-

As I understand it, you have three faces. First of all, you have been a member since 2006 of the performance artist group “dumb type” that created a sensation on Japan’s art scene in the 90s. Second—and this is something that I think many people don’t know—you were the director of the Tokyo International Lesbian and Gay Film Festival until several years ago. Thirdly, you have a presence in the Japanese contemporary dance, creating highly innovative performance art works in collaboration with a variety of artists from different fields. In this interview we would like you to talk about the first and the third topics.

Before you became a member of dumb type, you were involved in a number of unique activities from the 1980s. Could you tell us how you came to use your body as an expressive medium for art? -

When I trace things back to my childhood, I played the lead part in our kindergarten play

Kobutori Jiisan

and in elementary school I was the conductor for the class concert. Then in middle school I was involved in the theater club and in high school I won the top prize in the costume parade contest at our sports festival dressed as Alice of

Alice in Wonderland

(laughs). In short I was a child who always stood out and enjoyed being in the limelight.

In my senior year of high school I spent a year in the US as an exchange student. There I ended up doing a musical with the kids there, and before I knew it I had fallen in love with theater and musicals.

At university I majored in Spanish and was in a club that did Spanish-language plays and performed in Spanish as an actor in a number of plays including Garcia Lorca’s Yerma . - I had known that you were good at languages, but I didn’t know that you had majored in a foreign language.

-

When I was in university, one of my part-time jobs was to do listings and write recommendations for performing arts for the English monthly magazine called Tokyo Journal. I continued that job for about ten years and it was the time in the 1980s when a lot of foreign artists and companies started coming to Japan. There were such a rich variety of things going on. I was able to combine work and my own interests and see a lot of performances in theater and dance, regardless of genre. Among the many performances I saw during those years, one that left the deepest impression on me was Pina Bausch’s

Rite of Spring

and

Café Müller

in 1986.

As for my own activities, I continued to do Spanish plays at the university, but that wasn’t enough for me. In my junior year I took part in a movement theater workshop. There I learned a type of movement theater called “mime” in French based on pantomime from a theater company leader named Mamoru Nishimori who had studied and worked for the company Théâtre de La Mandragore in Paris. It was so interesting that I decided to enter the company’s training course, and after two years I was able to perform in the company productions. The performances that company did were based more on physical movements rather than words or scripts. It was an abstract kind of expression that sought new possibilities in the techniques of pantomime as part of the analysis of use of the body in theater. I continued working in that company even after I graduated from university.

Back in those days there was a performance art festival called the Hinoemata Performance Festival in the remote village of Hinoemata at the entrance to the Oze natural park area of Fukushima Prefecture, and I was given a chance to perform as a dancer in the work of Roku Hasegawa, and danced with Roku herself and Kota Yamazaki [contemporary dancer] with the experimental music of Kazue Mizushima [the “Stringraphy” artist/composerwho currently known for her works with silk threads crisscross a large space, using the whole things as an musical intrument] and . The Festival in those days gathered a lot of avant-garde artists working in ways that transcended the conventional boundaries between artistic genres. They were people incuding Shigeyuki Toshima of Molecular Theatre, the experimental film artist Takahiko Iimura and the performer Goji Hamada as well as many butoh artists. You could say that I got an interesting initiation into the world of performing arts through that festival.

During that same period, I was attending the workshops of the contemporary dance Saburo Teshigawara and Mika Kurosawa. I went to the classeds of Kurosawa for about half a year at her Tsunashima Studio and even performed in her work series Eve and/or eve . - When did you begin doing your own works, and what kind of works were they?

-

The first was a work based on Tennessee William’s

Talk to Me Like the Rain and Let Me Listen

I did at the Nakano Terpsichore theater in June of 1988. I wrote the script and directed and performed in it, and the music was by Mizushima again. It wasn’t an attempt at realism theater but a freely arranged, uniquely conceived work of performance. I deconstructed and rearranged the script, used abstract movements and a unique vocalization method. I think that this became the base of what I still pursue today.

Out of a desire to study Spanish theater, I went to Barcelona on a Spanish government scholarship for a year beginning in September of 1988. But because I could not catch up with the graduate school level of the courses I took there, I spent most of my time going to theater performances instead.

