- You were involved in inviting Asian performing arts productions and introducing them to the Japanese audience back in the 1980s before you joined the Japan Foundation. What is it that got you involved in the Asian scene in the first place?

-

When I was studying musicology in graduate school, my professor, Yoshihiko Tokumaru, was a supervisor of the Japan Foundation’s “Asian Traditional Performing Arts (ATPA)” program launched in 1976, and through him I became one of the research staff for the project.

In the early years after the Japan Foundation was established back in 1972, the programs centered mainly on introducing Japanese culture and arts abroad. The Foundation had been established with the dual aims of promoting overseas understanding of Japan and also increasing understanding of foreign cultures by the Japanese. In order to promote this kind of mutual understanding with other countries, a project was launched to introduce Asian performing arts that were until then relatively unknown in Japan. Eventually this project went through five three-year cycles of surveys and plan-making the first year, performances and seminars the second year and record compiling in the third year. In each cycle there would also be a rich array of peripheral programs like the large-scale mask exhibit titled “Gods Incarnate – Exhibition of Asian Masks” that we organized in connection with the cycle on Asian mask theater. The record included the detailed report book in English which not only recorded the results of the seminars that had been held but also added a lot of subsequent research result, music records, and films, etc., to create valuable resource materials that have entered many university libraries around the world. - That was truly a revolutionary project at the time, wasn’t it?

- In the Japan Foundation at that time we had some highly motivated young people who worked with dedication on the planning of projects and getting researchers involved to carry them out. That is what made the projects so successful. It all began with gathering existing materials and documents, but then that proved to be insufficient, we began going to the various Asian countries to do our own surveys and research. It was very much like the type of fieldwork that is done in ethno-musicology.

- What types of actual performance programs came out of the project?

-

The first two cycles were done in a format where we presented various countries traditional arts in the context of how they compared with Japan’s traditional arts. For example, one case compared the forms of Indonesian traditional music with that of Okinawa, and another compared the vocalization used in traditional Mongolian singing with that of Japanese folk singing. But doubts arose about this kind of format because it could also be seen as an attempt to find the roots of Japanese culture. So, from the third cycle we began introducing the Asian arts individually without the Japanese comparison component.

In the early stages of the project there had been a strong emphasis on seminars, which were quite academic in nature, but gradually a greater emphasis came to be placed on the performances themselves. In the process we came to organize the programs so that they have considerable value and significance as stand-alone performance programs. The themes of the programs were Asian mask theater “Theater of the Gods” for the third cycle (1981), the arts of traveling performers “Itinerant Artists of Asia” for the fourth cycle (1984) and the arts of prayer “Dance and Song of the Asian Spirit – Expressions of Love and Prayer” for the fifth cycle (1987). - Then in January of 1990 the “ASEAN Culture Center” was formed within the Japan Foundation to specialize in culture and arts exchange with the ASEAN region. This ASEAN Culture Center was established with the aim of deepening mutual understanding with the ASEAN region and to aid in the forming of new partnerships of the kind the Prime Minister Takeshita proposed in 1987 with his “Japan-ASEAN Comprehensive Exchange Program.” How did you become involved in this ASEAN Culture Center?

- The ASEAN Culture Center became the first public sector organization in Japan to introduce Asian arts, and since I had been working at ATPA in a capacity that was somewhere between a researcher and producer, I was asked to take a position as a coordinator in the performing arts section and participate in the planning stage. I also participated in the study mission to determine what directions the Center’s activities should take, and in that capacity I went around the ASEAN region interviewing intellectuals and artists. From them I was given some very frank but passionate opinions about what we should try to do. That experience inspired me with the idea that we could do more than just ride the “ethnic arts boom” and take a more solid stance. Besides me, there were specialists appointed in the fields of film and visual arts, and I believe this represented a rather revolutionary approach for the Japan Foundation at the time.

- What sort of policies did you have in the performing arts section at the start?

-

For the film and visual arts sections, as well as our performing arts section, “contemporary” was definitely one of the key words in our focus. In the performing arts field, there had been an increasing number of programs introducing traditional Asian arts, as with the ATPA projects I mentioned earlier, and along with the ethnic arts boom beginning in the latter part of the 1980s there was also an Indonesian gamelan music boom. However, there were not enough opportunities to see Southeast Asia in a contemporary eye. In the study mission I mentioned earlier we also found the contemporary to be a direction we should pursue.

