Takuya Kaneshima

Playwrights’ Guide to Their Own Works Vol. 2 + Exploring Okinawa through the Performing Arts (3) ー Takuya Kaneshima on Backyard in RyCom

Photo: Naoko Kitaue

Photo: Naoko Kitaue

Takuya Kaneshima

Born in 1989 in Okinawa City, where he is currently based. In 2013, he formed the theater group chocodorobo (Chocolate Thief) and wrote and directed the group’s plays. He specializes in conversational dramas using the language of Okinawan youth, and stages original scripts centered on comedy and mystery. He is also active as part of the theater unit Tamadorobo with Ryukyu dancer Takumi Tamaki. In 2018, he won the Okinawa Prefectural Governor’s Prize in the scenario and drama category of the 14th Okinawa Literature Awards for Folklore. In 2021, he wrote the script for the NHK-FM theater Fushigi no kuni no haisai shokudo (Haisai Shokudo in Wonderland) and won the 31st Audio Drama Encouragement Prize. His play Backyard in RyCom won the Excellent Play Award in the 30th Yomiuri Theater Awards and was selected as a finalist for the 26th Tsuruya Nanboku Drama Award as well as the 67th Kishida Kunio Drama Award. It had a revival tour in 2024. In the same year, he presented Tattooer in Japan and the UK. Hanauri no en on (za) rain (The Fate of the Flower-seller: On(the)Line), which he wrote and co-directed, was a finalist for the 69th Kishida Kunio Drama Award.

In the second installment of our series, in which playwrights describe their own works, and the third article in our Okinawa feature, we introduce Backyard in RyCom, a provocative and engrossing work by Okinawa’s leading emerging playwright, Takuya Kaneshima. Tatsuki Hayashi, working at Naha Culture Arts Theater NAHArt, digs into the structure of Kaneshima’s world, which oscillates between past and present to deliver a visceral experience to the viewers and readers of the negative cycle in Okinawa. In turn, Kaneshima responds in-depth, as if reaching down to the rhizome.

Exploring Okinawa through the Performing Arts (1)

Exploring Okinawa through the Performing Arts (2)

Interview/text: Tatsuki Hayashi

English Translation: Hibiki Mizuno, Ben Cagan (Art Translators Collective)

-

Backyard in RyCom(2024 restaging) Playwright: Takuya Kaneshima Director: Maiko Tanaka Starring: Yuichiro Nakayama (left in photo), Issei Maeda, Takara Sakumoto (right in photo), Honami Kurashita, Gen Ogawa, Sei Kamida, Ryoko Gi, Michiko Ameku

May 24 to June 24, KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre: Medium Studio, ROHM Theatre Kyoto: South Hall, Kurume City Plaza: Kurumeza, Naha Cultural Arts Theatre Nahart: Small Theatre

ⓒ Nobuhiko Hikiji

Backyard in Rycom Premiere 2022

Synopsis

Asano, a magazine reporter, is assigned to investigate an incident in 1964 that saw the murder and injury of US soldiers in Okinawa, only to discover that one of the suspects was, in fact, his wife’s grandfather, Sakumoto. As he writes the article, having gone to Okinawa to continue the investigation, he eventually finds himself sucked into a mysterious place where Okinawa’s past and present are intertwined. Caught between Okinawa’s absurd past, which led to the murder, and the present demand to write an article that stands with the “brave Okinawan people who survived in the face of adversity,” Asano himself gets lost within the various norms surrounding Okinawa. To all viewers, the work begs the question: who is actually writing the story of Okinawa?

List of Characters

<Present>

Yuichiro Asano: A reporter for a culture magazine.

Chika Asano: Yuichiro’s wife and grandchild of Kanji Sakumoto; born in Futenma, Ginowan City.

Chinami Asano: Yuichiro and Chika’s daughter, who does not appear on stage.

Shuta Fujii: The editor-in-chief of the culture magazine and Asano’s boss He has feelings for Chie, and introduces Yuichiro to her.

Chie Irei: A baker in Yokohama who was born in Okinawa City. Her grandfather left behind memoirs and documents related to the killing and injury of the American soldiers.

Chie’s grandfather: He does not make an appearance on stage. In a photo taken in 1964, his face is identical to that of Yuichiro today.

Taxi driver: A mysterious taxi driver that picks up Yuichiro in Okinawa. He tells “Okinawa’s story” to Yuichiro.

