The “Contemporary Theater Poster Collection, Preservation and Display Project” boasting a collection of over 10,000 posters

- What is the size of your poster collection now?

- I haven’t really counted it precisely but I believe I now have over 10,000 different posters in the collection of about 20,000 copies. And the collection continues to grow at a rate of about 500 posters a year. Since I get a lot of requests to borrow the posters I started a simple computer archive about ten years ago, which now has roughly 8,000 posters cataloged and of them about 1,000 are in data form for reproduction. Each poster is cataloged in this archive with the name of the [poster] designer, the name of the theater company, the play, the playwright, the main actors, the date of the play’s premiere and the theater name, and as reference an image of something like a flower or a woman that characterizes the poster’s design is added.

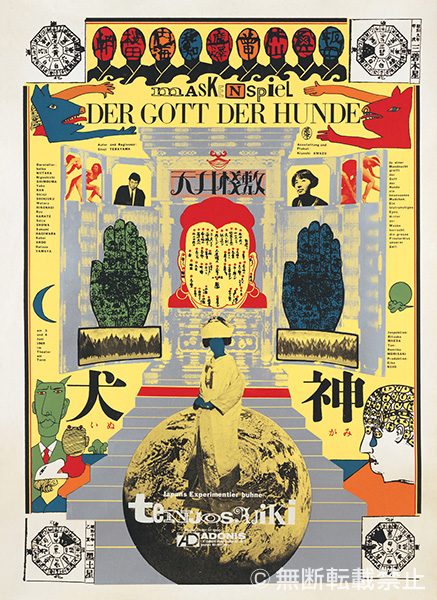

- And we are told that the important central part of the collection is theater posters from the angura (Underground) theater movement from 1960 into the ’80s, as represented by Shuji Terayama’s Tenjo Sajiki company and the Jokyo Gekijo company of Juro Kara.

-

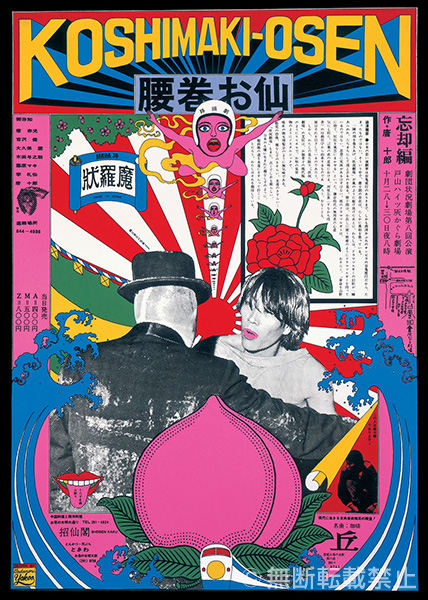

Yes, it is. Many

angura

posters, like Tadanori Yokoo’s famous

Koshimaki Osen Bokyaku-hen

(Jokyo Gekijo, 1966), which was acquired for the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art of New York (MoMA) in 1970, have been recognized for their exceptional artistic value. And as a genre within the history of Japanese poster art, they are recognized as revolutionary works that served as symbols of their era. In preparation for the holding of the World Design Exposition in Nagoya in 1989, a book titled

A History of Japanese Posters – POSTERS JAPAN 1800’s-1980’s

was published. It is a valuable poster collection that presents a broad overview of advertising art in Japan from the Edo Period, and one of its important chapters dealing with the posters of the

angura

era is titled “The Impact of the Underground.”

My collection includes almost all of the representative works of that era. Another substantial part of my collection that has not yet been shown publicly is posters like those for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics designed by members of the Japan Advertising Artists Club (*1) , like Yusaku Kamekura and Ikko Tanaka, who were the leaders of the postwar advertising industry. I have collected about 500 important posters by those designers. - By the way, are there any other collections of contemporary theater posters besides that of your project?

