-

There is a book titled

Kabuki Odogushi

(Kabuki Set Maker) written by the Kabuki set backdrop painter Kumaji Kugimachi at the age of 85 as a memoir of his career. It was just reprinted last year and in preparation for this interview I read it again.

The book tells how Kugimachi gradually changed the former dogucho (set-making notebook), which was the notebook containing little more than sumi ink sketches and written notes that the odogushi (the “set makers” including carpenters, paper [wall] hangers and painters) referred to when making a Kabuki set for a given play. Kugimachi gradually recreated these set-making notebooks into fully illustrated 1/50 scale working blueprint type drawings that came to be known as the Kugimachi style dogucho.

Reading Kugimachi’s memoir Kabuki Odogushi , which begins from the time he entered apprenticeship at the age of ten under the master set painter Kanbe-e Hasegawa XIV in 1912, you get a good idea of how the work of the Kabuki set makers was carried on through the late Meiji, Taisho and Showa periods of the 20th century.

Originally, Kabuki sets were built and painted by craftspeople working as stage crew at each of the small Kabuki theaters and Kanbe-e Hasegawa I, a traditional (shrine) carpenter working in the Nihonbashi district of old Tokyo (Edo) was apparently the first to establish a separate set-making company in 1650, under the Hasegawa name. As I understand it, the Kanai Scene Shop Co., Ltd. ( Kanai Odogu ) that you have now become the 4th-generation president of was established in 1924 by Kugimachi, who until then had worked as a scene painters at Hasegawa, and Yoshitaro Kanai, who also worked at Hasegawa as a master carpenter who had apprenticed under Kanbe-e. -

That’s correct. The profession of the set (

odogu

) maker was already established in the Edo period, and at that time Hasegawa Odogu was the only maker company status. And today, Kanai Scene Shop is the only company carrying on that Hasegawa Odogu tradition. I would add that Hasegawa Odogu is carried on today by the Kabuki-za Butai Co., Ltd. run by Shochiku as the maker of Kabuki sets.

I took over as the 4th president of Kanai Scene Shop when my father (the late Shunichiro Kanai) passed away in 2006 after specializing himself for many years in Kabuki set production. - And how did you become a set designer yourself?

-

There may be a lot of people who grow up in a family like mine and start spending increasing amount of time at the theater from childhood. But to tell you the truth, in my case I didn’t even truly know what my father’s job was until I went to college. It was due to an educational policy that my parents had: not to talk about the theater. In short, it is not like the case of kabuki actors, who have to learn their art from an early age by more or less growing up in the theater. My parents believed that when the time came that I discovered what my father’s profession was and decided I wanted to pursue it too, it would not be too late, and it would be my own decision. So, through elementary, middle and high school I grew up like an average kid and it wasn’t until I went to college that I learned what my father’s job was.

In college, I happened to choose to major in architecture, and that is when I started working part-time at my father’s company. In 1983, I went along with my father when the first Kabuki performance was staged at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. That was my third year in college and I still had no idea what the work of Kabuki set design and production involved. - Did you go along as an official (working) member of the staff?

- I was just what you might call an errand boy (laughs). That was the first time that I really got to see the work of stage set making ( odogu ), and how interesting it could be. After that, I graduated from college and entered my father’s company, Kanai Scene Shop, and when Danjuro (Ishikawa) and Tamasaburo (Bando) took another Kabuki production to the Metropolitan in New York again in 1985, this time I went along as official staff. It turned out that I was part of the team, mainly because I could speak English, and Joe Clark, the Metropolitan’s technical director at the time, asked me if I wanted to come to study under him. With that invitation I was able to get a grant for foreign study from the Agency of Cultural Affairs and spent two years studying and training at the Metropolitan.

- Though we say training, in reality the labor unions are so strong in the American and British theater industries that it is very difficult to get the opportunity to actually work on the front line if you aren’t a union member. Isn’t that true?

-

However, when I got over there and they asked me what I could do, I said I had studied architecture, so I could do blueprints. They gave me some to do and when they saw the results they said they could use me. At the time, the only person at the Metropolitan Opera who was drawing blueprints was Patrick Mark, who was an assistant technical director. So, they immediately put me to work measuring all the sets and making blueprints of them as a means of recording and cataloging the stage art. Those blueprints were then stocked as records of the theater’s productions so that when the productions were restaged the blueprints could be used and minor changes added. And the stock is still being used that way today.

