- All Japanese are familiar with the chanting of Buddhist scripture, but the term “shomyo” is not commonly known. What is the difference between shomyo and the more familiar forms of scripture chanting?

- Shomyo is Buddhist scripture that is set to melodic phrasing and chanted at Buddhist ceremonies in temples by a chorus of male monks or priests. You might call it a form of Buddhist canticle which admires Buddha and teachings of Buddhism. It was born in India with the development of Buddhism and was subsequently transmitted to China and the Korean Peninsula before coming to Japan. Buddhism was first brought to Japan in the 6th century, but historical records trace the first appearance of shomyo in Japan to a ceremony for the consecration of the Great Buddha at Todaiji temple in 752 AD. It is written in this record that 10000 priests and monks from all over the nation gather for this ceremony and 420 of them chanted scripture together in the shomyo style.

- Can you tell us more about the history of shomyo?

-

The origins of the word shomyo can be traced back to the name of an ancient Indian (Sanskrit) word for “sabda-vidya” as “the study of language.” In China and Korea, a term that we call

bonbai

in the Japanese reading, and that was mixed with the Sanskrit some time in our early Kamakura period (13th century) resulting in the term shomyo.

Early in the 9th century Kobo Daishi (Kukai) brought “Shingon Shomyo” to Japan from China, and in the mid-9th century Jikaku Daishi (Ennin) introduced “Tendai Shomyo,” and these traditions developed separately within the different Buddhist sects over the centuries. The most important period of shomyo development was from the Heian Period (9th to 12th centuries) into the Kamakura Period (13th century). It was during this era that the musicology of shomyo, the form of musical notation and the collections of the musical scores were compiled and the methods for teaching them were set down. In 1472 a collection of shomyo scores “Collection of Shomyo 1472 version” was printed at the temple complex of Koyasan, and this is said to be the oldest existing printed musical score in the world. The printing of this collection led to the spread of shomyo throughout the country. And, it is interesting to note that the oldest known printing of scores of Gregorian chant dates to 1473. So, we were just a year earlier [laughs]. Talk about music history tends to bring to mind Western classical music, but as this proves, Japan has also made important contributions to the world history of music. - What kinds of music are there in the shomyo tradition?

-

There are three kinds of shomyo chants that have been handed down to us today. One is the Sanskrit chants from India, the second is the Chinese chants that composed independently in China later on, and the third is the Japanese-language chants composed in Japan. What we use in Buddhist ceremonies in Japan today is a well-arranged mix of the three.

The “Shichi Bongo no San” (*1) chant that is used often today in Buddhist ceremonies dates back to 7th century India. The oldest of the shomyo born in Japan is the “Shari San Dan” (*2) composed by Ennin in 860. Having seen and heard many ancient Korean (Silla Kingdom period) chants during his studies at a Korean temple in China, Ennin probably decided that in order to establish Buddhism in Japan and have it spread among the people, it would be necessary to have chants in Japanese that the people could understand.

If you were to ask how many chants there are in the shomyo repertoire, I would be hard put to answer. And it is hard to say what constitutes one chant, because they are not chanted separately. They exist as components that are put together in different ways for the different Buddhist ceremonies. Also, there are many cases where the same piece of shomyo scripture will be chanted with a completely different melody and rhythm by the different sects. - What are the differences between the shomyo of the two main sects, Shingon and Tendai?

- If you listen to them, the difference is clear. Generally speaking, Shingon shomyo has a more masculine and dynamic sound, while Tendai shomyo is said to be more feminine and elegant. The major musical difference between the two is a decorative voice called “yuri,” which is like swinging sounds or tremolo. In the Shingon sect, the “yuri” we use has a rougher sound and we chant each line with breaks in between, and each word has its own intonation. In the Tendai style, each “yuri” is drawn out slowly, and it uses long breaths and therefore has a meditative aspect. Also, the way the scores are written is completely different, so we can’t read each other’s scores. And, there are some shomyo chants that only exist in the Shingon repertoire and vice versa. At the time of the consecration of the Great Buddha at Todaiji temple during the Heian period, the “Shika Hoyo” (4-part recitation consisting of a “Bai” a “Sange” a “Bonnon” and a “Shakujo”) was probably chanted together all the priests of all the sects, but after that, shomyo underwent different courses of development in each sect.