I especially thought that it would be important to introduce the region’s contemporary theater. Although it would be much easier to introduce music and dance [due to the absence of the language problem], I thought that in terms of sharing what our contemporaries were thinking, theater would be the most effective genre. Theater is difficult for private sector presenters to introduce because of the difficulties of translation and the cost, and in fact there were almost no theater productions being invited to Japan at that time. So, I thought this was an area that the Japan Foundation should take the initiative in.

As a result the Center’s opening performance was a production titled The Ritual of Solomon’s Children by the Indonesian poet, playwright and director, Rendra of Bengkel Theater. This was the first theatre work by Rendra, who was eventually labeled an anti-establishment activist and imprisoned. It was originally performed in the late 1960s. It was a time when Indonesia and much of Southeast Asia was confronting the problems of modernization and individual confrontations, and the fact that this play dealt directly with these problems in the script surely made it a very avant-garde work for its day. This makes it one of the important plays that must always be considered when speaking about contemporary theater of Southeast Asia. One of the things that I recall most clearly from that performance in Japan was one Japanese theater professional who commented after seeing the performance how moved he was to discover how, during the same period in the 60s when Japanese theater people were rejecting the established form of theater and turning their efforts to the avant-garde “small theater” movement, people in Indonesia were doing the very same thing. It can be said that this opening production by the Center was a statement concerning the course it would take from that point onward. The plays that were introduced after this included the joint Singapore and Malaysia production Three Children , the Singapore production Beauty World , and the Philippine production El Filibusterismo , etc. In 1995, when the ASEAN Culture Center was reorganized as the “Asia Center” were there any changes in the operating policies? - Since it became the Asia Center, the area that we now dealt with was all of Asia, not just the ASEAN region. Other than that, the basic focus on the contemporary hasn’t changed. At the same time, a new department was established to be in charge of exchange programs involving intellectuals in various fields, and regardless of whether it was in the arts or in intellectual exchange, the sense of direction became clearer: the aim was to stimulate exchange within the region, which is something that we knew we could contribute to not only with programs directly involving Japanese artists and intellectuals but also ones in which Japan merely served as an intermediary to bring about exchanges.

- It would seem that there is quite a leap from the idea of inviting foreign productions to Japan as they are and the idea of organizing international collaborative productions.

-

In my mind there is quite a natural connection between the two. When inviting a contemporary theater production, it is important to get a good understanding of what the play is about, and to do that I spend a good amount of time talking to the director; and of course I also have to think about it myself. And then from the understanding I get, I have to plan how to best introduce it to the Japanese audience. There is a feeling that I am working together with the director to bring new expression to the presentation based on what I have come to understand about the play. In this process, an invited work is in fact the same, in a sense, as creating a new production. That is why there was a natural transition to the international collaboration project for producing new works. The large-scale Philippine musical,

El Filibusterismo

(Subversion), is a good example. This was a reproduction in musical form of the famous novel by Jose Rizsar depicting the eve of the Philippine Revolution and it brought a very big response when it was performed in Japan in 1993 as

El Filibusterismo

(Subversion). After that, we asked its director, Nonon Badillia, to do a production of

Noli Me Tanjere

(Touch Me Not) to create a diptych with

El Filibusterismo

, which was then brought to Japan for performances in 1995. In fact,

Noli Me Tanjere

tells a story that happens before the story of

El Filibusterismo

, so it was actually a process of going backwards in terms of the creative process, but the scriptwriter and composer worked with great passion on the production and made it a success. Even if

El Filibusterismo

is an exceptional case, I believe that it shows how working diligently on the production of an invited work can naturally connect to creating new works collaboratively.

I also believe that our international collaboration project is a very effective method for introducing works. Even if you had a program where you introduced a work from a different country each year, the number of countries you could actually introduce works from would not be large. However, in our two-stage collaborative project titled Memories of a Legend involving five South Asian countries during in a period from 2003 into 2004 for example, we were able to present one short existing work from each of the five countries in the first stage and then in the second stage the following year we did collaborative productions of a new work. If we had been working individually with the five countries, it probably would have taken five years, and we might not have gotten around to working with some of the smaller countries such as Nepal or Sri Lanka in the first place. - Do you have any specific policy guidelines for choosing your invited works?