- In the area of angura theater posters, there is the collection of the library of Musashino Art University, where one of the leading designers of that era, Katsuhito Oyobe, is a professor. There is also a collection of contemporary theater posters in the Waseda University’s Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum. And the Toyama Prefectural Museum of Art also has a very substantial collection of commercial advertising posters.

- Would you tell us what led you to start the Contemporary Theater Poster collecting, Preservation and Display Project?

-

I currently run a business called Poster Hari’s Company that specializes in distributing theater, movie, concert and exhibition posters to restaurants, theaters, museums and other venues. I started this company back in 1987 out of the desire to elevate the status of poster distribution and hanging from the errand-running level job it used to be in the theater world of the day to a valid profession, where my company name could appear in the credits on the poster as part of the production and distribution staff.

That business put me in a position where a constant flow of posters from contemporary theater and other sources were coming into my possession. At the time I didn’t expect the company to last very long. I was thinking that it would be fine if I could continue the business for about ten years and maybe have an exhibition of the collected posters at the end. Also, since I was a child I have always been the type who couldn’t throw out paper things, so I began saving the leftover posters.

That eventually led to an offer in 1992 from a gallery in the Aoyama district of Tokyo to hold an exhibition, which was given the name “Super Poster Harister Collection” ( Hari being the Japanese for “hanging/putting up” of posters, etc.). Due to the fact that this exhibition was publicized as commemorating my 10th year in the poster distribution/hanging business and also the fact that it happened to come just at the time when the dissolution of the popular theater company Yume no Yuminsha had been announced, the newspapers and magazines picked up on the story and the exhibition ended up drawing a total audience of some 3,000 visitors. At that time there were public institutions that maintained collections of film posters at the Film Center and the Kawakita Memorial Film Foundation, but there was no such institution keeping contemporary theater posters. So, as someone who had begun a poster distribution business in the enthusiasm of youth, I felt a strong need to create a facility to preserve a poster collection, even though I didn’t have the financial means to do it myself.

As a first step, I announced to the people of the Shingeki (New Theater) scene that I would begin collection posters. I made it a practice from that time to collect the posters from each new play that was staged. I knew that there could eventually be a question of the copyrights for these posters, so I made plans to deal with that aspect as well. I theorized that posters were produced for the purpose of advertising and that the ones that should be collected and preserved were used posters that had actually been hung or posted on walls as advertisements. I thought that collecting used posters that would otherwise be discarded would minimize any problem of copyrights. So, I made a policy of collecting ones that had actually been hung in the theaters, and taking the pinholes or staple holes as proof that the posters had been used as advertisements. I also made it a policy that admission should not be charged at the exhibitions of these posters, and that when leased out for client use, the rate should be no more than the actual cost involved. And I also made a set of rules regarding use in commercial-base publications.

Regarding the angura era theater posters, I began to supplement my existing collection by personally purchasing or soliciting contributions of posters I didn’t have. Then I began organizing exhibitions at various venues.

Since preservation requires money and the project had already grown beyond what I could handle privately, I was fortunate to receive a grant from the Saison Foundation (3 million JPY [approx. 3300 USD] over 3 years) and took that as the opportunity to formally establish my “Contemporary Theater Poster Collection, Preservation and Display Project” in 1994. The principle for the project was “collection, preservation and exhibiting of theater posters from around the world” and the principle I had already adopted for my Poster Hari’s Company: “Stimulating the theater world through advertising art.” - You are also cooperating in the poster-collecting project started by Tokyo’s New National Theatre.

-

When the New National Theater opened in 1996, they came to me saying that they wanted to collect an archive of materials related to contemporary theater for their affiliated Information Center, and from 1998 we started a joint poster preservation and exhibiting project. This is a project limited to collecting new poster works with the assistance of roughly 2,000 theaters companies and theaters around the country, from which 500 posters are chosen for the collection every year and a book published featuring 80 of those.

