- You were born in Kashiwazaki, Niigata Pref., and we hear that you dropped out of high school and came to Tokyo originally with the aim of becoming a chef. Can you tell us in some more detail what you did before turning to theater?

- My father was a landscape gardener who also painted, played music and rode motorcycles, and I feel that I was greatly influenced by having a father like that. I liked cooking and worked part-time as a cook when I was in high school, and from around the middle of my freshman year I began skipping school to ride around on a motorcycle. I finally reached the point where school just didn’t suit me anymore and I ended up dropping out after the first semester of my second year of high school. After that I would work at part-time jobs until I saved up enough money to go off traveling.

- Where did you travel? Did you travel around to the far corners of Japan?

- Not really to the far corners, I was actually rather haphazard in my choice of destinations; I never went to [the northern island] Hokkaido, for example. I didn’t go to [the southern island] Kyushu either. For some reason I just went here and there around [the main island] Honshu (laughs). But I did a pretty thorough job of getting to all the prefectures of Honshu except Yamaguchi. And I walked the pilgrim’s trail full circle around the island of Shikoku when I was in university.

- After coming to Tokyo with the intention of becoming a chef, how did you end up entering theater?

- I worked in the restaurant industry for about half a year, and I got a cook’s license with the aim of becoming a chef. Around that time I was influenced by my older brother, who is what you might call an intellectual, and he inspired me to begin reading book, which I hadn’t done until then. I realized that mangas and movies wasn’t enough. The only ideas I had about what to read was that foreign literature seemed a bit cooler to read than Japanese literature (laughs), so I went to the used book stores and bought sets of Iwanami classics and just read and read.

I didn’t have any friends in Tokyo at the time, so I was just working and spending all my free time reading until a friend of my brother’s said, “If you like to study, why don’t you take a university entrance exam that you can take even if you haven’t finished high school. So I went to a cram school for a while and passed the test to get into the university. When I dropped out of high school my parents virtually disowned me, but when I got accepted to university they were suddenly more than happy to pay my tuition (laughs). - During those times of traveling and training as a chef and reading literature, what was in your mind most of the time?

- I read a lot of books concerning Buddhism and I was attracted to Zen thought. When I was traveling around the country on my motorcycle, I often stopped at little-known local temples. I could sleep out there for free, and I often had the opportunity to talk with the priests. Many times I found myself being impressed with the things they had to say. I also liked Buddhist architecture and Buddhist art, and I found the Buddhist sculptures and temples of the Shingon sect of Tantric Buddhism to be especially cool (laughs). At the time Jun Miura and Seikou Ito were writing a series of articles in magazines about the traveling around and observing Buddhist sculptures in the various regions of the country from their own interesting perspectives under the title “Ken butsu ki” (Diary of observing Buddhist Sculptures), and that was close to what I was doing and feeling too. It was not like I was interested in Buddhism from the standpoint of a believer, but like some people find the monsters in the “Kamen rider” and “Ultraman” series cool, I would find myself thinking things like, “The Thousand-handed Kannon sculpture at such-and-such a temple is really cool!” That’s why you will still find things like that coming out in the plays I write today.

I also felt an affinity for the American Beat Generation writers and their movement of counterculture. Perhaps I like them because a lot of the works of the generation were influenced by Zen. - Can you tell us about the process you went through going to the philosophy department of Toyo University and then eventually getting involved in theater?

- At first I thought I wanted to make movies, so I entered the film club at university. It was just around the time when moviemakers were switching from film to video, and since video was cheaper and you could make more mistakes without big cost, I wanted to use video. But the film club had a thing about using only film. So I decided to do it on my own, so all four years of university I would work at side jobs and save up money to use on making video films with friends I gathered for each project. But I couldn’t keep it up for long because the common practice with self-financed movies was for the director [me] to pay for everything, from the actors’ box lunches to transportation fees.

