- How old were when you started playing musical instruments?

- From about the third grade of elementary school, I started learning classical guitar from older boy in our neighborhood. I was always uncomfortable about appearing in front of people, and I would suddenly get very embarrassed when I knew people were looking at me. Looking back, I think that I took to playing instruments because then I didn’t have to talk.

When I became a middle schooler, I got my parents to buy me a cheap electric guitar, and I really got into rock music. I didn’t feel comfortable in school, but there were a good number of neat adults who liked music, and they introduced me to the music of the Doors, the Rolling Stones, Sex Pistols, Janis Joplin and others, so I listened to a lot records by the mainstream rock, punk and rhythm and blues artists. We formed a band with a number of my childhood friends and older kids in the neighborhood and we played punk music at the local community center, but we were eventually barred from entering the center because of tremendous “noise” we made (laughs). My first “live performance” was probably when I was in the first year of middle school. - Did performing in a band give you confidence?

- My discomfort in appearing in front of people didn’t change. But the fact that it was punk and I could hide, in a way, behind the punk outfits perhaps made it possible to perform in front of people. I wanted to express something that couldn’t be put in words, and I think music gave me that means. Gradually, I got chances to get away from being a member of our local band and perform with adults as well. They were all older than me, and as a lead vocal I was a young girl of 14 or 15. I liked the Sex Pistols lead vocal Johnny Rotten (John Lydon), so I imitated him by jumping around as I sang.

- According to your website you first encountered the biwa when you were 17.

- It was just around the time I had turned 17. I was reading the magazine Ryukou Tsushin that my father bought every month, and in a feature article about Asian interiors I saw an instrument, an oud, on display. I mistook it for a biwa lute. It looked so handsome. It had a unique form, and I guess it also stood out because not many people play it. It made me want to try playing it. I look for biwa dealers in the telephone book, and I found that there was only one in all of Tokyo, the Ishida Biwa-ten (Ishida Biwa Shop) that still exists today in the Toranomon district. I call the shop and asked them to introduce me to a teacher who taught biwa.

I don’t know why, but they introduced me to the most famous master biwa player of all, Kinshi Tsuruta-san. Not really knowing anything at all about Master Tsuruta, I went to the condominium at the address I had been given to meet her. The master’s other students were sitting in the formal seiza style in a row along the corridor waiting for their lessons, and as I was led to meet the master, I just unceremoniously walked past them barefoot. Later I heard that my entrance had caused a big stir, with people saying, “That was a strange one that just came in.” When I met the master I saw her wearing a three-piece suit with her hair brushed straight back and wearing sunglasses, all in all looking very smart in appearance and exuding an strong aura. When she asked me what interested me about the biwa, I replied that I liked the shape, it really looked cool. And when she asked if I had ever heard its sound, I replied honestly that I hadn’t, and brought an outburst of laughter from everyone. Had it been any other school of traditional music I probably would have been shown the door immediately, but Master Tsuruta was really a progressive, avant-garde sort of artist. - I have also met her in the past, and I think she was probably pleased to have such a fresh young student come to her that way.

- I seems that she had liked to tell her other students often what a rare person (as me) had suddenly come to her in that way.

Since it wouldn’t be good to have someone who had never even heard the biwa before suddenly coming for lessons, I was given a cassette tape of the master’s performances to listen to. She was kind enough to tell me that if I listened to her tape and thought the sound was cool [as the shape] too, I could come see her again. I listened to the tape as soon as I got home, and I was so shocked by the new sound I was hearing, that it literally turned my whole world upside-down. From the uniqueness of the biwa’s sound to the vocals that I thought could not possibly come from the human voice, it all sounded so new to me even though I knew it was very old traditional music. It sounded so cool that even the Sex Pistols were no comparison. I told my mother that I wanted to become apprenticed to Master Tsuruta right away, and of course she was immediately against the idea (laughs). My father was also against the idea, but since I one who if I say I’m going to do something, I do it, so I went back to Master Tsuruta and asked her if she would teach me. That was just before I turned 17.

So I became an apprentice before I even knew right from left about the biwa or the music. And even though I knew none of the etiquette of the school, for some reason the master liked me and treated me with care and affection. I was able to study under the master for five years before she passed away. Of course I had already quit my rock band at that time. Although I was young, I had the feeling that the biwa was not something I could do in a halfhearted way, I had to be serious about it. I felt that I had to devote myself solely to the biwa, and I did it to the degree that I was in training eight hours a day. Nothing made me happier than being praised by master Tsuruta, and I did my best every time to achieve the objectives she gave me by my next lesson.

