Hisashi Shimoyama / Tomoya Ogoshi / Shouichi Touyama

Exploring Okinawa through the Performing Arts (1): Himeyuri Peace Hall, Garaman Hall, and Mekaru Base

Photo: Naoko Kitaue

An independent state from the fifteenth to nineteenth centuries—known as the Ryukyu Kingdom—Okinawa still retains its own unique traditions and culture, having been incorporated into Japan in the modern era. It was the site of a brutal land battle in World War II, and was then placed under American control after hostilities ceased, before its reversion to Japan in 1972. Its development has continued even while hosting vast US military bases, and various arts and cultural facilities have been established since the turn of the twenty-first century.

This feature introduces the hall of the Himeyuri Alumnae Building, now overseen by a seasoned producer with over half a century of experience presenting controversial works from Okinawa, to a city-run cultural complex in Naha that includes both small and large theaters and opened its doors during the COVID-19 pandemic. It comprises interviews with key figures involved in running five theaters and halls that have opened since 2000; a column introducing essential cultural spots in the region; and a deep dive into the work and life of Takuya Kaneshima, a leading Okinawan playwright born in the Heisei era. We will explore the latest in Okinawa’s performing arts scene over three installments, each from a different perspective.

The first article features the “faces,” or presenters, who run three of the five theaters and halls. (See the second article here.)

Interview/text: Junichi Maeshiro

English Translation: Hibiki Mizuno, Ben Cagan (Art Translators Collective)

① Himeyuri Peace Hall

-

Himeyuri Peace Hall

388-1 Asato, Naha City, Okinawa Himeyuri Alumni Hall 2F

Opened: 2017

Seating capacity: Approx. 80 seats

The Sakaemachi Arcade1 is an area still reminiscent of Okinawa’s post-war reconstruction, but before the war, this was where the school of the Himeyuri Student Corps2 used to stand. On the second floor of the Himeyuri Alumnae Building—established as a hub to promote peace by fellow students who survived the war—there is a small theater called Himeyuri Peace Hall. This is where Hisashi Shimoyama, leader of ACO Okinawa—a group that has been staging performances around the theme of Okinawa and peacebuilding for the last 50 years or so—has been working since 2021.

- Can you tell us about what makes the theater special?

- This is where the Himeyuri alumnae used to gather, but during the coronavirus pandemic they offered us the use of the space, and so we decided to move our headquarters here in 2021. Operating within the Himeyuri Alumnae Building has made us more aware of how important it is to not just present performances, but deliver multilayered stories about peace. With the theater carrying the name of Himeyuri, and the program featuring works that grapple with issues that directly relate to the Battle of Okinawa and our world today, I would say there’s probably no other place like this in Okinawa.

As an aside, the Himeyuri alumnae still gather twice a month to sing songs together, and about five of them will be turning 97 this year. They sing elementary school songs and other pieces that they didn’t get to sing for their graduation. Listening to them sing is a very healing and encouraging experience. They also never miss our shows.

-

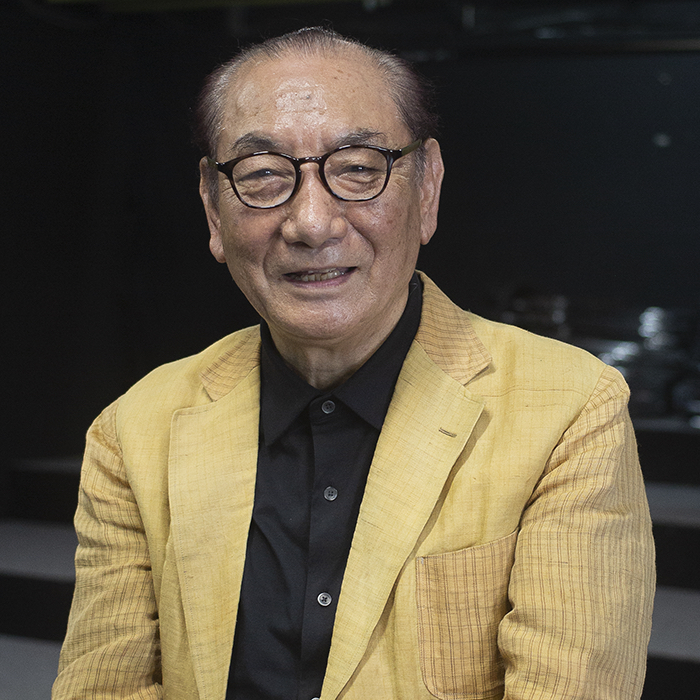

Hisashi Shimoyama

- How do you feel about presenting works from Okinawa?