Kinjo: A yuta (medium) in Okinawa who delivers a message from the deceased Kanji Sakumoto. He likes anpan (sweet red bean bread) and Coca-Cola.

<1964>

Kanji Sakumoto: Chika Asano’s grandfather and owner of a photo studio. Suspect in the killing and injury of American soldiers.

Takenobu Sakumoto: Kanji’s older brother and manager of a taxi company. He maintains a good relationship with the US military and is a member of a golf course exclusively for US military personnel.

Toyohisa Taira: A photographer at Kanji’s photo studio. Suspect in the killing and injury of American soldiers.

Shigemori Kakazu: Kanji’s childhood friend and employee at Takenobu’s taxi company. Suspect in the killing and injury of American soldiers.

Mamiko Sakae: Yoshikazu’s girlfriend, who testifies in the trial.

Taeko Oshiro: Owner of an oden restaurant frequented by the Sakumoto family.

-

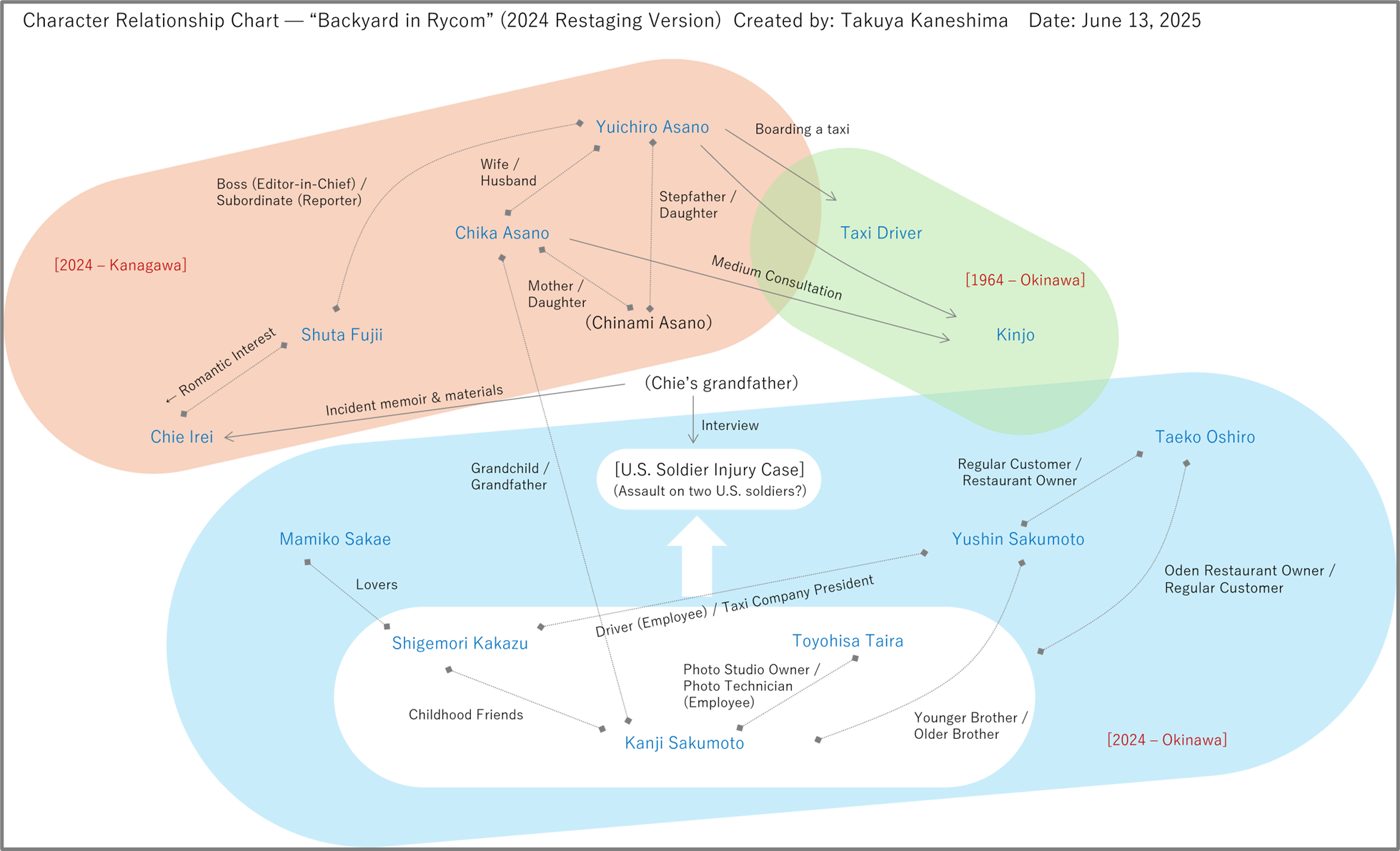

Character Relationship Chart for Backyard in Rycom (2024 Restaging), created by Takuya Kaneshima himself