So, you could say that rather than being given a job of my own I was filling in where help was needed, and that turned out to be a fortunate arrangement. Usually a trainee is either just left to watch or asked to help out in menial jobs like filing materials and the like. In my case I was able to join in the meetings and make blueprints from the sketches of some of the leading stage designers of the day. At the time, the Metropolitan had two assistant technical directors, and then there was only Patrick Mark besides them, so it was better for them to have four people working rather than just three. They told me to join in, so by the second year I was being given a production to be in charge of on my own.

After my two-year study period was over they asked me to stay on, but I felt that if I did I would soon be thinking and acting like an American and lose my ability to deal effectively with the Japanese way of doing things, so I returned to Japan, knowing that my links with the States would not be cut completely. - Then you returned to Kanai Scene Shop Co., Ltd. (Kanai Odogu) and began various activities there. Could you tell us something about the company itself?

-

Kanai Scene Shop was founded in 1924 as the set making company for the Ichimura-za Kabuki theater when it recovered from the losses of the Great Kanto Earthquake (1923). Then it went on to establish itself as a maker of sets for traditional theater, including the Kabuki productions at the Meiji-za and Shinbashi Enbujo theater, the

Shinpa

(new style theater) production, the

Shinkokugeki

(modern commercial theater) production and the Shochiku New Comedy theater production.

Then, when television stations began to be established in Japan about 50 years ago, the company began to become involved in producing event and television stages and sets, around the time when my father began to work at the company. Since the odogu (set making) profession existed until then only in theaters, the new television stations began to invite set makers from the theaters like Haiyu-za and Toho Stage Craft Co., Ltd. to come build sets for their TV programs. In fact, our company still gets many commissions for sets from TBS Television.

In terms of organization, the company has three departments, a Theater Dept. that makes sets for theaters including the National Theater, Tokyo, the Shinbashi Enbujo and Mitsukoshi Theater, an Event Dept. handling fashion shows, exhibitions, theme park and contemporary theater and a Television related dept. that handles Television set. Now we have designers for each of these departments. The Event Dept. brings in about 50% of our revenue, and theater sets like Ninagawa director’s new kabuki NINAGAWA Twelfth Night stage are done by this department. Since the construction and methods of expression for Kabuki and other traditional sets are unique, contemporary theater sets are done separately from our Theater Dept. by our Event Dept. While my father was alive, he was the Theater Dept. designer and I was the Event Dept. designer. If I had specialized only in Kabuki like my father, the other pillar of our company would have been ignored and we might not have survived as a company. So, as far as Kabuki was concerned, I only worked on the overseas productions, which have totaled 15 until now. - Even for a respected odogu company like yours, then, you would not have survived had you concentrated only in traditional theater stage art and not expanded into the new areas of television and contemporary theater.

- Today, Kabuki is attracting large audiences again, but there was a hard time when it had less people. Trends are quick-changing these days and you have to expect cyclical changes. If you keep doing just the same thing, you will go down when the trends shift.

- During your years at the company, what have you worked on specifically?

-

The first project I worked on after coming back from the U.S. was the third play of Ennosuke Ichikawa’s “Super Kabuki” (a contemporary Kabuki series created by and starring Ennosuke Ichikawa III that actively introduced elements from Western opera, Peking opera the Japanese small theater scene, etc. Beginning with the first production,

Yamaha Takeru

in 1986, the series has extended to nine productions), which was

Oguri

(1991). One of Ennosuke’s aims was to nurture the next generation of young talent, and since I was just in my early 30s he encouraged me to design the set.

The artistic concept of Ennosuke’s “Super Kabuki” was, above all, to surprise the audience. And since the audiences eyes are the most important, he believed that surprising them visually was the best way. That’s why with Oguri he said he wanted to try using mirrors, which had never been done before in Kabuki. Taking that idea, we discussed the possibilities. With regard to the stage devices, Ennosuke made numerous requests based on the standards of the plays he had done until then.

