- About how many care-givers and doctors from the facilities were there helping the handicapped performers during this production?

-

It is not easy to give a clear number. There are some of the more severely handicapped who needed two care-givers. Generally speaking there were about one directing assistant (care-giver) for every five handicapped players on stage while the play is in progress. There were also seven or eight stagehands doing the set-changing work. They help with the script prompting and follow-up on the actors’ movements and manning the wings to make sure that nothing dangerous happens. They are needed to bring out and remove the props and do the set changes.

All of the stage assistants and staff who worked with us this time have jobs of their own and were working with us purely on a volunteer basis. So I made it a point to move into the facility’s dorm ten days before the performance, but there were some who couldn’t join us until just before the performance. - How did the theater activities at the Azami Momiji Ryo facility begin originally, and how did you become involved?

-

I have heard that it began when my teacher at Osaka University of Arts, professor Satoshi Akihama, was still working at Iwanami Film Studio and visited the “Biwako Gakuen” facility for children with severe physical and mental handicaps in Shiga Prefecture in order to gather scenario material for the documentary movie

Yoake Mae no Kodomotachi

(Children Before Dawn) that was set in the facility. The Shiga connection may have come from the fact that Akihama’s wife was from a family that ran a nursery school in the prefecture.

When that facility was moved to its present location, they asked professor Akiyama if it wouldn’t be possible to have the patients do theater. The first play was then staged in 1979. That was before I entered university, so don’t really know anything about that period. Still, I was told that a professor Masato Tanaka who taught child psychology at Kyoto University interviewed the facility’s children before and after the play and found that in some of the more notable cases there were children so severely underdeveloped mentally that when asked to draw a person they drew a figure with the arms and legs coming directly out of the head. But after the play they drew a proper figure with a head and trunk with the arms and legs coming out of the trunk. This verified what a dramatic effect involvement in a play could have on a person’s development and what a valuable experience it could be. After that they began doing small plays at times like Christmas and the Dolls Festival with professor Akihama giving them advice. Then they began doing larger plays once every five years with professor Akiyama directing them.

It was the second of those plays that I went to help with for the first time. It was in 1984 when I graduated from university and professor Akihama asked me to give him a hand. After that I participate in those plays once every five years.

During that time the number of students taught by professor Akihama at Takarazuka Kita High School and Osaka University of Arts and those he instructed in the Piccolo Theater Company had grown and more people from among these former students began volunteering to help out with the plays, participating in the rehearsals for several days and sometimes working all night to build the sets.

As volunteer they didn’t get paid but they could stay in the facility’s dormitory and eat together with the patients in the cafeteria. People in theater are usually poor and they knew that if they came there to help out they could at least eat better than usual (laughs).

For this year’s performance I came to the dormitory on the 8th of November. There were fifteen or sixteen of us who were there from that time until the performance on the 19th. The other volunteers came to help when they could. The schedule involved rehearsals from 1:30 in the afternoon, and when the rehearsals were over we would work late into the night building the sets. Then the next morning we would have our staff meetings and from 7:00 in the evening we would do our operating rehearsals. - In short, there have been five different productions of these big performances over the years. Is that correct?

-

That would be correct. Some of the patients who were in their 30s when we started out are now in their 60s or 70s and some of them have become a little unstable on their feet. When we did the last play five years ago we were saying that it would be the last one because it was getting just too physically demanding for many of the patients. But after the play was over they started to talk about doing another, saying how much they wanted to do it again. So we ended up doing it again this year.

Socially speaking, during this time things like the passing of bills to support the handicapped in becoming self-supporting have led to budget cuts for facilities for the handicapped, and the former Governor of Shiga prefecture, who supported our activities, has been replaced. As a result the environment for these kinds of activities for the handicapped is actually worsening. Shiga Prefecture has been called a paradise for the handicapped because it carries on the traditions of Mr. Itoga, the pioneer of welfare services for the handicapped who established the country’s first facilities for the handicapped in Shiga just after World War II. But, in fact, from what I see that situation is very tough today for people working to provide welfare for the handicapped. - How did the activities we see today in the Itoga Memorial Performing Arts Festival come to spread throughout Shiga Prefecture?

-

We had actually planned to have our once-in-five-years play last year, but we couldn’t get the funding. So, we decided to do a tie-up with the annual Itoga Music Festival and it happened to be the 10th anniversary of the Itoga Memorial Awards that recognize people working in the field of welfare for the handicapped and so people stated talking about making it a bigger event than usual.