- I was born in Tokyo, and decided to move to Okinawa upon my first visit right after its reversion to Japan3. Since this place is the most immediately and directly affected by any changes to the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty or the Japan-U.S. Status of Forces Agreement4, I felt that the situation faced by Japan as a whole was particularly salient in Okinawa. I thought that we could convey the current realities of Japan by presenting works from Okinawa, a place that is confronting these issues head-on.

When it comes to the topic of war, Hiroshima and Nagasaki are well-known for the atomic bombings, but there is much less awareness throughout Japan concerning the Battle of Okinawa. Considering this situation, I’ve explored ways to leave a strong impression with our works, whether it be staging Gama in an actual gama5, or creating a piece on Okinawa’s postwar history that integrates the region’s songs and dances. There’s a work in our repertoire called Shima Kuduchi, which means “speaking of the island,” and it originally premiered in Tokyo in 1979. Although the piece was made 40 years ago, it hasn’t aged at all, which I feel also shows how the situation in Okinawa hasn’t changed.

-

Shima Kuduchi (2019) ⒸACO Okinawa

- Your performances have also been shown widely on the mainland of Japan to critical acclaim. What are some of the challenges you face going forward?

- Since the majority of our audience members are of an older generation, it’s been difficult to increase the number of younger attendees. I’m sure it’s a similar situation in Tokyo, but especially with the evening performances, most people who work can’t attend them, so that’s a challenge. I also believe that one of theater’s important roles is to share our performances with many people, so I would really like to create a system to consistently present works in Tokyo, given how highly populated it is, but figuring out the travel fees and selling tickets is another big hurdle for us.

- What kind of theater do you aim to create?

- We want to continue creating works for the local community, and also tour to other regions to foster a space of mutual learning around the situation that Okinawa and Japan face. My hope is to create a theater space that connects us with the audience and gives us the vitality and courage to keep leading our lives.

-

Sakaemachi Arcade

Sakaemachi Arcade is a market located in Naha City’s Asato. During the day, it caters to locals as a shopping area lined with grocery and home goods stores, while at night it transforms into a pub district frequented by people from inside and outside the prefecture. Originally a black market that sporadically developed from the burned-out ruins of the Battle of Okinawa, it is known for its distinct Showa-era atmosphere, including its maze-like structure that came out of repeated extensions. Sakaemaechi is the colloquial name of the market, and not the official address of the location.

-

Himeyuri Student Corps

The Himeyuri Student Corps refers to a group of female students from Okinawa Shihan Women’s School and Okinawa Daiichi Women’s High School who were primarily mobilized as a nursing unit to the battlefields of Okinawa during the ground attacks of World War II. The women’s student unit has been the subject of various works of literature, manga, and cinema.

-

Reversion to Japan

Okinawa Prefecture, which was ruled by the US under a peace treaty signed with Japan upon its defeat in World War II, reverted to Japan on May 15, 1972. Invaded as a landing point during the war, Okinawa ended the War under American military occupation and remained under US jurisdiction for 27 years.

-

The Japan-U.S. Security Treaty or the Japan-U.S. Status of Forces Agreement

The Japan-U.S. Security Treaty and the Japan–U.S. Status of Forces Agreement are officially known as the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between Japan and the United States of America. This Treaty permits the presence of US military bases on Japanese soil in order to ensure the security of both nations.

-

Gama

Gama refers to natural caves in Okinawan. During the Battle of Okinawa, gama were used as evacuation points by local residents and Japanese soldiers and as field hospitals to shelter from air raids. As many civilians were forced to commit suicide using hand grenades and poison to avoid becoming prisoners of war or burned by flamethrowers inside these caves, the gama have become one of the most-visited category of war sites in peace education tours. They were also used for the mortuary practice of fuso, or open-air burial, up to the Meiji period.

② Garaman Hall (Ginoza Village Culture Center)

-

Garaman Hall (Ginoza Village Culture Center)

314-1 Ginoza, Ginoza Village, Kunigami District, Okinawa

Opened: 2003

Seating capacity: Approx. 406 seats

Located in a small village called Ginoza, Garaman Hall is a modest venue that presents a wide range of programs, inviting internationally renowned artists and showcasing regional art forms strongly rooted within the community. In this interview with Tomoya Ogoshi, the theater’s Chief Director, we discuss the venue’s approach to working with the local community, lessons learned surviving the pandemic, and more.

