Thoughts about Echigo-Tsumari and its Meaning

-

At last the 4th holding of your festival, Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennal 2009, is about to begin. I have been covering the festival each time from its first holding and I am amazed to see the changes the Echigo-Tsumari area has undergone during this time. For the first festival you had the young supporters of the “Kohebi-Tai” group coming into the area suddenly and having to begin by explaining to the elderly men and women in the community asking what contemporary art is. It was before the main facilities were ready, so they had to pitch tents on the planned construction site and begin creating their installations, while other supporters laid out rented futon bedding to stay in the gymnasiums of closed schools.

By the second holding (2003) the main facilities and the local people were joining in with the artists in the work and sweat of creating art works and it thrilled me to see what felt like the reawakening of deep-seated, primal strength. In the meantime this area was struck by a devastating earthquake and torrential rains that damaged the land seriously. When that happened, the people who had build relationships with the community here through their involvement in the festival came to help in the recovery and continue participating in the community events throughout the year.

Then by the time of the third holding began the full-fledged efforts to turn the deserted homes and closed schools of the area that are now the festival’s symbols into art spaces and artworks in themselves. Now Echigo-Tsumari has entered a new stage as a veritable art village. In just ten years time so many people have become involved in this depopulated region and its aging population. I think that is a truly amazing achievement. (Refer to the notes for a history of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennal). -

Echigo-Tsumari is a region that is buried in deep snows in the winter and hot in the summer. There is no flat land at all, so its people have long had to use their ingenuity and make tremendous efforts to build terraced rice paddies on the slopes and straiten the streams in the hills in order to get narrow strips of land along their banks where they could make rice paddies in order to seek out a living as farmers. But from about 30 years ago, Japan became possessed with an extreme mentality of “efficiency first.” And they began to say that farming up their in the hills is inefficient and living in a place where you have to dig yourself out of the snow all winter is inefficient and encouraging people to leave that life. The government essentially told them that they would pay these people to give up growing rice in the hills and that they would give them money to move to the cities.

The villages you have there today inherit a unique way of life that their ancestors carried on for generations and the way they have spent their time is also unique, so who has the right to decide that their lives are inefficient? It is natural and necessary that they live there and it is unthinkable that anyone should assume to tell them that they shouldn’t live there. That’s why I wanted to find a way to tell them that the lives they had lived there were a part of an important heritage. Art has the ability to show history and lives in ways that are very clear and understandable, so I believed that it could be useful in helping people rediscover the vale of their region.

However, I have never had any intention of trying to do anything about the agriculture of the problems of the natural environment there. Getting involved in political matters can only put you on tenuous footing, and art doesn’t have that kind of power in the first place. What I was thinking is that if the elderly men and women there want to die in the place where they have lived their lives, I would like to support that desire and help make their days as enjoyable as possible until that day comes if I can. And I also thought that this is important for the region to be revitalized. I thought that I would like to take the outlook of considering what kind of give-and-take between the region and the urban centers could help this region survive.

Art is close to the body, the senses and our sensitivities and it has been effective in giving us an intuitive sense of the distance between the human being and nature and between one human being and another. And it is also a true manifestation of the fact that all human beings are unique individuals. If we can’t make that power of art effective there in Echigo-Tsumari, we would have to ask ourselves once again what art really is and should be. As someone who has been involved in art, I thought that returning to those basics of the human body and human nature and see what we could discover there in Echigo-Tsumari could also bring new hope to art and its role in society. That is the point of departure of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennal.

After the Meiji Restoration (1867) the Japanese government began removing from the framework of art all the things we had enjoyed as part of our lives that could not be controlled, displayed or catalogued, such as festivals, culinary culture, gardens and the tokonoma alcove of the home where we displayed things seasonally. That is something that has led to an impoverishment of contemporary art. At Echigo-Tsumari we put all of those things to work as spreading wings of motion. I wanted to use them to delve into the questions of how human beings interacted with water, how they became familiar with the soil, learned hand skills, built awareness, culture and art. I thought that if we could retrace that route humankind has come once again, it could provide important clues [to how we should live now in these times]. - There was a lot of opposition at first.