But sometimes when I met the master the next time, the things she said would change. “What? What does that mean?” I would think. When I would give her the answer I had come to after hours of practice, that would turn out to be no longer the right answer. But I always listened with open ears to what she said. Since I was devoted to the master’s kindness and magnanimity, I obediently practiced what she told me to. Today I know that there are many correct answers in the world of biwa performance, so I feel that my strange experiences at that time have been very helpful for me. - I have heard the Tsuruta-san would change the music depending on the capabilities of her different apprentices.

- That is correct. I think because I was a beginner, she would teach a simpler version of a peace, and then in time it would for the biwa, become more difficult. Since I had been studying guitar she understandably told me that I had good hands, but I didn’t learn the vocals for the first two years. I had been so shocked by her vocals when I first heard them that I knew I could never deliver that kind of vocal with my voice, so I had asked her to only teach me the biwa performance part. Biwa is basically an instrument for a repertory of pieces with vocals, but there are some pieces that are only and those are the pieces that I studied playing initially.

But after two years I had been through all of those biwa solo pieces, so master Tsuruta asked me if I wasn’t ready to begin learning singing as well. I still really didn’t want to do that, so I quit taking lessons for a while. When I did that, master Tsuruta continued to call my home almost every day, and she even asked my mother how I could be tempted to come back (laughs). My mother then said to me that she felt sorry for the master, so why don’t you go back to her. So I did, and I reluctantly began studying an old lesson song titled “Kongou-seki.” And master Tsuruta was very good at giving students praise, and she would say to me “Great!” and, “Your voice is really well suited to biwa singing. So, I was encouraged to keep practicing.

A year after I started studying the biwa I had my first stage performance with the biwa, and it went very well. The senior apprentices began to notice me and the master praised me for it. But my second performance was a failure. The lighting had been too strong and it caused my strings to loosen part way through the performance. When you are singing along with the biwa you can adjust the tuning as you sing, but since I was only playing the biwa then, there was nothing I could do. So I stopped in the middle of the performance to re-tune my biwa before going on to finish the piece. But I was so frustrated with the result that I ran off to the restroom and cried for about an hour. My mother and my seniors were all upset by my state, but master Tsuruta wheeled her wheelchair back to the restroom and praised me to my crying face, saying that I had been very brave. Usually, when something like that happened in a performance, most people would panic and not have the presence to stop, retune their instrument and go on to finish the performance as I had. She told me that what I had done had been wonderful, and that was such a help for me. She told me I had cried because I had been so frustrated, and that was proof that I wanted to improve and do well. So it was nothing to be ashamed of. Those words from the master at that time still ring in my ears today, and I will never forget them the rest of my life.

What is success and what is failure? Playing a part of a piece wrong is not failure. It is losing your mental presence that is failure, was what I learned. That is still something I think about whenever I go on stage. No matter what kind of accident or happening might occur, it is not a failure if you can keep your focus as a performer. Accidents can happen wherever you perform. And when they do I always remember that day. If a string comes uncoiled or if your plectrum misses the strings, if you are able to keep your composure, the audience won’t notice it. Even the other senior apprentices might think, “Oh, she just changed the arrangement a bit. And once you can feel that anything is OK as long as you don’t lose your composure, you can stay much more relaxed and confident. - Was it from around that time when you decided you wanted to become a professional biwa performer?

- It was a decision that was hard for me to make. I couldn’t decide for some time. When master Tsuruta passed away, I still hadn’t made my decision. I had no thoughts about becoming a pro and I certainly didn’t have a desire to become famous. I had simply been driven by my desire to meet my master as often as possible and be praised by her. I had continued the biwa because I liked Kinshi Tsuruta. Even after she was hospitalized, when I went to visit her she would be in bed but still persistently moving her hand as if it held her plectrum, and she told me that she still had many things she wanted to do. She spoke with passion about how she wanted to form a band with me as the main member of about five young women who would play the biwa standing up.

Just before she died, there was a biwa concert that I was participating in but I was so up in the air that I did things like forget my tuner in the dressing room and I performed carelessly, and the senior apprentice who would be my next teacher, Kakujo Nakamura, realized it.