After I graduated and was just knocking around, an actor who had acted for me in one of my movies was acting in a play by the Tokyo 23 Kugai Theater Company and I went to see it. I didn’t have any real interest in theater at the time but I was curious about how theater companies like that managed to put on plays, the financial side of it. So I asked them and was surprised to find out that they all put up money together to pay for the theater and staff fees and then each actor sold a certain quota of tickets, so in the end they are able to mount a production with the cost of only a few hundred dollars to each of the members of the company. It’s an amazing system, isn’t it? The actors don’t get paid to perform, they are made to pay from their own pockets to perform. Isn’t it something? (Laughs) So I said, “If that’s all it takes, then let me write a play.” That’s how I got into theater.

The first play I wrote was never performed, and they told me I should try experiencing theater as an actor once. They told me that would help me see the flow of the process by which a play comes together; you have the actors, the director, you have the script, the staff work and then you put it together in the theater. I tried it, but it didn’t suit me, or perhaps I couldn’t accept the fact that I was being made to do it. Anyway, it didn’t work. So I went into writing and directing, and eventually in 2003 I got together with a few members of that theater company and formed a new company named “Ikiume.” - You bring elements of science fiction, horror and the occult into your plays. For example, your latest work is a four-part omnibus titled Toshokan-teki Jinsei Vol. 2 Tate to Hoko (A Library-like Life Vol. 2 Shield and Lance). In that title, there are Moja (The Dead) in which the [spirits of the] dead waiting on the shores of the river to the other world are forced to do menial labor by a middle manager-like demon in order to get into heaven, and Kaiseki (Ceremonial Meal) where a couple takes in a young man who has been assaulted by thugs and because of their inherent goodness allow themselves to come under the control of the youth, and Kofuku (Happiness) where aliens plan to take over the world with a secret weapon (when people look at it they are overcome with a bliss that is ultimately fatal), and Teio (Emperor) about a man whose emotions are expressed not as facial expressions but as relations that move the muscles of his whole body. All of them are full of unique Maekawa essence.

- This isn’t something I was doing consciously from the beginning, and I guess I didn’t recognize it until people around me pointed it out. Looking back, I definitely was a kid who liked ghost stories and monsters, and I liked the atmosphere of temples and shrines. I especially liked Shigeru Mizuki’s Yokai daihyakka (Encyclopedia of Ghosts and Demons). The 110-year-old elementary school I went to had a lot of stories about ghosts haunting it, and I edited a “Ghost Newspaper” as a kid when I was at the elementary school. My interest and preference for these things are definitely at the root of my works.

- Science should be able to explain most of the natural phenomenon of the universe, but we are not yet at the point where science can explain it all. There are still things that can’t be explained, and it is very interesting when you look at ghosts and the occult from that perspective.

- I think so too. Religion just takes over where science leaves off, or the unexplained realms are just explained with the occult logic of the devil and curses. And doesn’t that mean that you can use your imagination and make up your own explanations for things in the realm that science can’t explain? That’s why when we formed our company Ikiume, I wanted to create works in which I could insert lots of my own interpretations of the things that everyone finds mysterious in stories made of those explanations. I thought that would be a really adventurous and rewarding form of writing. I though it would be great if I could write things that would make people say, “Yes, that is a wild but possible explanation or interpretation. In other words, writing stories that I could fill with believable lies.

- But if you are taking that kind of approach consciously, don’t you reach a point where it becomes a form of limitation to your creativity?

- That is an element that does indeed come out. When I say that I like science fiction and the occult, there are actually not such a large number of things in those genre that I really like. And now that I have been writing that way for two or three years, I am now feeling that I have already touched on a lot of the things that interested me. Until now I have been writing more or less in a style based on ideas of what I think would be interesting as an [unexpected] occurrence in a story, but now I am thinking that more can be done with those same ideas, rather than just writing something as a horror story, I could write it in a way that connects more to the real world.

- You were born in 1974 and are thus of the same generation as the playwright/directors Keishi Nagatsuka and Daisuke Miura . What do you feel are the traits that characterize your generation and its social background?

- The education our generation got at school was always focused on individuality. It was as if we were constantly being told to find ways to express our own individuality and I believe that we are a generation for whom that kind of individualistic approach to life was being forced on us unnecessarily. That’s probably why there is a tendency for our generation to be obsessed with pursuing a creative lifestyle, or reacting by not going anywhere and becoming a NEET, or to constantly be changing jobs in search of a career that better suits their own nature. I am interested in the consciousness of our generation and the way we view ourselves.