-

The opposition was daunting. They said using public funds for art was unthinkable. They asked what use art could possibly be in such a rural area. In the space of four and a half years we held 2,000 meetings to explain our purposes to different groups. Despite those efforts it wasn’t until June 15th that authorization was finally received for the July 25th opening of the first festival. We had gone on with the preparations determined to go ahead even if public funding was not received, but it was indeed a hard fight.

Since we are basically setting out to build things on other people’s land, it is natural that there would be aversion. In the dialogue to try to overcome that, the artists were able to communicate their feelings of respect for the elderly of the community, telling them that their lives and all the hard work they had done to live on this land were proud accomplishments. In response, when the local elderly saw the supporters and the artists struggling in their tasks, they began to join in and lend a hand. They are farmers with a variety of useful skills, so they are good at working with their hands. And if they help out, it gradually becomes their project too. They were glad to have outsiders come to their village and they began to talk about the art works, and then about their land and about their families.

You could say that art is like a baby, it doesn’t do any work and it takes a lot of care. But in the process of nurturing and protecting it, communication becomes established. It’s like people from outside coming in to help re-create the festivals that depopulation had caused to die out. It took a lot of energy to overcome the initial aversions, but I believe that energy has eventually invigorated the region.

Looking back, I believe it is extremely important that, rather than working with people who understood and agreed with us from the beginning, the process of overcoming barriers built true “cooperation” between the artists, the local villagers and the supporters. And I believe that the preconceptions about the role of the public sector have begun to change in Echigo-Tsumari. Among the “supporter” were many art university students making up the Kohebi-Tai that went to Echigo-Tsumari from Tokyo. Based on the records, there were about 9,440 people in all (800 registered).

From the beginning it was my intention to work with young people and I thought that having these young urbanites, who were so completely opposite in background from the elderly people who had been farming there in the hills of Echigo-Tsumari all their lives, would actually help things get moving more easily. For that reason I wanted to bring these young people, who were involved in these strange activities called art, and place them at the forefront. Again it is like the analogy with the baby. Because these two groups of people were so completely opposite in terms of experience, there were inevitably some collisions at first, but having in front of them these “babies” in the form of art works in the making, gave them a common goal that helped get them over their differences. Being different types of people from the beginning also made it easier for the two groups to voice their differences and complain when they needed to, but we found that once the young people came into the rural community they “do like the Romans when in Rome” and that became a point of connection that helped everyone create things together. Thus, they achieved things that I believe would not have been possible were it two groups that were more similar in nature from the beginning.

By the way, at Echigo-Tsumari it became natural for these unknown young people to assume roles like moderators at meetings attended by the prefectural governor or senate representatives simply because they were members of the “Kohebi” group. The name “Kohebi” virtually gave them a free pass to go anywhere and go anything for the projects. Because they were there as supporters, they were welcomed. In time we even found local merchants beginning to target business efforts at them [laughs]. - Ten years ago it was rare for students to do fieldwork like this, but today students are almost always an important component of art projects everywhere. Universities today have opened themselves up more to the communities and are aiming to incorporate practical learning experiences within the society, and regions faced with the issues of depopulation and aging populations have come to look to student groups as a vital source of energy. In the Chiba New Town community, you have linked about 40 seminars and the like in a project you call “Art Universidad.”

-

Professors say that their students who have experienced participation in Kohebi projects gain a much clearer sense of purpose. The reason is that they are working with adults. From the 3rd Echigo-Tsumari festival we had adult supporters we called the Oohebi (oohebi = big snake, kohebi = baby snake) who would come to Echigo-Tsumari on the weekends when they didn’t have work and they would work together late into the night with the young Kohebi groups and teach them new skills. This is the true form of education. Lately we have supporters coming from overseas as well, for example, we have a group of 30 students coming from Hong Kong University for three weeks.

Even for people whose feet are firmly planted in the locality, art opens up a window to the world and international consciousness is born naturally. That is an interesting aspect that comes into play when art is involved. - Your efforts with the vacated house and closed school projects have produced especially important results.