As I was thinking that I might finally quit the biwa, I got a call from Kakujo Nakamura-san telling me that he had picked up my tuner and said, “I have it so why don’t you come and get it.” When I went to his place to get it, he talked passionately about the biwa and asked me how could I have played a performance so carelessly, and he told me that it would be a waste if I was to quit the biwa now, which put the passion back in me. In the hierarchy of the biwa world where the art was handed down from master to apprentice, it was taboo for someone like me to contact someone who was my senior like Nakamura-san without permission, but secretly I began taking lessons from him as my new teacher. As master Tsuruta’s life became in danger, the senior apprentices began to talk about how to split up responsibility for the master’s apprentices. In order for it to be decided that Nakamura-san would teach me, he first had to get permission from master Tsuruta, so I went together with him to the hospital where she was. She said that she thought that would be the best arrangement, so I then officially became Nakamura-san’s apprentice.

Until then, Nakamura-san had always been kind to me, but once I became his apprentice he became very strict with me. For five years, master Tsuruta had always treated me with kindness and affection, and after she passed away I went through six years of very strict training [under Nakamura-san] where I had to be hard on myself. In fact the training was so strict that I felt if I could bear through it, I would be able to endure almost any challenge I would encounter in the world. All of the form. If I tried to sit down of a floor cushion as usual, I was told never to sit down before the master tells you that you can sit. In those lessons with my new master Nakamura, there was always an air of tension. At that time I had already decided to become a pro, so I was being taught to acquire all the skills and mentality that would require. I was never praised even once. I was told to keep notes about what I tried to do during my lessons each day and what I thought. From that experience I have four volumes of notes, and looking back through those notes now still brings tears to my eyes.

I had a lot of trouble because I couldn’t make my voice sound the way my teacher instructed me to do. In the Biwa-uta (biwa song) performance style, you are told to concentrate on lowering your center of gravity and project your voice upward from the hips. Master Tsuruta told me project my voice from the abdomen, but master Nakamura said that the voice can never be projected from the abdomen. He was a type who thought rationally and as a teacher he was the type who used illustrations to describe the correct physical stance to project the voice from. Compared to master Tsuruta, who was often described as a genius type artist, you might say that master Nakamura was an intellectual type, and I was instructed thoroughly in both of their methods. But being given an explanation of how something should be done and actually doing it as you ware told are two different things. There comes a point where you suddenly feel you have gotten the essence of something, but even after I became independent from master Nakamura, things often didn’t go as I wanted them to. There are big differences between times when things are going well and times when they aren’t. But once you feel that you have really gotten a strong grasp of something, without thinking about it you enter a state where you feel that some other entity is singing through you. At such a time, it is best if the body feels “tubular” and as you sit in the formal [straight-backed] seiza posture [sitting on your calves] you feel suddenly and firmly connected to the overworld, and the feeling is as if your body is empty and that some other entity is performing through you. But you only reach that state when you are performing. That kind of unfettered voice just doesn’t come out in everyday training. - Is that something like a special tension that comes when performing?

- I really don’t know what it is. I think that probably there must be some kind of special switch somewhere that kicks in when performing, but I myself don’t know where that switch is. During rehearsal when we do a preliminary sound check and tuning, the volume will be so different from the volume that comes out in the performance itself that the PA technician has a hard time working things out. But that difference is proof that the performance has gone well.

- What kind of lessons and training do you do in order to master the art of Biwa-uta vocal performance?

- With master Nakamura’s method, you have to sing a lot and play the biwa parts a lot before they become yours, so you spend about six months working on one Biwa-uta piece before you can really understand it. The musical score is in very abbreviated notation, so you have to listen to your teacher sing in order to learn it. To learn the melodic intonations and the pitch, you just have to learn it all by ear, by listening to recording over and over, etc. You can learn enough about the superficial elements to be able to perform a piece in about two months, but it won’t get you to the point where you can sing and play as if your body is a tube connecting the earth to the heavens. Even if you are told to concentrate your strength in the pelvic area when you sing, you do know where to do that specifically. Of course, I understand it now, but if I were to try to teach someone how to do it I would tell them to keep squeezing with their lower back muscles and don’t relax it. If it is for an hour [performance], hold that tension there the entire hour. I say to hold that tension in the lower back muscles as if you were applying strength with your abdominal muscles when doing sit-ups.

- Does the way you sit also effect the way you play?

- You sit in the seiza position with your knees slightly apart. When you are using a chair, you get a sound that uses the lower back and hips as a cushion gets spring from that part of the body, but when you are sitting [on a cushion] on the floor in the seiza position, the cushion comes from your buttocks sitting on the flesh of your legs (calves). Because a woman’s kimono wraps tightly around the thighs, holding them together and thus making it difficult to sing properly, I wear trousers that allow me to spread the knees apart sufficiently or some other form of looser clothing. I train by using the spring of the lower back and hips to sink down, using its strength to drop the center of gravity solidly and then hold it there without releasing the tension there. In that way, if the lower body becomes solid like a rock, then the upper body is free to relax so that I can sing no tension in the face whatsoever. If you are conscious of the upper body your center of gravity naturally rises, which tightens the throat and makes the voice sound shriller. If, on the other hand, you concentrate tension in the lower back and hip area, the voice naturally comes out more fully.