In his “Super Kabuki” the script was completed a year before the scheduled opening performance. Normally, this amount of leeway is unthinkable, and it gave me plenty of time to work on the details. With the opening scheduled for the following March, I had the plans for the set and props finished by August, and that is when we entered rehearsals. Since the rehearsals are done using a set the actual size and dimensions, the actors also have a chance to fully work up their roles. And the budget we had was unthinkably large by today’s standards. - Even though that was in Japan’s economic “bubble” years when funds were plentiful, it still seems like the ideal way to do theater, doesn’t it?

- Yes. So I used what I had learned in America and was able to take plenty of time to design and make a large-scale set. With “Super Kabuki” I was able to experience ideal teamwork and working methods. The budget was huge compared to an average Kabuki production, so I was able to use a tremendous amount of real water on the set, employ wire work to fly the actors through the air and other special effects. And in that way we were truly able to surprise the audience with a set such as they had never seen in Kabuki before. And the costumes were extravagant, too.

- What is different about the methods of expression used in “Super Kabuki” and those of regular Kabuki?

-

With the exception of the traditional Kabuki acting methods and music used, Super Kabuki can be said to be closer to contemporary theater than to Kabuki in the traditional sense. As a Kabuki actor, Ennosuke always asked himself what kinds of things he would be doing if he were living and acting in the Edo Period. In fact, the people in the Edo Period were always seeking to do something new, so if you translated that spirit into the present with our technological advances, there would be nothing unusual about using mirrors or moving lights. Since the intent and the ideas are the same as in Edo Period Kabuki, so you can say with certainty that this is Kabuki. At the time when Ennosuke began his Super Kabuki there were apparently people inside and outside the Kabuki world who were criticizing him, saying that it was not Kabuki, but Ennosuke was steadfast in his commitment. The encounter with a Kabuki actor and director of such high ideals as Ennosuke was a thing of great importance for me. He is the one who brought me up as a designer.

If I may branch off for a minute, I believe that the reason Broadway theater developed so dynamically is because most of the theaters have stages with no wings to speak of. Since there is no usable wing space, they had to improvise with their stage art and sets. Bigger and wider is not always in theaters. It is often the restrictions of the theater space that lead to creative ideas and progress. It was the same with Super Kabuki. The Shinbashi Enbujo is not such a big theater and that led everyone to take a trial and error approach in improvising new approaches and methods. Ennosuke’s achievement in breathing new life into the Kabuki world with his new approach is truly a great one. I believe that the aggressive new experiments being undertaken by Kabuki actors like Kanzaburo Nakamura XVIII and Kikunosuke Onoe V owe a lot to the pioneering efforts of Ennosuke’s Super Kabuki. - At the time the large number of people coming to see the performances were a major reason for the size of the budget Super Kabuki had, and although the era of the “bubble economy” was one with serious problems, it was also a valuable period, I believe, when it was alright to experiment and perhaps fail at times. Is there anything in particular that you learned at that time about stage art by working with Ennosuke?

-

To begin with, stage art is not just a matter of putting up a beautiful design. The communication with the director, with the other artisans involved in the set-making and with the lighting technicians and the other staff is important. Working within the grand organization and production that was Ennosuke’s Super Kabuki, I learned first-hand that the set and the stage art can’t be successful without communication.

Also, since the realization of theater comes only when it is seen by the audience, I realized that it is not a matter of desktop design based on the dogucho (notebook of set-making diagrams). This may sound like a criticism of Kabuki, but even though the dogucho is only a collection of well defined sketches of what a set design can be, to this day the pre-production planning sessions by the set-maker are conducted only with the dogucho for reference. In the Super Kabuki productions we used scale models of the sets in our meetings, as is the common practice in contemporary theater. Apparently that was the first time that Ennosuke saw the use of scale models in set design, but their use definitely led to new ideas. He said several times that scale models should be used from now on in Kabuki stage design. - Even if they don’t make a colored scale model, they always make at least a white study model in theater set design today. Is it true that in Kabuki they still only use the dogucho ?

- It’s true. But when you are only referring to the dogucho you can’t see the relations between the parts of the set in terms of their position on the stage and you can’t even tell front from back in some cases. That’s why there is often confusion and arguments when a Kabuki set is being put together. The old dogucho are no more than diagrams for making the parts of a set, it is not stage art. It is a set of working drawings. The set maker looks at the dogucho and gets a rough idea and then assigns lengths to each part as he constructs the set, but looking at the dogucho alone will not tell you which parts are to be fully 3-dimensional and which are false-backed (only 3-dimensional on the side facing the audience). The dogucho was a viable resource due to the fact that the person drawing the dogucho and the set makers working from it shared the same understanding of what the finished set would be like in a traditional Kabuki context.

