Yuri Yamada

Playwrights’ Guide to Their Own Works Vol. 3 ー Yuri Yamada on I’m Trying to Understand You, But

Photo: Atsuharu Ino

Photo: Atsuharu Ino

Yuri Yamada

Yamada is a writer, director, and actor born in 1992, in Tokyo. She began her theater company ZEITAKU BINBOU while attending Rikkyo University, writing and directing all its productions. Her works are known for seamlessly blurring the boundaries between stage and audience, reality and alternate worlds, normalcy and madness, while playfully addressing contemporary social issues in Japan with boundless imagination and diverse methods. Her works Fiction City (2017) and Mixture (2019) were nominated for the Kishida Kunio Drama Award. Yamada has been expanding her activities both in Japan and abroad, with Everyone Fears the Night (2015) touring in China and I’m Trying to Understand You, But (2019) staged in Paris as part of the official program of Festival d’Automne.

She is active as a writer and director for television, and writes novels and columns. Her screenwriting credits include Abema’s 17.3 about a sex, 30 Made ni to Urusakute, and NHK’s She Loves to Cook and She Loves to Eat. She also wrote and directed the WOWOW series Ningen Kowai. Her first collection of original essays will be published in fall 2025.

In the third installment of this series, in which playwrights describe their own works, we introduce I’m Trying to Understand you, But, a signature play by Yuri Yamada, director of ZEITAKU BINBOU. This piece depicts the ties between the individual and contemporary society with an objective and pop-like brightness. In 70 well-crafted minutes, the work explores feminism, as it examines the “dis-communication” between men and women, questions their inability to understand one another and what lies beyond the attempt to do so.

Interviewing Yamada is yumei representative Ryo Ikeda, who applies a frankness to his portrayal of the relationship between the individual and the family or society, and has written and directed such plays as Heartland (68th Kishida Kunio Drama Award) and Yojo (Curing) (32nd Yomiuri Theater Awards Excellent Director Award). As playwrights, directors, and theater company leaders of the same generation but different genders, the pair trace back over Yamada’s origins as an artist and, through their dialogue, probe the deeper layers of this work.

Interview: Ryo Ikeda

Text: Miiko Okada

English Translation: Yume Morimoto, Ben Cagan (Art Translators Collective)

I’m Trying to Understand You, But

Written and Directed by: Yuri Yamada Music: Yuumi Kanemitsu

Cast: Momoko Shimada, Masayuki Yamamoto, Mayu Sakuma, Konomi Otake, Sachiko Aoyama

Feb. 13–Mar. 3, 2019

Bukatsudo Hall, Kanagawa / VACANT Harajuku, Tokyo

Distributed in a joint project of EPAD and the Japan Foundation

Synopsis

Teru and Koh are in a state of semi-cohabitation, and seem just like any other couple. One day, Teru finds out that she is pregnant, and confides in her friend Mei. Wracked by doubts and anxieties about marriage and pregnancy, Teru struggles to open up to Koh. Then the situation takes an unexpected turn that draws in Mei and the home’s mysterious maids.

