Takuya Kato

Playwrights’ Guide to their Own Works Vol. 1 ー Takuya Kato on Dodo’s Free Fall

Photo: Atsuharu Ino

Photo: Atsuharu Ino

Takuya Kato

Born in Osaka in 1993, Kato is a playwright, director, and leader of Takumi Theater Company. He began writing for radio at the age of seventeen, and at eighteen he went to Italy to study film directing. After returning to Japan, he founded Takumi Theater Company. He has been involved in many plays outside his own theater company, writes for TV dramas and both writes and directs film. In 2023, Kato had his first overseas production in Taiwan with Watako’s Entanglement. In 2024, his newly written work One Small Step was staged at Charing Cross Theatre in London. In 2021, he won the 10th Shinichi Ichikawa Script Drama Award for Kirei no Kuni (NHK). In 2022, he won Best Director at the 30th Yomiuri Theater Awards for Mohaya Shizuka and The Welkin. In 2023, Dodo’s Free Fall won the 67th Kishida Kunio Drama Award, and his film Hotsureru won the 45th Nantes Three Continents Film Festival Distribution Support Award. In the same year, he was selected for Forbes Japan 30 Under 30.(Updated February 2025)

https://www.web-foster.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/TakuyaKatoBiography.202409.pdf

With the spread of initiatives such as the Eternal Performing Archives and Digital Theatre (EPAD) and STAGE BEYOND BORDERS (SBB), there are more opportunities to watch Japanese plays with subtitles in several languages. However, to fully grasp the vivid linguistic landscape shaped by unique cultural contexts and daily customs, where many proper nouns are exchanged, additional information and support beyond subtitles would be helpful. In response to this need, we are beginning a series where the playwright provides direct insights into their work. By asking direct, basic and specific questions, we hope to uncover the background and structure of the plays, allowing their deeper meanings to emerge. It’s a guide for all people interested in the playwright’s work, whether they have seen it or not, and whether they speak Japanese or another language.

For the first article, we welcome Takuya Kato. He answered questions from critic and dramaturg Kenta Yamazaki about his acclaimed play, Dodo’s Free Fall (original version).

Interview/Text: Kenta Yamazaki

English Translation: Claire Tanaka

Dodo’s Free Fall (original version)

Playwright/Director: Takuya Kato Starring: Kisetsu Fujiwara, Tetsu Hirahara, Ryutaro Akimoto, Takenori Kaneko, Takafumi Imai, Kyuichiro Nakayama, Mari Yasukawa, Yuni Akino, Tatsuya Yamawaki

September 21 to October 23, KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre: Large Studio, Sapporo Cultural Arts Theater hitaru Creative Studio, Matsumoto Performing Arts Centre

Distributed in a joint project of EPAD and the Japan Foundation

Synopsis (from the Takumi Website)

Shinya, who works at an event production company, and Shoda, a comedian, receive an unexpected phone call from their fellow comedian friend Natsume. Three years before, Natsume had phoned Shinya and other friends to say he was going to jump to his death and they lost contact with him after that. But two years later Shinya is contacted by Natsume again. Natsume says that he had stayed in a hospital run by the police for “reasons” and then goes on to explain those reasons. After that, Shinya and his friends get together with Natsume again, but the “reasons” have changed the relationship between Natsume and the others. A three-year tale of disappearance and recklessness, following the intertwined lives of Shinya, Natsume, and their friends.