Besides Spanish plays I also went to see performances of La Fura Dels Baus and other avant-garde stuff including the Russian experimental theater. I also saw the Belgian company Rosas’ production Ottone, Ottone . I also took part in experimental theater company workshops, and since Barcelona was open to for new arts, I really loved it and enjoyed it. - It seems that in order to really understand you, we have to understand your time and experiences in Spain. It seem like that year laid important groundwork that you would build on later, didn’t it?

- Still, my career in the performance arts had not yet begun at that time (laughs). Soon after returning to Japan, the butoh artist Gan Tokuda asked me if I wanted to join in the New Year’s eve performance marathon. My contribution was a 4-person performance which I created with Atsuko Yoshifuku, who had been dancing with Mika Kurosawa’s company. Although the piuece has some spoken texts, it was not theater and it was not dance. I guess you would have to call it “performance”. Anyway, it was interesting enough that I decided to form a company with Yoshifuku, which we named ATA DANCE. At that time, the Omotesando street in Tokyo was a closed to traffic as a pedestrian walk on Sunday’s and a lot of different groups were doing live street performance there, and we started performing street dance and performance regularly there too. In the Pina Bausch work 1980 that I saw in Spain, the dancers formed a line and performed elegant dance movements while parading forward in line. I copied that form and we danced in line along the Omotesando street which was, and still is today, Tokyo’s fashion center. At the time I felt that we were dancing very fashionably, but I don’t know what the passers-by who saw us were thinking (laughs).

- I am told that you continued that type of street performance at Omotesando for about three years.

-

Yes. Then we began to think that it was time we had tried something in a theater. The first work that resulted from that idea was

mata-R

, which we performed at Yokohama ST Spot in 1991. That year would be an important turning point in my career. It happened that that was the year when William Forsythe first came to Japan, and I went to see his production

Impressing the Czar

. Then I went to watch the workshop he gave at the Geothe Institute in Tokyo and I was completely enchanted by the things he said and the body movements of his company’s dancers. As I watched the magical movements of his dancers as he spoke the words “points connect to form line, and lines connect to form planes,” I couldn’t help talking to him saying like, “You have just shown me what was exactly in my head. Thank you.” Then he said, “Sure, go ahead. Steal.” The resulting change in my consciousness from that experience is what gave birth to

mata-R

, which became my first piece I choreographed, directed and also performed in.

With the momentum from that work, I decided to enter the 1st Tokyo platform of the Bagnolet choreography competition, but the only response I got from the judges was that it was an “ambitious” work (laughs). - When you applied to the Bagnolet Competition, was it with the intention of making yourself a career as a choreographer?

- I am not really the type to make that kind of decisions. I had always just continued doing what felt interesting to me. And, that is how I continued ATADANCE until I finally ran into a wall. We had reached the point where we were receiving grants as a dance company, but that meant on the other hand that we had to produce “dance works.” When I began to realize that I had to fit myself into that framework, I hit a wall. I began to feel suffocated because I felt I was just running after something alien rather than discovering what was inside me. That is why I decided to disband ATA DANCE in 1995.

- That is when you joined dumb type, is it?

-

Yes. Of course, I had seen dumb type’s first Tokyo performances of

Pleasure Life

and their 1989 work

pH

. And, I had already known members Teiji Furuhashi, who died of AIDS, and Noriko Sunayama, who came to dumb type after dancing with Mika Kurosawa & Dancers. But, I had never worked or performed with the company before. Shortly after Teiji died in October of 1995 in Kyoto, I worked as a performer in the production of Michael Nyman’s opera

The Tempest

that was directed by Robert Lepage. At that time, dumb type was planning a collaboration with the Danish performance group HOTEL PRO FORMA in a large-scale performance work titled

MONKEY BUSINESS CLASS–SARU HODO NI

. It just happened that the Danish director came to see the Kobe performance of

The Tempest

and afterward invited me to come and work with them as a performer.

That work was my first opportunity to work with dumb type, and after that I asked if I could join in OR at the end of 1996. For the project we stayed for one month in a small town called Maubeuge in northern France to create and premiere the piece in March 1997. At the time, there were rumors that dumb type would break up now that Teiji had passed away, and we in the group were also asking ourselves what we could do as an artist group without Teiji. Somehow, there was a feeling among us that we would continue working together nonetheless. - The group dumb type was formed in 1984 and from the late 80s into the first half of the 1990s it had already achieved a unique position in Japan’s art scene. It toured abroad frequently to create and perform works. Not only did they approach the central theme of technology and the human body in mixed-media art with a critical and ironic approach, but they also dealt with political and social themes such as AIDS, sexuality and nationality in their works such as S/N . What’s more, dumb type was a new type of artist group that never adopted the kind of hierarchy that exists in other Japanese theater companies, but created works in a style by which artists in the different fields of film/video, music, architecture and dance jointly contributed their individual ideas and techniques to the whole. Still, the leadership of Furuhashi was substantial. After Furuhashi’s death, Ryoji Ikeda joined dumb type for the first time in charge of music, and the first work that the group presented with him was OR , a work on the theme of “Life or Death.” After that, the works Memorandum and Voyage followed.