-

First of all we are concerned with the strength of a work and the artistic level. Even if we may feel affinity or empathy for the message of a work, it will not become a candidate for selection unless it has the necessary artistic strength to succeed as a theater production. No matter where they are from, I am attracted to works that have an intensely strong sense of that country’s reality. For example, the first time that I saw the Ilkhom Theater’s production of

Imitations of The Koran

in Uzbekistan it was such a powerful experience. I will never forget that shock. I don’t want to reduce it to terms of politics or religion, but the underlying realities of their lives I was confronted with so strongly in this work was a shocking revelation for me. Also the Philippine musical

El Filibusterismo

was another work that won my heart in the same way.

There is tremendous responsibility in choosing just one work out of so many possibilities. Because that single work you choose will color the Japanese audience’s impression of that country’s theater. So, to make these choices I first go to the country in question and see an actual performance of the work there. In cases when that is not possible I watch a video of a performance. And I will also talk several times at length with the director of the production. And, behind every individual work I choose, there are always dozens more that helped guide me to that decision. - How about your process for choosing artists to work with for your international collaboration projects? One of the first artists you worked with on the productions Three Children and Lear was Ong Keng Sen, who today is one of the most acclaimed among the active Asian artists in theater. How did you come to work with him?

- When I first met Keng Sen, he was still in his 20s, but he already had his own unique vision and he was able to talk to me about in very clear words. When people come from different backgrounds, I believe that the process of expressing in words to make our thoughts clear to each other is very important. When I saw this young director in the young country of Singapore with such a clear vision of the future and the present conditions, I thought that it could be very good to work with him, for the stimulus it could bring Japan as well. And after that we continued to actively work with young and middle rank artists in cooperative efforts, which has the potential to grow by working jointly with others.

- Could you give us some examples of how you go about creating a theater production for the Japan Foundation’s international collaboration program? How was Lear created, for example?

- In the case of Lear , we had first of all decided to do a production with Keng Sen. We had already invited a production of his very successful work Beautiful World to Japan, and through working with him on the short collaborative production Three Children I knew a good deal about his way of thinking. Based on that experience, we talked with him extensively about what kind of production we should undertake. He said that for the task of looking at Asia, he wanted to borrow the eyes of a woman, and he requested that he be able to work with a Japanese woman playwright. So, we suggested Rio Kishida as someone for him to work with. Also, at the time, Keng Sen had a strong attraction to the traditional, and he wanted to work with people who could take traditional Asian physical expression and movement and “reinvent” in the present (this “reinvent” was a word that he often used at the time). We held auditions in several Asian countries to choose the actors, dancers and musicians for the production. From Japan we chose the Noh actor Naohiko Umewaka and from China we chose the Peking Opera actor Jiang Qi Hu, this turned out to be a very difficult process. By the time the rest of the necessary staff and cast had been chosen, we had people from six countries, including Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand. From Japan we also got Hairi Katagiri to participate. By including her, with her contemporary Japanese “small theater” movement orientation, we were hoping to have her symbolize contemporary Asia among these other artist specialized in the traditional forms of physical expression.

- For Memories of a Legend you had several directors come together to do a collaborative work.

-

For

Memories of a Legend

we chose one director each from the five countries of Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan and each of them were asked to recommend three actors that they wanted to work with in an attempt to create a multinational collaborative production. As I mentioned earlier, we first invited five existing short works by the directors for performances in Japan. The purpose of this was not only to give the Japanese audience an introduction to these directors’ works but also to give the directors a chance to get to know and understand each other’s working methods. After that, all five of the directors got together in India for a short workshop before going to Japan for a more extended stay, during which they created their collaborative work. I knew from the start what a stretch it was to expect five artists to create one work and I anticipated that there would be problems and perhaps criticism as well. But I wanted to see what could be done with a collaborative working method—difficult as it might be—in which not one but a number of artists would be bringing to the work equal amounts of responsibility and decision-making rights. So, I made the quite demanding request that they collaborate in this way.