I had long thought that poster-collecting should be done by a public institution, so I was glad when a national institution like the New National Theatre, Tokyo began this poster-collecting project. There is now a collection of about 5,000 posters in the Theatre’s storeroom. Until now there have been so few opportunities for poster designers to come to the attention of the public, so it appears that this project is providing new encouragement for them as well. And, I believe that this is another activity that can contribute to “Stimulating the theater world through advertising art.” However, with recent changes in personnel and the organization at the Theatre, the project seems to have lost some of its original initiative and it is apparently getting more difficult to secure the necessary funding. I hope they will somehow be able to continue the project.

Although I started collecting posters at the age of 30 with little more than a vague intent and not knowing anything about what it involved, after doing it for a couple of years I felt I had started something I would have to continue for as long as the art of theater lasted. And now, as of April of 2009, I am running the Shuji Terayama Memorial Museum in Misawa (*2) with Terayama’s former wife and producer of Tenjo Sajiki, Kyoko Kujo. So I have ended up carrying two crosses I can’t put down, one in contemporary theater posters and the other in Shuji Terayama.

A fateful encounter with Shuji Terayama leads to poster collecting

- Would you tell us how did you first become involved with theater?

-

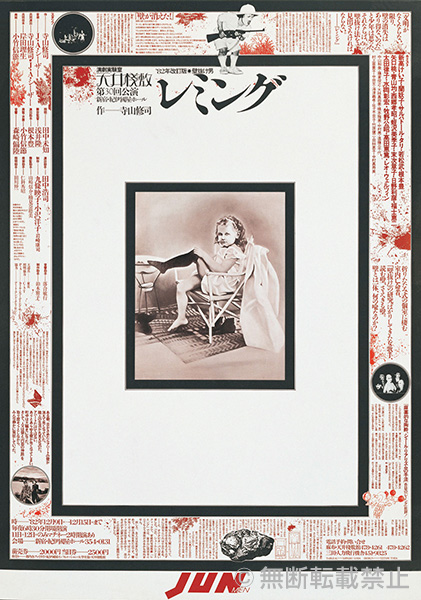

It was back in 1982 when I was 19. I discovered the small-theater scene that was booming at the time. The first play I saw was one by Hideki Noda ’s Yume no Yuminsha and the third play I saw was the Tenjo Sajiki production of

The Lemmings

at the Kinokuniya Hall that would be Shuji Terayama’s last work. It was a time in my life when I had dropped out of college and was in a state of moratorium, and the words of Terayama’s play struck me to the soul. I felt that I had finally found what I had been looking for and it changed my life. And that encounter with Tenjo Sajiki was also my encounter with the posters of the

angura

theater movement.

I wanted to become a member of Tenjo Sajiki but Terayama died on May 4th of the following year and the company was disbanded. At that time they had a bazaar to sell off the company’s props and posters and such, and as a fan I went and came away with a large thermometer prop that had been used in The Lemmings . When I was 20, my parents cut me off financially when I told them that I was going to make my living in the theater world, so I was really hard up for money. But I was blessed with friends who liked the theater and thanks to their graces I was still able to see about ten plays a month. Wherever I went at that time I would meet Ms. Kujo. It seemed at times as if I was chasing after her.

One day at a performance of So Kitamura’s Junin no Shonen she happened to be sitting in the seat next to me. She asked me if I wanted to work in the theater since I seemed to love it so much, and she gave me her business card. Thinking that this was a once-in-a-lifetime chance, I contacted her. She gave me a job on the staff of the second of the series of Shuji Terayama Memorial productions at the Seibu Theater, (present PARCO Theater), Aomori-Ken no Semushi Otoko (The Hunchback of Aomori: ’83). That would be my first experience with distributing and hanging theater posters. That led to be being hired part-time to put up posters for Seibu Theater, which started me on the course to the work I do now. While doing that job, I also took part in the Terayama-related productions of Jinriki Hikosha that Ms. Kujo was producing, working as a stage hand and eventually as assistant to the director for the Terayama memorial productions. And the staff that worked with me when I was put in charge of organizing the “Shuji Terayama Complete Film Exhibition” in 1985 are the people who joined me when I established my Poster Hari’s Company. - What activities have you engaged in since holding your own first poster exhibition in 1992?