Working in welfare, childcare, and theater

Born in Okinawa City in 1989, playwright Takuya Kaneshima has a unique background, having managed a kindergarten and served as the director of a shelter for women and children before becoming a full-time artist. His practice goes beyond theater, spanning radio dramas, essays, and novels. The work that led to his rapid rise is Backyard in RyCom, which won the Excellent Play Award in the 30th Yomiuri Theater Awards and was selected as a finalist for the 26th Tsuruya Nanboku Drama Award as well as the 67th Kishida Kunio Drama Award. His style of writing―which sheds light on societal structures by delivering incisive commentary through casual conversations and unapologetic language―is informed by a new method of theater making that questions the larger systems at hand, rather than seeing history and politics as a clash between good and evil.

- Okinawa holds a unique position within Japan. Could you start by touching on your upbringing and career before you became a theater maker?

- I was born in Okinawa City, which was formed through the merger of Koza City and Misato Village. Although I lived right near Kadena Air Base, I grew up without that much awareness of its presence in the area. My parents were lending the ground floor of our two-story house to an American military family while they also participated in protest movements against the bases, so I did see that position during my childhood, especially from my father.

I played baseball after school from elementary to high school, went to Ehime Prefecture for just a year during college, then transferred to Okinawa International University during my sophomore year to major in social welfare. I became interested in film and reading books around my senior year, but an older student recruited me to launch a company together. I casually agreed to it without much thought, which is how we ended up establishing a non-profit cram school. Since I had obtained my national certificate as a social worker, when I graduated university, we launched a cram school mainly aimed toward middle schoolers in orphanages. I continued that work for about eight years. Around the same time, I ended up taking over my mother’s kindergarten as well, so I was running both the cram school and the kindergarten [laughs].

Although I was caught up in my daily work, when I was 24 or 25, I started a theater company called chocodorobo (Chocolate Thief) with my friends in my high school baseball club that I used to make skits with. No one knew anything about theater, including myself, so we started by just figuring out basic things like how to write a script or which is left, and have continued like that to this day.

- At a certain point, you were juggling doing theater, running the kindergarten (up to 2024), and serving as the director of a shelter for women and children in Urasoe City.

- Both the kindergarten and the shelter for women and children are places that offer public welfare services, with standards and norms established by the welfare authorities. On the other hand, you have to ensure the freedom and agency of facility users and staff members from a managerial standpoint, which means preserving an appropriate distance to secure an internal buffer while responding to social demands. Put simply, that was the kind of work I was doing in welfare and childcare, and I feel that, in a nutshell, I do similar work as a theater maker. In other words, it’s about meeting the external demands of producers, audience members and so on, while upholding the integrity of internal factors like the characters and subject matter you are depicting. I always try to keep this duality in mind.

- Could you give a specific example?

- When I was commissioned by KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theater to create a work about Okinawa and presented Backyard in RyCom, for example, I felt that I was being asked to shed light on the historical disregard for the Okinawan people’s human rights, and to denounce the situation. On the other hand, some of my friends take a more pragmatic approach, saying that all we can do is take advantage of the current situation as much as possible to improve conditions for ourselves, while I have my own distinct views. In order to create a work to represent these circumstances, it’s necessary to maintain a certain distance from overly simplistic messages or feelings. I think this sense of maintaining distance is similar.

In my previous career, my role was to communicate with the administration while also listening to the voices of staff members and facility users. This meant taking in each opinion and not denying their positions, while also being clear when what they were asking for wasn’t possible. For better or worse, I adapted my behavior to suit whatever situation, and naturally learned how to speak persuasively. Maybe that’s why we were able to smoothly run things just during the years that I was in charge [laughs]. Although I don’t like how I try to overly adapt to please people, I also think this is an important ability.

Okinawa as Japan’s backyard

- So how would you describe Backyard in RyCom?