Combining music and theater in this way would make it easier to finance and we could involve patients from other facilities besides the Azami Momiji Ryo facility in the performance. Professor Akihama wanted to see that kind of development, I believe. - But Mr. Akihama passed away suddenly, didn’t he?

-

Yes. After initiating this proposal, professor Akihama passed away suddenly last summer while on a tour to see how the eight participating groups from the different facilities were doing with their preparations. I had planned to help out after the script had been completed, but he passed away before the script was written!

Originally this was to be a work that only professor Akihama could have done. So what would happen after his death? We started asking ourselves, it was time for his former students to carry on what he had started. This was originally a program that professor Akihama had started and this year’s performance was to have been the culmination of some 30 years of efforts, so we knew he would have wanted the project to be carried through with.

Then professor Tanaka also passed away last autumn, so the program had suddenly lost its two biggest leaders. - So you took over as a sort of pinch hitter?

-

That’s right. As soon as my company had finished with its summer production, I planned a trip to see what the eight performance groups were doing. But, when I actually saw what the different groups of patients were involved in, I actually had doubts about whether or not it could all be brought together into one theater performance.

Although we used the series of Adventures of Robin Hood for the play they were doing at the Azami Momiji Ryo facility, the contents of the play were actually events that had happened at the facility and topics from their daily life. But this time we had to work in the other performers doing music or dance, and to do that there has to be a story line to connect the scenes into a whole. For connecting scenes into a story, a script of spoken lines is necessary, but we didn’t know if these patients could memorize and deliver lines. So I had to think about what kind of script they could handle. - It was a three-hour performance and I thought that the story was carried along very well with narrators like those used in traditional Japanese Kyogen theater.

-

The people who did most of the speaking of the lines in the script were the patients from the Azami Momiji Ryo facility who had experience doing the plays in past years and whom I have worked with for many years. In the case of the other players, I thought that if you use an interview format you could get them to deliver lines even if they couldn’t memorize them. For example, if you ask them “What’s your name?” or “What is your favorite thing?” they can answer, and that becomes effectively the same as reciting lines written in a script for the participants who have been doing music or dance.

The important thing is the response from the audience to those words when they are on the stage. It is the response. The important thing is that being on stage makes them seen by people, that the play makes them focus of the attention of other people. Whether it is laughter or applause or a questioning “Hey?” the important thing is that there should be some reaction and that the players experience the feeling of being the focus of people’s attention. When this happens, even children who are quite withdrawn can become more outgoing. They become more inclined to initiate action. I have been watching this process for 30 years, so I wrote the script with the aim of giving every player at least one line or one word to say.

Mr. Itoga used to say, “People become human beings when they are among people.” Within the confines of the a facility like Azami Momiji Ryo there are few occasions when the patients can feel that their presence is being appreciated by others. But when they have the courage to stand on the stage and deliver even one line it opens a new door and it expands their world. So our aim is to use any means we can to give them a chance to say something, say one line on the stage. We all work to get them to speak. We try to get them to stand once in the front line on the stage in a situation where the audience will respond to them. This experience is sure to bring a dramatic development in their behavior. That is what we tried to do. - You were also able to coordinate the costumes and makeup, weren’t you?

- We are told that when the patients who are doing music performance they were never coordinated costumes or makeup. So they were all very excited to have costumes this time. But in the final dress rehearsal the day before the performance we had them in costume, but we saved the makeup until the actual performance day, because if we didn’t have something new it would just be a repetition for them.

- Does this experience working with the handicapped people have any influence on your regular theatrical activities with your company Gekidan Minami Kawachi Banzai Ichiza and the workshops you do around the country?

-

What impressed us so much was the genius of their performances. We all felt it from the very beginning. Without any self-consciousness they could deliver amazing performances such as we never expected. We couldn’t help but think that behind their innocence that actually knew how to act. Their performances went beyond what we think of as acting. And, in that sense, there is a lot that we can learn from them as actors.

Particularly when I was just starting out in theater in my twenties, there was a lot of competition to try to stand on stage with a style that set you apart from the other actors and the other companies. And in my case, a lot of the things I did were actually imitations of our actors at the Azami Momiji Ryo facility (laughs). That anarchy, that inscrutability—I borrowed a lot from them. - The patient who played the lead in our Azami Momiji Ryo plays had an amazing memory. She could do things like recite all the names of the train stations around Lake Biwa.

-

She is truly a genius with an amazing store of facts she has memorized. If you ask her what day of the week November 6, 1951, was she can tell you immediately. It is as if she has a calendar imprinted in her mind.

