The beginning of Phare

- Phare, the Cambodian Circus (Phare) has been presenting original work every day since 2013 at its own big top in Siem Reap, where tourists come to see Angkor Wat, and functions as a social enterprise to raise funds from ticket sales. Can we begin with how the NGO Phare Ponleu Selpak (PPS), which offers arts and education to the unprivileged community, created Phare, the Circus? How did it all begin?

- The story of Phare is indeed quite a tale. It is hard to imagine that what it has grown into today had such a humble beginning. In 1986, a young French art teacher named Veronique Decrop volunteered to work at refugee camps along the Thai-Cambodian border and taught arts to the children to help them cope with trauma.

In 1991 when the Paris Peace Accords were signed, all refugee camps had to be closed, and those who did not migrate to a third country were urged to return to Cambodia. Thousands of people who had left their land and property before the war were unable to reclaim ownership when they returned. Having their homes and land taken away, many of these former refugees decided to settle in Battambang near the Thai border, thinking they might need to escape again should another war start. During the rule of the Khmer Rouge, those who had knowledge, those who could speak foreign language, teachers, doctors, government staff, writers, singers and musicians were the first to be killed. We don’t know the exact number, but it is believed that 90% of intellectuals in Cambodia were killed. When it was liberated, we found our nation traumatized, paralyzed, and filled with women and children. Those who could read and write started to teach others, because we had lost all our teachers. The young generation did not even know their own country because many of them had spent close to 10 years in refugee camps. Some promised to travel by foot to meet each other again without knowing how far away each city was. This was year zero for Cambodia.

It was in these circumstances that many young people learned to draw from Veronique, as she stayed in Cambodia for a long time. Among those who learned from her, 9 young people decided to work together with their teacher and use their art skills to contribute to the rebuilding of Cambodia. They started giving free painting and drawing classes under a tree, which became the origin of PPS. The tree is still standing today inside our school in Battambang. Some members gradually found that many young people also wanted to jump, run, dance, and express themselves with their bodies. One of our founders, Khuon Det, had the opportunity to study at the National Circus School of Cambodia in the 1980s. He then initiated a performing arts program within PPS when he came back in 1998: first music, then theatre, and then the circus. Khuon Det is now a director of performing arts in PPS, which now has 4 disciplines, including dance. - How did you spend your childhood, while the PPS founders started to teach art under a tree?

- I was born in Siem Reap in the early 1980s and grew up in Battambang. Growing up in Cambodia at that time, I still clearly remember hearing the propaganda radio. They played lots of songs about blood: blood of the farmers, of the workers, of the revolution. I was born after the Khmer Rouge, but I grew up hearing stories of how people lived through it. It was actually my bedtime story, because my mother used to tell me of her experiences before I would go to sleep. How she survived, what she ate, and how she picked up the habit of smoking to get some rest from farming as those who smoke were allowed to take short breaks.

Like my mother, Khuon Det also lived through the Khmer Rouge. One of his productions, Sokha , is based on his experiences. The production still brings me to tears when I see it, as the imagery is very vivid even to my generation. I am worried that if we don’t do enough to teach our children about it, history may repeat; people might forget what happened and make the same mistakes again.

I first experienced arts and culture through radio. When I was growing up, I used to like listening to “speaking theatre,” or audio drama, on the radio. It was so fascinating I even asked my mother if we could go meet the voice actors. We could not, because at that time there were no theatres in the city, so to me those actors only existed within the radio programs. In the 2000s, this speaking theatre culture died out naturally. Another thing I enjoyed as a child was going to the cinema. Bollywood movies were so popular that some people even named their children after Bollywood star, Officer Govinda. Everyone rode bicycles or motorbikes to the cinema, which was nothing more than an outdoor space surrounded by curtains and a film projector. Around this time, Cambodian cinema was flourishing, but that industry also seemed to have died out when TV culture arrived. What became popular instead were Thai dramas and Hong Kong action movies on TV. At that time, my family was doing very well in business, so we were the first in the village to own a TV. The whole village gathered at our house every night, and some children even stayed overnight. It is a very special memory to me, and I still remember it very well.