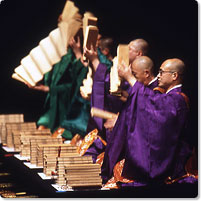

- It is certainly an impressive thing to hear the reverberation of the voices of a large group of priests chanting shomyo together in a temple. Is it correct to think of shomyo as basically a form of choral music?

-

Yes, it is. There are some cases where a senior priest will recite a solo chant like a “Bai” at the beginning of a ceremony, but fundamentally shomyo is chanted in chorus. There is a head priest who leads the chant and he will begin the opening phrase and then all the other priests join in the chant.

In the chants created in India and China, it is simply a matter of stretching out the vowels and adding tonal variety there, but there is by no means any type of musical development that evokes emotional feelings like melancholy or joy. On the other hand, there are also narrative “ Koshiki ” shomyo chants like the Shiza Koshiki (*3) , which is sad in tone because it tells of the death of the Buddha, so we change the pitch (1st, 2nd and 3rd levels) to achieve a more emotional effect. But one of the rules of early Japanese music is that you don’t give blatant expression of human emotions, and it seems that the common practice is to giving musical expression to the different scenes by setting a particular tonal range for each scene in the narrative. That is exactly what you find in the heikyoku recitations of the Tales of the Heike narratives (originating from the 13th century). It probably wasn’t until the Edo period (17th to 19th centuries) that strong expressions of human emotion were introduced. - What are the shomyo scores like?