Also, there are so many crazy incidents like the recent multiple killing spree by a man of our generation in the Akihabara [geek] district of Tokyo are happening around us. But, no matter how much you watch the coverage on television you don’t get a picture of the background behind such incidents. There have also been a lot of incidents of deceitful labeling of foods by companies that certainly weren’t corrupt when they started out, but somewhere along the way they crossed a line and ended up engaging in these unbelievable illegitimate practices, or incidents, as in the case of the Akihabara man, caused by some build-up of stress of frustration causes people to cross a line and commit these acts. I am very much interested and concerned about the backgrounds of these incidents where people cross over into unforgivable actions, and I am now involved in gathering data about them. - The word ikiume in your company’s name is said to be a name that comes from the concept of getting glimpses of the other world [the afterlife] while still alive. From the word ikiume we can also get a sense of a stifling era where people are “buried alive” in the restrictions of society. What exactly does the “other world” (higan = “the other shore,” or Buddhist Nirvana) in this concept imply or express? Is it the relieved happiness of a Buddhist heaven (seiho jodo = Paradise of the West), or is it a hell of punishment?

- No. It is neither a heaven nor a hell. It is called the “other world [other shore] exactly because there are no words besides “other” to describe it. If one was forced to choose between heaven or hell to describe it, it is closer to heaven perhaps, but not in the sense of a joyous or pleasurable world. Rather in the sense of “a place of importance.” It does not carry a religious significance but it does imply a sense of the most important and final goal of life.

Through my stories [plays] I want the audience to have an encounter with that idea. I don’t care whether you call it, but I want the people who come to the theater to have an experience of touching, if only for a moment, the underlying essence behind our lives that make it as it is. - One of your works, Sampo suru shinryakusha (Strolling Invader), which premiered in 2005 and you also rewrote as a short novel, is about an alien that is able to enter the bodies and minds of humans, and in order to research the human race, the alien gradually removes certain concepts, such as “family” and “laughter,” from the minds of people it meets. And through this device, you depict people who have been possessed by the alien and people who deteriorate as they are stripped of various concepts and the truths that are revealed in this process—all of which you present in a comical style. What kind of “other world” did you attempt to portray in this work?

- I began writing that work out of an interest in what type of existence a person who had been possessed by an alien would have. The human being that has become “pawn” of an alien invasion retains his memories in the form of information in a body into which the alien has been installed like a form of software. He continues to function as a human with the information he has acquired in his life up until that point, but that becomes meaningless as the alien that has entered him robs other humans of concepts and in doing so gradually changes their character. And then finally, when the concept of “love” is taken from them they realize what the true nature of the human being is…. I wrote this work with the desire to think about what makes human beings human.

Listening to you talk about your works, it sounds like you start out with a big question mark and then gradually break it down. It seems like you start in a situation where you don’t know whether or not you will arrive at an answer in the end but you keep writing with the material you have before you. Is that it?

- Yes. He first step is to find just how strange or wondrous a question mark I can put up there, then the next step is to look at that question mark from a number of perspectives, and if I can make up some angle that is interesting I consider it a success.

With Sampo suru shinryakusha (Strolling Invader), the idea developed out of a story I had written earlier. It was a story about a young Japanese who went to America to study but developed a fear of going out and was paralyzed by his fear to the point where he couldn’t set foot outside his apartment. Three friends came from Japan to help him, but they too became terrified of going outside. There were able to get food by home deliveries and they were able to do their shopping through the Internet, they also got the information they needed from the TV. In the course of time they reach a point where it no longer matters to them whether they are in Japan or in New York.

If their window to society is the Internet and TV then there is nothing different from being in Japan. If that is true then where are we really? And that means that the concept of “nation” is being lost. So I ask myself how they will talk once they have lost the concept of country, how will they talk when America and Japan are just the names of things, not nations? How will people change when they lose a variety of concepts like that? The development of interest in these questions is what led me to the idea that I explored by writing Sampo suru shinryakusha.