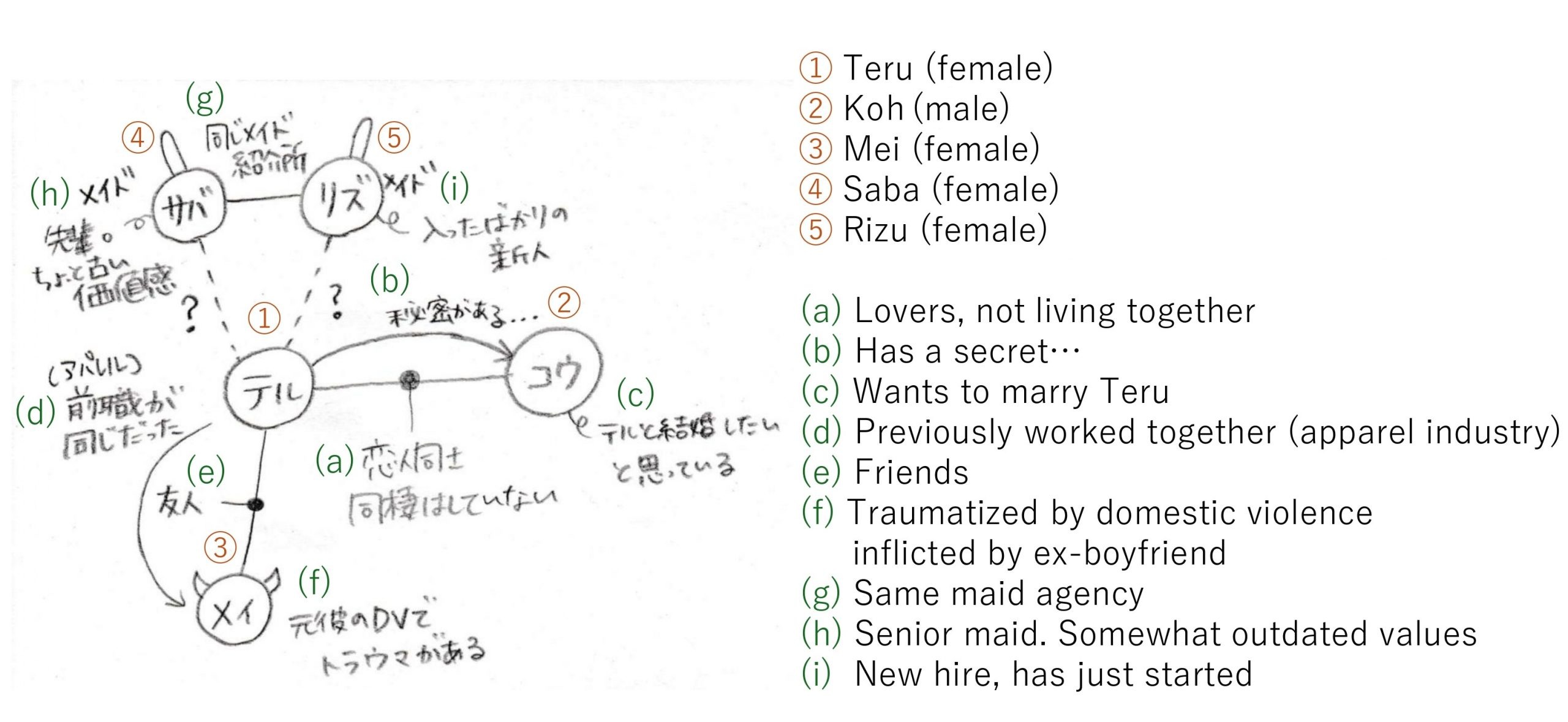

List of Characters

Teru (female)

Koh (male)

Mei (female)

Maid Saba (female) [Prudie in subtitles]

Maid Rizu (female) [Libby in subtitles]

-

Character relationship chart for the original production of I’m Trying to Understand You, But, created by Yuri Yamada

- Ikeda: As fellow playwrights of the same generation, both active in Tokyo, we’ve spoken on various occasions, starting with a public talk after the first production of I’m Trying to Understand You, But. Today, I thought it would be good to get into an even deeper conversation. To get things going, could you tell us about your background in theater? Your acting career began with work as a child actor, is that right?

- Yamada: My older sister had also gotten into acting as a child, so I joined a children’s theater group before starting school. I had my stage debut when I was in second grade, in 1999, as Little Cosette in Les Misérables at the Imperial Theater. It really was a spectacular debut, being surrounded by such a distinguished cast like I was. But at the time, I didn’t fully grasp the gravity of the work, so I’d sometimes get scolded for getting too excited and carried away [laughs]. I still have vivid memories of moments from that production: the dazzling lights during my solo, my mother in the wings praying that I wouldn’t miss my first note, the scene where I walk hand-in-hand with Sakae Takita, as Jean Valjean, and him patting my head and telling me I was the best Little Cosette. Looking back on it now, as an adult, it really was an awe-inspiring experience. I stopped working as a child actor when I entered junior high school, and focused on school life, but I always had the intention of returning to acting someday.