- One can’t help but be impressed with the variety of works you have been involved in as a set designer since Super Kabuki as well.

- After my work on Super Kabuki a lot of offers came to me. And for Kanai Scene Shop as well, the range of set-making jobs we received has broadened, and from the design aspect, the number of non-traditional stage art we are asked to do has increased. Still, there was understandably a strong image of Kanai Scene Shop as a maker of Kabuki sets, and in terms of scene [backdrop] paintings, there was probably an image of us as a shop that could only do Kabuki style backgrounds. It is only in the last ten years that we have become established in the contemporary theater scene as well. A recently example is the set we did for Gekidan Shiki’s production of Phantom of the Opera .

- One of the most noted works you have done recently is with director Yukio Ninagawa ’s NINAGAWA Twelfth Night production in the New Kabuki style at the Kabuki-za theater.

-

At the press conference announcing the start of production

NINAGAWA Twelfth Night

, Ninagawa said that he was putting me in charge of set design as someone who knew the Kabuki-za theater inside-out, but in fact I had never worked at the Kabuki-za. When I told him that afterwards he looked worried and said, “Hey, are you going to be all right?” (Laughs) In other words, for both Ninagawa and myself, it was our first attempt working at the Kabuki-za. And since I didn’t know the Kabuki-za theater, I was determined to work with abandon and see what I could do.

Ninagawa’s request regarding the stage art was that it comply with the basics of Kabuki. He also said that he wanted to use mirrors. Those were his only two requests. However, the way I interpreted “the basics of Kabuki” was not simply using the conventions of Kabuki. My interpretation of “basics” was simply that it not feel odd or uncomfortable as Kabuki.

Not only in Kabuki but in any kind of theater there is an element left to the imagination; that a wall that should be there cannot actually be seen, or that a wall can be seen even though it is physically impossible, that a painting on a flat backdrop depicts a scene that extends far into the distance while props on the stage represent the foreground. There are many conventions like this. And, since these are the only real rules that apply, I read the script and then made scale models for the sets of each of the 14 scenes. It may have actually been a benefit that I didn’t know the Kabuki-za, because I was able to bring in my models and CAD printouts and ask the set makers there, who until then had only worked from dogucho to build the set based on the models and CAD-generated working plans. - CAD-generated working plans may be easy to work from in the sense that they show scale and dimensions clearly, but they must also be a lot of work to make, because all of the details have to be drawn in. The dogucho tradition of the Kabuki world allows for individual expression by the set makers. For example, the makers have used their sense and experience to make slight variations in the size of props or set pieces based on the physical size of the actor or his preferences. But a CAD-generated working plan basically tells the maker to “make it exactly like this.” This makes it difficult to maintain that kind of flexibility. Didn’t your working method cause problems for the theater’s set makers?

-

There was a lot of that. I heard them saying behind me, “What is this supposed to be”? (Laughs) But only the opaque paints used in Kabuki set-making and the set and props were basically the types that can be made by Kabuki set makers. The production process involved a lot of explanation.

Still, I don’t think my father, who concentrated on Kabuki set design all his life, would have thought of an Art Nouveau transom arch, for example. And even for the most experienced of the old guard of Kabuki set makers mirrors are not a material that they know how to use. Although it is not in my realm, the lighting that Tamotsu Harada designed brought moving lights to the Kabuki-za for the first time, and 45 of them at that. That surprised even me. But after that the technicians at the Kabuki-za found them convenient and they are using moving lights regularly now. Performers like Tamasaburo are now using them in their regular performances. - In that sense you may have opened some eyes at Kabuki-za. And it is a good thing if the change is in positive directions.

- I believe it proved that the Kabuki odogu craftsmen and artisans had the ability to work from CAD generated images as well as the dogucho and the skills to create the set we designed.

- You have also worked with Kanzaburo [Nakamura] and the contemporary theater director Kazuyoshi Kushida on the “Heisei Nakamura-za” project. The productions of this series of new-style Kabuki performed in specially constructed temporary theater facilities have become well established now and expanded into overseas performance in New York and other locations. In this age when it is normal to perform in existing theaters, it certainly seems very contemporary and cool to mount traditional theater performances in a temporary facility.