- It’s a work that depicts an actual incident that took place in Okinawa during the postwar US occupation, while also shedding light on the realities behind the military bases that remain today and the grinding down of quality of life and human rights. A line is drawn between Okinawa and the rest of Japan, with Okinawa forced to deal with these issues on its own. The work intentionally and blatantly exposes how the Okinawan people have unwittingly accepted this situation. I tried to clearly show the power at play behind the fact that I am writing and made to write this story, the forces that make me write this story, and the opposing dynamic between Okinawa and elsewhere. In a sense, I created this performance to provoke everyone, both the people inside and outside Okinawa.

The project is based on a book called Gyakuten (Reversal), by Chihiro Isa, which depicts the case of Okinawan citizens killing and injuring US soldiers in Futenma(*1), Ginowan City. It happened in 1964, when four young Okinawan men murdered an American soldier and seriously injured another, and the protagonist is a journalist investigating the incident in the present day, 2022. The plot centers on how one of the suspects turned out to be the grandfather of the journalist’s wife, and he finds himself sucked into the case as well as the time period. The timelines start to warp, with the story taking a turn towards science fiction and fantasy, depicting Okinawa today by going back and forth between its past and contemporary Japan.

- What’s the meaning behind the title?

- I really struggled to figure out the title. RyCom is an abbreviation of the Ryukyu Command Headquarters, which used to be occupied by the US military—it’s now turned into AEON MALL Okinawa Rycom. The name of the location, or what it was popularly known as, remained after the headquarters was reverted, and then RyCom was worked into the official name of the area when the Aeon Mall was constructed at the former US military golf court right near the headquarters. Since the name appears in Gyakuten as well, I thought it would be interesting to use it as a motif.

Then, as I kept writing the script, I started to feel that the word “backyard” was really apt in describing Okinawa’s position within Japan as a whole. At RyCom Aeon, there’s also a backyard where cardboard boxes and products are stocked, hidden behind the pleasant shopping area and invisible to customers. I thought it would be interesting to overlay the shopping mall structure onto the metaphor of Japan using the entirety of Okinawa as its military backyard in order to maintain its own comfort.

Keishi Nagatsuka, the artistic director of KAAT, also shared his impression of “RyCom” with me, saying that it hinted at something, even if you don’t know what it means. And then when you get curious and look into it, you discover that the name represents the two layers of postwar US occupation and Aeon Mall, one of the most representative large malls in Japan, so he encouraged me to use the name in the title.

The word “waiting” (included in the Japanese title, which is closer to “Waiting at RyCom”) is very useful and could refer to a wide range of grammatical objects, from the arrival of god to meeting up with a friend. In the context of this story, I think the question of who is waiting for what comes to the surface. Does it suggest that the people of Okinawa are waiting, with a certain sense of resignation, for the decision, action, and resolution from a “greater power”? Or perhaps the reverse, and they are waiting for a kind of hero figure to emerge? The word evokes the question: what are we waiting for?

-

The giant “Rycom” shopping mall (AEON Mall Okinawa Rycom) ⓒ Naoko Kitaue

- One thing that makes me think of is Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

- I thought people would make that connection. Although this is a kind of retroactive connection, Waiting for Godot is considered a masterpiece of Theatre of the Absurd. When reading and watching Beckett’s plays, though, I also feel like he’s actually depicting things that happen quite often. I think this sense of things that are absurd but actually not that unusual is directly connected to the situation Okinawa faces, as depicted in Backyard in RyCom. When you depict things about Okinawa, there’s inevitably some absurdity, but that absurdity is also commonplace. I do think there’s a link in that way.

- Another association that comes up, in contrast to the idea of “waiting,” is the fact that Japanese soldiers would die saying, “Let’s meet at Yasukuni,” (*2)to one another during the Asia-Pacific War. This phrase was also used in Okinawa, where a ground battle took place.

- Some of the civilian residents who died in Okinawa have been enshrined as “combat participants,” or military affiliates, along with war criminals. I believe that Yasukuni is a place that conveniently gathers the people who lost their lives due to the nation’s wars and political failures, as people who fought for the country. On the other hand, in Backyard in RyCom, RyCom is considered a place where data on the dead is gathered; casual, contemporary language is deliberately used to describe a place where the dead are archived in data form. Despite the fact that various places in Okinawa hold tragic memories of the war, that was all painted over by the US presence, which led to this place called RyCom.