I believe that as the voice rises, a number of things happen in the mouth that you are not unconscious of, so I sing without blowing the breath out. Probably, if there was a candle burning in front of me when I sing you would not see the flame quiver. In some of my original pieces I sometimes let out a whispering voice while blowing the breath outward, and I also use the sound of my breath on the microphone, but when I sing a Biwa-uta piece you will probably not be aware of my breathing to the point that you may wonder if I am breathing at all. With sounds like “ah –“ and “wa –“ where the mouth is opened widely, there is no need to use the breath strongly, so the sound comes out easily. But with sounds like “kee – “ and “ee – “, where you are more likely to apply force, the sound can easily become less pure. For words with sounds like that can tend to be forced, I take measures like breathing in slightly as I sing them so that kind of sound is not accentuated. - How about the technique of making the sound resonate inside the mouth?

- It is done without the feeling of opening the mouth very wide. You can naturally cause resonation in the mouth, but I think there is a good degree of difference in individuals regarding that. The kind of sound made by tightening the muscles of the pelvic area and [lower] back passes through the body and come out through each person’s mouth. Of course the size of each mouth is different and the things that happen there really differ by person, and from there you can change it to the kind of resonance that you like. You can’t make a voice without it coming out through the mouth, and in that process you can change the color of the voice in any way that you like. And it may be with the advanced technique of a skilled singer, but that is the final process that gives the vocal a finished, refined sound.

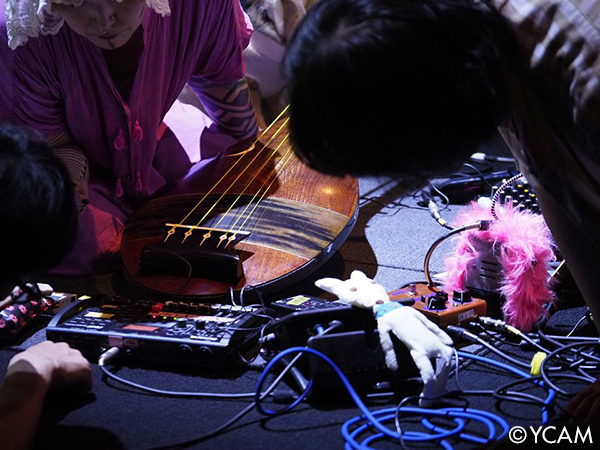

all of the strings of the biwa, they can produce a buzzy timber by the technique called sawari. The Tsuruta School Satsuma Biwa has five frets and five strings and sawari can be applied at any contact point along the strings. Depending on the performer, there are ones who like a powerful sound with lots of buzzing applied and ones who like a softer sound, for which they limit the amount of sawari they apply. The width of the frets is about one centimeter, and when the string is pressed firmly to the fret surface at one point like is done with a guitar, you get a beautifully clear guitar-like sound with no sawari effect. The frets are made of wood, so you can shave them down yourself to adjust the size of the gap between them and the strings, and the place on the frets that the strings will contact when you push them down, etc., in order to get the kind of sound you want. For that reason, different biwa performers get different sounds from their instrument. I also think that the sound they choose is the sound that fits their voice best. There are people who have muffled voices and people with buzzy voices. Since I have a voice with a nasal sound, I don’t really like sounds that are too expressively showy, and I also don’t like that are too shark in tone. I feel that the quality of voice I produce and the quality of the tone my biwa produces have become more and more in harmony, and I think that is an important part of our art that involves singing a story and playing our own accompaniment as we sing. I all of us performers hope that, rather than whose biwa we might like to sing to, we all hope that the sound we create with our own biwa will suit our singing best. - Now, besides performance activities with the Satsuma Biwa, you are also playing with a progressive avant-garde band and other activities. You also give performances of new interpretations of the biwa classics as well as original new pieces you have composed, and your staging is often unique. Due to the restrictions imposed by the coronavirus pandemic, you have also posted performances online, including a solo performance of YOSHITUNE MANGA at the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media that uses avant-garde film in the background and a combination of classic Satsuma Biwa and experimental noise music. At the beginning and at the end of this performance you play the classic piece in the Biwa-uta style (singing the narrative recitation while accompanying oneself on the biwa), and in between those parts you do things like laying your biwa down and using it as a sort of sound apparatus and creating unusual visuals with Licca-chan dolls along with a Thereminvox-like device creating noise music.