- At the time the Heisei Nakamura-za project started (2000), Kanzaburo had already begun his “Cocoon Kabuki” series at contemporary theater hall. Although he had broken out of the Kabuki-za with that new series, he still felt the constraints of working in an existing theater facility. He said that he wanted to do Kabuki someplace that didn’t have those constraints and to recreate the atmosphere of the small [often makeshift] Kabuki theaters of the Edo Period. He wanted to perform in his own theater facility, even if it was no more than a tent. At first he apparently imagined the venue would be something like a circus tent, but when he came to see the actual temporary theater facility when it was almost finished, he was surprised to see what an impressive facility it was.

- That first oval-shaped tent facility truly was well constructed. How was that facility actually made?

-

That temporary theater was not an attempt to faithfully reproduce the Nakamura-za theater as it was in the Edo Period. I designed the exterior and the interior to be what you might describe as a showpiece of the Heisei Nakamura-za project based on my own interpretations of

nishiki-e

(ukiyo-e) prints of the Nakamura-za from the Edo Period. The main structure of the building is a tent, but the front entrance was made as a fully decorated facade and all the interior parts were done as

odogu

set decoration. In that sense you could say that the entire Heisei Nakamura-za theater was one big set in the

odogu

style.

I designed the temporary theater’s interior with the traditional sajikiseki (tatami seating areas) and rakanseki seating just like the Edo Period Kabuki theaters. The rakanseki are exclusive seats positioned over the stage side of the inside of the main curtain, so when the play ends and the curtains are drawn they still have a view of the stage. I also designed the seating throughout to be tight in terms of space in order to create the feeling of a “packed audience.” I also included daijinseki , which are equivalent to the “royal box” in an opera theater and positioned directly in front of the stage in a way that enables the traditional device of having the actors interact with its occupants during the play. - All that was certainly sufficient to give the atmosphere of the small Kabuki theaters of the Edo Period.

- In short, you have to have the three basic elements of the audience the actors and the building come together in order to create that kind of atmosphere. It is sort of like a traveling amusement park concept: if you have these basic elements, you can create a real Kabuki atmosphere anywhere, and that is the purpose of the Heisei Nakamura-za theater facility.

- Are there any special stage devices built into it?

-

It doesn’t have the rotating stage that is often used in Kabuki, but it does of course have the

naraku

(trap under-stage), the

hanamichi

(stage entrance runway through the audience seating area) and

suppon

(trap in the

hanamichi

with elevation mechanism for rising entrances). There is also the passageway under the

hanamichi

that enables actors who have exited over the hanamichi to return to the stage area unseen. In fact the stage surface is a full 2.3 meters above the ground and the audience area is also raised to allow for a passage under the

hanamichi

. That is why you climb a set of stairs to the audience area when entering the theater.

And there is absolutely no stage wing area. That’s why the set sections that are not in use are just standing outside in the open, and the set changes are made during recess time between acts. So, if you go around to the side of the theater you can see part of the backstage and the set exposed, but we decided that it was OK. And we used exactly the same construction for it when we took the production to New York. - The 2004 performances in New York are still fresh in our memories. Was the entire set shipped to New York from Japan?

- The parts to construct the entire temporary theater were shipped from Japan. It took about a month by sea freight and filled about 30 shipping containers. And there were also some parts that couldn’t fit in the containers. But when the temporary theater was completed, it drew a lot of attention in New York and was written up in the New York Times , in the theater section as well as the home section.

- This year another Heisei Nakamura-za has been set up in the square behind the main hall of the Senso-ji temple in Tokyo’s Asakusa district for two months of performances in October and November. I have heard that it is a completely new facility this time. How is it different?

- Including the New York performances, this is the sixth time that we have built a temporary theater for the Heisei Nakamura-za series, and although it may not look much different from the outside, we have made changes in the design to accommodate the fact that we have only three weeks to put it up instead of a month. Changes were made construction process mainly to improve efficiency. For example, sections that were bolted together with ten bolts in the former design were re-designed to get the same strength with just five bolts.

- Where there any stage art plans that were made possible specifically because it is a temporary structure?