Then I asked myself who should be the ones that steal the concepts from people’s minds? The answer that came to mind is that aliens would be best (laughs). When thinking next about what kind of aliens it should be, I remembered the character Metron Seijin (alien from planet Metron) from the Ultra Seven story Nerawareta machi (Targeted Town) (laughs). [Ultra Seven is a TV series from the 1960s filmed in special-effects style. In this popular series the hero Ultraman Seven has come from outer space to defend the Earth from alien invaders and monsters].

This Metron Seijin character makes its base of operations a cheap apartment in a small country town and puts a poison in the cigarettes in the vending machines in front of train stations that caused people to go crazy and kill each other. And in this way it plans to conquer Earth. But why a cheap apartment in a small country town, and why does it put the poison in one particular brand of cigarettes?

Probably the aliens from planet Metron did their research and found that there was no need for them to bring in their weapons and fight the humans because they are a race that can’t keep negative feelings from building up inside them and, as a result, once they start a war they can’t stop it. So, it would suffice just to start them killing each other. Of course this is just my own interpretation, but that image of the Metron Seijin led to the alien character in Sampo suru shinryakusha. In appearance, the Metron Seijin looked something like a goldfish, don’t you think? And that is why in Sampo suru shinryakusha the first creature that the Metron Seijin enters is a goldfish. But that is the only Metron Seijin episode that comes directly from Ultra Seven (laughs).

At the end of the Ultra Seven story Nerawareta machi, there is a famous scene where the hero Ultra Seven and Metron Seijin face each other across the kotatsu (heater table) in the small 6-mat single-room apartment and talk about peace for Earth and the universe. That scene was really cool and remembering it made me think that I could use the device of this alien that steals concepts from people’s minds and have it sit at the kotatsu and talk about peace in the universe and love. That was a main motivation for writing Sampo suru shinryakusha—if it’s OK to let them talk that way, then really let them have a say.- You started out making movies, but when you switched to theater was there any artist who influenced you?

- When I first started out in theater I went around and saw a lot of plays, but when I did I was only really looking at what the plays were trying to say. I wasn’t looking at the plays as theater. For me, I first have a story that I want to tell, and my media just happened to become theater by chance really. So, in the end, it is the story that is most important for me.

- There is a methodology by which the writer/director takes into consideration various theatrical effects from the beginning and arranges the plot development in a form similar to a maze. What do you think of that kind of approach?

- There was a period when I was thinking that way. Like a complex plot development is cooler or more sophisticated (laughs). But I believe that it is meaningless if it doesn’t get your message across. Now I think a play is stronger if it communicates its message directly and powerfully, without unnecessary twists in the plot.

- It seems to me that in your plays, even if the setting is one of a broken-down social structure or pattern of events, the interpersonal relationships have not broken down; there is still trust in the relationships or a sense of brotherhood. This appears to stand in contrast to the other playwrights of your generation who write about broken down human relations or the solitude or loneliness of the contemporary human state. Where does your sense of human relations come from?

- Is that so? You feel a sense of human trust (laughs)? Personally, I had a stammer when I was young and, partly because of that, was never especially good at interpersonal relationships. I tend to be shy with people I meet for the first time, and I don’t talk much. But, I have been aware of that and have made a conscious effort to overcome those traits and try to talk more. I have never thought about were my trust in people comes from, but I do think it is one of the traits I have perhaps more strongly than some people. It is not necessarily that I believe we are born with human nature is inherently good (seizensetsu = Confucian concept of inherent human goodness) but that I want to believe in people, that when the time comes they will do the right thing. Also, I have almost no desire to bring all of the uglier sides of human nature to the stage. Of course, I think it is fine that there be works that present the uglier sides of human nature out in ways that the audience finds truly relevant and become absorbed in, but that is just not what I am interested in.

- Yes. He first step is to find just how strange or wondrous a question mark I can put up there, then the next step is to look at that question mark from a number of perspectives, and if I can make up some angle that is interesting I consider it a success.

Tomohiro Maekawa

Weaving a thread of the supernatural into the daily lives of the young generation

The world of playwright Tomohiro Maekawa and his theater company Ikiume

Photo: Akihito Abe

Tomohiro Maekawa

Playwright and director Tomohiro Maekawa was born in Kashiwazaki, Niigata Prefecture, in 1974. After graduating with a in philosophy from Toyo University, he founded his theater company and the base for his activities, Ikiume, in 2003. His unique style incorporating elements of science fiction, philosophy, and the occult has attracted much attention and acclaim.