- The band was something that resulted from an invitation to join in on a program celebrating the 30th anniversary of Radio France. A friend of mine, the cellist Gaspar Claus did the setting and we were joined by a guitarist to form a band of three named KINTSUGI. I went to France and that was when I learned for the first time that the theme we were to work with was “love,” so I thought about things from the Biwa-uta repertory that could fit this theme. Although most of the pieces in that repertory are records of ancient wars where heroes are dying, I remembered that in the piece “Yoshitsune” (The fugitive general Minamoto) there is a scene where he parts with his beloved concubine Shizukagozen. In that scene, Yoshitsune (who is fleeing the wrath of his older brother the Shogun) is forced to seek shelter in a holy mountain that women are forbidden to enter, and as he parts with her, he says, “Let us meet again in the next life,” before the share a last cup of wine. Gaspar agreed that this would be a good piece to use and we set to work on an arrangement.

In order to create a performance consisting of three pieces of just under 20 minutes each, we worked out arrangements for the cello, guitar and biwa, and we also decided to worked in noise segments. Since it would be hard to bring in real substance to the pieces if we all didn’t know the contents of the original piece itself, we held a study session about what kind of historical character Yoshitsune was. From there, we contributed our opinions to work out phrases for each of the scenes and the emotions they represented and finally created a 1-hour work. There was a long free session after I finished my recitation part, there was a solo part in which I sought to express the sad period from the time Yoshitsune went into hiding until his life ended in tragic death. This turned out to be a successful performance that lead to the KINTSUGI tour that has continued for three or four years. We went to a lot of places around France from Paris to small country towns that had little more than a bakery and a drug store. There was a great reaction whenever the noise kicked in, and we hung lots of Licca-chan dolls rigged to emit different sounds whenever they changed the angles of their hands, which people found very fascinating as well. - What gave you the idea to use the biwa as a sound apparatus rather than in its traditional performance role?

- At first we used a guitar effector to create a variety of sounds, but before long we found that wasn’t enough. I have a sound apparatus that a musician friend gave me, and when I connect my biwa to it I can get a sort of cosmic sound, and when I manipulate it with the fingers the tonality of that part changes to create interesting effects. Deep on the bridge where the lower ends of the strings are attached is an acoustic hole called the ingetsu (hiding moon), and that is where we attach the microphone to pick up the sound. That sound is then run through the effector. And because of that, the increase in devices brought an increase in the variation of noise that was being produced. If you have one computer you can do anything, but for me it is very important to have gadgets (to make sound). Gadgets are very analog in nature, and that makes them very well suited to the biwa. So, I collect gadgets one after another, and now it feels as if I have literally a fortress of them around me when I perform. (laughs)

- Why do you feel it is that gadgets are well suited to the biwa?

- The biwa is also very analog, isn’t it? The strings are made of silk. There are also nylon strings, but they are tasteless. The silk strings are bound threads, so they change on tone when the humidity changes, which is a bother, like a selfish cat that is picky about what it will eat; it just won’t be obedient. Even the lighting in a performance venue hitting the strings directly can change their tuning so the player has to quickly make adjustments. It is difficult to string the instrument effectively. Some people try to alleviate these problems by using nylon strings. Since humidity changes had no effect on Nylon strings they can be used for outdoor performances as well. The reason I don’t do that is because I find an appeal in things that contemporary society finds completely bothersome. They require effort and that takes time. But that is exactly why they have value.

The biwa world is one of measured timing, or ma in Japanese, it is not a music al form defined by “beat.” It is not timing that can be measured by a metronome but timing that bases expressiveness on a more ambiguous or uncertain measure of deliberate delay or urgency, and for that reason it is OK for performers to delay or quicken the interval between notes as much as they want. That interval of time between one note, one sound, can even be something like four hours. If a performer can hold a concentrated tension throughout a piece, it automatically emerges as a performance that will stand as a solid piece of music. Even if the performance goes on into the following day, I believe this is a world that is OK, as long as that threat of concentrated tension remains unbroken. In this world of performance where light attempts at presentation just don’t fit in.