-

Now we are in an age when the focus is no longer on making new things. However, there are still many buildings that can useful in the true meaning of the word. It is a process of making use of existing things to produce new value. We also took advantage of the fact that the big 2004 earthquake left a lot of newly vacated homes in the area. When you seen an abandoned home it is truly like a light has gone out. And having a school closed down is even a more disheartening thing for a community. So I wondered if there wasn’t something we could do about them.

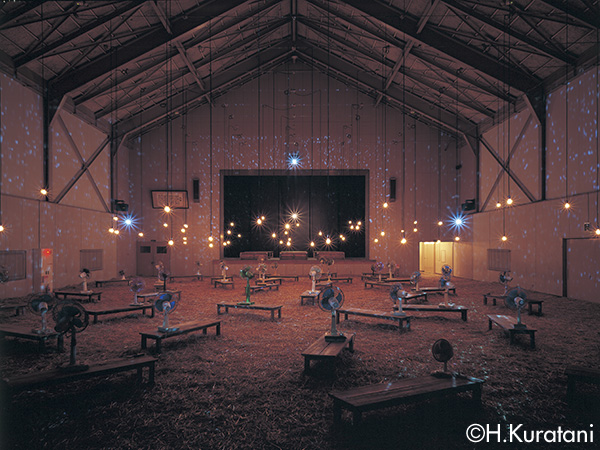

With the Echigo-Tsumari festival, our artists focused particularly on “place” and made efforts to bring alive the temporal qualities of the places they worked with. Probably the most definitive of these works was the work led by Yoshio Kitayama for the 2000 festival using the old Kiyotsukyo Elementary School Tsuchikura Branch School. In this work Kitayama gave form to temporal involved in voices of children, their play and the feelings of the local people watching them. It was very clear to me that this was the kind of work the artists were doing at Echigo-Tsumari.

For the 4th festival [this year] we have artists including Antony Gormley, Claude Leveque and Chiharu Shiota working hard on empty house projects. In the case of vacated houses like these they are still the private property of someone, so we can’t use public funds on them. We have to buy the properties in order to use them in our projects and then we have to get back our investment by finding someone sympathetic with our project who will buy the property. We are still looking for prospective owners for some houses. So, if anyone is interested, please contact us [laughs].

For this year’s festival, it is the closed schools that are the most important focus of our program. We are going to renew all 13 of the remaining closed schools in the area. We still only have long-term projects begun for about half of them, but eventually we plan to get the assistance of the people in the local communities and revive all of these school facilities as permanent spaces.

In the 2006 festival, Christian Boltanski teamed with Jean Kalman to create a permanent work using the old Higashikawa Elementary School, and this year new aspects will be added to it. Next year, as a project on the island of Teshima in the Seto Inland Sea, Boltanski will create a new project employing the sound of heartbeats that have been recorded all over the world, and his Higashikawa Elementary School site is one of the places that the heartbeats will be recorded. As other new developments this time, Seizo Tashima will work with the people of the Hachi community to create a “Museum of Picture Book Art” and there will be an installation by concert pianist Tomoko Mukaiyama using 10,000 pieces of silk clothing at the old Tobitari Daini Elementary School. Also, Tadashi Kawamata will create an archive of projects where art is used for community renewal/development called “Inter-local Art Network Center” at the old Shimizu Elementary School. There are also many universities involved in the Echigo-Tsumari festival, and this year Kyoto Seika University will be joining us for the first time with a long-term project dedicated to development of hill country village communities using the closed school at Karekimata.

Also, there is a crisis right now confronting the Matsunoyama Branch School of the Niigata Prefectural Yasuzuka High School. If they don’t get a quota of 30 students registered to enter the school, it is going to be closed down permanently. There is no time to waste, it is a do or die situation. So, we got the idea that if we all registered to enter as high school students, we could support the school and keep it alive. It’s an interesting proposition, isn’t it? It would create a connection with the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial and our Kohebi and Oohebi members could all become high school students [laughs]. We are now in the midst of concerted negotiations. Since reaching its peak in 2004, the population of Japan is now decreasing. The population in the cities continues to grow, so there are concerns that the depopulation of the regional areas is going to accelerate at an even faster rate. Are there things that you have learned from your activities in Echigo-Tsumari about new ways to deal with these issues?