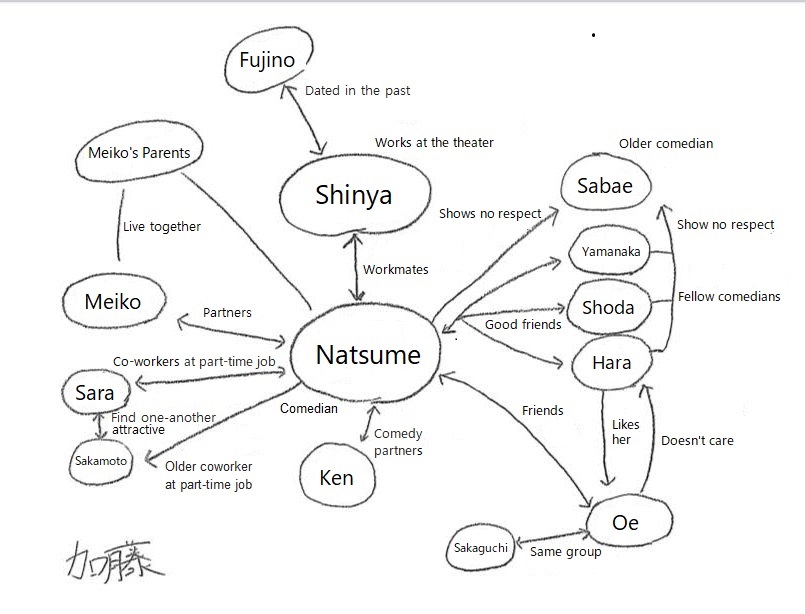

Characters

Shinya: (Male) Works at a small-scale event production company and concert venue. A coworker and friend of Natsume.

Natsume: (Male) Comedian. Hides the fact that he has schizophrenia while working as a comedian.

Shoda: (Male) Younger comedian than Natsume, but almost his peer. Has a part time job at the same place as Natsume.

Yamanaka: (Male) Broadcast writer. A friend of Natsume and the others.

Sabae: (Male) An older comedian in Natsume’s circle. Natsume and the others don’t take him seriously.

Hara: (Male) A comedian who debuted at the same time as Natsume. Likes Oe.

Oe: (Female) An underground idol.1 Seems to like Natsume.

Fujino: (Female) Was Shinya’s girlfriend until she broke up with him. Might be trying to get back together with him.

Blue Demon: (Female) Gets picked up by Natsume and the others at an izakaya with communal seating. Blue Demon (Ao Oni) is a nickname that Natsume and the others gave her.

Meiko: (Female) Natsume’s wife. Lives with Natsume at her parents’ house.

Sara: (Female) A 19-year-old who works at the same part-time job as Natsume. Has a bit of interest in Sakamoto.

Sakamoto: (Male) Leader at Natsume’s part-time job. Has a bit of interest in Sara. Hard on Natsume.

-

Takuya Kato’s handmade character relationship chart for Dodo’s Free Fall (original version)

A Title Inspired by a Bird Driven to Extinction by Humans

Takuya Kato began his career writing scripts for radio at the young age of seventeen before expanding his practice to the fields of theater and film. His works, sometimes driven by strikingly naturalistic dialogue and other times set in speculative fiction, vividly capture the complexities of human behavior beyond rational explanation. Regardless of genre, he crafts narratives that probe the essence of humanity and pose thought-provoking questions without easy answers. Dodo’s Free Fall, winner of the 67th Kishida Kunio Drama Award where it was praised by several members of the judging committee for its highly realistic script, is one such work.

- First, I’d like to hear it from the writer himself. What sort of play is Dodo’s Free Fall?

- The original version of Dodo’s Free Fall is made up of two stories that intersect. The first follows Natsume, a comedian who has been concealing his schizophrenia, until one day when his secret is suddenly exposed, causing him to gradually find himself alienated from those around him. The other story centers on his friend Shinya, who, when Natsume keeps saying he’s going to die, begins constantly keeping an eye on him in an effort to keep him alive.

I actually wrote Dodo’s Free Fall based on a personal experience. I had a comedian friend whom I had known for years before realizing he had schizophrenia. One day when we were hanging out, he suddenly started talking about how he could hear voices and became agitated, and the things he said didn’t make sense. I wasn’t sure what was going on but I figured since he was an entertainer, he was in the habit of putting on a show for people and fooling around, so I processed it as an extension of that. After that, he’d sometimes contact me and tell me he was about to die, or he’d start acting strange when we were hanging out. I was worried about him so I met with him more often, but one day he cut contact with me completely.