Then, for our latest work this year, we had three directors from India, Iran and Uzbekistan come together for the production Performing Women , and we asked you to serve as project advisor. The production took the form of a trilogy, and each director did one work on the common theme of Greek tragedy.

This form of production perhaps contains some risk in terms of production quality compared to the usual style where all the decision-making rights are entrusted to the talents of a single director. On the other hand, having a single director direct a production with a multinational cast is quite commonplace in the world of opera. However, I believe that the real significance of international collaboration is having people of different cultures and different methodologies working together on a production on an equal standing and with equal decision-making rights. And that may not always mean having joint directorships, but this basic concept of multicultural artists working on equal standing is one that I want to continue to pursue. Of course, most important of all, however, is the substance and quality of the resulting work. Because that resulting work is the only form in which the meaning of the project can be communicated. No matter how wonderful the production process might have been, it is meaningless if the resulting work is one of inferior quality. After Lear there has been almost no participation of Japanese artists in your projects. What do you see as the role of Japanese artists in the Japan Foundation’s international collaboration program? -

Even though Japan is taking the initiative in these programs in the economic and organizational (planning) aspects, I don’t believe that necessarily means that the programs should by Japan-centered. As I mentioned earlier, I believe that if Japan can stimulate exchange in the region by serving as an intermediary, that positive results of that effort will come back to us in rewarding forms. Also, although there may be few Japanese actors involved, Japanese are playing an important role in other areas of expertise like stage plans and technical operations, and in those capacities they may actually be more involved in the creative discourse than actors would be. Of course, I also think it is great if Japanese artists come forward and say that they definitely want to participate in a project.

Since the role of the Japan Foundation is neither that of a production company or that of a promoter, I believe that what we should be doing as an organization is to offer new models for ways to do collaborative works. Whether it is inviting existing works to Japan or producing new collaborative works, the aim is to show our audience that there are people in Asia thinking these different thoughts and expressing themselves with these different creative vocabularies, and in that way to create the interest and foundations for future collaborative works. So, even if it only happens once in a few years, I want to see us show these possibilities in a way that has real impact. -

In Japan there is still the idea that international collaboration on works is an unusual thing and people ask for explanations of why it needs to be done, but in the West it is known as multiculturalism and considered to be a natural practice. That gap is something that you alone cannot fill in, but having been involved in your projects in an advisory capacity, I have felt that what you have done by presenting specific new working methods and aesthetics to the Japanese public and Japanese artists has been important in terms of the pursuit of new models for artistic and cultural exchange.

It has been almost 30 years since you personally became involved in Asian performing arts exchange. During this time the relationships between Japan and the countries of Asia have changed a lot. I would like to ask you what kinds of changes you have observed in the field the performing arts. - There have constantly been exchanges with theater people in China and South Korea, compared with other Asian countries. With regard to Southeast Asia, there was almost no exchange going on at the time of the founding of the ASEAN Culture Center. In the dozen years or so since then, there has been a considerable increase in collaborative work with this region. Some examples are the collaborative work Rinkogun Theater Company has done with Philippine artists, Ku Na’uka Theater Company’s work with Indonesia’s Theater Garasi and the Setagaya Public Theatre’s Contemporary Asian Theater Project. There have also been cases of Japanese actors going to study in Indonesia, or studying at a theater school in Singapore. These types of things were virtually unthinkable at the time the ASEAN Culture Center was founded. And now, the Japan Foundation’s policy is to shift to areas of Asia like South Asia and Central Asia, and the Middle East, that are still lacking in this kind of cultural and arts exchange with Japan. Our recent Performing Women is an example of this shift.

- By the way, what kind of audience comes to see your international collaboration works?

- Unfortunately, people who are otherwise Asia fans don’t necessarily come to see Asian theater and theater fans rarely come to see unknown Asian works. With Performing Women we wanted not only Asian fans but also a wider section of the general public to see the work, so we scheduled the performances at one of Tokyo’s major theaters, the Bunkamura Theatre Cocoon. Still it was a struggle to get a sufficient number of people to come see it. I feel that, regardless of whether it has to do with Asia or not, Japanese theater fans are quite closed-minded when it comes to things they don’t know or don’t understand. And, I believe that it is the job of the Japan Foundation to break through that resistance and get people to look to the world outside.