- I would first like to ask about Garaman Hall and its unique location in Ginoza. Your programming also feels quite distinct.

- After opening in 2003, the hall was operated by village officials for the first two years. I started my position there in its third year and have been running the space through trial and error ever since. Even though the village has a small population of 6,000, each ward has a well-run community center—something quite rare in Japan. So most of the time, people rent out those spaces. In other words, local residents don’t use our venue unless they really have to.

So when I first took up this position, I invited many people from outside of the community. At one point we garnered a lot of attention for bringing cutting-edge jazz musicians, and we made quite a name for ourselves after five or six years, but about 80 percent of the attendees were always from outside of the village. I began to question this situation and, just as I was seriously reconsidering our next steps to give back to the local community, we entered the pandemic.

-

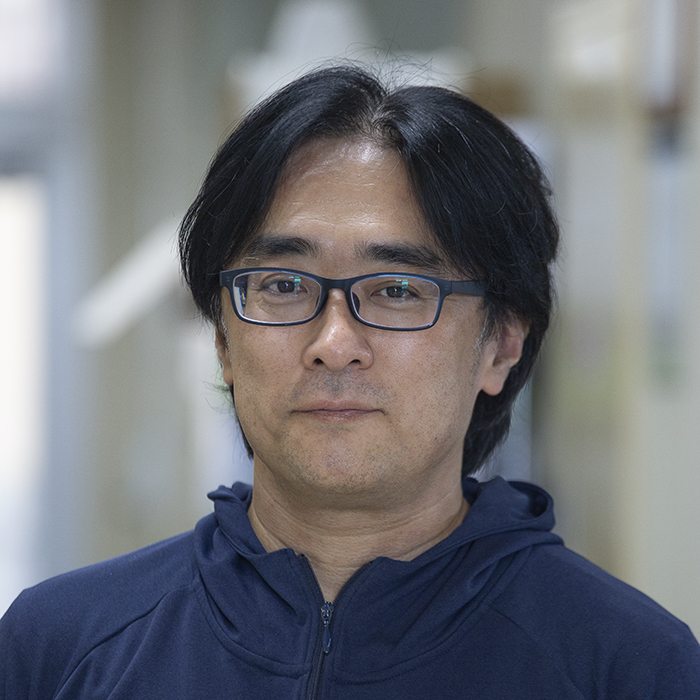

Tomoya Ogoshi

- Theaters across Japan faced many difficulties during the pandemic—how did Garaman Hall deal with the situation?

- Many theaters started streaming their content, but we don’t have any video equipment besides a projector. What we did have though was time, so we explored many ways to promote our theater, learning all the while. We tried to do some live streams as well, but in the end, we ended up making a film. It’s a documentary called UMUI — Guardians of Traditions (2023, directed by Daniel López), which follows the daily lives of people who work in the local traditional arts. The word “umui” in the title means “feeling” in Okinawan. In 2023, the piece was nominated for the Nippon Connection Film Festival, the EU’s largest Japanese film event annually held in Germany, so we attended the festival and presented a post-screening dance performance, and we received a lot of positive feedback.

-

Film UMUI × Stage Performance

A performance featuring traditional arts on stage after the screening of UMUI.

- As a local endeavor, it feels really crucial for the theater to highlight and promote the arts that have close ties to people’s daily lives.

- We learned a lot making UMUI. While there’s an increasingly wide range of options available for children, Ryukyu dance remains a bit daunting to learn. At the same time, this region still carries the tradition of Honen festivals6, and the custom of performing traditional arts to celebrate the harvest moon (the fifteenth night of the eighth month, according to the lunar calendar), so local children are familiar with the performing arts. With that in mind, we explored the question of how to approach and promote regional arts and cultural resources through the film.

-

Honen festivals

Honen festivals are held at each village ward to pray for bountiful harvests. Primarily run by villagers associated with youth groups, various forms of art including shishimai, eisa, kumiodori, and bojutsu are performed as ceremonial offerings. Although gradually simplified year by year, these harvest festivals are still held in Ginoza, as well as other villages and small islands, representing the close ties between the arts and people’s everyday lives.

- As a theater committed to its local community, how do you build relationships with the villagers?