-

Thinking that posters could be used to help present an overall picture of contemporary theater, I held a series of exhibitions in Vienna, Prague and Budapest in 1996 with support from the Japan Foundation. Then in Tokyo I organized a “Contemporary Theater Poster Exhibition ’66/’96 – Provocative Posters Paint the Town in Contemporary Theater” as a large-scale exhibition showing 500 contemporary theater posters spanning a 30-year period. The newspapers caught onto this exhibit and it ended up having a draw of about 10,000 visitors. This exhibition brought a change in the way our project was viewed and theater companies began to come forward and ask us to keep their posters and people like silkscreen printers with personal collections of posters began to donate their collections to us in hopes that we could put them to good use.

In 2004 I organized an exhibition titled Japan Avant-garde – 100 masterpieces of Angura Theater Posters , as a selection of 100 of the best posters of the Underground theater movement from the 1960s into the ’80s. For this exhibition I chose many of the most interesting posters from Tenjo Sajiki, Jokyo Gekijo, Black Tent Theater and the butoh of Tatsumi Hijikata, and all of the posters were included in the show’s catalog, which was printed by PARCO Publications as a definitive collector’s item (364mm×515mm size). After an exhibition at the Logos Gallery to commemorate the publication of this book, we exhibited the posters simultaneously at a large number of Golden Town restaurants and bars where the angura posters used to be posted in their day. The editing of the book was quite a task due to the factions within the angura movement and their belief in an avant-garde spirit of never looking back. But, I think it succeeded because of the timing and because of the fact that I was a “third person” who had never belonged to any of the companies of that era. I don’t think it would have been possible if I had ever been a member of Tenjo Sajiki, for example.

We have also done an ongoing series of exhibitions in the lobby of the Setagaya Public Theater at a rate of three or four exhibitions a year rotating their permanent collection ever since the theater’s opening. And, when we receive requests, we lend out posters at rates that just cover the basic costs. These leases include posters for the sets of films and television, and we organize poster exhibitions to accompany overseas performance tours and exhibitions for theater lobbies. In all, these request amount to leases of about 100 posters each year. - One of the revolutionary large-scale contemporary theater poster exhibitions was surely the Contemporary Theater Art Work 60’s to 80’s Exhibition” held in 1988 at the Seibu Museum of Art (name changed to Saison Museum of Art in 1989 and closed in 1999). Were you involved in this exhibition?

- I had already started out Poster Hari’s Company at the time, so we were involved in putting up posters for the exhibition and distributing leaflets, but I wasn’t involved in its planning. That exhibition arose from the suggestion of an Osaka editor named Jun Kobori. One of the characteristics of the Underground theater posters of the day was that they were mostly printed by the silkscreen method. Instead of a woodblock or board, this method used stencils on fine-weave silk to make multi-color prints that were hand printed one by one. I hear that Kobori proposed the exhibition after reading an essay about the appeal of silkscreen posters by one of the leading graphic designers at the time, Katsuhito Oyobe. The resulting exhibition was a revolutionary one that gave a broad overview of the theater posters from the angura era into the era of the popular small-theater companies of the 1980s.

- In 2009 you opened your Poster Hari’s Gallery in a converted apartment in the Shibuya district of Tokyo.

-

When I first launched my poster collecting, preservation and exhibiting project, I actually envisioned something like a poster art museum, as a place where people could go to see a full collection of Japanese theater posters and there would also be information about posters from around the world. I know that isn’t possible for me, but at least I wanted to open this gallery as a place where today’s young people, who are used to experiencing things only on their computer screens, could have the opportunity to see the actual works. For now, my plan is to present a series of exhibits focusing on the individual artists about twice a year from my collection of posters from the 1960s. In addition, I want to organize a variety of live events.