One is a way to help the elderly farmers of the region continue to work their terraced rice paddies by having people become terraced paddy owners. The number of people who have become members of this owners program and the fan club both is now around 500. To support Echigo-Tsumari it is essential to have support groups from the urban areas providing both personnel and financial support, and what has surprised me most is the fact that the people in the cities are searching for places like Echigo-Tsumari that they can become involved in even more than the rural communities are searching for supporters. Some corporations have already recognized this trend. The travel agency JTB is one, and they have launched a business serving as mediators for people from the cities who want to move to rural communities. They are now cooperating fully with us in Echigo-Tsumari and they have planned advertising and tours for us.

It costs at least 300,000 yen a month to live in Tokyo, but in a place like Echigo-Tsumari you can live on 100,000 a month, which means that it can be possible to enjoy a more affluent lifestyle there in the country. The number of people thinking this way is on the rise. I believe this is a big tectonic shift. But usually you have to have children in order to enter a new community. In Echigo-Tsumari, however, an involvement in art can be your key to becoming a part of the local community. This is a defining difference. Art can be your ticket of entrance in Echigo-Tsumari.

Learning from Gaudi about concern for regional communities

- When you involve yourself with a regional art project, you begin by doing a tremendous amount of research into the region and then you always initiate art projects that reflect that knowledge. For example, before starting the vacant house projects, you brought in architectural experts and surveyed the houses of the area. And for you project involving Niigata’s Shinano River you had a survey done on the flow dynamics of the river and you also had the artist Yukihisa Isobe, known for his works involving tracing on the land, do a project.

- I don’t know if you can really call it survey as such, but I always travel personally all around the region I am dealing with. In the case of Echigo-Tsumari, I put 12,000 km on my car’s odometer driving all over the region before the start of the first festival there in 2000. But nothing interesting will come of trying to use the knowledge acquired that way for the edification of the community.

- Your involvement with regional communities didn’t begin with Echigo-Tsumari. It seems to be something that goes back to the fact that you were raised in Niigata and your early involvement in student demonstrations and such. Just looking at your activities as an art director, you were producing exhibitions involving regional venues from early on, such as organizing the first exhibition to introduce the works of Antonio Gaudi in Japan in 1978, which toured to 11 venues, a “Print Exhibition for Children” that traveled too elementary and middle schools around Japan (1980), and he produced the “Apartheid NON! International Art Exhibition” (1988) that toured to 194 venues around Japan.

-

My original point of departure was actually a much narrower one. Put simply, I was wondering why there was so little interesting work going on in Japanese art. It was an art scene dominated by a very limited number of people and it was not supported by the public at all. Given that situation, I decided that, rather than becoming an artist and seeking my own form of expression, I could perhaps do more working behind the scenes to direct artistic activities. And that is what I have been doing ever since. I believe that the place where you can bring out the problems and issues involved in art most clearly is in the regional communities with their clearly defined interpersonal relationships. I still basically only believe in arts and culture that are born from selling tickets one by one, not arts and culture that have been “authorized” by some authority. I believe that is the basis of regional arts and culture and only within that context can things really be seen for what they are.

Concerning regional culture, I believe I learned more from my study of Gaudi than anywhere else. Gaudi’s works exist very naturally in Barcelona and they fit in very well with the surroundings of the place. It is also natural that Gaudi didn’t leave many architectural blueprints, because his working process was one of give and take with the artisans [stonemasons, carpenters, etc.] and involved starting out with a 1/200 scale model, then a 1/50 and a 1/20 and then finally a 1/1 that was the actual building. Therefore, when I think about Gaudi, I think in terms of the world of those “Gaudis” and the primal experience of things being born in that world.