- While you have been pursuing the Asian collaborative works program over the years, have you found any cooperative partners to work with on an ongoing basis?

- There are individual artists with who I want to continue to work, but in terms of building ongoing cooperative relationships with organizations, it has been more difficult. Speaking generally, the benefits of economic development have not filtered down to the field of collaborative projects in the arts, and so it is hard to find organizations that we can really work closely with. In the area of arts festivals, the established festivals of Hong Kong and Singapore have been joined in recent years by new arts festivals in a number of countries, and they are promoting the Association of Asian Performing Arts Festivals as in network for these festivals, but it is still very rarely that a collaborative production comes out of this festival network. Anyway, I believe that it is very important that we break out of the established pattern where Japan alone is providing the funding for collaborative projects if we are ever going to have real development of collaborative programs.

- As a presenter, are there any artists or companies now that you think are especially interesting?

-

Having just done

Performing Women

, I am especially interested now in Central Asia and Iran. Mark Weil of Uzbekistan’s Ilkhom Theatre, who tragically passed away in September, was certainly one of the Central Asia’s great directors, and so is Ovlyakuli Khodjakuli, who participated in the

Performing Women

project. Among the younger generation, there is an interesting Russian-ethnic women’s company called Art & Shock Theater in Kazakhstan. For these women in their 30s, Kazakhstan was still part of the Russian dominated Soviet Union in their childhood years, and their production

Back in the U.S.S.R.

that I saw looked back on that era partly with nostalgia and also a good portion of sarcasm. It was thoroughly enjoyable and really made me laugh, and I sensed their talent be so strong and sturdy. This work was performed at the Kijimuna Festa in Okinawa, Japan, this summer.

In Iran there is a system of government support for theater companies, so the theater people can make a living at their art, but that support is coupled with considerable restrictions and censorship. There are a number of outstanding young artists who are trying to turn this conflict into creative energy and produce excellent works. Among these are the two artists Amir Reza Koohestani and Hamed Taheri, who were both candidates for our last project. Both in their early 30s and both are artists that I would like to work with in the future. They are invited every year to venues in Germany, France, etc., and are thus spreading their range of activity internationally. And, it is disappointing that Japan cannot make the stage for them. - Could you tell us what you find to be the greatest appeal of Asian theater?

- I feel that Asian theater people are deeply aware of the meaning in doing theater, the reality. And, I believe that the clarity of their reasons for doing theater works and the clarity of their concepts communicates directly to the audience and moves them. I also have the belief that societies with strong traditions make for strong contemporary art. Indonesia and India are good examples of this, and lately I have also come to see Iran in this light too. A high level of traditional culture becomes the stimulus that can be the driving force behind the creation of new art and culture, and when that combines with a strong will to make a statement about something, the result can be very powerful works of art. This is the potential that Asia has.

Yuki Hata

Connecting the theater people of Asia The Japan Foundation international collaboration program

Yuki Hata

Yuki Hata studied musicology at the doctoral course of Ochanomizu University. While doing her Masters degree studies she participated the Japan Foundation’s Asian Traditional Performing Arts program as a research staff member and became involved in introducing performing arts from the various Asian countries to Japan. In 1989 she joined the newly founded ASEAN Culture Center (later renamed Asia Center) of the Japan Foundation as the Performing Arts Coordinator, and since 2004, she has been the same Coordinator at the Performing Arts Division of the Foundation. Throughout these activities Ms. Hata has been involved in presenting the contemporary performing arts of Asia.

Interviewer: Tadashi Uchino, Professor of Tokyo University

Asian Traditional Performing Arts (ATPA)

This project introduced Asian traditional performing arts to Japan in a series of five programs beginning in 1976 that involved performances, seminars and reports. The titles of the five program cycles were “Asian Musics in an Asian Perspective” for cycle one (1976), “Musical Voices of Asia” for cycle two (1978), “Theater of the Gods” for cycle three (1981), “Itinerant Artists of Asia” for cycle four (1984) and “Dance and Song of the Asian Spirit – Expressions of Love and Prayer” for cycle five (1987). The regions represented included East Asia, Southeast Asia, and South Asia and as far west as Iran and Turkey. Pamphlets and English-language reports on these five programs can be viewed in the Japan Foundation Library. Recordings and 16mm films of the performances are now out of print but some of the soundtracks are available in the JVC WORLD SOUNDS BEST 100 series. A book on the Itinerant Artists of Asia program is published under the same title (Asahi Bunko edition published by Asahi Shimbun; 1985).