In Japanese we say that the strength of the biwa is something we refer to as zatsumi, which can translate as [deliberate] “off-flavor” or “odd taste.” We deliberately add the buzzy sawari sound. It seems that for many Europeans it sounds like an unpleasant sound, and the French especially seem to dislike that type of medium-tone domain. In France, when I delivered a real full-voiced medium-tone vocal that is unique to traditional Japanese hogaku music in a performance it apparently sounded so bad to the PA sound technician that he changed the changed the sound without my consent. When I did a live performance once in France, I had a cold and could only deliver half of my normal voice but, conversely, the audience loved it. The PA told me how great it was and easy it had been to work with (laughs). It appeared that just half of my normal performance voice was just right for the French audience. It is surely a cultural difference, I guess. - Was it these unique elements so different from Western music like ma (measured timing), ambiguity and this zatsumi, that initially attracted you to the biwa?

- I guess it might have fit well with the rebellious spirit I always had from the time I was a child (laughs). To tell the truth, I wanted to quit it every day, but it has now been 30-some years. I was always one that easily got tired of things and quit the things I started, so if the biwa was something that went as I thought it would from the start, I probably would have quit it after three days. The reason I don’t get tired of the biwa is probably because it never goes as I expect, and there are times when nothing goes well at first, and there are such drastic ups and downs between times when things go well and times when they don’t. I guess I am just fascinated with the way I remain at the mercy of this instrument.

- The songs of the Biwa-uta (songs sung to the biwa) repertory tell stories. It would seem that the interpretations of these stories would differ by performer. Are there things that the master tell the apprentice about the interpretation.

- You can read the historical narratives like the Heike Monogatari (The Tale of the Heike), and at first read the books and studied history. History isn’t a subject that I like much. But people think I must be so well schooled in the details of the historical narrative that they say how moved they are by my singing, or that listening to the stories brings tears to their eyes. But as for myself, I am not really thinking about the stories but about the technical aspects of the performance. For a sad scene in the narrative, I think about what kind of vocal color I should use or what kind of sound will create a feeling of sadness. But if one tries to put too much emotion into the performance, it sounds bad, because the essence of the biwa is stoicism.

What I was taught by my masters about this stoic aspect is that one should never look at the audience. If you look at the audience, your personal feelings will come out, but if you close your eyes you will get too absorbed in yourself and get carried away in personal obsession. We are taught the art of the biwa is one in which you lose the self, like the eyes-half-closed state portrayed in Buddha statues looking downward over all things with detachment. In Biwa-uta, you become the detached storyteller maintaining a broad overview of everything, but there are also times when you suddenly become one of the characters in the story. You may suddenly become the tragic character Yoshitsune and recite with his voice in first person. Since you have to play the three roles of [biwa] performer, narrator and [story] character, we are told that we must be careful not to inject too much emotion [into any one of the three]. Still, there are some performers who love the narrative so much that, in their performance, when reciting the role of Yoshitsune they act it out with emotion, but I never do that.

So, how do you express the emotions of the narrative? I recite Yoshitsune’s words in the narrative as if I am Yoshitsune speaking, or I recite the part of Yoshitsune’s servant Benkei in the Kanjinchō scene, and of course when I do, I get pictures of the scenes in my mind. But, when I think about how to act that parts, what kind of voice to use and in what volume and how much to imitate a crying voice in such a role, I am doing it from the perspective of technique, so I don’t actually cry. So, I can immediately return to the narrative. When practicing, it is done in front of a mirror so I can see how my posture looks and if that biwa is at too much of an angle so I know if the overall form looks good, if there are any wrinkles in my brow and check that there is no visible tension in my face. Then I can act a role of madness while maintaining my calm. That is the most interesting part of reciting a story. - I wonder if there are specific things you were taught about the interpretation of the stories, the staging and how to express things musically, With Shakespeare for example, in plays like Romeo and Juliet depending on what points you focus on and how you interpret the story can give an audience a complete different impression of the same story.

- Well, generally speaking, we are taught about the contents and the emotions, state of mind and such for these stories. Though it can be interesting if you do something wild in terms of the interpretation, usually it is not accepted in the traditional schools if you deviate too much from the accepted norm. We are told that “the tradition is the universe.” You will understand what is good about the biwa if you listen to traditional works. I want it to keep it in a state where if you hear one complete [and correctly performed] classic work, people will understand the strength and appeal of the biwa. So I feel that if you want to do something with a harsh sort of staging or something crazy, you should do in an original or creative new work, not in one of the classics.

I don’t want to violate the value of the biwa or that perfect beauty of the biwa that mater Tsuruta taught me. I want to pass on the unique world of biwa that master Tsuruta created as it is. That may start from copying the master, but I think that can’t be avoided. If you spend time to create your own interpretation of a work, even though the words of the narrative remain the same, the ma (measured timing) with which you play and the difference in intonation of your voice will make the feeling of the piece completely different. Technique can be used to change it in so many ways.