Gaudi was still in his 20s when he represented Spain at the Paris World Exposition. He was Spain’s rising star. At the time, Gaudi was supported by local weaving industry that had risen with the industrial revolution and the churches of Catalonia, but they were frail entities. His patron, Eusebi Gu¨ell and others in the weaving industry were interested in building a utopia in lines with early socialist thought. But that dream was crushed by the first Great Depression. The churches of Catalonia was eventually suppressed by the central government and rendered ineffective. With the loss of these backers, Gaudi was finally left with only his Sagrada Familia.

The interesting thing about the Sagrada Familia building is that its creation began with collecting materials from dismantled buildings. Although it is different now, in Gaudi’s day it was built by deciding what stones went well with what other stones. This process led to rough and unsophisticated sense of material. The origins of Gaudi’s art went back to the chorus association he was a member of in his youth and the association of exploration in Catalonia. The chorus association was an underground organization that sang in Catalonian, which was outlawed by the Spanish government at the time. In terms of a Japanese equivalent Catalonia’s association was something like the Rojokansatsu Gakkai (ROJO: Unknown Japanese Architecture and Cities or Street Observation Conference) formed by architect Terunobu Fujimori and other artists. I believe it was these roots that enabled Gaudi to find possibilities in architecture that were not headed toward Modernism.

In other words, I was greatly influenced by my serious delving into the Gaudi phenomenon and asking myself what was behind it. And that is the source of my conviction that things can only be seen in terms of region. I come to the conclusion that reality cannot be separated from region or place, and see anything else as being simply in the realm of fashion. So I believe that finding things that can be done in a specific region or community and doing it in that place is what leads to solid gains and results, even if they would be small. In Echigo-Tsumari, another theme seems to be coexistence with the natural environment, such as the terraced rice paddies.

I dislike the expression “coexistence with nature.” I think that it is much better to think in terms of the laws of nature. I believe it is presumptuous to speak in terms of seeking coexistence when the underlying attitude is one of controlling nature. I want to say “get back to a more primal state.” - You probably didn’t have that attitude when you started out in regional activities, did you?

-

No. I didn’t. But now I really feel that way. We who are involved in art speak about forms of expression and various such things, but in fact that isn’t what’s important. The important thing is that it is so interesting to be alive this moment in this space in the universe. And that experience is different for each of us and that difference is the true root of art, I believe. Art is not individual expression, it is just our manifestations of that different experience each of us has. That is something I have come to see very clearly.

Also, although it my be important, for example, to measure the height of Mt. Fuji in terms of numbers, there are also other forms of perception, ways of feeling things that cannot be measured quantitatively. What I have come to understand is that, rather than breaking down things into parts and organizing them into analytical packets, it is often more correct to feel them instinctively and emotionally according to our natures; and that is exactly what art has consistently done and what we can feel most proud of as the heritage of art. And I believe that this is a worldview based on human beings as a part of nature.

Toward new projects

- This year sees the start of a new festival you are involved in initiating, the “Niigata Water and Land Art Festival” in Niigata City.

-

Doing Echigo-Tsumari made me realize that for such a small country, Japan truly has very diverse and tremendously fascinating culture. What is the reason? I came to the conclusion that the reason can only be the land. Japan is an archipelago with coast washed by two black currents that bring warm temperatures and lots of rain. This creates rivers everywhere and many of them have very fast currents and rapids. You can surely say that this is most distinguishing feature of the Japanese islands. As a people who have lived on this land, our ancestors came to know the character of the land thoroughly. For example, even making the mounds that border the rice paddies and direct the flow of water requires a deep knowledge and understanding of the soil. Looking at the works of Koichi Kurita, an artist who creates works using soil gathered from different regions of the country, I realized what great variety there is in the colors of the soil found in Japan. Niigata in particular has an amazing variety of soil colors. They say the Earth is a planet of water, but it is also a planet of earth.