The reason that I call the posters of the Underground era “Japan Avant-garde,” as a nod to the “Russian Avant-garde” period of art history, is that I want to communicate to today’s designers the fact that it was an era that had a distinct form of artistic expression. I feel that one of my missions should be to communicate to today’s designers that they should have a knowledge of this era as one of the foundations against which they can work today.

Angura theater posters as an insurrection by young designers

- Underground ( angura ) theater posters can be seen as one of the great achievements of Japanese contemporary theater. The people who did the graphic designs for these posters included a star-studded list of artists such as Tadanori Yokoo, Kiyoshi Awazu, Genpei Akasegawa, Akira Uno, Kuniyoshi Kaneko, Katsuyuki Shinohara, Katsuhito Oyobe, Koga Hirano, Yosuke Inoue, Masamichi Oikawa, Ryoichi Enomonto, Kazuichi Hanawa, Seiichi Hayashi, Sawako Goda, Tsutomu Toda and Shiro Tatsumi. And the posters they designed were not simply a medium to announce the holding of a play but a medium for innovative graphic artistic expression as well as an embodiment of the message involved in the play that the audience was about to see.

-

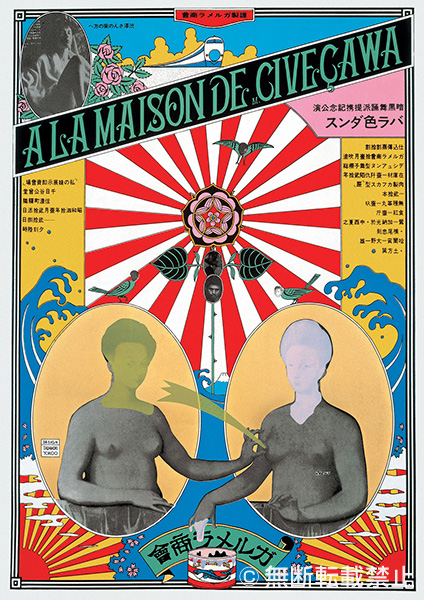

The poster that sparked the

angura

theater poster genre probably more than any other was the poster for Tatsumi Hijikata’s Ankoku Butoh-ha Garumega Shokai company’s

Barairo Dance – A LA MAISON DE M.CIVECAWA

(1965), which was a psychedelic poster making abundant use of florescent colors. At first, Hijikata had asked Ikko Tanaka to do the poster for this production, but Tanaka said there was an interesting designer and introduced Hijikata to Yokoo. When Juro Kara saw the resulting Yokoo poster, he asked Yokoo to design the posters for his Jokyo Gekijo. The first product of that union was Yokoo’s now famous

Koshimaki Osen Bokyaku-hen

poster. It was truly a shocking work. When you look closely at Yokoo’s work from that period you will see an apology “Forgive me for being late” actually printed in small letters on the posters. We are told that this is because the printing was always behind schedule, and sometimes the posters didn’t arrive from Yokoo until the day of a play’s opening performance.

The angura theater posters of the day were strongly influenced by the American hippie culture. In 1968 a poster shop opened next to the Hanazono Shrine in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo. That shop had posters by people like graphic designer Peter Max, the leader of America’s psychedelic art movement, and that surely had a big impact on designers of the day. The year 1968 was a historically important one that saw student rebellions erupt around the world, and in Japan it was the year that the student activist group Zenkyoto barricaded themselves in universities and fought violent encounters with riot police. The Underground theater movement was also related to these social/political events of the period, and that rebellious spirit spread to the world of graphic design as well. To them, posters were not a medium for advertising but a medium for self-expression and the trend was to use posters for communicating the message of their generation.