However, I still remember some hard times as well. People think that the Khmer Rouge ended in 1979, but even around 2001, they still controlled parts of Cambodia. The areas near the border with Thailand were the last battleground. In village area where I lived, remaining Khmer Rouge would come to steal from people. So when we heard gunshots, we would run to our underground shelters: every household used to have one out back. We just grabbed what we could: water, food, and rice, and hid underground, sometimes for several days, until it was quiet outside. I also used to hear on the radio, “Success, success, we killed our enemies!” Their enemies were the Vietnamese, Capitalism and America, but it also meant Cambodians killing other Cambodians. They sounded very proud, but even when I was young, I wondered: “But why is killing each other a success?” That was also part of my childhood. - Those stories seem hard to believe, looking at what you have become today at Phare. What were your cultural influences other than radio and cinema?

- There is another thing I liked: the travelling circus. They still exist in Cambodia today, but only in very rural areas. They are called

Pahi

. Street artists who survived the Khmer Rouge formed troupes and toured from one village to another. They did acrobatics, magic, and used monkeys to make people laugh and cry, and then they sold medicine – traditional herbal medicine – instead of asking for payment for the performance. They came to villages almost every month, and they were amazing. I have very beautiful memories of them. There were many troupes, and some of them were famous among the villages, not because of TV or radio but through word-of-mouth. People admired some of the star performers like they do celebrities today.

Another similar kind of performance was Lakhon Bassac . Lakhon means theater, and Bassac is the name of a river. It is a traditional Cambodian fusion of Chinese Opera: they sing, do acrobatics and kung fu, while playing mostly Cambodian musical instruments. They were also very popular, especially at Pagoda festivals. When they would come, the whole village would gather: some children came early to get a good spot, and some even stayed and slept outdoors all night as the show went on. This form of theatre was very alive at that time. We used to have a joke – some of the characters in the performance were kings, so people used to say, “The poorest king in the world is the king in the theatre,” because after the performance they went among the food stalls at the festival to buy food. Those performances have always been supported through the patronage of wealthier families. At some point in my life it was my father who would bring artists to the village for everybody to enjoy.

Encounter with PPS

- You studied at PPS in the past. How did you become a student there?

- When I was in high school in Battambang, my friends and I used to ride bicycles together and go to PPS. We went there mostly to have some fun after school and on school holidays. The school mostly functions that way even today, except the formal education curriculum which started in 2004. Informal classes are open and free. If you feel like drawing, or playing music, you just go to one of the classes. I picked up music and learned the

Roneat

, a Cambodian xylophone. It is one of the most important instruments in traditional ensembles; you see a lot of those in our productions at the circus. I forgot how to play, but I used to remember which key to hit by remembering the assigned numbers, as PPS follows traditional pedagogy and does not use western notation.

After three months of learning music for fun, I helped PPS’s first international project as a translator. There were 7 artists from Europe, musicians, costume makers, scenographers, circus performers and so on, and they spent one week conducting a workshop to help young people learn. Some of the participants from the project, such as our artistic director Bunthoeun, still work for Phare today as directors of the shows.

After the workshop, we went on to our very first tour within Cambodia. It was called “an awareness tour,” which was intended to educate rural residents about AIDS, Malaria, dengue fever, and land mines. As many of those villagers only had access to the propaganda radio and were cut off from other forms of media, many people did not know about these things. The teachers in the group were mainly from France, and ever since the project began in 2001, they continued to come back and hold workshops with us. The group is now called Collectif clowns d’ailleurs et d’ici ( Clowns Collective from Around the World ). Today they have become a partner organization bringing PPS senior students on European tours twice every year. As we speak now, one such group is touring in France. Students who register in the formal course for performing arts will go on this tour before they graduate. The group functions as a partner to PPS, and helps raise awareness about our works in Europe as well. - It seems your language skill helped you open some doors, but how did you learn to speak English and French?

- I was born and raised in Cambodia, and studied English in Pagoda (temple); monks in the village were my language teachers. Traditionally, Buddhism was the center of education in Cambodia. In fact, when boys reached the age of 12 or 13, they were encouraged to go to Pagoda. Being a monk was the equivalent to being a university student, because as a monk, you are there to absorb knowledge. One becomes a monk not only for religious purposes, but also for the education they receive. After a person comes back from spending 10 or more years as a monk and becomes a layperson again, we call that person a “man-of-knowledge,” or Bandith in Khmer, which means doctor. We call them doctors, similar to what we call people who complete higher education and earn a Ph.D. It was quite common in my childhood for people to learn English not only in public schools, but at Pagodas for little or no cost. I studied French because my father wanted me to be a lawyer. Back then, French was the only language for law and medicine. Luckily, I was chosen to be part of a French government project, La Francophonie, to integrate the French language into formal high school education, as well as studying it at the French Cultural Centre.