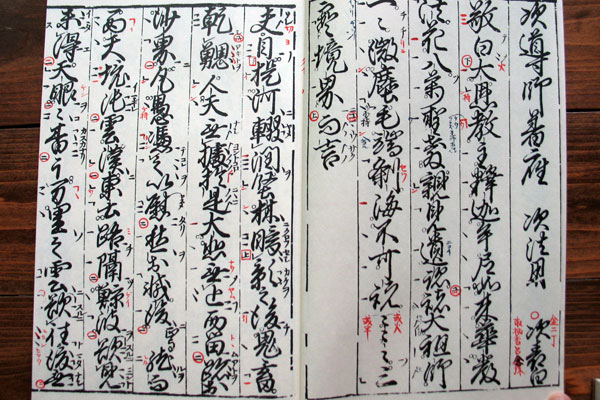

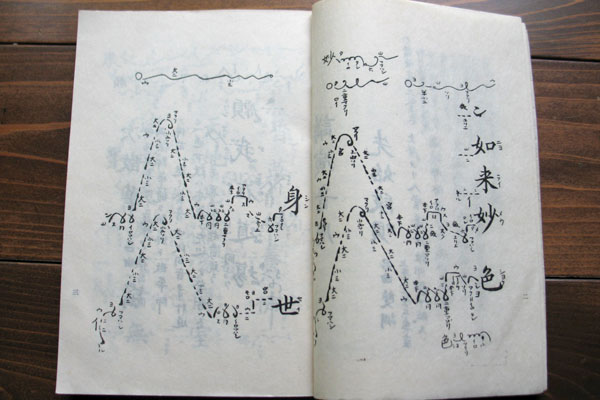

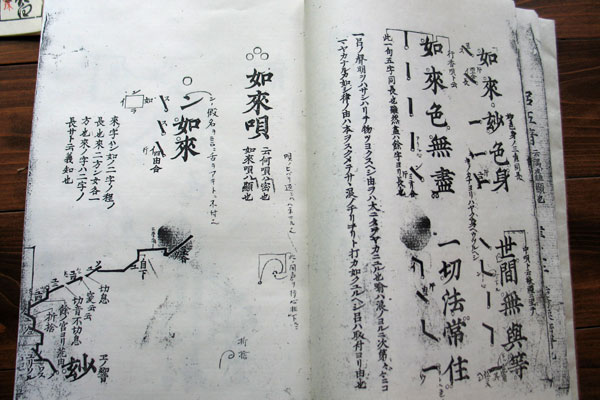

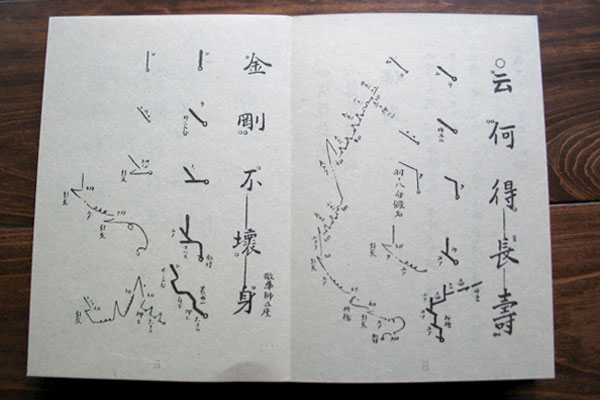

-

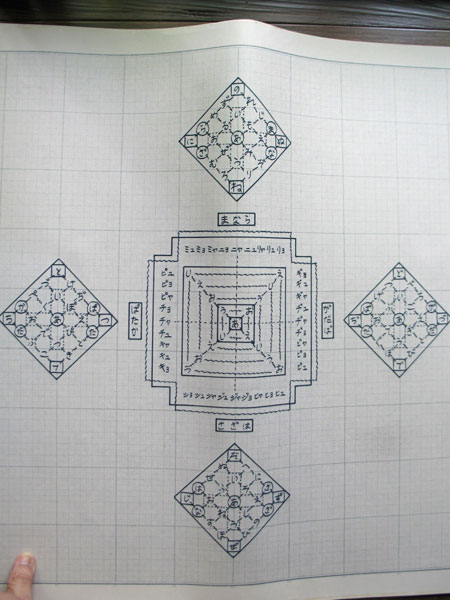

The shomyo score is called

hakase

and it has the chant text and notations of the melodic patterns. The form of the sound, in other words the form of the melodic patterns, is learned as one unit, and each chant is made up of a certain combination of melodic patterns. Also, lines are used on the score to represent the cadence or intonation of the voice and the length of the notes in a visually readable system.

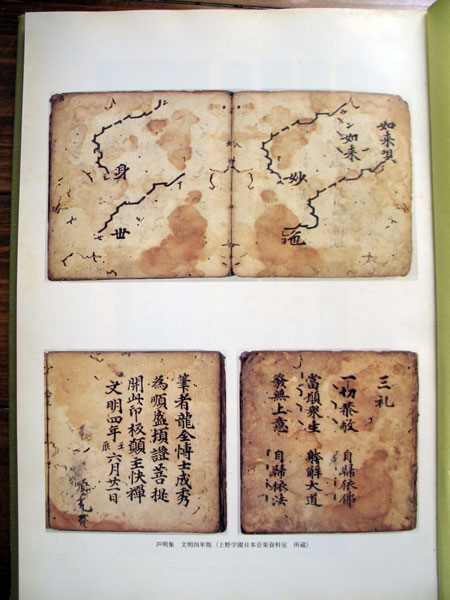

After the publication of the first printed scores in 1472 in Koyasan, an instruction book explaining how to interpret the scores was edited in 1496. This was basically the same as the hakase scores used today. However, currently when we teach the young people we use the practice scores which have been further visualized from the real hakase to make them easier to understand. A shomyo score from around the 10th century that was found at Dunhuang, China, and is kept in the British National Library has been called the world’s oldest, but just recently the oldest record is updated when so-called “Neuma” scores written in line form from around the 8th century were found. These scores had supposedly been brought back to Japan by monks who had been sent to study in Korean Silla Kingdom. - Shomyo is usually learned from a master priest by oral transmission, but is choral practice done as well?

- There are shomyo classes for the young novice priests in every academy of all sects’ main temple, but basically they learn the choral part naturally by ear in the course of their daily morning routines and the religious ceremonies they participate in. The important thing is to be listening to the mutual resonance. Rather than practicing tonal harmony specifically, I believe that they all learn it naturally in the course of their daily lives in the temple. Of course, the more difficult chants are learned by going to the master priest to be taught, but the more basic chants are learned naturally by hearing them over and over. And what is fascinating is that in the course of that learning distinctly different “voices” have developed at the different temples, like the Koyasan voice and the Hiezan voice and our own Hasedera voice. In the hundreds of years of priests living communal lives at the respective “mountain” temples where novice priests are trained and chanting the scriptures together every morning has led to the development of distinctly different shomyo unique to each temple. I believe that the unique quality of the acoustical environment of the place where the prayer chanting is done is closely related to the quality of shomyo that has developed.

- In Western classical music there is a conductor, but does anyone serve that role in shomyo?