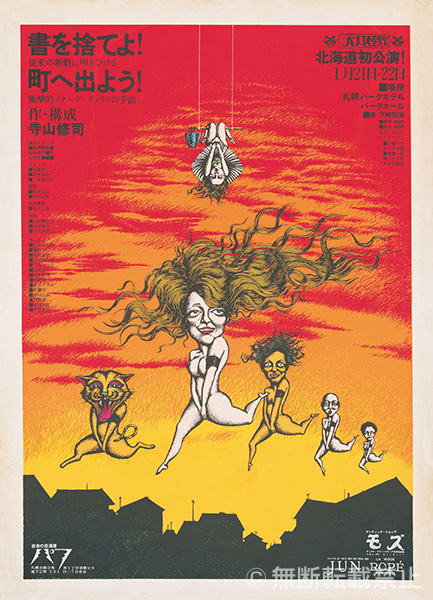

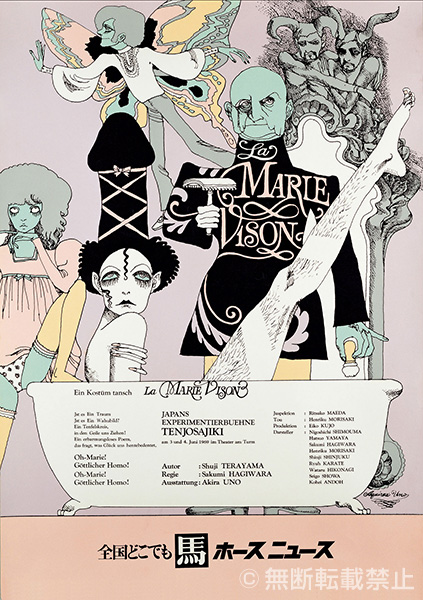

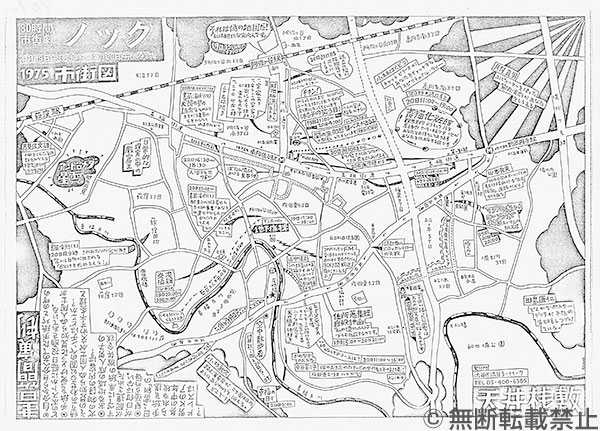

The definitive work that sparked the new movement in poster design was certainly Yokoo’s Koshimaki Osen Bokyaku-hen poster. It showed young designers just how much could be done in a poster and that anything goes in poster design. That was a big stimulus for a group of designers and young artists associated with the other talents gathered in the Underground theater movement and linked together by a sort of gravitational pull, and the result was a rush of creativity that saw the designer competing with each other to produce ever more revolutionary and controversial posters. In the midst of this movement the 68/71 Black Tent company declared that their posters were a form of “wall-hung theater.” At the same time, Tenjo Sajiki advertised their plays with a series of what they called “time posters” that were hung around town. In this way, the posters themselves became a form of theater.

The Tenjo Sajiki posters were designed by Yokoo, Awazu, Ono, Oyobe and Tatsumi, while the Jokyo Gekijo posters were designed by Yokoo, Shinohara, Akasegawa, Goda and Kaneko. With the exception of Awazu, all of these artists were young, in their early 30s (born in 1935-36). By the way, the previous generation of designers, the first postwar generation, were the ones who formed the Japan Advertising Artists Club and created their own design revolution, including Tanaka, Kamekura, Tsunehisa Kimura, Shigeo Fukuda and Kazumasa Nagai, etc. The public exhibitions of the Japan Advertising Artists Club had served as a gateway to recognition for young artists, but it would become a target of student activities in the late ’60s as an authoritarian institution. This led to the Club’s dissolution in 1970. Then it was the Yokoo generation of independent designers who emerged in to fill the gap. - Thinking about it, your Poster Hari’s Company principle of “Stimulating the theater world through advertising art” seems to be an attempt to recreate the spirit by which posters were once considered a form of theater in themselves, isn’t it? I see now why, in Terayama’s words, it was possible to “do street theater with posters.” Also, a name that is often heard as a printing company that supported the young designers of that time is Saito Process.