- The stage art plans have been done by director Kazuyoshi Kushida, and in plays like Kagamiyama he was able to use a large water trough on stage because under the stage is just dirt, so it didn’t matter if there was a lot of spillage. Kanzaburo’s policy has been that any stage art is OK with the actors as long as it helps realize Kushida’s concepts. Of course, this was also true with Kikugoro and Kikunosuke in NINAGAWA Twelfth Night as well, and in both cases the actors’ stance is that as long as there is a director, the stage art should all be left up to the director.

- Normally, in Kabuki there is no director, so the set designers work with the [lead] actors when building the set and we are told that it is a working relationship which requires the set designer to know all the preferences and peculiarities of each actor. If that working relationship is with the director rather than the actors in productions like Heisei Nakamura-za and Ninagawa’s NINAGAWA Twelfth Night , then it is really no different than contemporary theater for you, is it?

- That’s right. As stage designer, I am not being told anything directly by the actors. If there is something that comes up, the consultations are with the director. And when things come up it is not in the realm of design but about the acting or cues. But the actors and staff know very well that this way of creating the set and stage art is completely different from the methods of Kabuki. Personally, I have never once had that experience of working with the actors to design a set in the traditional Kabuki way. I have worked with Ennosuke Ichikawa and Koshiro Matsumoto IX but both of them were working as directors rather than actors in the traditional sense in those productions.

- Listening to these comments, I find myself being surprised by the flexibility of these Kabuki actors. Until now, I tended to have an image of Kabuki actors as artists who held more strictly to the traditions of Kabuki. Do you think this flexibility is representative of the recent trend in Kabuki as a whole?

- In the past, actors probably said that if there is no hanamichi you can’t do Kabuki. But in overseas performances there will be theaters where it is just not possible to put in a hanamichi . When Danjuro did Kanjincho at the Paris Opera House there was no hanamichi. It must feel very awkward for the actors not to be able to use the hanamichi for their entrances and exits, but when it wasn’t possible they accepted it and simply said, “Well, it can’t be helped.”

- In a play like Kanjincho where the hanamichi plays an important role in the climactic scene, you would think that the actors would say “No way!” about doing a production without it. The fact that they simply said, “Well, it can’t be helped,” must mean that there has been a big change in their ways of thinking. Now that your father Shunichiro Kanai as passed away, don’t you feel that the time has come for you to begin working on traditional Kabuki set design seriously? Do you intend to do that?

- I don’t have any worries in that area because the person who worked with my father for many years in our company’s Theater Dept. has taken over my father’s position as Kabuki set designer, but I do have the feeling that I would like to work on the sets of new Kabuki [newly written works for Kabuki] plays. But I imagine producers would fear that if they asked me to design a set they would end of having their theater turned inside out (laughs).

- Theater technical people like myself have been taught originally that there are no rules about how a theater should be used.

- That is the way I feel too. I believe that in one sense a theater is an expendable property. When we did Super Kabuki at the Shinbashi Enbujo theater, I had them take a saw and cut off the daijin-gakoi (used as rigging poles), which was a permanent fixture of the theater but got in the way of the lighting for our production. Since then, it has been replaced with a box that is detachable, but at the time no one [in the Kabuki world] would have considered tearing the poles like that. And there are many people who don’t approve of the theater being used in that way.

- Even though you have not always been watching Kabuki professionally, I know that you have seen a lot of the traditional Kabuki stages that has been over the centuries. Are there any aspects of traditional Kabuki style that you believe contemporary theater could learn from?

-

I don’t believe that there is any particular need for contemporary theater to learn from Kabuki. There are unique and imaginative designs in the Kabuki stage art tradition that might be interesting for contemporary theater to imitate, but in the end, every staging of a specific play has its own necessary design elements, necessary stage devices and necessary spaces.

Of course, I am not saying that there is nothing worth learning from Kabuki. Kabuki has its own unique stylizations and conventions and excellent theatrical know-how that has been handed down. If some contemporary theater director came to us and said they wanted to use a design from the traditional Kabuki set design dogucho collection at Kanai Scene Shop, I would gladly give them the materials and information they want. There are some people who might not be of the same opinion, but I believe that these traditional designs belong to us all, not any one person or company. And I don’t think that copying an isolated detail or two can qualify as an infringement of copyrights, and therefore there is no need to prohibit it. I would be pleased to have these things be used as a source of inspiration, but since the image rights do belong to our company, I would ask that they print the proper credits for their use. - You mentioned earlier that you would like to work on a variety of new works. By that do you mean that with regard to Kabuki as well you want to do works in a completely new style without referring to the old dogucho designs? Are there any real possibilities of that happening?