Many people thought I was from a privileged family and went abroad to study; yes at some point my family was doing well in business, but also I grew up selling flowers with my mother in the market. The only thing I feel lucky about was having a strong-willed mother who pushed me to study hard. There are actually many affordable, accessible options for Cambodians to study. So whenever I speak about language, I always feel strongly obliged to tell young Cambodians that if they want a good career or want to be successful, they must study hard, especially English, and that being unable to afford it should not be an excuse. - I understand that PPS currently functions as a public school as well as offering arts classes. Can you tell us about how it is managed?

- Phare Ponleu Selpak (PPS), managed by our mother NGO, has evolved a lot over the years, seeing many changes, but even today they remain true to their original vision and mission with programs in three main pillars: arts training, social support and formal education.

In arts training, there are two departments: the Visual and Applied Arts School, which teaches fine art, animation and graphic design, and the Performing Arts School, which teaches circus, music, dance and theatre. There are 3 more founders still active in visual arts alongside Khuon Det: Srey Bandaul, Tor Vutha, and Lon Lao. They are considered the first generation of Cambodian visual artists to emerge following the Khmer Rouge.

Social support is a very crucial part of the school. This program allows us to help children from the most underprivileged backgrounds, or those suffering from neglect, abuse, and all sorts of problems. We want to provide not only education but also an environment that makes it possible to continue learning. We now work with 10 social workers, following 800 families in 3 neighborhood communes on a regular basis.

Most recently, the school started to offer formal education from kindergarten to high school. There are 4 high schools in the city including ours, but the 3 other schools have students mostly from middle to upper income families. In PPS, many things are offered for free, so we mainly have students from lower income backgrounds. At grade 8 or 9, many give up school because their family does not earn enough for them to continue to study. Many of them start working on the street, become laborers, start selling things, or migrate (sometimes even illegally, because they can’t afford legal working permits and passports) to Thailand to become construction workers. So, in our school as a whole, there are a lot of students in the beginning, but in the final year, grade 12, usually there is only one class. Among those students, only a few of them, usually 3 to 5 or so, will pass the final exam to receive their high school certificate. Other high schools would probably have 15 classes and most of them would pass the graduation exam.

Art curricula are offered in both informal and formal education. Students can go join any of the class for leisure, or they can enroll in a formal curriculum. The formal curriculum provides them a certificate from PPS, but it is not equivalent to high school certificate. We are hoping, and working, to be recognized as a vocational training school to be able to give a high school certificate or higher to arts students. - Are students from the Arts curriculum able to find jobs relating to their skills after graduation?

- We have 1200 students, which makes us quite large as a school, but not everybody is involved in the arts. Among those 1200, only a handful will choose art as a career. At our performing arts school, a full-time class would start with around 40 students, but by graduation, we usually have only 8 to 10. Some of them find other opportunities and leave, which is a good for them, and we hope they become supporters of the arts in the future. Some of them leave school and start working as laborers or construction workers. Many girls quit when they get married because their husbands or families expect them to cook and raise children at home. We have lost amazing female artists because of this. In fact, we are making enabling women to continue their careers after marriage one of the priority areas for our social workers.

So even if one loves it and has talent for it, it is a very difficult path to choose as a career. Phare has shown them that there is some hope, though it is not very sustainable yet, so if they have other choices, there’s no reason to stop them. We have very good contact with a former musician who is now a shop owner, and we always greet each other. In the end, the important thing for us is that they have good lives.

About Phare, the Cambodian Circus

- Phare employs graduates from PPS. How does Phare work? Can you give us an overview?