-

No. In Western music there is a conductor who controls the rhythm and pitch virtually with each phrase of the music in very precise and exacting ways, but in shomyo we harmonize and synchronize by listening to each other, so there is nothing really unpleasing if the pitch or tone in not exactly perfect. So, what we are often told is to listen well to each other. The natural way to learn the tempo and rhythm is simply by lots of repeated chanting.

There is a set tempo for each chant, and Tendai shomyo use a tuning flute of anything to get exact pitch to start chanting. But in Shingon we don’t need to get exact pitch. And, even if it is the same chant, we will change to the tone of expression depending on whether it is for an invocational prayer service or a funeral, etc. Unlike Western classical music, shomyo has that kind of room for flexibility. - I have heard that the roots of much traditional Japanese music (hogaku) and classical arts are found in shomyo.

-

It is safe to say that most of the ancient Japanese vocal music and narrative forms, from the lute accompanied Heike Tales recitations (Heikyoku) and the melodic recitations of Noh plays (yokyoku) to the shamisen accompanied joruri narratives and

Naniwabushi

ballads, and even to

rakugo

traditional comedy skits, all grew out of the shomyo tradition. The late renowned researcher of ethnic music, Fumio Koizumi, says that Japanese shomyo we call

Koshiki

was probably the first example of a musical recitation style being applied to story telling. It is believed that the other forms like

Heikyoku, yokyoku

and

Naniwabushi

ballads all developed from there.

Another reason for believing the roots of these ancient arts are to be found in shomyo is that Buddhist temples functioned as the venues for festive occasions and ceremonies from ancient times into the feudal period. For example, the grand consecration ceremony for the Great Buddha of Todaiji temple was an occasion where many commemorative performances of different arts were given in honor of the Great Buddha. At the time it was certainly a grand event to boost the national prestige and emissaries were invited from the neighboring countries came to watch. You might compare it to an event in the manner of today’s Olympic Games opening ceremony. There were large-scale recitations of shomyo was performed. Also, there were acrobatic troupes and mask theater from China and various performances from other Asian countries like Vietnam and India. In short, the Great Buddha Hall in Todaiji became grand performance stage and festive space.

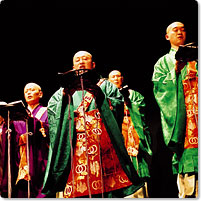

In Japan, Buddhist priests have traditionally performed only choral shomyo, but on the continent priests performed choral chanting, dance and instrumental music together. Still today in Korea and Tibet the priests perform music and dance. - When did you begin giving shomyo performances on stage in concert halls and theaters?

-

The first such performance was when the National Theater, Tokyo was opened in 1966. This was an epoch-making event through which shomyo was viewed as “music” for the first time.

However, at the time there were also those in the Buddhist holy community who complained it was unseemly for priest to be signing for audiences in a theater. They said it was a sacrilege against the Buddha. In answer to this, our teacher, the high priest Yuko Aoki said, “The Buddha’s presence is spread evenly throughout the universe, not only in the main halls of Buddhist temples but in the streets of our cities as well. Let us actively seek out any place where people will listen to shomyo with a receptive heart and mind”. Even past the age of 80, he continued to perform throughout Japan and also overseas. We were still in our 20s and for us, Yuko Aoki, who was our teacher and also a “Living National Treasure” designated by the Japanese government, was a great influence on us.

In 1973 the first overseas performance of shomyo was held in a tour titled “Japanese Tradition and Avant-garde Music” sponsored by the Japan Foundation (as one of the first independent projects when the Japan Foundation was founded in 1972). Yuko Aoki led our group and we toured the world for 43 days, beginning from Tehran, Iran, Europe, America to Canada. This tour resulted from a visit to Japan by Mr. Heinemann the director of a comparative musicology study institution in Berlin and Mr. Becker the head of the contemporary music department of the West German national broadcast network. When they asked if there wasn’t an older musical source than Kabuki and Noh, the consultation came to the National Theater and they offered shomyo as an answer. The resulting overseas tour was a very important experience for us. - What was the response overseas?

- I’m sure that the audiences were surprised by our performances. It was so different from what people think of as music and it seemed that it was a shocking experience for many people. What’s more, the piece we performed was Daihannya Tendoku-e (*4) , which is a chant where we literally shout. For Europeans, music usually means singing beautifully in harmonious chords. But this particular shomyo chant is one to drive out demons, so it develops into a harsh shouting. It is completely different from their concept of music. It was troubling to some, but from others we heard the response that they were surprised to discover such a wonderful music tradition from the Asia. Experience such a powerful response, we realized that it was a waste to keep shomyo shut away in temples.

