like “colleagues” or “gatherings” [of people] to work with, but it wasn’t as if there was something special, some rank, connected with the people who had been around for a long time, and it was OK if some wanted to step away for a while.

At the time, there were many young people who were coming and going around me, and they weren’t only dancers either. There were also people involved in things like film, art, literature and science. And the Body Weather Farm name was one that derived from our Body Weather Laboratory in Tokyo. And they were just words that I had found by chance, and it was just words in the sense of “body weather.” So, they were all just “expressions” that developed from things like that. And because of that I just want to say that the origins were the people that I happened to meet at those times and in those places. - After that you formed the Tokason Buyodan (Tokason dance company) in 2000. You took the name of a fictional village depicted as an idea of the poet Issui Yoshida. How was this group different from Maijuku?

- There were many young people from foreign countries at Maijuku, the number of Japanese members increased at Tokason Buyodan. That made it possible to put more value on the Japanese language, and that narrowed down the things we focus on making into dance. For the debut production our Tokason Buyodan performed, I mostly choose a few prints from Goya’s “Los Caprichos” to create dances from. In that process, you would find places in them for your body to take part, and then work to find where your body actually is at the time.

- Why was it Goya and not something like the Japanese “Hokusai Manga” prints?

- I thought it [using Hokusai prints] would tend to tilt the movement, and although I could turn those poses into dance, I think it would be close to impossible for the others. Hokusai is amazing for his ability to capture moments as precisely as he does in the Hokusai Manga print series. Because they contain almost no hints of lies.

That said, I was also smarter by that time than I had be at Maijuku (laughs), and my body had more experience by then, so the way I taught, the way I used words was probably several times better. However, because the people who were listening to them were all different [in their interpretation], so it is hard to say anything for certain. In terms solely of the number of performances, I think the number done by Tokason Buyodan was far more. - How did you interact with the members of Maijuku or Tokason Buyodan?

- The ideal was for each of them to find something on their own and begin working on it by themselves. But in the process leading up to that point, they had to work by themselves on building a body that really wants to dance, and that is what I helped them to do. I also think I was preparing the proper environment for that.. But one thing that was always true was that I didn’t teach them how to dance. And although this is another story, I didn’t teach Butoh either (laughs). For example, that is one of the things I would say at the beginning of each two-month workshop. And at the end I reminded them again, but when they went back to their countries, they used the term “Butoh school.” Almost everyone is like that. It always disappointed me to hear that. They continued to [wrongly] call me as a “master of Butoh.” No matter what I said.

Holding an Art Festival

- You traveled around the islands of Indonesian in 2004. Is this when the concept of Ba-Odori (literally: place dance, also translated as Locus Focus) began?

- That’s right. The Asian Cultural Council (ACC) contacted me and asked me if it wasn’t about time for me to travel around Asia. When I was told that they wanted me to meet with artists in Asia and have various kinds of exchanges with them, I refused at first. I didn’t know what benefits there would be in talking with them. I’m not the kind of person who does things like that, and I wasn’t particularly anxious to make any new friends. In the Indonesian dance world, I had already known for a long time Sardono W. Kusumo (dancer) who became president of the Jakarta Institute for the Arts, and if I went there, I knew I could meet with him. So, I didn’t think I had to go out of my way just to meet artists there. When I told them that I wanted to visit villages and visit islands and that I wanted to see festivals and dances there, they arranged for me to go to seven or eight islands and I was able to see a lot of local dances there.

When I went to Indonesia, I felt that almost everyone in the villages and on the islands seemed to be an artist. I was asked, “When you dance in Japan, do you get paid for it?” They said, “On our island, everyone dances and sings and plays music.” One day when I was departing from a small village after a stay there, it was decided that we would all dance together. When I suggested that we all dance freely, they asked, “What does it mean to dance freely?” They said, “We have dances that we have danced since olden times. That is what we all dance.”

That is freedom. For them, dancing the dances they always dance is “dancing freely.” I had never expected that! [Shimatta!] It came to me as a revelation. What a real and powerful experience that was for me, and I felt that I had been taught something wonderful and more enlightening than any lesson I might have learned while talking with artists in a salon type discussion event.