Internationally, productions of his work are increasing. Maekawa’s work was performed in Seoul by Korean actors, first in 2019 with Strolling Invader, followed by The Sun in 2021. When The Sun was then restaged at the National Jeongdong Theater in 2023, a dance piece of the same name was also performed.

In 2021, Ikiume staged À la marge in Paris to critical acclaim. In recent years, his plays continue to be published in a variety of languages, including French, Korean, Spanish, English, Russian, Arabic, and Chinese.

Maekawa has won several prizes in Japan, most recently the Excellence Award at the 31st Yomiuri Theater Awards for To Deliver a Soul, which was staged in 2023. (Updated April 2024)

Interviewer: Hirofumi Okano

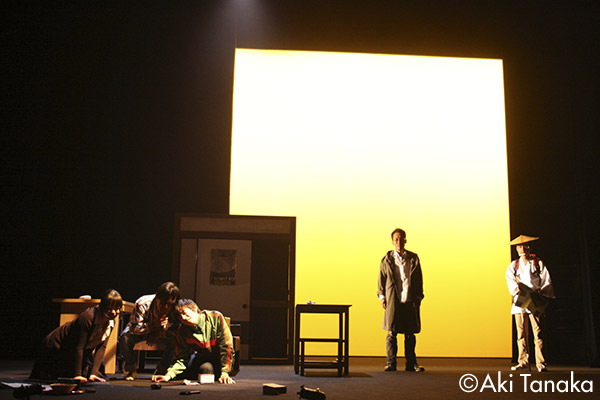

Ikiume Toshokan-teki Jinsei Vol. 2 Tate to Hoko (A Library-like Life Vol. 2 Shield and Lance)

(Oct. – Nov. 2008 at Mitaka City Arts Center)

Photo: Aki Tanaka

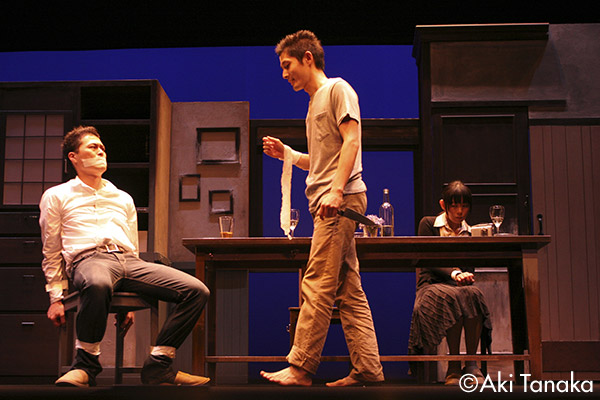

Ikiume Sampo suru shinryakusha (Strolling Invader)

(Sep. 2007 at Aoyama Round Theatre)

Photo: Aki Tanaka

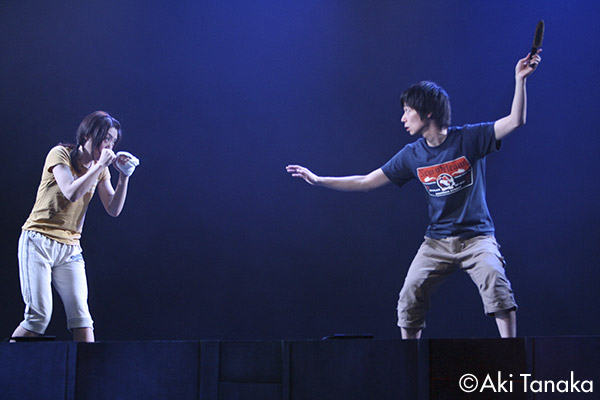

Ikiume Omote to ura to, sono mukou (Outside In, and Out There)

(Jul. 2008 at Kinokuniya hall)

Photo: Aki Tanaka

Ikiume Nemuri no tomodachi (A Friend of a Slumber)

(Feb. – Mar. 2008 at AKASAKA RED THEATER)

Photo: Maiko Miyagawa

Related Tags