-

Yamada as Little Cosette in the musical Les Misérables at the Imperial Theatre (1999).

- Ikeda: I understand your high school had a strong theatrical focus, is that right?

- Yamada: The school I went to, Tokyo Metropolitan Aoyama High School, was the kind of place where every classroom across all three grades would have a stage set up for the school festival, with around 15 performances going on simultaneously over two days. We borrowed programs from groups like Shiki Theatre Company and Caramelbox, and students even led the negotiations for performance rights. The productions were double-cast and we had four performances a day, so the scripts were edited down to around an hour, and we spent our summer breaks deep in rehearsals. Once I took the lead role, and other times I directed or choreographed. There were sections for scriptwriting, lighting, sound, costumes, and so on. Everyone helped in some way—even students who were really busy with other club activities took part on the day, doing things like lighting. We all enjoyed taking part, and when the performances came around there would not only be students’ family members in the audience, but also a big turn out from the general public.

- Ikeda: So, putting shows together and performing them in classrooms was the starting point that led to your later productions in houses and apartments.

- Yamada: It was so fun being able to work on a play with friends from the baseball club, for example, who I’d never normally have engaged with in a theatrical context. I think that feeling has also fed into my approach to theater since college.

- Ikeda: And you launched ZEITAKU BINBOU while studying at Rikkyo University’s Department of Body Expression and Cinematic Arts.

- Yamada: The first time I wrote a script was when I made a film with the independent film club in my first year there. As a sophomore, I started wanting to take a look at more diverse forms of theater, so I poured most of the money I earned into working part-time buying theater tickets and regularly going to Shimokitazawa [one of Japan’s leading theater districts, boasting the densest concentration of small venues in Tokyo]. Keralino Sandrovich’s absurdist plays had the most profound impact on me. I started reading scripts by people like Minoru Betsuyaku and Koharu Kisaragi in the university library, which also had an influence on me having a go at writing my first play. I was able to have Kaku Nagashima, a professor at the university back then, read it. Although he had some harsh criticism for me, what really stuck with me was him saying, “First of all, it’s really admirable that you managed to finish a script.”

- Ikeda: Some people quit before they finish, and others are discouraged by harsh feedback, but you kept on writing after that. Was your motivation to keep going the desire to see actors performing something you wrote, and try directing?

- Yamada: One night, I had the idea of a one-person play where I’d tell the audience a

story I’d heard secondhand, wrote the whole thing in one go, and called a friend as soon as I’d finished to perform it over the phone. The friend said they liked it, and we should give it a go, so we rented a school hall and put the show on during lunch break. That was the start of ZEITAKU BINBOU [luxury poverty]—the name we used when applying to the university to use classrooms for rehearsals ended up becoming our group’s name. Eventually, someone who came to see that solo performance said they’d like to be in our next show, if we did one. So, then we did a two-person play, and then a four-person play, and it kept going like that. What I mean is, what allowed me to carry on writing was simply that there were people around me saying, “Let’s do it.” I didn’t have any money, but I did have friends, and those days figuring out how to put on plays and make films together really were a kind of “luxury poverty.”

-

Solo performance Super Mirror (2012) at Rikkyo University Niiza Campus STAGEBOX

- Ikeda: “ZEITAKU BINBOU” is a very memorable name. There’s the linguistic sense in which it’s interesting to have these contradictory words, and I feel that the name’s connected to your theatrical vision and style, how you approach the art from a perspective close to everyday life. And, speaking as a playwright of the same generation as you, the uchi-project1 was quite a shock to the system. This also feels like a continuation of what you were doing since your high school days.