Besides that amazing memory, she also has the ability to act in a calculated way. To teach her lines I rely on a doctor who has worked with her for 40 years, and sometimes she will pretend that she has forgotten the lines he has taught her when practicing and make up an excuse for why she forgot it, like “That day such-and-such happened, so I couldn’t get it right today.” But, when it comes to the actual performance she will throw in an ad-lib like “And now professor Akihama and professor Tanaka are looking down on us from heaven.” It is something that isn’t in the script and she has never said during the rehearsals but saved for the final performance day and the audience loves it and she is really enjoying herself. But it makes the director pull out his hair in anguish (laughs). - It is indeed fascinating to know that there are people with such talents.

-

You will be amazed at how many people with exceptional talents there are in a facility like this. That women is autistic, but autistic patients have good times and bad times and if they aren’t able to do the things they feel they have to do everyday they get very badly thrown off balance. So you can’t just make them do rehearsals as you would like them to. If they have a fit it will completely disable them and even when they may be smiling as they say their lines, if they think they have not done it right they may suddenly start screaming and pound on a table until they break three fingers. You never know when someone is going to explode. So we always consult with the facility doctors to know when it is all right to practice. They get better and better as the performance approaches, but if someone explodes everything is ruined. So it is absolutely essential to keep in constant communication with the medical staff.

For the patients, the rehearsal period is one where these strangers have come to stay in the dormitory and work with them, so there is a lot of stimulation they are not used to and it is easy for them to get into a high state. That is why it can be dangerous to overdo it. Still, we want to make an enjoyable play, so we are unavoidably walking a thin line.

In the years when we do the plays, the facility’s doctors help out by encouraging the patients to join in the play and trying to build their motivation. And if they have a half a year, they can prepare themselves. For example, there was one of the patients who was to take part in the role of a maid as one of the narrative parts. She is also autistic and she never came to any of the work sessions before the final rehearsals, but it seemed as though she was preparing herself for the role. However, even her care-givers didn’t know if she was preparing to take part in the play or preparing not to take part in it.

We didn’t know what she would do but we wanted to give her a role with lines to speak, so we gave her a simple role in which all she had to do was respond “Yes. I think so.” when someone asked her “Maid, do you think such-and-such?” And we had prepared to be ready to just move on to the next lines if we got no response from her.

When it came to the final rehearsal, however, she did do her best and said her lines. In the actual performance she managed to get out on the stage and perform for us, but part way through, she had to leave the stage. We could see that it was just too much for her and we thought that was the end of her participation. But after a while she managed to get herself back on stage and say her part. And it isn’t just her. All the participants are battling with themselves to get up there and perform. It is really rewarding for us to see them making that effort. - Even if we don’t go so far as to call it “theater therapy,” I think the theater world should recognize the significance of what you are trying to do.

- I think professor Akihama was ahead of the times with his efforts in this program. We are seeing an increasing number of cases know where theater is being used to achieve some kind of effect with people who have problems or handicaps, and professor Akihama was certainly a pioneer in this field. I recall one time when I was younger, professor Akihama scolded me in a very severe voice, saying, “What if something happens to that child while you are trying to get them to do that!” He said it in a voice that frightened all the patients and staff present. But looking back I realize that was also part of the fundamental theater experience he wanted us to have.

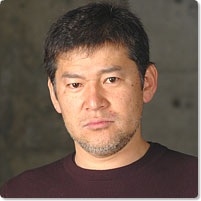

Hironori Naito

Hironori Naito talks about 30 years of theater projects with the mentally challenged

Hironori Naito

Head of the Minami Kawachi Banzai Ichiza theater company, Hironori Naito was born in Tochigi Prefecture in 1959. He began to pursue a profession in theater after seeing The Jokyo Gekijo production of Hebihime-sama (written and directed by Juro Kara). He entered Osaka University of Arts (theater dept.) in 1979, where he was taught by professor Satoshi Akihama (playwright and director) for four years. During that time he pursued the study of what he calls the “How to cheat with realism.” In 1980 he established the Minami Kawachi Banzai Ichiza theater company, directing a production of Juro Kara’s Hebihime-sama as the company’s inaugural play.

Acknowledged for the broad perspective he brings to his modern-style plays that survey the issues of contemporary life, Naito also writes and directs often for productions outside his own company. Among these, he has done the planning and directing of unique nationwide tour of the world-famous pianist Ikuyo Nakamichi.