However, emotions like that sadness when someone is killed or loneliness one feels when parting with a loved one, or the desolate feeling when one has to go into hiding are universal human emotions felt by the majority of people, so that is how I perform them. If you go too far in such cases, it feels like an insult to our human emotions. I don’t want to insult the biwa or the art of the biwa musical tradition, so that is where I draw the line. But I think there is room for interpretation in areas such as whether or not Yoshitsune really loved Shizukagozen as deeply as some believe. But that is not what most people want to hear. So I perform the story in a way that fits most people’s emotional expectations.

And for that very reason, when I do my own original pieces, I want don’t want to be confined to those normal emotional expectations. It might even be an attitude like, “Who cares if humanity goes extinct? (Laughs) In my original works I want to perform as I feel at that time and place, feeling free about what sounds I bring together, so any sound or noise is possible. - Was the practice of performing on the biwa while it is laid flat on the floor something that you started?

- I wonder. Because I am the only biwa performer who uses noise or Electronica. It was really just by chance that I started laying it down on the floor to perform, perhaps because the instrument itself is heavy and it got in the way when I was operating the sound gadgets connected to it. I thought that if it was laid down I could play it like the Japanese koto harp, so there wasn’t really any deep meaning behind the decision to use it that way.

In my pieces consisting of noise, I don’t approach them as simply an uncontrolled flow but as musical compositions that follow the basic format of introduction, development, twist and conclusion. There are some noise musicians who are primarily concerned with too much explosive sound and others who have no limits in terms of the length of a work, but that doesn’t suit me. I like quieter noise like the sound of a refrigerator’s motor, the sound of a kitchen ventilator or a baby crying in the distance. I feel all of these have a musical aspect, and they are all sounds that go well with the biwa. When performing on stage, you can’t hear any ambient sounds, the audience becomes quiet, but when there are naturally occurring sounds from the life environment, it becomes a collaboration session with those sounds. It can be a session with the sound of insects chirping, with the wind or with the sound of thunder. I have a strong preference for low-volume noise, and I use it in my original pieces, but when I get out on stage the volume can be raise to the point that it becomes blasting noise (laughs). Take the sound of 600 cockroaches bustling around, when you listen to it just as sound it can sound like the rippling of water in a stream. The sounds of nature are beautiful.

When it comes to sound, there is something like a permutation of what is pleasing. I have a set of rules within me, such as right now I don’t like this sound, or at the very start I don’t want to use this sound. I make it a rule to find a state where this particular sound is the only one I can imagine using. That is something that I want to be strictly devoted to. It is something that has no meaning for most people, so they don’t understand it (laughs). Even though interpretations are different for different people and you should be able to just enjoy that diversity, most people try to make things too difficult. I want to have people just be free and surrender themselves to a world of strange sounds so they can enjoy new experiences. - Looking forward, where do you want to take your biwa from here?

- I want to do things very, very far at the cutting edge. Like the big advances in IT, I wonder if I can’t take the biwa so far to the forefront, so cutting edge that it feels as if computers are old-fashioned. If something doesn’t change, there will be no growth in the number of new performers, and the biwa will eventually die out. But, for some reason, I am getting commissions for big new works, so lately I feel that there is a bit of new wind in the sails for the biwa. I personally tend to be a stay-at-home, I don’t go out much at all and spend most of my time at home, cleaning house and making art objects and playing music, so my life hasn’t really changed much since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic. But in the meantime, the pandemic has really changed people’s feeling and lives, and the biwa world seems to be linked somehow to people’s sense of crisis and the sense of being at the threshold of death, so I feel that there are more people now how are receptive to the sound of the biwa.

- Could it feel like some kind natural cycle or a return to nature? By the way, you have patterns drawn on your head, face and arms and legs. Are they tattoos?