- What was the other priests’ response to the overseas tour?

- At such famous venues as the Beethoven Hall in Germany, Priest Aoki was hailed as a great musician. In ancient times, you had to pass a difficult national examination to become a priest and shomyo was a major subject on that exam. Furthermore, the only people besides priests who could listen to shomyo were people from the aristocracy, beginning with the Emperor and extending to people of high education, all of whom had well-trained ears when it came to music. Only compositions with a very strong musical essence could satisfy such ears. Surely the priests felt the responsibility of this tradition and devoted themselves whole-heartedly to the pursuit of their chant. After the Meiji Restoration (in 1868 when Shinto was reinstated as the national religion) shomyo lost importance and became little more than a ritual practice within the temples. Despite being time-honored tradition, the intent to have shomyo be heard by the people was lost. So, after performing at the National Theater and receiving such acclaim on our overseas tour, we were awakened to the fact that we should devote ourselves more seriously than ever to the art of shomyo.

- Was there any notice of shomyo as a form of music before the opening of the National Theater?

- By the Meiji government (Meiji Era: 1868-1912), the reinstatement of Shinto as the national religion and the consequent suppression of Buddhism brought a big blow to the Buddhist community. At the same time, with the progress of Japan’s so-called Western-style modernization, the focus of music education in Japan was shifted completely to Western music and traditional Japanese music disappeared from public educational institutions. This continued until after World War II, when people like the contemporary music composer Toshiro Mayuzumi rediscovered Japan’s traditional music. People like him had studied music in the West and come to feel the limits of Western classical music for themselves, which in turn led them to look once again to their own country’s music traditions. Mayuzumi fell in love with the sound and resonance of the Buddhist temple bell, the sutra chanting and shomyo, and in 1958 he composed the work “Symphony Nirvana” that takes shomyo as its basic inspiration. This is a piece that can be considered an epoch-making work in contemporary music. It is a requiem prayer for the people who died in World War II and it deals with one of the most important Buddhist themes, Nirvana. Also, scholars of ethnic music like Fumio Koizumi became interested in shomyo and efforts were directed toward searching out shomyo scores (hakase) and making recordings of shomyo chanting.

- It is very interesting that avant-garde contemporary composers should rediscover shomyo. When were the first new shomyo pieces composed for performance in theaters?

- The first one to be performed was the piece “ A l’Approche du Feu Méditant ” composed by the French contemporary composer Jean-Claude Eloy and performed at the National Theater, Tokyo, in 1983. Eloy had come to Japan many times and had composed numerous works in the ancient Japanese court music (gagaku) style. Before that, the National Theater had produced experimental performances of contemporary compositions for gagaku and I believe that they decided to do the same with shomyo as a traditional Japanese vocal music form together with gagaku as a traditional instrumental music form. It was the National Theater producer at the time, Toshiro Kido, who commissioned the Eloy work.

- What was Eloy’s composition like?

- A L’Approche du Feu Meditant was an incredibly long piece that took three hours to perform in its entirety. He also composed a new work titles Anahata in 1986 in a form that was something like a game. He selected a group of verses with respective melodies and told us to choose freely from them and chant in an improvisational way. It was a work that reflected Eloy’s believe that music is not something set and fixed but something that is constantly fluid with the seasons and weather and performers’ feelings. There we were, these priests who knew nothing about music until then being made to rehearse until 1:00 am at the theater in one of the busiest times of the year when we had Buddhist services to be performed during the equinoctial week [laughs]. But this encounter with Eloy was a very important experience for us.

- Since Eloy, you have worked with a number of different composers. What are some of the main works you have performed with them?

- In 1984 we performed the new work Kaeru no Shomyo (Buddhist Chant of Frogs) composed by Maki Ishii using a poem by Shimpei Kusano. We have worked together on compositions by more than 20 leading Japanese contemporary composers, including Toshio Hosokawa with the piece Tokyo 1958 (1985), Yuji Takahashi with Yume no Kigire (1987) and Kazuo Yoshikawa, Yoshio Mamiya, Mamoru Fujieda and others.

- How have the participating priests approached these experimental projects?