- For me, Memorandum was the piece I enjoyed the most the creative process of . As a performer I was on stage the longest time, and there was a good sense of achievement for me in terms of the creative processes.

- The concept behind Memorandum was an exploration of memory. There was a scene in which a man writes down fragments of memories on a notepad which we could simultaneously read on the big screen. Then we were flooded with endless images of memory to very loud music. Watching it, I got a feeling that things outside the body and things inside were being linked together. In contrast, the group’s next work, Voyage , which featured a metallic floor with the reflections of the dancers, clearly brought a sense of distance to the forefront.

- Voyage was created while staying in the French town of Toulouse. It does indeed gives a sense of distance, and it is a very static work. One French critic said to me he saw an intention to terminate the [role of the] body in the performing arts, and that “if you try to terminate the body I would have liked to see you do it with use the body.” Since then, we continue working on the piece as we tour, trying to make it a little better every time we perform it.

- What kind of activities are you thinking about for dumb type for the future?

- To be honest, we don’t know very clearly. We are still touring with Voyage , but we don’t know what may come next. Everybody has his/her own things as well, and there are times when certain members team up to work together. I also presented my own work Sekai no Chushin ( The Center of the World ) at the Park Tower Next Dance Festival in 2000, and I did Night Colour the following year.

- Sekai no Chushin is the work largest in scale that you have done to date . Although I could see some influence from dumb type tt had a unique flavor of your own… It was a work in which you dealt with the theme of your sexuality, bringing in characters like a gay transvestite (drag queen) walking around dragginging the train of a gaudy dress he wore and a gay porn film actor.

- The title, Sekai no Chushin ( The Center of the World ), is also gaudy, isn’t it? (laughs) The Next Dance Festival offered me a great opportunity to do a work of my own.

- This is a festival that aims to discover young talents in contemporary dance. If it were in New York, for instance, there might have been numerous works questioning such issues as sexuality and gender, but not so in Japan yet. Your work was unique in the way that it dealt so directly with these questions, but without becoming too dogmatic. It had a very pop and camp taste instea d, which I thought was very unique in Japan. I am not so sure, however, if others in the audience agreed with me.

- There were a lot of women in the audience who were supportive of my work, it was mostly men who couldn’t understand why I had to address the subject of my own sexuality on stage. in my work, talking about myself is essential. My recent works are much more autobiographical and personal than those I did for ATADANCE.

- The solo performance Night Colour that you did after Sekai no Chushin was a very beautiful work where you kept an objective stance over your own dance while the movements were very much of your character.

- Night Colour is a work that I first created at Grand Theater Groningen in Holland back in March 2001. In dumb type’s Memorandum I have a solo dance scene in which I patchworked random images and movements. I used the same method in Night Colour too. I combined my movements, a minimalistic lighting and music, and some video images in a white square space. Later, I asked Takayuki Fujimo, the lighting designer of dumb type to redesign the lighting using the new LED lights I added some improvements and performed it again. In 2003 I shoed the piece at the Asian Performing Arts Festival in India.

- After Night Colour you did the collaborative work D.D.D. with Fuyuki Yamakawa in 2004. I personally believe this to be one of the most outstanding works to be produced in recent years. It was a work where you seemed to be involved in a one-man battle in the limited space on top of a 120 cm x 120 cm table while Yamakawa put out the sound and light of his own heart beat and breathing on stageFirst of all, what doesthe title D.D.D. stand for?

- It stands for “Don’t Do Drug!” (Laugh). Well, seriously, it is the sound of the heart. It should be pronounced as “deh, deh, deh” as in French or German. I thought that’s how my heart sounded. In the show, the actual beat of Yamakawa’s heart is amplified.