Then, after a while I heard from a mutual comedian friend that he was in the hospital for schizophrenia, and that was how I found out he was ill. About two years later, he reached out to me after his symptoms had settled down, and we met again for the first time in a long while. We talked about the time when he was having symptoms and what he had been doing while we didn’t see each other. Meeting my friend after such a long time, I found myself thinking, “What did I find so funny before?” When I thought about why I no longer found him funny, I thought one reason was because the illness was like a filter. When I didn’t know he was ill, I engaged with his symptoms seriously, and when I met him again, he had quit being a comedian, so I thought that might have had an influence. I thought maybe if he had continued to be a comedian I would have been able to continue laughing. In a sense his position as a comedian legitimized him as a person to laugh at. Or I think it was a way for him and the people around him to legitimize laughing at him. In other words, maybe his career as a comedian gave him a way to connect with society and the people around him.

The reason I put the name of a bird that was made extinct by humans, the dodo, in the title was because it overlapped with the protagonist, Natsume’s image. Even a bird doesn’t want to fly if it doesn’t have to. A bird that can’t fly due to human intervention and has no choice but to fly to escape is an image that overlaps with Natsume having to continue to be in society. I think the title Dodo’s Free Fall is a way of indicating what sort of story it is.

What is the Underground Comedy Industry?

- Many of the characters in this work are comedians. Could you explain a little about the type of people in the story and about Japan’s comedian culture?

- The story is set against the backdrop of Japan’s entertainment industry, known for its insular and hierarchical relationships—something that might be difficult for international audiences to grasp. But on the other hand, I don’t think the individual characters are particularly unusual individuals. It goes without saying, but each person has different ways of communicating, and in that sense, Natsume and the others aren’t so different from people outside the comedy industry. Just like how start-ups have their own start-up culture, every industry has a certain life rhythm that everyone with the same job develops and they start hanging out together and that sort of insular culture happens naturally. I think the natural atmosphere that comes about in this work is more like that of the underground comedy industry than the one you find in television or famous theaters. But the fact that they call themselves comedians and make that known causes the people around them to respond and react differently.

I think most people in Japan are familiar with the sorts of comedians that appear on TV variety shows. But Natsume and the others are the type who are performing at little theaters and paying for their own ticket quotas. Some of the people who start there get a chance to appear on television and begin to make real money at it, but people who aren’t getting those television appearances still have ways of making a living in the industry. There are options like eigyo (performing at events),yose,2 organizing their own events, and so on. In Japan, making a living as a comedian does not necessarily require frequent television appearances. The premise in the play is that Natsume has to work a side job in addition to doing comedy. The people Natsume hangs out with sometimes see their behavior as comedy practice, while other times they simply want to be popular or to be liked by people they admire, and as a result those elements overlap when they are all just trying to create a lively atmosphere. They try to turn little private incidents into comedy bits, and they think it is good to do so. There are probably several reasons for that.

-

underground idol

An indies-type idol entertainer who holds concerts and events that aren’t covered by mainstream media.

-

yose

Yose are theaters that specialize in popular entertainment like rakugo and other storytelling, music, and magic acts.

Comedy and Compliance: Perspectives of those with or without Lived Experience

- During the play, there are several scenes depicting how the comedic atmosphere sometimes results in harmful behavior. One such scene takes place at an aiseki izakaya—a type of Japanese bar where strangers are seated together. Natsume and his friends invite a woman they nickname Blue Demon to karaoke, only for her to find a large group of comedians already waiting there. The realism of the scene made it all the more unsettling to watch.

- There is a prevailing idea that anything that happens in private life can be turned into material for comedy, creating a culture where boundaries are blurred. I don’t agree with it, but there has long been a belief that “everything is fuel for art.” I’m sure that sometimes results in harassment and harm. I think there is a fundamental misunderstanding about how personal experiences should be transformed into creative energy.

As a closed-off industry overall, I think it’s hard to address issues. It’s not just about the entertainment industry. I think it’s the same in other isolated cultural communities. By defining themselves through rigid categories like “industry” or “scene,” these groups may reinforce a sense of distorted solidarity.

- What was the audience reaction when it premiered?