-

We have always found it very interesting [laughs].

On our 1973 world tour the contemporary composer Maki Ishii was with us and he performed his piece Choetsu (Transcendence), which had no score and involved him banging on the piano, strumming harp strings and making us blow the Buddhist ceremonial conch shell that none of us were really practiced at blowing. It looked artificial and untrue in some senses, but it was interesting to us. With avant-garde musicians of that time like John Cage, it was clearly a world where “anything goes.” I think it was fortunate that that was our initial introduction to music. - What do you think was the attraction of shomyo for these contemporary composers?

-

I think it is the fact that there is a “voice” that is different from anything in the West. It wasn’t that they were out to create finished musical compositions with their new shomyo works, but that they needed “the voice of shomyo” with its background of Buddhist thought in order to give expression to an abstract world such as “the sound of the universe.”

The word anahata that Eloy used in the title of one of his works apparently means “vibration of the universe” and the instruments he used in that piece were ones with very unstable sounds, like the oshichiriki of gagaku . It is a historical coincidence that shomyo remained in Japan, but there is nothing uniquely Japanese about the voice of shomyo. I believe it is a pan-Asian sound with a rich expansiveness that is based in the culture of Buddhism that spread throughout Asia. The combination of the sounds of a number of priests with different individual voice qualities creates a unison characterized by slight discrepancies in tone, which in turn creates harmonic overtones. I believe that this unique resonance of shomyo has been the biggest attraction in shomyo for these composers. - In 1997, you and the other priests who had performed at the National Theater formed the group named “Shomyo Yonin no Kai.”

-

This was the result of desire to expand our range of activity and we had the backing of Mr. Kido’s successor, the director Hiromi Tamura, so we said, “Let’s do it.” The members of the group are the same ones who performed at the National Theater in 1973, including myself and Yusho Kojima of the Shingon sect and Koshin Ebihara and Jiko Kyoko of the Tendai sect. If shomyo is seen purely as a religious activity it is difficult to cross the boundaries between the sects. But taking advantage of the theater performance environment to work with members of other sects gives us a chance to brainstorm and develop our thinking about shomyo and to carry out activities more openly outside the religious realm.

In 2003 we added some of the younger priests who had performed with us and changed the group name to “Shomyo-no-Kai – Voice of a Thousand Years.” As the original four of us get older and our growing responsibilities in the temple make us busier, and the younger priests skills rapidly improve through participation in our regular concerts, this move is also serving to hand over the leadership to the next generation.

At the concerts we also do things to help people become more familiar with shomyo, such as giving lectures for those listening to shomyo for the first time and giving demonstrations to let the audience hear the difference between the voices of the different sects. As new works of contemporary shomyo we have performed the works A Un no Koe and Sonbo no Aki by Ushio Torikai and new works by Atsuhiko Gondai, Rikuya Terashima and others. This encounter with contemporary composers and musicians exposes us to new ways of thinking and new forms of expression that we are grateful for. - Finally, please tell us what you foresee for shomyo in the future.

- It can be said that Japanese shomyo is the traditional music with the largest geographical and historical spread of all Japanese music forms, because it includes elements that came from India and China. When you look at all the shomyo chants we are keeping alive and preserving today, it amounts to a veritable living history of music. Furthermore, shomyo is involved in all the ceremonies that take place at our temples during the year, which means that the tradition is being carried on as the chants are sung year after year. Shomyo possesses this built-in mechanism to successfully keep the tradition alive. On the other hand, when you consider the fact that the chants of the shomyo repertoire that were created in the Kamakura period and are now considered classic were in fact new pieces at the time they were composed, it is natural that we today should be making new pieces to add to the repertoire. I want to see us continue the challenge of pursuing the possibilities of shomyo as a precious and unique asset of Japanese music.

