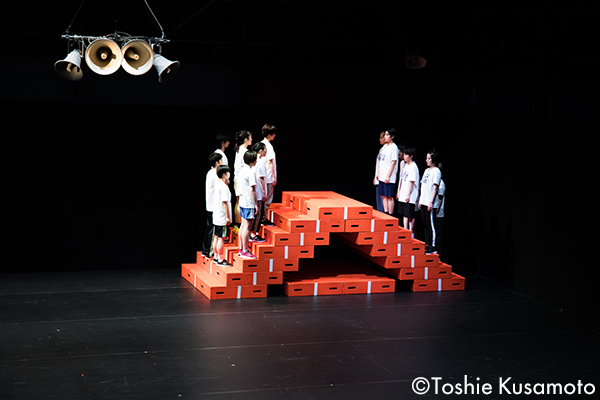

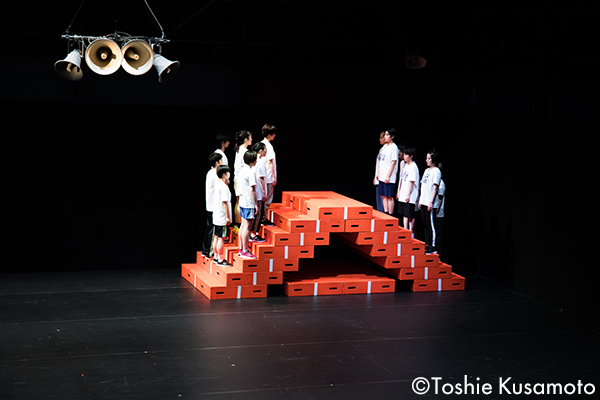

Kedagoro Sewol

(May. 26–29, 2022 at KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre – Large studio)

Photo: Toshie Kusamoto

Kedagoro Dance to confront real cases

The Passion of Reisa Shimojima

Photo: Mizuki Sato

Reisa Shimojima (born 1992) is a choreographer and dancer who leads the dance company Kedagoro, known for presenting works based on things like actual incidents of the past. Among Shimojima’s works are Sky (premiered 2018, dealing with the madness and conformity pressures within extremist groups such as the Aum Shinrikyo cult and the United Red Army (Rengo Sekigun) which eventually led to numerous murders), Because Kazcause (premiered 2021, based on the case of Kazuko Fukuda, who was wanted for murder and evaded being arrested until just before the statute of limitations deadline), and others, as well as her latest work, Sewol (premiered 2022), in which she deals with the disastrous sinking of MV Sewol that caused many casualties. The Kedagoro productions, with their impressive and often rigorous motion performed by members, many of whom have never studied dance, and wearing things like disposable diapers as costumes, are now attracting attention from overseas as well.

Kedagoro Sewol

(May. 26–29, 2022 at KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre – Large studio)

Photo: Toshie Kusamoto

Monkey in a Diaper

(Feb. 2017, at Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse No.1)

Photo: Tsukada Yoichi

Kedagoro Sky

(Feb. 2018 at Yokohama Nigiwai-za Small Hall)

Photo: bozzo

Kedagoro Because Kazcause

(Jun. 2022 at Shimokitazawa Small Theatre B1)

Photo: bozzo

Related Tags