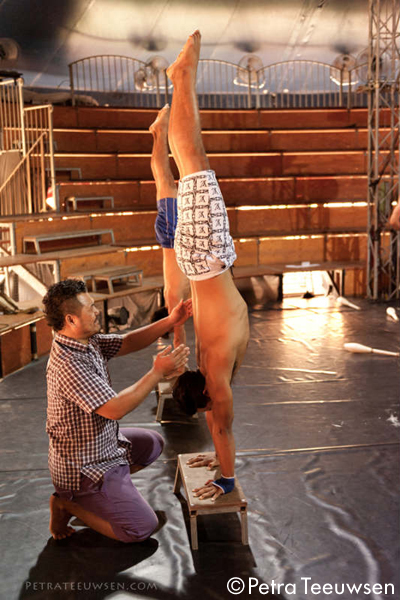

- At Phare, the Cambodian Circus, we perform full-length original Cambodian circus performances 365 days a year in our theatre, a big top with 330 seats in the city of Siem Reap. When we started in 2013, we strategically selected Siem Reap to target the 4 million tourists who visit Angkor Wat every year. We produce our own circus shows, using music, theatre, dance, and even visual arts, to tell unique stories based on Cambodian history, culture and society. We provide our customers a unique opportunity to see Cambodian culture, and at the same time provide employment to our graduate artists, with a mission to raise funds for the sustainable management of our NGO.

It is very important for us to be human, real, and grassroots. I have seen many different types of theatre and circus performances, including the famous Cirque du Soleil, but I think Phare is different and special, and being unique is definitely a good thing. If we had 3,000 seats instead of 330 it would make us so much more money, but we would not have the real, human connections that we have in our stage right now. That is why we have 330 seats, but turning that into a sustainable business model is a big challenge. How can we make this 330-seat theatre a model that is able to employ, say, 1,000 artists in the future? Planning for the future is very challenging, but our focus will always be on the development of our artists and employees, not only how to make the business grow. - I learned that images of acrobatic moves are inscribed on the walls of ancient temples such as Bayon Temple, suggesting it has been practiced in Cambodia for many centuries. The style of the circus produced in Phare is called contemporary circus. How important is it that the circus is in the tradition of Cambodia?

- Cambodia has as a whole experienced an identity crisis especially in circus arts. We have found through our research on the bar-relief carvings in the now UNESCO World Heritage site Sambo Prei Kuk and through traveling performing troupes such as Pahi, that there is a long history of circus and acrobatic performances in our country from as far back as the 6th century. But in our society after 90% of the intellectuals were killed, many of us are unsure about what tradition and identity in circus arts we can rely on. We might have not recreated exactly how it was done in tradition, but we were clear from the beginning about what types of circus we wanted to do. In 1998 when Khuon Det came back from his training and started circus training at PPS, the idea of contemporary circus was quite developed especially in Europe and Canada. We didn’t want to go back to using animals, but wanted to create our own unique style of performance.

Det and Phare emphasize the long history and focus on creating an original Cambodian production, because we want people to recognize it as part of our culture, not something entirely foreign. We still have a lot to do to raise awareness of this issue to the audience. - What is the direction of the production?

- At the end of the day, our basic principle is to define the needs of the people; they must be willing to come to the show and willing to pay for it. Today in Seam Reap, our target market is tourists, and they come to Cambodia only for 2 or 3 nights. We care about our artists and social mission but as a social business, I must also consider who pays for it. Today at this moment we won’t aim to take the risk of experimental, abstract shows even if they are deemed to have high artistic value in the art world. We need a performance that makes us proud, as well as keep our customers satisfied.

It was a big learning curve for us. We are trying to create a new production every year, and I think one production should not last more than 5 years. We hire artistic directors from inside and outside of the company when creating a new production, but there are times when we could not agree with the way it was going. In one case, it was very difficult for both the director and us, but after a long talk, discussion and rehearsal reviews, it was decided that we had to quit the production in the middle. It was simply too abstract for an audience seeking inspiration that we did not see our target audience willing to pay for it. We felt maybe we did not convey our needs clearly enough, so after that we created a brand guideline thanks to the great help from Mr. James Tan, my manager in the company I worked for formerly. The purpose of the guideline is to share what Phare is supposed to be and what it wants to be. We do not want to limit anyone’s creativity – we want everyone to be as free and expressive as possible, but there are certain feelings we want the audience to take back home after watching our show. So, from both a business and artistic perspective, we now give very clear guidelines to everyone in our team. - Increasing attention is being given to the notion of a “social circus” that deals with social problems such as poverty, disability or aging. Do you consider Phare to be a social circus as well?

- For us, it is very clear; we focus on the artists’ livelihood and our business, and we let our mother NGO, PPS, handle the social circus programs to deal with social welfare, mutual understanding and poverty. We do have community engagement programs, however, we perform in schools or in villages without charge, or invite school children and social groups in Cambodia to see our shows. These are the small things we do in our capacity as a social enterprise, but the NGO handles the program for human development through circus. PPS founded the Asian Social Circus Association in 2013 together with 5 other members. The association is still in the beginning stages, but I see a great potential in the network. When it comes to the point where the social enterprise finances most of the school’s budget, the school might be able to expand their social circus activities. Maybe they can reach international festivals, continue to visit slum communities, or drug rehabilitation centers to help people develop. Today we do things with what we have, but in the future when we grow as an organization, there are many things we could reach out to do.