-

Saito Process was a small printing shop that had silkscreen print technicians, and young designers would often go there to have small editions of ten posters or so printed to submit to the Japan Advertising Artists Club contests. In that way it helped support the activities of the young independent designers. Saito Process no longer exists, but when the company was dissolved the entire collection of posters it had in storage was donated to The Musashino Art University, and that is why the university’s art library has such a great collection of posters of that era.

Silkscreen is a form of printmaking that can be done at home, so there is not really a need to take the printing work to a printing company. The Jokyo Gekijo and Tenjo Sajiki posters were printed at Saito Process, but the posters for Mitsuhiro Kushida’s Jiyu Gekijo were printed by himself in his own home. That’s why they are in the A full-sheet size and you can see the marks left by the clothespins used to hang the posters when drying the ink after printing. Silkscreen printing is a craft but it is also a medium of expression that enabled young designers to work freely and print their own posters by hand without spending money to hire a printer. This made silkscreen popular as a potent weapon for young artists. - In the 1980s, there was a shift in the theater world away from the controversial angura theater that challenged the social establishment toward the small-theater plays that became popular among young people. The posters for the plays of Kohei Tsuka that became the hot thing of the time were designed by the illustrator Makoto Wada.

-

Wada was also born in 1936 and had already been active as an illustrator, but his work was not suited to the Underground theater movement. It wasn’t until Tsuka’s small-theater works became popular that Wada made his appearance on the theater poster scene. The posters were not designed for the B full-sheet size but smaller, and you no longer saw the

angura

style “wall-hung theater” poster movement being used. There are also other illustrators after Wada who became associated with theater companies, such as Yukio Kawasaki, Michio Hisauchi, Suehiro Maruo, Fumiko Takano and Yoshifumi Hasegawa. But the decisive difference between them and the graphic designers who did the

angura

theater posters of the 1960s is that most of the

angura

poster designers were also doing the stage art for the productions they created posters for. I imagine it was probably the case that they were asked to do the stage art and designing the poster was one part of that job. That’s another reason why the posters were also a form of theater. However, when you get into the 1980s, the posters were ordered separately. What’s more, there was now a division of labor in which the designer who designed the poster and the illustrator who did the illustration for it were also two different artists. This made a big difference in the nature of the posters as a medium of expression.

In addition, recently theater posters and leaflets have become things that are evaluated simply in economic terms for their cost performance. When thought of as tools for selling tickets, it becomes a question of how many tickets will be sold by printing and distributing 100 posters, which may lead to the decision that there is no need to do a poster because of its poor cost performance. It can also lead to the decision to use the same design for the poster and leaflet in order to avoid an added cost. That is the kind of commodity the poster has become.

In recent years, theater productions are no longer created by theater companies, but instead by “units” and production agents, which means the loss of the former aspect as a communal project by a large group of theater people constituting the theater company. This is one of the reasons why there is no longer a need for the type of “Japan Avant-garde” posters of the past that stood as banners of the theater companies. Nonetheless, leaflets and posters remain an expressive medium that has the potential to motivate the people involved in a work of theater and to communicate a message to the people who see them. Depending on the expressive quality of the leaflet or poster, it can also be a driving force behind a work. It is a medium with the potential for substantial artistic expression. That is why it is sad to see this medium discarded so easily. - From what period did this trend become prominent?