Kojun Arai

Interview with Kojun Arai -- Bringing the music of the thousand-year-old shomyo chant tradition to concert hall audiences

Kojun Arai

Born in Saitama Pref. in 1944, Arai completed the graduate course in literature at Koyasan University with a major in ancient Indian religion. He studied Busan Shomyo of the Shingon sect under Grand Priest Yuko Aoki and since has performed traditional and contemporary words of shomyo, gagaku and music at the National Theater, Tokyo, and widely, including foreign tours. He has performed in the 1973 “Japanese Tradition and Avant-garde Music” world tour, the 1986 Berlin Invention Festival and France’s Autumn Arts Festival, the 1990 Donaueschinger Musiktage Contemporary Music Festival and the Sydney shomyo performance of the 2006 Japan-Australia Exchange Year program. In 1997 he joined with Tendai sect shomyo performing priests in establishing the “Shomyo-no-kai – Voice of a Thousand Years” (successor to the Shomyo Yonin no Kai) group and worked actively to preserve and promote the spread the performance and appreciation of the ancient works and of shomyo while also working actively to encourage the production of new shomyo works. As a researcher of the Ueno Gakuin Japan Music Document Research Institute, he also researches shomyo scores. He is a guest lecturer at the National Music University. He is also a member of the Kalavinka shomyo research group. He is head priest of Hogyokuin temple in Tokorozawa city, Saitama Pref.

The Buddhist Monks’ Choir “Shomyo Yonin no Kai” Founded in 1997 at the suggestion of National Theater Director Hiromi Tamura and the Kaibunsha producer Junko Hanamitsu, this group was launched as a ecumenical gathering of shomyo performing priest led by Kojun Arai and Yusho Kojima of the Shingon sect and Koshin Ebihara and Jiko Kyoko of the Tendai sect. The group works to introduce classic works from the shomyo repertoire while also encouraging the production and performance of new works of shomyo through its regular “Spiral Shomyo Concert” Series. In 2003 the group name was changed to “Shomyo-no-Kai – Voice of a Thousand Years”.

Until recently, shomyo was only heard in temples, as monks chanted the Buddhist scriptures in chorus as a form of meditation, but now there is a group of priests who have undertaken the challenge of bringing performances of shomyo to the concert hall and enlisting the talents of contemporary music composers to create new works for the shomyo repertoire. We spoke with Kojun Arai, Head Priest of Hogyokuin temple of the Buzan branch of the Shingon sect and a leading member of this performance group called “Shomyo-no-Kai – Voice of a Thousand Years” to learn about the past and present of shomyo.

(Interview by Junko Hanamitsu on April 27, 2007 at Hogyokuin temple, Tokorozawa city)

*1 Shichi Bongo no San

A verse of scripture praising the wisdom and virtue of Buddha, transcribed from the Sanskrit into Chinese characters, chanted in original verse with original phrases. Shichi Kango no San is the one which is transcribed into Chinese and arranged in Chinese style.

*2 Shari San Dan

A verse of scripture in adulation of the Buddhist relics (bone fragments of the Buddha, Sakyamuni) as blessed remnants. It was composed by Ennin, the priest who brought Tendai shomyo to Japan from China and is the oldest shomyo chant in Japanese that has been handed down through the Tendai sect. It is chanted in the “Jorakue” (Nehan) ceremony commemorating the Buddha’s attainment of Nirvana, which is a ceremony where priests and lay people worship the Buddha together and therefore uses many Japanese shomyo such as Shiza Koshiki or Shiza Kowa San that can be understood by the listeners.

*3 Shiza Koshiki

A chant created by the priest Myoe Jonin in the Kamakura period (13th century).It is composed of four formulas, a Nehan Koshiki celebrating the Buddha’s attainment of Nirvana, a Rakan Koshiki celebrating arhat, an Iseki Koshiki and a Shari Koshiki celebrating the relics. The koshiki are scriptures in Japanese and are the roots of Japanese recitation story telling.

*4 Daihannya Tendoku-e

Also called simply Daihannya , it is a Buddhist ceremony to pray for world peace, peace and security of the nation, protection from disaster and good fortune and for good crops by reciting the 600 verses of the Prajna Sutra. As a sutra telling the true teachings of the Buddha, this 600-verse Prajna Sutra was written in transcribed Chinese characters in 663 by the Chinese priest Genso Sanzo after a 16 year journey to India dramatized in the famous story Saiyuki ( X_yóu Jì in Chinese, Journey to the West in English). Initially each character of the sutra was read, but eventually that long process was abbreviated into fanning the folded pages of the sutra text through the air while reciting the Prajna Sutra incantation (chant). It is a ceremony that combines musical and dramatic elements to the large-voiced chanting.

Hakase of Tendai Shomyo

Hakase of Shingon Shomyo

Oldest hakase

Jean-Claude Eloy’s

ANAHATA

Hogyokuin

Related Tags