- Yamada: Breaking out of university to put on a show at a small theater with ZEITAKU BINBOU for the first time, I was made keenly aware of how much better it is to be able to rehearse in the same space you perform. So I rented a 50-year-old house. Since we were going to the trouble of renting a place anyway, I figured a two-story house might offer more possibilities than a single-story, in terms of letting the audience swap floors while watching, so we went with that. I wanted to create theater rooted in where we were—the house and the specific locality—so I lived there for half a month, working part-time jobs locally while developing works. Renting a house to stage a performance means taking on management of the space as well as the creative work. Back then, I was also involved in production work, things like deciding how many performances we need to put on to cover expenses like rent and pay for the actors, so I developed the kind of financial awareness you need to do theater.

We had total control of our schedule, and there was this feeling that we were able to achieve something we couldn’t have done within a conventional theater. Looking back on it now, we’ve been creating theater in a way that defies the Japanese small-theater sugoroku2 from the beginning—we weren’t tied to that mindset or context. Most of the people we worked with had never even seen a play. I think that’s what let us just focus completely on our creative process.

-

Hawaii Yuu (2016), part of the uchi-project, performed in an apartment building. Photo: Kengo Kawatsura

- Ikeda: Now, of course, Japan has plenty of immersive theater productions that take advantage of non-traditional theater spaces, but I think ZEITAKU BINBOU was truly groundbreaking. The more I find out about ZEITAKU BINBOU, the more I find that you’ve done so much that I want to do with my own theater company. In other words, you’ve already beaten me to everything [laughs].

- Yamada: But I never had the idea of wanting to do something unprecedented in mind. It was just wanting to rehearse at the venue to improve the quality of the performance, and to be able to put on a long run so more people could come, that led me to put on a show in a rented house. And then having done that, using whatever was in the house to build the production seemed like the natural, obvious thing to do. So, I was tremendously confused the first time we staged anything in a big theater. It was bewildering when the audience suddenly jumped from ten to twenty people per performance to around 200. I used to start conceptualizing a story by, for example, seeing a picture hook left on a wall in the house and wondering what I should hang there, so for me an empty black box was hard work. I was so desperate I’d have settled for the faded outline on a wall where a calendar had been, anything [laughs]! With Fiction City [a finalist for the 62nd Kishida Kunio Drama Award], which we staged at Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre’s Theatre East in 2017, we turned these concerns on their head by thematizing our questions and doubts about performing theater in a theater.

- Ikeda: In the same year as Fiction City, 2017, you also took Everyone Fears the Night [first performed in 2015] from an apartment in Mitaka to China. Speaking of operating outside the small-theater playbook, that kind of unorthodox expansion overseas is exactly the sort of thing I mean. What was the reaction like?

- Yamada: I was invited over by a Chinese producer who had seen our performance at TPAM (now YPAM) Fringe. It seemed like this intimate story, rooted in personal lives, felt fresh to a Chinese audience so used to grand productions in big theaters. It seemed like they really liked it, young women especially, saying it was the first time they’d seen a play that felt so much like everyday life and relatable to their own stories.

-

Chinese production of Everyone is Afraid of the Night (2017), performed by local cast. © Xixi Arts Center

-

uchi-project

Launched by ZEITAKU BINBOU in 2014, uchi-project involves leasing houses and apartments for long periods for creative work, rehearsals, and performances (uchi refers to a “house” or “home”).

-

Small theater sugoroku

Small theater sugoroku refers to the tendency to judge how a theater company will progress on the basis of the location, size, and reputation of the venues at which it has been performing. The term sugoroku here is drawn from the name of a game that involves advancing along spaces on a board.