-

One big influence, I believe, came when the popular theater company Otona Keikaku stopped using posters. Another change came when leaflets as inserts came into use by the small-theater companies, which reduced printing costs and allowed the companies to just print large volumes of leaflets and just leave their distribution up to others without thinking about the results. I believe this is another trend that led to the decline in quality and expressive content of leaflets and posters. At the same time, computers made it possible for designers to work without having to be concerned about the final result on paper. They could just hand over the design data to the company in digital file form and often not even check the quality of the printed colors. My honest feeling is that I want to ask these designers if it is really OK with them when the final printed product doesn’t have the color expression they intended.

The advances in IT are a fact and it is certainly nice to have the options IT offers, but I have my doubts about letting everything just be swept in that direction. If people decide that the internet is better everything will be swept in the direction, but if we don’t try to maintain a society where the internet and paper media coexist, the quality of expression is certain to decline. What do you see as the recent trends in posters as an expressive medium?- With the predominance of theater being produced by production companies since the 1990s, we see mostly posters and leaflets that are nothing more than group photos of the actors in the production. It become a question of how much audience a given actor can draw, and the agencies with high-draw actors become more powerful, so the work of the designer becomes little more than taking group photos. And, since it simply becomes a question of how the photos are used on the poster or leaflet, they designs become quite boring in terms of artistic expression. Since 2000, almost all the leaflets and posters use only photographs. I believe that the graphic designers must have gone through a period of trial and error. But, although using photographs has become a must since 2000, a few designers have emerged who produce designs that use the photographs to achieve something beyond the mere name value of famous actors and create posters with expressive impact that approaches that of the actual theater work. People like Shinichi Kono, Satoshi Machiguchi of Match and Company and Gaku Azuma are designers who do good work. So there are some hopes left in the profession.

- Are there any companies today that are still producing art posters like in the Japan Avant-garde era?

- In Tokyo, companies like Juro Kara’s Karagumi and Akaji Maro ’s Dairakudakan still produce B full-sheet size posters like in the past. In Osaka, Ishinha doesn’t produce many posters , but they do produce good leaflets. Their advertising art since 1997 has been handled by the manga artist and graphic designer Gaku Azuma, who produces outstanding work. Although this is my personal judgment, I believe that directors who don’t write their own plays tend to be not as concerned about advertising art. This was also true in the Underground theater era, which is why you saw good posters for the productions of Terayama, Juro Kara and Makoto Sato.

- Despite the fact that so many posters with high levels of artistic expression were produced in the 1960s and often won high acclaim as art, did it actually change the position of posters in society and the appraisal of them as a medium for expression?

- No, it didn’t. That is something I would like to change. But, in today’s world economic effect takes precedent over everything. It doesn’t need to be that way, and I would like to help restore the possibility that seeing a single poster or a single leaflet can produce an encounter with theater and maybe change a person’s life. Perhaps I say this because I am a person whose life was changed by an encounter with theater.

- What can be done to help restore the poster as theater?

- One thing is to change the consciousness of the people who create them. In the present state, where the poster and leaflets and the poster hanging are all left up to outsiders and the job is broken up into increasingly more detailed division of labor, the sense of working together with people to create something of value is being lost. When small-theater companies come to Poster Hari’s Company to use our poster-hanging service, we tell them that it is best if everyone gets out on the streets together to put up the posters around town as a communal job, and in the past I even used to turn down jobs for that reason.

Shuji Terayama used to talk about “systemizing the randomness of encounters,” and in fact we are all supported by people we have met by chance. And I believe that, in fact, posters and theater are both means of “systemizing the randomness of encounters.” The Stenberg Brothers who were famous poster artists of the Russian Avant-Garde said: “Posters offered unlimited chances to experiment with possibilities of artistic expression. We tried every means we could imagine to complete a poster that would make people on the street stop and look.” I wish that people today involved in creating works of theater and graphic designers would take these words to heart.

I don’t know whether all of the designers involved in theater poster creation and posting back in the 1960s had that spirit. I know that many of them thought that poster-hanging was a bother, and I imagine there were some who just left their assignment of poster lying in their rooms undistributed and unhung (laughs).