- They are all tattoos. And since I only have them on parts of the body that are normally exposed and visible, it’s the opposite of what most people do (laughs). I began getting them from about seven years ago. The first one I had done was on my chin. At the time I was into Western culture of Europe and America, where about 70% of people have tattoos, and I thought it was cool the way artists had tattoos with innovative designs. One tattoo artist who was dedicated to keeping traditional Japanese tattoo art alive was looking for models, and seeing that I had a tattoo on my chin he asked me if he could give me more tattoos. So he gave me tattoos in a style called Jomon tribal on my feet and right hand that is derived from the patterns seen on Jomon era earthenware, and on my left hand he did an Ainu style pattern. I personally don’t have any obsession with the Jomon period or the Ainu race, but these are designs that had meaning to the tattoo artist. (laughs)

It is my hope to see the prejudice against people with tattoos to disappear. In Japan, few people have tattoos, so we how do stand out, and often people here stare at me from head to toe. Well, I’m used to it by now, but I don’t like it. Overseas it doesn’t matter whether you have tattoos or not, and they look at you the same. Two years ago when I went to the Warsaw Autumn contemporary music festival, which has a 60-year history, I was the first Satsuma biwa performer ever to be invited to it. My performance was with an orchestra, and I played the opening part as a solo, and as soon as I hit the first strong note (bang!) on the biwa to break the silence, the audience stayed still and concentrated on the music, and when the performance was over we got a standing ovations that went on and on. The festival’s director came back to the dressing room after and congratulated me, saying happily that he had never seen such and excited response. - I have looked at the “Kakushin TV” broadcast that you have on the Internet. What I saw impressed me with how much you love the biwa and that you want to communicate that to as many people as possible. Don’t you have the desire to realize your late master Kinshi’s [Tsuruta] dream of forming a biwa band?

- I think it would be interesting if I had apprentices who wanted to do noise with me, but it is hard to find any. It is tough because it may sound like I’m setting a special standard for myself, but since the biwa is an instrument that goes hand in hand with the Biwa-uta (narrative singing) traditions, I want my apprentices to do both the playing and the singing. I can’t accept people as apprentices who want to take a half-hearted approach and just do a bit of the singing or just a bit of playing the biwa.

It is not just with regard to the biwa, but I’m beginning to think that there may not be anyone on earth who will find affinity with the things I am doing. It may be that, more than being a musician, I may want to be closer to an activist. In my life, I am always thinking about things like vegetarianism, or environmentalism or the relationship between people who are exploited and those who profit from that exploitation, but I think most people don’t think about these problems, it seems like they go through life avoiding such problems. Although I may be criticized and have to bear the brunt of my actions, I just can’t help the fact that I am the type that has to do what I think is right. There are so many problems that have to be faced, like child suicide and the problems of the poor, and though I feel they all need attention, I only have one body, and I don’t know how long I will live. I don’t like people all that much, but when I see people who are struggling with such inconsistencies it makes me wonder if that is right. So, if people come to know about me from the biwa and if among them there is even one person in one hundred that my words touch, that is enough for me.

Maybe in ten or twenty years there will be people who will say the things I was doing are interesting. By that time I may be retired , or I may be doing something different, but I think that is OK. - Listening to the things you say, the word compassion comes to mind, and I wonder if the more you work with the biwa, the more you are drawn into the world view of having the biwa, the world view of loving nature, the world view of loving people.

- Well, there is a world that the biwa carries with it, like the tradition of mourning for the deceased. As an instrument, the biwa has lived with the same body, the same form for hundreds of years and it has been passed down by the hands of many different people, it has been used by priests to quell the spirits, and it bears all of that history. Today I am feeling the limitations of speaking only through music, and I am searching for a way to deal with this as an activist.

While carrying on the tradition of the classics and writing pieces with the techniques of the tradition, I am also writing pieces that are a sort of culmination of the voice of my biwa and the voice of Western music (chorus) and noise and everything, but I don’t think of this as work that will classify as a new form of biwa art. I believe it includes writing original noise music that contains none of traditional classics or the biwa and facing the problems I see before me as an activist through my Kakushin TV.

Earliest encounters with music and the Satsuma Biwa

The state reached by learning from two teachers

Collaborations and Original Works

The biwa Japanese lute, a stringed instrument. Said to have originated in Iran or Arabia and reached China in the 7th or 8th century. In Japan it was traditionally used in performing ritual music and Gagaku (the court music of Japan since ancient times), while its use also spread as blind Buddhist priests played it while reciting scripture, and among the general public for reciting folk tales as entertainment. Especially popular among these historical folk stories was the Heike Monogatari (The Tale of the Heike). Biwa instruments for use in music include the Satsuma Biwa that emerged in the 15th century and the Chikuzen Biwa appearing in the Meiji Period (19th century). There are slight differences between the instruments, but they basically have a slender neck connected smoothly to the body, which has a shape that bulges toward that bottom similar to an eggplant, and the bridge to which the strings are attached curves backward. There are four strings on the most biwa but five on the Tsuruta school biwa (with two tuned to the same note).