- Can you talk about the Tini Tinou Festival? It started 10 years ago, many years before Phare was established. How did it start?

- Tini Tinou Festival is an international circus festival started in 2006. It was originally initiated by the French Institute of Cambodia, and PPS was a partner from the beginning. After 4 years, PPS took on the role of main organizer in 2010. For several years after that we could not afford the full program, but we re-launched it in 2014 with Phare the Circus as the main organizer. We had an audience of 4,500 spread across 8 nights in 3 cities. Over the years we had performances from Australia, Canada, Indonesia, Nepal, Japan and France. We are planning its return in May 2018, in Phnom Penh, Battambang and Siem Reap as 11th edition. Along with the international performances, we are also planning a Fringe Festival in Battambang as a new effort, to host performances and workshops by young Cambodian artists.

How Phare pursues its mission as a social enterprise

- Finally, I would like to ask about the social enterprise. In one interview you had expressed that you decided to join Phare because it was a social enterprise, not a not-for-profit organization, so that your experiences in business could be useful. Even so, it seems like a huge change of career. How did you decide to work for it?

- I was in business for 13 years. First I was in the airline business, and later involved in hospitality and tourism. I was proud to be one of the few Cambodians in a management position, holding equal responsible with the expatriates in the company. All my life, I had never even dreamed of working in the arts. In 2012 when Phare contacted me, I thought they were asking for a donation. But when I found out that they had actually approached me to run a new business for them, my first reaction was: “No way!” I was happily climbing my way up in my corporate career, and wasn’t intending to give it up.

I wouldn’t be sitting here today if I hadn’t taken the classes in Phare in 2001, and got to know the people there. I was interested because I knew them and I care for them. I knew how poor some of the children are, and I knew how those people have been helping the community where I grew up. Actually, it was not so out of the blue; we have kept up a good relationship for a long time, partly thanks to my career in airlines, as I used to see them quite often at the airport. From time to time they had been asking if I could help here and there. So after I heard this offer, I said no, but started to help them in my free time.

It took a year until I made up my mind. I was not sure how I could be a CEO suddenly. It was then that my ex-boss looked at me in my eyes and said, “Dara, you are ready. Go do this!” I was so surprised and confused as I always thought the company would not want me to leave. It was there that I learned in a big way that being a leader is not about surrounding yourself with amazing people and keeping them there; being a leader is being able to look at someone in the eye and say, “You can do this. Go do it!” That is what I continue to do in my business today. Even if I know it will be hard for me to let someone go, if I see that they have potential, I will encourage them to take the chance. - I understand that the initial idea of starting a social enterprise was back in 2008 when the global economic crisis hit the donors of the school. They expected a social enterprise to generate a sustainable income to support the school, as well as to create employment for the graduate artists.

- Our organization is formally called Phare Performing Social Enterprise (PPSE), and we manage the circus as our core business. We have also recently developed other businesses under that umbrella alongside the circus: the Creative Studio which offers services in graphic design, video, sound and 2D animation; the Handcraft Boutique which sells artistic products such as paintings, drawings and music from our artists, as well as locally produced ethical products from other NGOs; and Productions International which handles private events from hotels and corporates, as well as international tours. At the moment, we work with 47 artists and 70 staff members in PPSE on a regular basis including all the associated companies. We are registered as a private limited company, however, as there are no specific schemes for social enterprises in Cambodia. Our mother NGO, Phare Ponleu Selpak Association (PPSA), has been operating as a non-profit, non-governmental organization since 1994, almost 20 years before the circus was established, currently working with 110 staff members including teachers, social workers, administrators and managers at the school. Although PPSA (NGO) created PPSE (Social Enterprise), we operate independently with a different mission and management.

Last year the company posted our first dividend to our shareholders. As the school owns 71% of the shares, we distributed 126,000 dollars to them for the first time. So, while the school is not yet sustainable by PPSE, we now contribute about 22% of the school’s budget. In 7 to 10 years we hope to contribute 90% of their budget. - Who are the other shareholders? How do they influence your operation, and how do you make decisions between business and your social mission? What is your main role in it as the CEO?