After I came back to Japan, I received the Asahi Performing Arts Award in 2006, and at the awards ceremony I said, “With this I will stop performing on stage.” I said farewell to the theater stage, and from that point on I started doing my “Locus Focus.” Making the common places that we normally take for granted my stage turned out to be the method that suited me best. My intent was to try to keep doing it as long as I could, to deepen my understanding—because I thought this to be the best way to further cultivate and develop dance within me.

And having people see one’s dance leads to further nurturing and development in one’s dance from there. In some people’s cases it may be called music, and that included, I think it can all be called dance. So, there is no need for all of them to become a dancers. - About Locus Focus, you have said things such as that it is a process of peeling off the skin of a place, haven’t you?

- You could describe it as a sensation of peeling off a single layer of skin from the surface of the place. And you could say that the moment the dance begins, the people who live there and are used to the place will suddenly see it in a different light. The feeling can be something like a sense that the place is alive and breathing in a different life [they hadn’t seen it in before].

- Does that mean you serve as a catalyst [causing this change]?

- That’s right. For instance, I have an Indonesian friend who was doing pearl culturing in the Kangean Islands. He said that when I stood up on a boat floating on the water in the sea there, even without looking at my body, the landscape began to look different. He said that the sea had a totally different appearance from usual.

Another case is a very large black desert in Iceland that I went to with the late photographer Keiich Tahara. No matter how much you stretch your body, you can never reach the edge. It is virtually like the golden edge of the universe, but there is a sense of place even in such [an amazing] place. I felt that it had a sense of place that was nearly infinite. [But the task is still] to peel off the skin of such a place. - When you spoke of Indonesia, I recalled that there is a dance in Bali called Sanghyang Dedari in which the [young girl] dancer goes into a trance, isn’t there? Watching you dance, sometimes it appears that you are in a similar state. You have said there is no way you can do a trance, but is there some technique of control that you use when you dance?

- For example, there are moments when I concentrate on the soles of my feet and depend on that to stand or to move, and there are other moments when I am off-balance, or I am not fully in balance. I may deliberately put myself off balance, and there are times when I do that consciously and times when it just happens. But with me, more often it is the “just happens” case.

For this reason, there are cases when things that aren’t going well can soon evolve into something interesting. Very seldom are things fully under control, but they are being shifted intuitively between a state of control and the haphazard. This “haphazard” can also perhaps be called “makeshift.” But I think that can probably be a very important component. - In order that do intuitive shifting when it is necessary, you have to be constantly training your body, don’t you?

- By training my body, and also the material of dance within me—what Hijikata called the “inner material”—you bring speed to them. In my case I use the term “cellular material,” a rather affected term, but I guess it would be most correct to describe it as something in the mind that is faster than the movement of the body.

That is why you can do many things that wouldn’t otherwise be possible, in a word you could call it “perfunctory” (but also “timed as necessary”). Something inside of you, some sense, is brought to bear in a surge. I am not living to enlarge that capacity. Just a moment is enough. It draws away farther and faster from human banality. Because I am dealing with cells, on the cellular level. - The philosopher Roger Caillois, who described your dance as Unnameable Dance, wrote a story about a shaman in his major work, Man, Play and Games. He wrote that the shaman’s trance is all about acting, but it is authentic at the same time. And [he says] that there is always an accompanying assistant to prevent accidents. Do you have both a shaman and the assistant within you?

- Well, basically the shaman knows with tremendous speed when we need to be ready for the next thing that is coming at us. In short, the shaman knows when something threatening is coming When I dance and my condition is good, I feel that way as well. For example, when I am dancing, I often may get a feeling [premonition] in cases like when the clouds are moving quickly and that sends sunlight directly at me. In some cases, I may feel that I don’t want the sunlight to hit me, so before it does, I will face the other way, but at other times, I may invite it to hit me straight on (laughs).

- That must be a technique that you’ll never learn if you don’t have the talent to sense things like that, isn’t it? By the way, there is probably most often no music when you are doing Locus Focus, but are you hearing something like [music] in your head?