-

Photo: Kengo Kawatsura(2019)

I’m Trying to Understand You, But (2025 Japan Tour)

Written and Directed by Yuri Yamada Music by Yuumi Kanemitsu

Cast: Minami Ohba, Masayuki Yamamoto, Mayu Sakuma, Konomi Otake, Sachiko Aoyama

Tokyo: Nov. 7–16, 2025 Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre Theatre East

*Selected performances with English subtitles and Japanese accessibility subtitles are available.

Kurume: Dec. 6–7, 2025 Kurume City Plaza C Box

Sapporo: Dec. 13–14, 2025 Creative Studio (Sapporo Cultural Arts Community Center, 3F)

- Ikeda: I’m Trying to Understand You, But was staged in Paris in 2022, and will tour three cities in Japan from November 2025. To start with, could you tell us about the work?

- Yamada: I’m Trying to Understand You, But is a work that explores gender differences and equality, while also functioning as a thought experiment to question whether gender equality is truly possible, and what equality really even means. There are physical differences that will always be there. With that as our starting point, in what way can people understand one another? It’s a story about communication in that context. It lasts 70 minutes, which I think makes it a relatively easy watch, even as an introduction to theater.

- Ikeda: So, what was it that made you decide to tackle gender differences and inequality in the first place?

- Yamada: When I wrote it, there had just been the controversial statement from a politician that “women are child-bearing machines,” and there were incidents of women being subjected to disadvantages during medical school entrance exams. There was a sense in which I approached the work as a kind of social resistance. Also, I was 27 years old, so I was starting to think about whether to have children myself, and I could feel that society had started to look at me in that context too… I hadn’t given much thought to gender disparities in society up to that point, and I was actually reluctant to make gender a theme in my work. But as I studied feminism, I couldn’t help but become keenly aware of how off things felt.

- Ikeda: I feel that the scenography, costume, and hairstyles in this work are also visually striking and unique. How do these elements connect to the inner work and underlying ideas of the piece?