+ Reports published in English

“Asian Musics in an Asian Perspective – Report of Asian Traditional Performing Arts 1976” (Heibonsha Limited, Publishers; 1977. Re-released by Academic Music in 1984)

“Musical Voices of Asia – Report of Asian Traditional Performing Arts 1978” (Heibonsha Limited, Publishers; 1980)

“Dance and Music in South Asian Drama – Report of Asian Traditional Performing Arts 1981” (Academia Music Ltd.; 1983)

The Japan Foundation Contemporary Theatre Program

A Collaboration of India, Iran, Uzbekistan and Japan

Performing Women – 3 Reinterpretations from Greek Tragedy

(0ct. 2007 at Bunkamura Theatre Cocoon)

Indonesia: Bengkel Teater Rendra

Selamatan Anak Cucu Sulaiman

(Jan. 1990 at Laforet Museum Akasaka)

This is a work by the Indonesian poet, playwright and director, Rendra (1935—). To escape the persecution of anti-government intellectuals in the closing years of the Sukkarno regime, Rendra lived in the United States from 1964 to ’67, and soon after returning to Indonesia he established the Bengkel Theater in the city of Jogjakarta in central Java. This work was the first one performed by the new company. His plays, which took as its themes the threats and deceit of the collective during the period of modernization and criticism of inhibition of the individual and the increasing dependency of society on technology but presented them not righteous proclamation but in a style that dismissed with comprehensive storytelling and dialogue in favor of serenity and abundant use of the non-verbal vocalization and the strong physical expression of the Java poetry and song traditions created a sensation among the people and immediately propelled Rendra into a position of leadership in the period. As a result of these activities, Rendra was imprisoned in 1978, and after his release he was forbidden to engage in any public activities until 1985. This performance in Japan was only the second overseas performance of Rendra’s work after his return to public life in 1986, following one in the US.

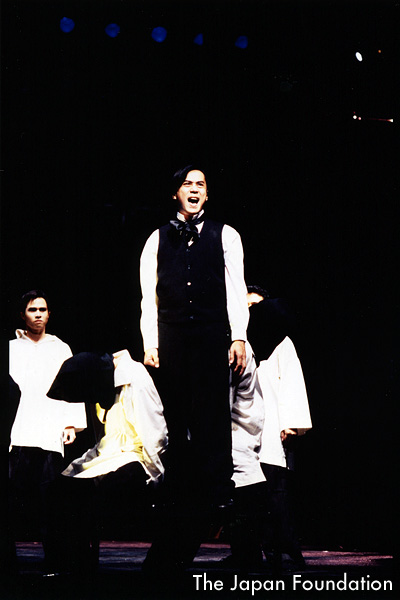

Philippines: Tanghalang Pilipino

El Filibusterismo

(Sep. 1995 at Bunkamura Theatre Cocoon)

This is a large-scale musical based on José Rizal’s El Filibusterismo (Subversion) , a play that depicts events on the eve of the Philippines’ independence from Spanish rule. It was produced in 1991 by the Philippine Cultural Center affiliated theater company, Tanghalan Pilipino. With its weighty subject and moving music by one of the Philippines’ foremost composers, Rayan Cayabyab, the outstanding vocal power and artistry of the cast of performers, the production was a huge success as a Tagalog musical. Performances in Japan in October 1993 deeply moved Japanese audiences as well. In response to calls for an encore, a production of the prequel to El Filibusterismo (Subversion) , titled Noli Me Tanjere (Touch Me Not) , was created under the international collaborations program of the Japan Foundation. Performances of this production of Noli Me Tanjere and El Filibusterismo (Subversion) were performed in Japan in September of 1995 as a diptych in consecutive afternoon and evening performances that were once again greeted with high acclaim.

A Collaboration of China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Japan

Lear

(Sep. 1997 at Bunkamura Theatre Cocoon)

A Collaboration of Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka

Memories of a Legend

(Nov. 2004 at Japan Foundation Forum)

Related Tags