In 2000 he won the Outstanding Director Award of the Yomiuri Theater Grand Prix. for the OMS production of Koko kara wa Toi Kuni (A Country Far from Here). In 2005 he directed a production of Chokyoshi (by Juro Kara) at Tokyo’s Theater Cocoon and the Hyogo Performing Arts Center. Since 2003 he has been pursuing theater activities ambitiously at the Ultra Market (Osaka Castle Hall, West Warehouse) since the closing of Ogimachi Museum Square, which had been his base of activities. Recent works include Hironori Naito’s Gekifu-roku Part 1 (first collection of Hironori Naito plays) and Aoki-san chi no Okusan (Wife of the Aoki Family).

The theater had been greatly modified, with all the seats removed from the front third of the theater to make a large area for wheelchairs, and a slope had been installed at the front of the stage to enable easy access onto the stage. The director had set a place for himself at the center of the front row of the wheelchair space to direct the play from. The handicapped performers in the play were seated up on the stage facing the audience in a stand-by position so that they could watch the play with the audience until it was their turn to stand up and act out their part or participate at times from the stand-by position.

Borrowing a story about a group of penguins that have forgotten what they were supposed to be looking for and end up going on an adventurous journey in a play that the mentally challenged players and audience could enjoy along with the normal audience, laughing, enjoying the games and in the end celebrating the joy of being alive. To find out how such a lively, enjoyable play could have been put together even though the eight performer groups had only performed together on the same stage for the first time at the previous day’s dress rehearsal, we talked with the play’s director, Hironori Naito.

Interviewer: Norio Koyama

*Satoshi Akihama

Born in Iwate Pref. in 1934, Satoshi Akihama graduated from the Drama Dept. of Waseda University. While still a university student in 1956 he wrote the play Eiyutachi (Heroes). After graduation he worked for the Iwanami Film Studio for eight years. From 1962 to 1973 he participated in the theater company Gekidan Sanjuninkai, working on productions including Horanbaka (1960), Tomin Manzai (1965) and Shirake Obake (1967). In 1966 he won the Individual Award of the 1st Kinokuniya Awards. In 1969, he won the New Play award of the Kishida Drama Awards for Yojitachi no Ato no Matsuri (1968). From 1979 he assumed a teaching position in the Theater Arts Dept. of the Osaka University of Arts, and in 1994 he became the first director of the first prefectural theater company in Japan, the Hyogo Prefectural Piccolo Theater Company, where he continued to educate young theater people and direct plays. In 1998 the achievements of the Piccolo Theater Company were recognized when they received the Company Award of the Kinokuniya Awards and the Japan Arts Festival Prize for Excellence by Agency for Cultural Affairs.

After retirement in 2003 he continued to participate as an educational advisor in the Piccolo Theater School. He passed away in 2005.

*Kazuo Itoga (1914-1968)

A pioneer in the education of handicapped children and in social welfare programs in Japan. Born in Tottori Pref., Itoga attended the Imperial University of Kyoto, where he majored in philosophy in the Literature Dept. After graduation he began working in the Shiga prefectural government. After World War II he established the Omi Gakuen facility for war orphans and mentally handicapped children. Later he established the Biwako Gakuen, the first facility in western Japan for children with severe physical and mental handicaps, and numerous other facilities. At the same time he worked to build the nation’s social welfare system through his positions as a member of the Central Children’s Welfare Deliberative Council’s Welfare Council for the Mentally Handicapped and president of the Inclusion Japan (Japanese Association of/for People with Intellectual Disabilities). He approached welfare education with the belief in “Making these children a light for the world.” For these activities, Itoga is known as the leader in establishing social welfare for the handicapped in Japan. His spirit I carried on by many social welfare workers today and in Shiga prefecture where he spent most of his working life, an Itoga Memorial Foundation has been established with the aim of passing on his heritage to the next generation of welfare workers by recognizing outstanding contribution in the field of welfare for the handicapped through an awards program and conducting educational, training, survey and research programs aimed at raising the quality of welfare activities for the handicapped. Among his main publications are Kono Kora wo Yo no Hikari ni (Making These Children a Light for the World), Ai to Kyokan no Kyoiku (Education with Love and Sympathy), Benkyo no Nai Kuni (A Country Without Education), Seishin Hakujakuji no Shokugyo Kyoiku (Vocational Training for Mentally Handicapped Children), Seihakuji no Jittai to Kadai (Status and Issues Regarding Mentally Handicapped Children) and Fukushi no Shiso (Welfare Ideals).

Robin Hood—Rakuen no Boken

(Robin Hood—Adventure in Paradise)

(as part of the Kazuo Itoga Memorial Performing Arts Festival)

Novemer 11, 2006 at Ritto Center for Fine Arts, Sakira

Written and directed by Hironori Naito (Minami Kawachi Banzai Ichiza)

© Shiga Prefectural Social Welfare Corp.

Related Tags