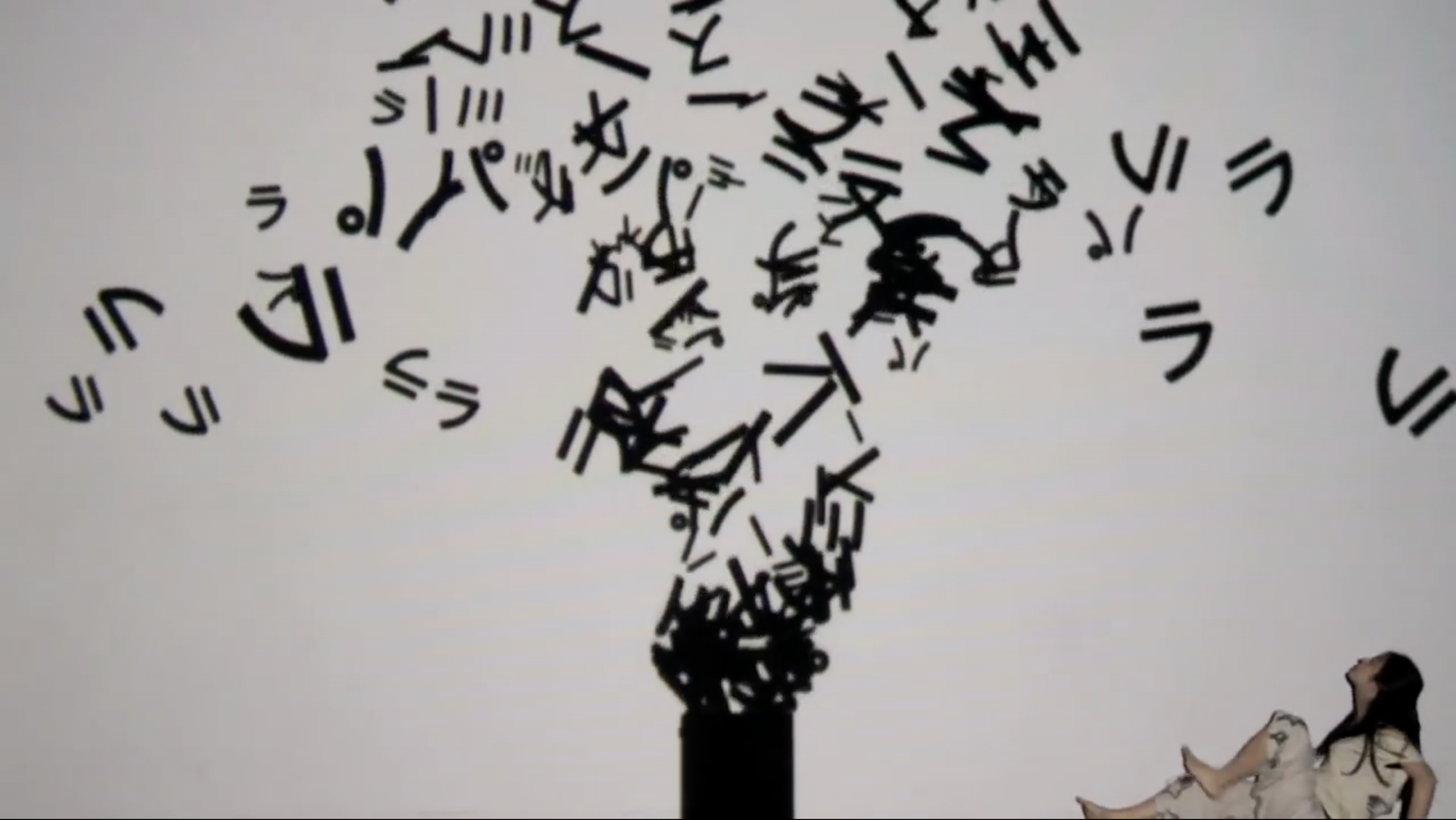

- Yamada: My interest surrounding gender differences and feminism did serve as a departure point for this work, but what first came to mind weren’t words, but rather, the visual elements. I sketched a composition featuring a man and several women dressed identically, facing each other across a long table. In the actual work, we see two somewhat strange female maids, who remain invisible to Koh, the only male character. These two maids are manifestations of the main female character’s inner mind, split into two. One of them is Saba, a conservative woman who has internalized values of the past, and the other is Rizu, a free-spirited woman who has internalized values of the future. Their names come from the words “conservative (consSABAtibu in Japanese)” and “liberalism (liberaRIZUmu in Japanese).” By placing these two opposing maids alongside each other, I felt it would give rise to a raw depiction of how women have been treated within society.

In my works, I tend to incorporate fantastical presences that add a light-hearted element, so that they don’t end up feeling too dark and raw. I had that in mind when I came up with the idea of the maids, but the more I thought about it, the more I realized that their presence actually highlighted gender-based differences. One aspect of this issue is how women’s domestic labor is made invisible. On stage, we see tea appearing as if by magic, or when the man is cold, he is brought a top, right in his hands. I thought that the invisibility of labor could be comically communicated through these moments, and through the fact that these maids cannot be seen by the male character. At the same time, it is perfectly valid to be inspired by domestic work, or to enjoy maid cosplay, or to dream of being moms and wives. I wanted to validate all of the different ideals of women that individuals may have, which is why I chose to have two maids, instead of just one.

-

Photo: Kengo Kawatsura(2019)

- Ikeda: The presence of the two maids was truly impactful, so it’s interesting to hear how these characters were devised. How was the response when you presented the work in France?