- [Director] Kushida has already begun doing that. His productions of Natsu Matsuri Naniwa Kagami and Sannin Kichisa in the Cocoon Kabuki series were done with completely new stage art. As is done with opera and other types of theater, I believe that it is all right to do Kabuki with completely new lighting, sets and costumes defined by the director’s stage plans. There are many good plays in the traditional Kabuki repertoire, and I believe that many new productions could be made with them.

- You believe that there are many plays that could be brought to life anew by employing the power of stage art?

-

Not just with regard to the Kabuki repertoire, but also from Japan’s

Shinpa

and

Shinkokugeki

, there are many good scripts and I don’t believe that they have to be done with old style stage art just because they are old plays.

I think there are many people who have a misunderstanding about what it means to uphold a tradition. Any efforts to uphold a tradition in the performing art are meaningless if you are not attracting an audience for it. Theater is not something that can be preserved like arts and crafts or tangible cultural assets. Trying to preserve theater only for your own sake is meaningless.

This is something that I often say at the company too: the funds to design and build stage art come from the audience. The audience are the ones who pay the salaries that enable us to work. If we don’t think seriously about what we are preserving the tradition for, we will end up simply becoming conservative. If you don’t understand this point, you will end up preserving the tradition in the wrong way. The job of upholding a tradition and the process of becoming conservative lie on two completely different vectors, I believe. - In other words, you believe that it is meaningless if it only ends up as nostalgia. And if people come to see Heisei Nakamura-za simply because they think they will see something new, that will also lead to nothing. You should at least show that Kabuki is still evolving. Is that it?

- The actors are changing and so are the directors, so I believe that it is an obvious truth that the theaters and the stage art have to change too.

Yuichiro Kanai

Meet set creator Yuichiro Kanai, 4th-generation president of a Kabuki set production company and set designer for contemporary theater and new Kabuki

Yuichiro Kanai

Born in Tokyo in 1960, Yuichiro Kanai graduated from the Department of Architecture, Faculty of Science and Technology of the Tokyo University of Science. Became the president of Kanai Scene Shop Co., Ltd. after the passing of his father, Shunichiro Kanai, in 2006. Awards include the Japan Theatre Arts Association Grand Prix (2001), the Outstanding Staff Award of the Yomiuri Theater Awards of 2004 for Yume no Nakazo Senbonzakura and the Heisei Nakamura-za production of Kagamiyama Gonichi no Iwafuji and the same Outstanding Staff Award in 2006 for the stage art for NINAGAWA Twelfth Night . In 2008 Kanai won the Ito Kisaku Award for stage art for Tsukigami.