- As an outsider, five to six years is really not enough time at all to run a theater and foster relationships with the community. It’s only after 10 years or so that you’re able to nurture talent and build deeper ties with the younger generation entering society, and so on. Just working with your own generation doesn’t lead to more growth or change. For example, our staff photographer, who also handles our flyers, was a high schooler when we first met.

He was originally playing in a band and began to connect with various artists through our venue, which influenced his perspective. It’s important to take a time span of 10, 15 years when looking at the cost-effectiveness of investing in culture and the arts. We’ve been able to connect with the locals in these ways, but theaters are still considered highbrow, so we need to actively branch out in order to build ties with different people. This is why we host a range of events from other worlds, like food festivals, to showcase the performing arts and build connections.

- What kind of vision do you have for Garaman Hall in the future?

- There are certain forms of culture that have remained or been preserved because of the unique qualities of this region. It’s nice for local people to have opportunities to be reminded of these things, and if the culture is presented to and embraced by the outside world, they can feel a sense of pride as well. I believe that the power of Okinawa’s arts lies in the fact that they have tangible and close ties to the people’s lives—there are everyday people, maybe a public official or a local farmer, who can still play the sanshin. We want to embrace that in how we run the theater.

At the same time, we hope to present new perspectives through things like combining a local creative eisa group with contemporary dance, or Ryukyu dance with animation. I feel that it’s important for theaters today to also commit to trying out new things while honoring the regional culture.

③ Mekaru Base

-

Mekaru Base

203 Mekaru, Naha City, Okinawa

Opened: 2017

Seating capacity: 74 chairs / Max 100 seats

Mekaru Base is a small private theater, a rare presence in Okinawa. While the theater focuses on presenting contemporary pieces from inside and outside the prefecture, in recent years, it has been actively expanding beyond theater and into fields including comedy, music, and art. The space is run by Shouichi Touyama, who works on the performances as an actor, director, writer, lighting designer, sound designer, and producer.

- How would you describe Mekaru Base as a theater?

- The most distinct thing about Mekaru Base is that it is a privately-run theater. This means that we don’t have to abide by the Designated Administrator System, so we don’t have to be so strict in how we use the space. For example, audience members can eat and drink inside, and directors can freely change the way they use the seats. Since I’ve also struggled in the past with all of the regulations when renting out a public hall, we try to keep the rules lax to accommodate the organizer’s vision as much as possible, to try and not have specific restrictions. It’s a space where people can let their imaginations run wild, not just with plays, but with all kinds of genres—even solo exhibitions, for example.

On top of that, there’s a living room and tatami room above the theater, so collaborating company members can stay there. They can use the area for rehearsals and cooking meals as well, so we open up the space for people who come from outside of Okinawa.

-

Shouichi Touyama

-

Uchikabi ⓒGekishoku Otonadan

-

Nine Stray Okinawans ⓒGekishoku Otonadan

- Are there any local considerations you keep in mind when promoting theater in Okinawa?

- I lead a theater group of working adults called Gekishoku Otonadan, and there we try to create works that can only be made in Okinawa, that are particular to this place. We have works like Uchikabi7, which is about our culture and customs, and Nine Stray Okinawans8, which features conversations about the complex reality of Okinawan society. When we present the performances outside of the prefecture, we intentionally leave out translations for the Uchinaaguchi, or the Okinawan language, that the actors use. I feel that this represents the spirit of doing regional theater, away from the center (Tokyo), that this is what it means to put something out that could only come from here.

-

Uchikabi

Uchikabi is a piece written by Gakuji Awa and directed by Shouichi Touyama. The word “uchikabi” refers to “money for heaven,” used to entertain ancestral spirits during traditional annual events in Okinawa. Originating from China, it is a custom in which people burn money as an offering so that their ancestors have financial stability in the afterlife.

-

Nine Stray Okinawans

Nine Stray Okinawans is a piece written by Gakuji Awa and Seiichiro Kuniyoshi and directed by Shouichi Touyama. Just before the 1972 reversion of Okinawa to Japan, nine people—including a research expert, a housewife, a war survivor, and a mainlander—gather in one room to talk about their thoughts on Okinawa based on their respective positions and experiences.

- It seems really crucial to incorporate the significance of expressing something locally in Okinawa. As a theater space, how do you develop relationships with the local community?

- I feel like it’s often the case that locals find theater spaces to be suspicious [laughs]. They often have this impression that some strange-looking people go in and out of the place, so I’ve made an effort to properly greet the neighbors and let them know that we’re not “weird.” We also host an annual mochitsuki (rice-cake making) event for New Year’s and serve otoso (spiced sake). I was happy to have some kids join us after we promoted it on social media.