- Yamada: We had a full house, and the response was outstanding. I feel that France is a bit more progressive than Japan in its thinking, so I was afraid the work might be seen as based around outdated values. But in reality, far more people empathized with it than I had imagined. I was very grateful for this response, but at the same time, I felt that even in a country where gender equality has progressed more, the issue of gender difference hasn’t been resolved at its roots. I received comments like “Works that address feminism tend to have anger at its forefront, but it was refreshing to see something different that has a sense of kindness,” and it was also described positively by a critic as “an introduction to feminism.” On the other hand, there were also responses like, “Isn’t suppressing anger a form of self-censorship?” which was a reaction we heard in Japan as well. For me, however, I chose not to use anger as the central mode of expression. This was a strategy to more widely share the issues depicted in this work.

- Ikeda: I also think a lot about how to reach a wider audience, including the people I truly want to reach, with works that address certain issues. Was there a difference in response from Japanese audiences?

- Yamada: There’s a line in the work, where the man says to a woman, “You used to come over to my place and clean up for me.” When this line was delivered in France, the audience broke out into a roar of laughter. In Japan, it’s quite common for girlfriends to clean their boyfriend’s houses, so no one laughed. However, the French audience laughed loudly at that moment, as if such a thing were comically inconceivable. In the end, I even received a question from an audience member, probably around middle school or high school age, asking “Did you deliberately write the man to be immature?” to which I replied with a wry smile, “This is kind of the current state in Japan, where in many households, the norm still is that if the father says ‘beer’ a beer magically appears (in reality, it’s the mother who brings it).” I was then asked “Why don’t they just do things for themselves?” to which I had no answer [laughs]. In that sense, I was painfully reminded of how deeply patriarchal behavior is still rooted in Japan, and how domestic work is still so often defined as a woman’s role.

- Ikeda: This topic is a really hard pill to swallow. When I hear the words “Japanese men,” I picture myself, or the people who bullied me in middle school. After that experience, I came to feel that within homosocial settings, many have a relentless desire to dominate others, simply to boost their own egos. Although I share the same gender as these people, there’s a part of me that has given up, accepting that masculinity is not something that can be easily changed. Still, this is a work I hope will reach those who are constantly trying to satisfy their boundless pride—those caught within the axis of supremacy and inferiority defined by Japanese masculinity (a one-dimensional value system that is measured by hierarchy and strength). Through this work, I’m Trying to Understand You, But, which portrays people who are indeed trying to understand, I hope they begin to connect with the countless other axes that exist beyond that narrow value system.

- Yamada: Exactly! I had acquaintances and friends tell me, “This is a work I need to show my boyfriend.” Some actually brought them along, and others just sent their boyfriends alone to the theater to see it [laughs]. I got the sense that the work was serving as a starting point for conversation, so I do hope it continues to reach more people. That said, as you mentioned, it doesn’t always reach the people I most want to see it. I think it is an issue we need to keep addressing, including the more fundamental issue of how theater audiences are limited to begin with.

- Ikeda: Lately, I’ve been thinking about taking advantage of fields that have a broader reach than theater, like film or anime, since they can appeal to the masses more. Even people who aren’t interested in theater respond to widely known popular works, regardless of genre. We sometimes draw them in with that, then shift their attention to what we really want them to see [laughs]. That’s also why we create distinctively designed flyers and make unique handmade goods and accessories to sell. I hope that these can serve as entry points that lead people to experience theater in some form.

- Yamada: That really resonates with me. For me, I sometimes write scripts for television or radio series, and in those instances, it feels like I’m using mass media to get a social or political message across. In comparison, the audience for the theater is much more limited, since it’s a space for people who are deliberately going out of their way to see a performance. Even if someone comes based on a recommendation, they still have to take the step of buying tickets and making the effort to come to the theater, which requires intention. That’s why I feel that theater allows for a more assertive approach. While my theater works do carry social or political messages, the stage feels more like a space where I can freely research and explore my own thoughts on a certain issue, and present the outcome through performance.