- It is shocking when you come out on stage wearing a full-head mask like in a commercial wrestling match. And like a boxing match, the show has a total of seven rounds, unfolding different scenes of a self-battle on top of that small table. What was the starting point for this work?

- In the beginning, I wanted to do a kind of performance in which i would slam my body against a floor or a wall. I was planning to premiere the work at “Super Deluxe”, a club in Roppongi, Tokyo, and coincidentally Yamawakawa was doing a live there, so I went to see it. It was a very powerful show, combining the sound of his own heart, the light bulbswhich flashed in sync with his heart beat, and his own hoomei throat-singing. I was so impressed that I immediately went to him afterwardsthe show and asked him if he wanted to work with me. Yamakawa says he feels his body is the only medium with which he could make the kind of art he could call his own. His actions are always direct and strong.

- It doesn’t take a dancer or a musician to just do a body slam, but to make it an artistic expression, I think, is not that easy at all. D.D.D. was a wonderful performance where you two artists united to become one strength. You have toured overseas with this piece and won high acclaim. What do you think is the reason for that acclaim?

- It is difficult to say what is good about your own work, but I see D.D.D. as a work that deals with primal desires in a direct way while bringing in pop elements like heavy metal music and Japanese pro-wrestling. That may be why it’s been popular. Yamakawa is a powerful performer and in that sense it is also a battle between the two of us. You could say that while he battles from inside the body I am fighting from the outside.

-

You certainly seem to be svery good at finding good people to collaborate. By nature, artistic collaborations are very difficult, and they are often predictable and boring. Putting two interesting talents together doesn’t necessarily bring an interesting result. On the contrary, it can often work negatively.

In your case, however, works like D.D.D. and Di Que No Ves (Say You Don’t See) (2003) with the artist Atsuhiro Ito who uses florescent light tubes, are excellent examples of what a collaboration should be like. Through these collaborations you have succeeded in finding new strength which you might not have found otherwise. - When I do a collaboration for my own works, I put a great amount of thought into how we each bring our own stuff, how we cut into each other, and combine them in order tobring a new dynamism into the work. When we did Di Que No Ves I honestly didn7t know what to do in front of Ito’s violently bright fluorescent light and sound, all I could do was to try spinning and spinning because I imagined the effect of the strongly augmented fluorescent light and electric noise would stimulat my sensory system to the limit, and eventually numb my senses and as I succumbed to the dizziness of the spinning I would fall to the ground.

- What kinds of works will you do now?

-

I want to work with more people. And I want to use texts. I would like to work with texts and visual images and the body on the same level, I think there are a lot of possibilities.

Right now I am working on a new work titled “ true / Honto no koto ” for performance at the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media. As director, Takayuki Fujimoto has brought in the contemporary dance artist Tsuyoshi Shirai, and he invited me in too, and I am looking forward to seeing howwe can work together.

I have also done a collaboration on a work called “Tablemind” with the sound artist Daito Manabe, who is also on this project “true.” I would like to work some more on piece.

After this, I will be working with the performance company called Yubiwa Hotel in their new project Exchange which will premiere in October this year. With Yung Myong Fee, an strong female dancer, and Yubiwa’s artistic director Shirotama Hitsujiya, I feel this is going to be something very different from anything I have ever done before, and therefore, challenging. I am very excited.

In terms of the direction of works for the future, I want to use a lot of different methods and narrative styles without concern for genre or methodologies. Of course, in the end you have to be selective of what you choose to, but I would like to be open to different media, styles, and methods, and find an expression that is unique to the chose medium. That is true for both collaborations and solo works. It may be the easiest to call what I do “performance” but I believe that in the end, something interesting can only be born where the method and the content are so one that they cannot be separated. Say, you come up with a new language of saying something, and that something can only be said in that language. That’s something I would like to explore. For me, the core is using the body for expression, but I want to pioneer forms of expression that transcend conventional sense of values. - In one sense, it is strange to have techniques that are limited to one genre and to be limited by what you can express within that framework. And I think that we have now reached the point whereartists today are expected to take on the challenge of discovering new possibilities in the realm of expression.

- Yes. That is what is interesting about “contemporary” arts. There may be a question of whether or not it is contemporary in that sense, but I don’t see any need to create divisions such as “contemporary dance” or “contemporary theater.” In the visual arts as well, the boundaries are breaking down and architecture and art are now being fused into one. I believe what contemporary means is not that if you are a dancer you concentrate only on dancing but, in the end, it involves everything we do in this limited time we live in this world. In that sense, if art itself has embraced all the arts and become one genre already, we may as well be now at the stage where we questioned that genre too.