Kanai Scene Shop Co., Ltd

http://www.kanainet.co.jp/

Interviewer: Toshiya Kusaka, President, Art Space Factory

SIS company production

Mabuta no Haha

May–June, 2008 at the Setagaya Public Theatre

Photo: Yuichiro Kanai / © SIS company

NINAGAWA Twelfth Night

Written by W. Shakespeare

Directed by Yukio Ninagawa

Photo: Yuichiro Kanai

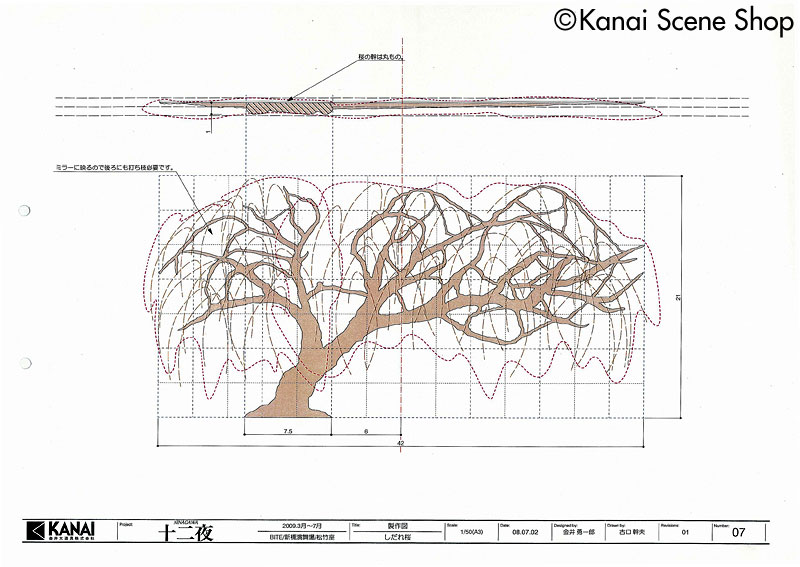

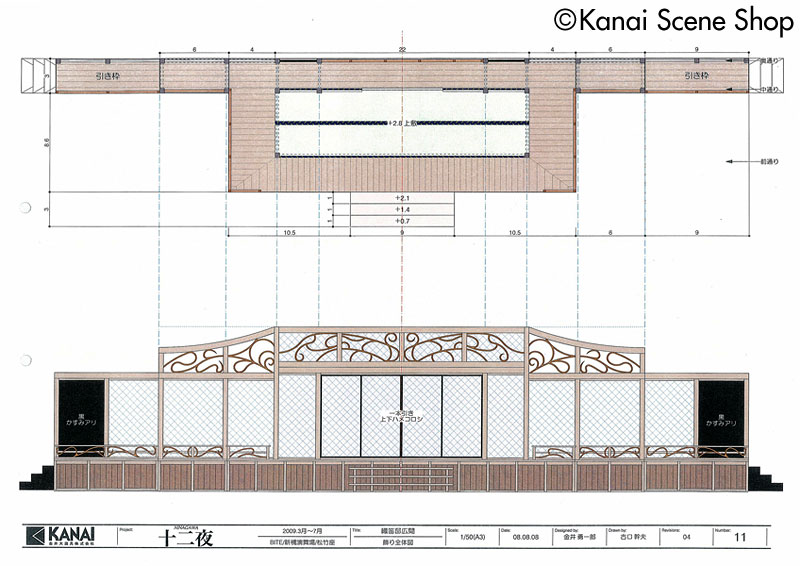

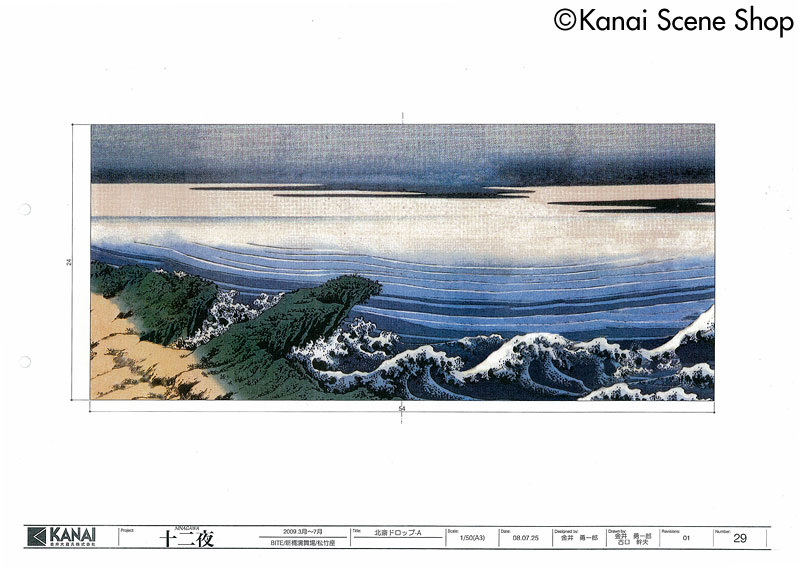

Technical drawings of the 2009 production of NINAGAWA Twelfth Night

(Written by W. Shakespeare / Directed by Yukio Ninagawa). It will be performed in London, Tokyo and Osaka in 2009.

© Kanai Scene Shop

Heisei Nakamura-za (Osaka, 2002)

Photo: Yuichiro Kanai / © Shochiku

Heisei Nakamura-za (New York, 2004)

Photo: Yuichiro Kanai / © Shochiku