This fact alone should be a tragic memory, but instead, the site has been flipped into a bright, bustling shopping mall, full of families and tourists. In a sense, the place is perpetrating violence in a really nonchalant way. In fact, I included the word Yasukuni a few times in the first draft of the script, but I ended up taking it out because I wasn’t able to incorporate it well enough. So although the literal word doesn’t come up, I do think that Yasukuni and RyCom are connected under the surface.

There’s also this funny anecdote, which may or may not be true, about how the older men and women of Okinawa would say, “you come, me come, RyCom,” to communicate with American soldiers when arranging to meet up. Since many young people in Okinawa don’t know the origin of the word, I’m hoping the title evokes many layers of images, including this “you come, RyCom” idea.

- ―In Backyard in RyCom, the present and the past are linked together, and various events from modern and historical Okinawa appear one after another. These include the 1879 Ryukyu Disposition and the surrender of Shuri Castle (*3), which ended the Ryukyu Kingdom’s 450-year-long history, as well as fact that the US military brought nuclear weapons and toxic munitions to Okinawa during the Vietnam War (*4).

The year 2022, when Backyard in RyCom premiered, marked 50 years since Okinawa’s “reversion” to Japan after US occupation (*5). Although this was advertised as the return to a peaceful, base-free island, today, about 70 percent of US military bases in Japan remain concentrated in Okinawa, which accounts for only 0.6 percent of the country’s total land. With the performance premiering in Yokohama, near Tokyo, during this critical year, did you intend to pack all of this history into the play and launch it back into the public consciousness? - Although I did have that intention, I myself wasn’t aware of the details of each event, of how they transpired, even if I knew vaguely about them. And once I started to learn about them, I realized that they all followed the same structure. Because they were repeating the same patterns, I felt it was necessary to describe all of them, to show that the same thing is still happening today. That’s why I tried to pack so much in, to not only show the fact that each of these things took place in the same way, but to give the audience an embodied experience by repeatedly showing it to them, as if dragging them around.

How to capture the words that pierce through

- In the 2024 revival tour, there was an online event for audience members across four regions to talk about their impressions. They shared many thoughts on the words that stuck with them, such as “It could’ve been anyone,” “the rule,” “yorisou” (standing with others), “backyard,” and “something like a horizon rather than a border.” The play contains many piercing phrases, and in the end, the protagonist is told, “Sacrifices need to be made somewhere in order to maintain the peacefulness of your everyday life.” Did you already have these words in mind before writing the script, or did they come to you as you were working on it?

- It can be both ways, but oftentimes I gradually find these words as I do my research, so it feels like I catch them rather than discover them within myself. It’s about how to best capture the words floating about in this world, not just in Okinawa. When I’m preparing the script, I often interview the characters. For example, I ask character A, whom I’ve created, about their background or how they feel about the case, and then I think and research about it, and craft their response to develop the character.

This exercise helps me gain more knowledge or develop my ideas, but it’s more that I’m taking in that person through my own body, rather than solidifying the character. If I can really sense the kind of person they are within myself—although this may sound a bit cultish—it feels like I create an empty space inside me that allows for the words that they might use to come together.

Because I was, in some sense, always doing that kind of work, with the word yorisou (to understand and show support for someone’s feelings), I didn’t really want to phrase it in a negative way that flips what I used to do. But I have to capture that sentiment, because that’s what my character A is feeling, and I’m able to draw out the duality by doing so. I depicted the uncomfortable feeling that comes up when someone uses the word “yorisou” to offer their support, because I find myself feeling that way. Maybe I’m able to find these words that cut through with different people because I base them on these kinds of things that I am reacting to myself.

- Do you feel a sense of guilt in using people’s pain and suffering, including moments in history, in your work?

- Yes, I do feel that way. For example, the phrase, “It could’ve been anyone,” was uttered by a man serving in the US military when he killed a young woman in Uruma City in 2016 (*6). Using the perpetrator’s words means that I’m also bringing the woman, the victim, on stage, so I’m questioning my own right to do such a thing. If I am going to use them, then, I have to take responsibility for that act; I need to really confront the weight of these words.

I myself am not always heavily opinionated about things that happen in this world or our society—I have vague thoughts about the kind of people or ideas out in the world, and in my writing, I try to explore how to capture something that pierces through this vagueness. So when I’m asked my opinion about things in everyday conversations, I often give a non-answer like, “Yeah, it’s hard to say” [laughs].