Takao Kawaguchi

Exposing his own body as a platform for art -- A look at the mixed-media performance art of Takao Kawaguchi

Takao Kawaguchi

Born in Saga Prefecture in 1962, Kawaguchi is a member of the performer/artist group “dumb type.” After being active in a Spanish-language theater circle in college, he studied a type of movement theater called “mime” based on pantomime while also participating in a number of projects ranging from experimental theater to dance and performance art. In June of 1988 he mounted his own first production, an experimental performance based on Tennessee William’s Talk to Me Like the Rain and Let Me Listen at Nakano Terpsichore, Tokyo. From September of the same year he went to study at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona on a Spanish government scholarship. Returning to Japan, he joined in the forming of the dance company ATA DANCE with Atsuko Yoshifuku in 1990 and performed with it until its dissolution in 1995. And then, from 1996 he joined the artist group dumb type and took part in creation and the tours of OR , Memorandum and Voyage . The company is still touring with some of the pieces today. From 2000, he has been performing actively with artists, musicians and performers of various genres as well as doing solo works including Night Colour (2001), Di Que No Ves (Say You Don’t See) (2003), D.D.D. (2004), and Tablemind (2006). D.D.D. is a collaboration with the Khoomei (throat singing) artist Fuyuki Yamakawa, who creates works on the theme of technology and the body. Since the piece was premiered in Tokyo in 2004, it has been performed at the Queer Zagreb Festival in Zagreb, Croatia in Sept. 2005, the Venice Biennale in June 2006, the MODAFE 2007 festival in Seoul, S. Korea in June 2007 and at Esplanade in Singapore in July 2007.

Interviewer: Tatsuro Ishii; interviewed on Aug. 10, 2007 at the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media

* Voyage (2002, premiered in France)

is a work created in the aftermath of the 9/11 terror attacks in the US in 2001. Contrary to the group’s usual working process, the group was divided into small units to work separately on different scenes and motif, all of which we later found out somehow shared a sense of ‘journey ( voyage )’. The stage floor was covered with metal and the reflections of the video images in it helped to create the mood which kept changing drastically from one scene to another. The dancers appeared to be suspended weightless in the middle of the space without gravity.

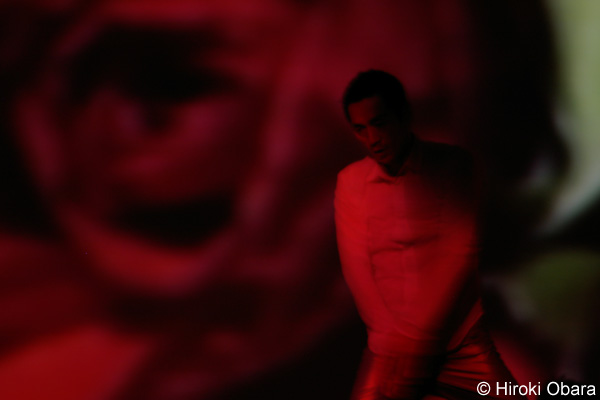

Takao Kawaguchi

Night Colour

Photo: Hiroki Obara

Takao Kawaguchi

Di Que No Ves

(Say You Don’t See)

Photo: Daiki Obara

© Takao Kawaguchi

Takao Kawaguchi

D.D.D.

Photo: Daiki Obara

© Takao Kawaguchi

YCAM Artist in Residence Program

true

Tsuyoshi Shirai, Takao Kawaguchi, Takayuki Fujimoto

Choreography, performance: Tsuyoshi Shirai (Baneto/AbsT), Takao Kawaguchi (dumb type)

Lighting, director: Takayuki Fujimoto (Refined Colors/dumb Type)

Sep. 1, 2007 / Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media

Dec. 8-9, 2007 / 21st century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa

Dec. 14-16, 2007 / Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse No. 1

Yubiwa Hotel

Exchange

Director: Shirotama Hitsujiya

Cast: Yung Myong Fee, Takao Kawaguchi, Shirotama Hitsujiya

Oct. 4-7 / Theatre Iwato (Shinjuku, Tokyo)

Oct. 13-14 / Kyoto University of Art and Design A studio

Oct. 19-20 / Concarino (Sapporo)

Related Tags