Since I set up all of the theater’s stage machinery, lighting, and sound, I also try to help local high school students in theater clubs or young industry professionals by offering production advice. I visited various theaters across the country before opening this space and learned that it’s essential to carry a sense of hospitality as a theater rooted in its locality. Of course, it can be hard to maintain, but it’s also what makes running a space enjoyable. It’s nice when people want to stop by just because they find it interesting, and especially when it’s a local place, you can foster a really positive relationship when people come together.

- I can see how it’s ideal to create a space where locals can casually gather. Considering these aspects, what are some things you hope to achieve with the theater going forward?

- I hope that we can create a space that allows for all kinds of creative experimentation, going beyond theater performances. We also want to work with artists who can explore different ways of using the space outside of the theater context. I’m hoping we can invite theater companies from outside of Okinawa and get more people to attend our shows, while also relaunching our artist-in-residency program.

-

-

Residence Space – Japanese-style Room 1

- In “Exploring Okinawa through the Performing Arts (2),” venues ④ National Theatre Okinawa and ⑤ Naha Cultural Arts Theater NAHArt are introduced, along with cultural spots ⑥–⑫ (see map below).

Okinawa Series – Map of All Featured Locations

① Himeyuri Peace Hall; ② Garaman Hall; ③ Mekaru Base; ④ National Theatre Okinawa; ⑤ Naha Cultural Arts Theater NAHArt; ⑥ Sakima Art Museum; ⑦ Rycom (AEON Mall Okinawa); ⑧ Theater Donut Okinawa; ⑨ Roadside Station Kadena; ⑩ Sakurazaka Theater; ⑪ Okinawa Prefectural Library; ⑫Junkudo Bookstore – Naha

Photo: Naoko Kitaue

Hisashi Shimoyama

As the leader of ACO Okinawa, Hisashi Shimoyama has planned and produced many original performances on Okinawa and its regional traditional art forms. In 1994, he launched the International Theater Festival Okinawa for Young Audiences, or ricca ricca festa, as its general producer and artistic director, which was awarded a 2019 Japan Foundation Prize for Global Citizenship. Building networks with artists and festivals at home and abroad, he has created numerous international collaborative works with artists around the world as well. In 2021, he served as the general producer and artistic director of the 20th ASSITEJ World Congress, which was held in Japan for the first time. He has dedicated his career to connecting the Japanese and international theater scenes and presenting quality performing arts to children. He is the recipient of many awards, including the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology’s Art Encouragement Prize, and is an Honorary Member of ASSITEJ International.

Photo: Naoko Kitaue

Tomoya Ogoshi

Born in Hiroshima Prefecture, Tomoya Ogoshi studied music education and theory at the University of the Ryukyus and was commissioned as the General Manager of Garaman Hall (Ginoza Village Culture Center) in 2005. Involved in numerous projects that connect regional cultural resources and the performing arts, he has produced an array of concerts, theater performances, films, workshops, and art exhibitions. In recent years, he has promoted cultural exchange at home and abroad through producing and screening the documentary film UMUI — Guardians of Traditions, and received the Japan Association for Arts Management Award in 2024. Managing all aspects of operations from planning, production, and promotion to technical coordination, he explores sustainable ways of creating art rooted in the local cultural scene.

Photo: Naoko Kitaue

Shouichi Touyama

Having acted in various performances such as Most Valuable Player: The Jackie Robinson Story (written and directed by Mary Hall Surface) and The Winds of God (written by Masayuki Imai and directed by Tatsunosuke Takatou and others) as part of Theater Seigei in Tokyo, Shouichi Touyama moved to Okinawa in 2004 and has been based there ever since. After acting and producing performances for AOC Okinawa, he founded Gekishoku Otonadan in 2011. In 2015, he established the Okinawa Art Culture Theater, a general incorporated association that supports small theaters, followed by Mekaru Base in 2017. While continuing his acting and directing career with works such as Konsui [Coma] (2021, written and directed by Tomoyuki Nagayama as Theater Company Cofuku Gekijo’s 30th anniversary performance), he also serves as the chairman of the Smaller Theatre Initiative and dedicates his practice to further enriching Okinawa’s theater industry. In addition, in July 2025, he launched the Mekaru Base Theatre Laboratory, beginning new efforts to foster and train the next generation of performers.