- At the same time, your work also carries a sense of humor and lightness.

- After all, I did start writing plays with my baseball club mindset, so it’s very easy for me to write cloudy conversations, and I think the challenge is about how to go back and forth between this cloudiness and the piercing words. I feel like the oscillation has a sharpening effect. When you start off with strong, heavy words, the accentuations and contrasts get dulled out, so instead, you softly plump it up, and pierce through it just when it’s about to burst. In terms of humor, I’m always hoping that people will laugh, but that’s not my main objective.

Of course, if it’s for chocodorobo, I’ll go for something more humorous, but when I’m asked to depict Okinawa, as in this case, it means highlighting the dark parts of history, so I think about how I can combine the different tools that I have, which leads me to using a sense of humor and lightness.

Creating a play that remains relevant a century down the line

- In the work, the act of writing itself serves as a theme, and Okinawa’s history is depicted as “a situation that has been trapped within the story.” Are there two approaches to storytelling—a repetitive style that follows, and thereby repeats, the narrative and established conventions, and another that deviates from them?

- I have a kind of tendency to thematize the act of writing itself. When it comes to history, we’re talking about writing left to us from the past, and records don’t live on unless someone keeps them. Even if it’s just a writer writing an article in the present moment, if someone from the future—say ten, 50, or even 100 years later—reads it, the article is then used to support or investigate historical events. A reconstruction of the kinds of lives and events that occurred takes place, so, as a writer, I do want to be conscious of the inevitable responsibility that comes with the act of writing something down.

In Backyard in RyCom, the story reveals that the protagonist himself was actually the writer of the narrative of Okinawa, of sacrifice. When you think about it, what remains as “history” is the history of those in power, of the victors. When we look at wartime and postwar literature, writers often contributed to creating the winners’ history. In contrast, in Backyard in RyCom, we see a grandfather’s memoir, which he refused to disclose to anyone. I think it’s important that he wrote it without the intent of having anyone read it, so I included that scene. In a way, it represents the history of the losers. And even if no one has read it to this day, as long as it remains, there’s a possibility that someone will discover it in the future. I think that’s the importance of writing things down—to show that we lived through these facts and experiences.

Even though these narratives don’t become part of the endless cycle of the victors’ history, maybe that’s what will lead to their discovery by someone who loses their way, down the line. That’s why I depicted both people who write things abiding by the narrative, and those who continue to write narratives that nobody reads. The last line in the play, “This isn’t to be read by anyone,” serves as convenient language for those in power, in the sense of discouraging people to read these narratives of sacrifice, but on the other hand, leaving something unread is also a way of bequeathing it to the future. I wanted to convey that duality through this line.

- The history of the winners repeats the same pattern, and the history of the losers isn’t read by anyone. I feel like your writing doesn’t fall under either category. How do you position your act of writing within this current reality?

- One of the interesting things about theater is how only a limited number of people can view it. Although only those who attended a performance experience the story, the text of the play remains. And then when people perform it a century later, it means that there’s this secret buried underground in the form of a play. I think there’s hope there, and something captivating.

By depicting the people who simply trace history—resigning themselves to thinking there’s no other way—from a bird’s eye view, Backyard in RyCom simultaneously shows the presence of those who make them abide by the rules. Preserving this duality within the play allows for those in the future to open up this vacuum-sealed package and understand what it was like back then, or arrive at interpretations suited to their own time. Theater is the easiest way to achieve that. Maybe that’s why I’m more particular about my script than my direction.

- As we delve further into this conversation, it’s really a shame to think about how the Kishida Kunio Drama Award wasn’t awarded to Backyard in RyCom. I’ve translated Elfriede Jelinek’s works in the past, and although the form of your output differs, I see many similarities between her works and yours. The first is that you both base your works on existing narratives, and respond to specific situations. Another is the diversity of language that you both use. At the same time, I also think that you have a fascinating characteristic that differs from Jelinek. While her works respond to various issues latent within the world, the land and history of Okinawa always run through yours.

And while your characters are individuals with feelings, at the same time, they are identified with the categories to which they belong. They become a person of the region, Japanese, or just one person who “could’ve been anyone.” Even though they have their own, real emotions, in some ways they are nothing more than their belonging to such categories. Although that’s the reality of all of us humans, we don’t usually have the opportunity to become aware of this simultaneity or duality. - I feel humbled to be compared to Jelinek, but I do think there’s something to be said about the idea of responding to things. In other words, the idea of responsibility contains the concept of responding. We can say this about our current reality as well as the original narrative that we base our works on, but I think one of the responsibilities we have as writers is to determine how to face things as they are, and show how to interpret them.