Thinking from that perspective, Niigata City is built on the delta of Japan’s longest river, the Shinano River, and the Agano River, which has one of the largest water volumes among Japan’s rivers. And that means that it is built on land that has been churned for ages by these two great rivers as they sought courses to the sea. About one fourth of the land in Niigata City is below sea level, and some parts are as much as 2.5 meters below the water level of these rivers. And on this land and its mud wetlands, the people of Niigata have created the largest rice-producing area in Japan, and perhaps in the world as well. It used to be land where farmers waded hip-deep in mud to plant their rice crops, but with tremendous effort over the decades they created the broad plain of rice fields we see today. There are many memories and records remaining of Niigata’s water and land, such as photographs of those farmers’ efforts and the ravages of the flooding waters in the past and the earthworks like the river overpasses that have been built.

In this year’s 1st Niigata Water and Land Art Festival, I wanted to see these memories of Niigata, including the local festivals and arts, celebrated as “treasures” of the region. Niigata City is the downstream end of the water system in which Echigo-Tsumari is at the upstream end. I wanted to make this festival one that sings the praises of the rice paddy-building culture that has evolved at these two ends of the Niigata water system and to see it in terms of the other river systems that have given birth to civilizations, like the Tigris and Euphrates and the Hwang Ho and Yangtze, and also the connections to northeast Asia that have extended out from Niigata’s rivers, so it will provide an overview of the path we have come and point to directions we may follow in the future. - You have also done art projects in Osaka, which along with Tokyo is one of Japan’s largest cities. You had the Osaka Art Kaleidoscope (2007, 2008) that brought together contemporary art with the Modern period architecture that remains in the city today, and this year you helped launch the Aqua Metropolis Osaka project.

-

Aqua Metropolis Osaka is a symbol project for the efforts by the city’s financial sector and the government to develop and revitalize the city. In the Edo Period, Osaka was Japan’s biggest commercial city thanks to water commerce that developed because of its seaport and the river system that laced the city. Until the 1910s it was a more active commercial center than Tokyo, and part of the wealth from that commerce went into social assets and infrastructure like the construction of bridges. Considering that history of hard-earned commercial success, “water” was agreed to be the defining theme for a campaign to revitalize the city.

For this project we have gotten famous Osaka artists like Kenji Yanobe and Noboru Tsubaki, and the NPOs like DANCE BOX to join in a program that proposes “100 ways to enjoy the waterside.” A bamboo structure called the Mizube no Bunka-za (Waterside Culture Theater) constructed on Nakanoshima island to present art and a variety of performances and concerts.

Osaka is also a city that has absorbed many immigrants from other parts of Asia who began new lives in the city. In the past that aspect of the city as an ethnic melting pot brought exceptional energy to Osaka. Today, a lot the city’s energy has been lost, so I hope this project will provide inspiration for the citizens and help restore some of the energy it once had as an ethnic melting pot. - Today there is a boom in art projects all over Japan. What do you think about this trend?

- I think it is due to the fact that people find art projects a bit more interesting than the other things going on. Art is something that everyone can enjoy in their own way, and it provides the opportunity for people to get together and make “much ado about nothing,” if you will, and build connections. That is the distinguishing effect of art, and I imagine that is what people hope for from these projects. But, I think it is best if these projects are done where there is opposition to overcome [laughs].

- In 2010, Setouchi International Art Festival 2010 will be held for the first time as a large-scale festival held on seven islands in the Seto Inland Sea. For this grand project, you have worked together with the Chairman and CEO of Benesse Corporation, Soichiro Fukutake, who with his company has been a leading promoter of contemporary art and initiator of art projects on the Seto Inland Sea islands of Naoshima and Inujima. Mr. Fukutake has recently founded a new Fukutake Foundation for Promotion of Regional Culture as further evidence of his dedication to these activities.

- What began at Echigo-Tsumari is something that I believe can be called a “gift.” By each person contributing a small gift in the form of labor, communication has been re-established. In other words, the countryside is a place that has that kind of capacity for rebirth and renewal. It is the same on the islands in the Seto Inland Sea; there is capacity and power for renewal. These are places that are saying anyone is welcomed and anyone can earn their daily bread there if they are willing to work, and the people there will help people from the city start a second life on the islands. I believe that these islands can be revitalized as that kind of place. It may take a couple of decades but I think that possibility is there.