- Grameen Crédit Agricole Foundation owns 17% of the shares. It is a microfinance and social business fund founded by Grameen Bank from Bangladesh and Crédit Agricole Bank from France. They support social business through loans with interest or equity. The rest of the shares are owned by 3 private individuals, who have been with us more than 10 years and have always been there to support us. Our shareholders cannot use the dividends they earn for personal purposes, but must use them for society. That means the individual shareholders can actually choose to donate their dividends to our school.

When we do our business as a social enterprise, we are guided by our mission and shareholders, as well as Social Business Charter. In this Charter, there are 6 principles, 17 commitments, and 31 indicators. These help guide us very clearly on what to do to remain true to our social values. In every managers’ meeting, we always reaffirm our principle – that the livelihood of our artists is at our core. That is the only thing we are here for.

There are many forms in which social enterprise and non-profit organization can operate, but I have seen some organizations struggling with their identity and what they are driven by. In our case we are quite clear that we are a business and PPSA is the non-profit. We are a private limited company owned by shareholders, so we create wealth through our business, and at the same time contribute to our mission.

When it comes to making decisions, I have been very lucky to have very supportive board members. They listen well, even when I have to explain to them the evidence behind my decision. There are 7 of them, and 4 are from the school. None of them are primarily there for money, so when I propose something new or complicated to the board, I always ask myself, is this a business-driven choice, or is it socially-driven? That is my daily job, to always balance those two aspects.

I am glad Phare made the decision to bring in a leader with a different mindset, a business mindset, to the social enterprise from the very beginning. There were times when Phare tried to support graduates in conducting their own business in performing arts, but they did not work out because those students were artists, not business people. Once when performers tried to discuss a business deal with a hotel, both sides ended up getting angry, because they had different agendas and interests. My role here is to be in the middle, filtering the crazy ideas from the business people, and even crazier ideas from the artists, and finding a balance between what we can do, what we should do, and what we want to do. - Currently PPSE operates a broad range of businesses with circus, design, handcraft and event coordination. Do you plan to expand your business further?

- Every year we have graduates from PPS with many different creative skills. One of the immediate challenges we are facing today is how to provide enough opportunities and employment for these artists joining our group every year. It is both an opportunity and a challenge: it’s an opportunity because we have enough talent now to grow us to what we dream to be.

It is a challenging moment, but we reconsider our vision and identity every time we make a decision, and are careful not to keep adding on too much. New things may generate money, but they might not help us fulfill our commitment. We communicate internally and externally that our first mission is the livelihood of the artists, mostly from underprivileged backgrounds. The development of the artists, as well as staff members, is at the core of what do. Ultimately, it is not even about maintaining the school, if it does not help them live, because the school exists for their career development. So, whatever we do, if the new business does not synergize with our mission, and would steer us away from what we strongly believe, even if it makes money, I think we must be very careful with that direction. - Do you think this can be a new model in Cambodia? Lastly, can you tell us about your vision for the future?

- I imagine that even a company like Cirque du Soleil would have been in our shoes when they first started out in 1980s, but now they have become a global entertainment business that employs thousands of people. So where does Phare want to go from here? Shall Phare become a global Cambodian entertainment brand and employ thousands of artists? Or, will Phare continue to be a grassroots social organization that uses its talent for the wider social good? Both visions are equally possible, and we have not decided our direction yet. But one thing we are clear on is to keep Phare very open and welcoming. We are not trying to kill competition, but rather we want to help the industry be vibrant, interesting and competitive. The more choices there are, the longer tourists will spend in Cambodia, and ultimately if there is more employment, there will be better payment, benefiting the artists, and that’s what we want.

Someone advised us before that we should target tourists from China more. It is in fact a large and rapidly growing market: one company is currently building a theatre with 1,000 seats for a circus show with animals in Siem Reap, mostly targeting Chinese tourists, which is scheduled to open within 2017. The competition is suddenly real, not only for our business but also for our artists. It is a very scary time for us, of course, but it was also part of our vision to have a vibrant economy and various employers for artists, and it is happening right now.

Do I see Phare as a model for the future? I think this would be a very good model to study in about 5 to 10 years from now, to look at the impact we have brought about. In the near future, one could see if we have become a crazy moneymaking company or become an inspiration to guide people. In 10 years, we can see how the artists have evolved, how their lives have changed and how we survived.