- I think there’s a lot of one-sided discourse nowadays, like the idea that foreigners should leave this country because it belongs to Japanese people, one that only views others in terms of their social category and finds comfort in belonging to a place through that metric, or the discourse that disregards categorizations and emphasizes universal human rights for each person as an individual. Even though it’s difficult for society to develop without considering both of these arguments, they never cross paths. You allow these two divided ways of thinking to coexist—even though it’s uncomfortable to read, I think it’s an important and interesting way of expressing this problem.

- I think it connects to the idea of authenticity, of being a stakeholder, of having a direct involvement in something. Because I am from Okinawa, people consider my work to be that of a stakeholder, but I don’t think that’s entirely right, in the sense that I didn’t experience Okinawa at the time. Although there’s a spectrum from stakeholder through to unconcerned party, you’re asked to determine which “side” you are on based on a single set of parameters. But you can’t always place yourself at one point, so I’m acutely aware of this sense of simultaneously existing at two points, and I don’t think we have rules that force us to place ourselves at a single point. I think we all have experienced having to juggle presenting one opinion to the world and internally harboring a different one. I always want to keep this duality in mind while writing my plays.

-

the case of Okinawan citizens killing and injuring US soldiers in Futenma

On August 16, 1964, during the US occupation, two US soldiers and four young Okinawan men (two of whom were from Tokunoshima) got into a brawl in the restaurant district of Futenma, Ginowan City, resulting in the death of one US soldier and serious injuries to the other. The four youths were charged with manslaughter in a US civil court, and the case was deliberated by a jury of mainly Americans. Although Okinawan jury member Chihiro Isa convinced the jury to acquit them of manslaughter, three of the young men were sentenced to three years in prison for assault and battery.

-

“Let’s meet at Yasukuni,”

During the Asia-Pacific War, this phrase was used by soldiers in the Imperial Japanese Army when heading to the front, or when unlikely to return home alive due to suicide missions. It was used to mean that if they were to die in war, they would be reunited as spirits of fallen heroes at Yasukuni Shrine, which was enshrined in 1869 by the Meiji Government under the initiative of the Meiji Emperor as Tokyo Shoko Shrine, and renamed in 1879. It enshrines as deities “national martyrs” who died in support of the emperor in political and civil warfare from 1853 onwards—during the final years of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the subsequent Meiji Restoration—as well as those who fell in foreign wars, including military personnel and civilians.

-

Ryukyu Disposition and the surrender of Shuri Castle

The Ryukyu Disposition refers to the process by which the Meiji Government demanded that the Ryukyu Kingdom abolish its tributary relationship with Qing China, and used the threat of military power to integrate the kingdom into Japan. In 1872, the government first placed the Ryukyu Kingdom under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as the Ryukyu Domain, before abolishing the Ryukyu Domain in 1879 and establishing Okinawa Prefecture. The Ryukyu king was expelled from Shuri Castle and ordered to settle in Tokyo, marking the end of the Ryukyu Kingdom.

-

the US military brought nuclear weapons and toxic munitions to Okinawa during the Vietnam War

During the Vietnam War, Okinawa was ruled by the US administration and used as a base from which American soldiers went into the warzone. Toxic munitions were also brought into Okinawa, and in July 1969, a poison gas leak took place in Kadena Air Base, resulting in the hospitalization of 24 US soldiers. US media reported on the incident and revealed the presence of toxic munitions, which led to a movement calling for their removal.

-

Okinawa’s “reversion” to Japan after US occupation

Although Okinawa was under US rule for many years after the Asia-Pacific War, it was returned to the Japanese government on May 15, 1972.

-

a man serving in the US military when he killed a young woman in Uruma City in 2016

On April 28, 2016, a 20-year-old woman went missing while taking a walk in Uruma City, Okinawa Prefecture, and she was found dead in the woods of Onna Village on May 19. An investigation led to the arrest of a former US military employee, who was charged with murder and rape resulting in death. He was sentenced to life imprisonment in 2017.

-

Special Thanks to: Naha Cultural Arts Theater NAHArt, KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre

Related Tags