- There is nothing like music playing in my head. But, strangely enough, there are times when I feel something like a song being sung inside me. But that same sensation happens when there is other music playing, and also when there is only silence around me.

For the viewer, the best moment may be when the sound and the dance come together in unison. But the ideal situation [in Locus Focus] may be when the ambient sound of the place and the dance do not seem to restrain or harmonize with each other at all, and yet there is still a sense that they appear to be, or sound as if, they are interacting with each other. - In your place dance performances, you often appear to take what could be called a “fetal position.” About this, you have said that even though at times it may appear to be an easy cliché, I still do it regardless of that perception. Could you please tell me the meaning of that “regardless of….”

- For instance, even though there may be a hundred different fetal positions, what each viewer chooses to see in their mind is only one fetal position, isn’t it? That means that it is the individual viewer’s interpretation of what they are seeing in front of them at that moment. And I think that is enough as it is.

Of course, what I do is different every time. The place is different, the timing is also different, the conditions are different, my body weight/thickness is also different, as is the flexibility of my body. Since it is human beings that are doing it, you will find that each time the result is different, if you strictly measure it. So, the music you hear there is also different. Each viewer’s perception will be different. People who say that the costume is always the same are ones who have lost the child’s heart they once had. What’s wrong with playing the same games over and over? That is what it means. For me, it is all happening in the here and now.

As we know, Shigeo Miki (anatomist, embryologist) said that from the time of fertilization in the womb until our birth as a child, we re-live billions of years of the history of the evolution of life. What I am talking about is close to that. It may possibly be that, by dancing, I amshowing people the process of being born again and again. Or, maybe I have been showing the birth of places each time. - You have danced more about 3,000 times until now, haven’t you? It may be that you are being reborn in those places each of the roughly 3,000 times.

- That may be true. So, rather than a feeling that I danced well, I like the sort of feeling that I have shed my skin again. But, because I am dancing too much, I may write it in my profile like that, but to be honest, however, it is surely far more than 3,000 times. So, the fact is it doesn’t really matter (laughs).

- I’ve heard that you will be doing theater performances with the theme of Ryokan (an Edo Period [1603 – 1868] Soto Zen sect monk, poet and calligrapher) teamed with Matsuoka-san at Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre in December this year. I’m really looking forward to it because I feel that there is some ideological overlap between you and Ryokan.

Thank you so much for your time for this long interview. - (Interview was held in Kyoto on February 26 and March 1, 2022)

+ References, Movies, Websites

Min Tanaka, Photos by Masato Okada, UmiYama no Aida (Between Mountain and Sea) (Kousakusha)

Min Tanaka, Photos by Masato Okada, Boku ha zutto hadaka datta (I was naked the whole time- the Body Theory of the Avant-Garde Dancer) (Kousakusha)

Min Tanaka + Seigo Matsuoka, Ishindenshin-Kotoba to karada no Osaho (Ishindenshin- words and body etiquette) (Shunjusha Publishing Company)

Written by Ben Watson, Translated by Kazue Kobata, Derek Bailey- and the Story of Free improvisation (Kousakusha)

Tatsumi Hijikata, Yameru Maihime (The sick dancer) (Hakusuisha)

Tatsumi Hijikata, Bibo no Aozora (Handsome Blue Sky) (Chikuma Shobo)

Issui Yoshida, Zuiso Tokason (Caprice Toka Village) (Yayoishobo)

Hanjuro Shiono, Tama wo horu-Hana to Jomon wo otte (Digging Tama- following Flowers and Jomon) (Musashishobo)

Written by Roger Caillois, Translated by Ikutaro Shimizu and Kazuo Kiriu, (Asobi to Ningen (Man, Play and Games) (Iwanami Shoten)

“Eureka,” February 2022 issue “Special Feature--MinTanaka” (Seidosha)

Human documentation “Min Tanaka Dancing on the Soil” (NHK Broadcasting)

Directed by Shunya Ito, Hajimari mo Owari mo nai (There is No Beginning and No End)

Directed by Isshin Inudo, Nadukeyo no nai Odori (The Unnameable Dance)

Min Tanaka Official Website

http://www.min-tanaka.com/

Peeling off the skin of a place with Ba-odori

Related Tags