-

yumei 10th Anniversary National Tour of Yojo

Written, Directed, and Designed by Ryo Ikeda

Cast: Ryu Motohashi, Tao Kurosawa, Heiji

Kyoto: Nov. 1–3, 2025 ROHM Theatre Kyoto North Hall

Mie: Nov. 8–9, 2025 Mie Center for the Arts Small Hall

Fukushima: Nov. 29–30, 2025 Iwaki Performing Arts Center Alios GS YUASA Iwaki Koko Gekijo

Hokkaido: Dec. 6–7, 2025 Creative Studio (Sapporo Cultural Arts Community Center, 3F)

Kochi: Dec. 12–13, 2025 Kochi Prefectural Cultural Hall Orange Hall

Kanagawa: Dec. 19–28, 2025 KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre (Large Studio)

- Ikeda: Exactly. I write about the things happening in my immediate surroundings, so I often get the critique that my works are like autobiographical novels. But for me, theater is about exploring and researching what is happening in society, and the stage is a place where we present the results of that process. In fields like television or anime, there have been moments where I felt that work in theater is seen as just a useful background to have. I want people who still feel that way to come and experience theater for themselves. There was actually a time when a video director came to see my work, overcoming that bias, and said to me “I misunderstood what theater was. I wish I’d known sooner that it could be this interesting.”

I’m Trying to Understand You, But is a work that stays with you after the performance ends, giving you a real sense that it will continue to affect you. Over time, you start to notice things you didn’t catch at the first presentation and the scenes and words that resonate can shift. I feel like even those who didn’t quite get it at first, or even felt that their behavior was being personally criticized can come to see it differently later on. The fact that we can watch it back on video like this also allows the work to have an impact that extends beyond a single moment or initial impression. - Yamada: I’m happy to hear that. A friend who’s seen the work multiple times said something similar. At first, they didn’t think much of the line “Don’t apologize” but later, it kept replaying in their mind. Before they knew it, they realized just how often they apologize, even when it’s not necessary. As a playwright, I think it’s incredibly valuable when the audience remembers an act from a play in their everyday life, and that continues to provoke thought.

- Ikeda: Pregnancy is an important subject that the work touches on. I myself got married and had a child in the past few years, and I experienced feelings I could never have imagined when the work was first staged. For women who are pregnant, it’s not just that their stomach grows, but there are various restrictions that arise, like not being able to eat or drink certain things, or move the way you’re used to. However, as a man, nothing changed about my body.

- Yamada: That’s totally right. The fact that only women have bodies capable of giving birth is something that can’t be changed, and the differences between men and women that emerge as a result simply cannot be erased. I studied feminism and thought about how we can eliminate gender differences and gender discrimination, but came to the conclusion that complete equality is difficult to achieve. So, then the question is where do we start? Thinking about this naturally led me to the words, “I’m trying to understand you, but.”

- Ikeda: For the first time in my life, I stopped drinking while my partner was pregnant. During that process, I realized that I don’t actually like alcohol that much, and that I was fine without it, so it wasn’t much of a struggle for me. It made me think about how we could be equal, or share the same struggle. When our child was born and we were able to drink together again, I felt really happy. I vaguely thought, “I’m glad I got to have this experience.” Maybe that’s just another version of “I’m trying to understand you, but.” The title of the work closed in on me, slowly but surely.

- Yamada: It’s impossible for us to understand one another completely, but unless we acknowledge that fact, we can’t speak on equal terms or achieve equality. When you’re pregnant, your stomach grows and you go through physical and emotional changes. It’s completely normal to have anxiety or feel a sense of dissonance. However, I felt that society often overlooks or makes these feelings invisible. I made this work with that in mind, so hearing you—a man—talk about this makes me very happy. I especially like the idea of a husband saying “I can’t drink because my wife is pregnant.” In addition to comments from people saying they wanted their partners or husbands to see the work, I also heard from people who said that it helped them take notice of the vague anxiety and despair they had felt after becoming pregnant. My hope is that this work can provoke thought on the issue of gender difference and open up conversations about equality.

-

Photo: Atsuharu Ino