- A lot of people said they weren’t sure whether they should laugh or not. They would start out laughing but once they realized Natsume was ill, they would become unsure how to take his behavior. I wrote this work because I wanted audiences to experience the same change in feeling that I had experienced, so to some extent, it achieved its goal.

I have a hard time giving a clear answer to the question of whether they should laugh or not. Natsume himself wants people to laugh. That doesn’t change just because he is ill. But the way he is perceived by those around him changes. That is an issue of the relationships between people with mental illness and people without. It often happens that people who are not affected act with the intention that they understand a person’s feelings, but as a result they respond in ways that are far removed from what that person wants.

- Still, setting aside what Natsume himself wants, I think one must consider whether it is okay to laugh at someone who is ill. In media like television variety programs that have the power to influence a lot of people, it’s an issue that has to be taken even more seriously. When someone with a specific illness or a member of a minority group is made to be the target of comedy, there’s a risk of making other members of that group targets of discrimination.

- To claim that people with illnesses or minority identities shouldn’t become comedians would itself be discrimination. There is a lot to think about: what that person wants, what those near to them want, what they have to bear as an individual belonging to a certain group, and so on. The answers change dramatically depending on the individual and the state of the world on any given day. Avoiding discrimination requires more than just choosing between extremes; it demands the strength to engage with the vast spectrum in between.

When you lower the resolution of an issue, commonalities become easier to see—but that is not the right approach. When you raise the resolution, you begin to notice the differences that were previously overlooked. That takes time. Simply reading someone’s tweet won’t increase your level of understanding. Ideally, everyone should develop their own ability to think critically, but as you pointed out, in the current climate, we cannot ignore the risk of reinforcing certain biases. That said, suppressing his voice entirely would also be misguided. Ultimately, it’s an issue of education. When I consider the situation, I genuinely don’t have a clear answer for what I should do. It changes every day. And perhaps that’s precisely why it needs to be staged as a play.

-

Set model for the original version by Kie Yamamoto, set and costume designer for Dodo’s Free Fall Photo: Akihito Abe

Lines should not be Overly Controlled

- Some scenes in the play might be perceived as discriminatory, depending on the audience. Were there any particular aspects you were mindful of while writing the script?

- Even if I have a specific intention as a playwright, as soon as an actor delivers a line, it can take on a completely different meaning. The audience may also interpret the work in ways that I never intended as the creator. While it is important to minimize misunderstandings, it’s equally necessary to allow for multiple readings. It presents an opportunity for both me and the audience to think deeply about things. If I focus on preventing misunderstandings, I can exert more control over the work, but in doing so, the level of nuance becomes tailored to each individual viewer. But granularity and the ability to put things into words are two different things. So when I write I am aware that I cannot one hundred percent control how it is perceived, and I try as much as possible not to write lines strictly based on intention.

When I write lines with the intention of steering a scene in a specific direction, I can’t help but feel like I’m manipulating my characters from above, like a god. Of course, I understand that I am the one writing it. The more experience I gain, the more technical skills I acquire. However, if I start adjusting dialogue solely to control the audience’s reaction—thinking, ‘If I write it this way, they will feel this way’—then it starts to feel like I’m writing an essay rather than a story. The most interesting moments come when I’m driven by a raw impulse to tell a story, rather than a calculated effort to shape each line.

- Does this way you don’t write lines with intention relate to how you direct the actors to perform?

- It doesn’t just apply to this work, but in particular with my works from the past few years, I have been striving not to impose fixed judgments on how things appear on stage—whether they are good or bad. I’ve been creating scenes where I would call the acting style naturalistic rather than realistic. That is what makes it possible to get multiple readings on something. The things happening onstage may appear to be good or bad depending on the viewer’s sense of ethics. Actors like Tetsu Hirahara and Ryutaro Akimoto who often appear in my works are really good at portraying characters with a naturalistic subtlety. I’m not the type who prefers the actors’ faces to be more prominent than the work itself, and I prefer the actors to have a sort of anonymity within the overall piece rather than performing in distinctive, easy to understand ways. In that sense, Hirahara and Akimoto are really good actors. Of course, I can’t say whether that’s good in other settings, but for me, I think actors who can perform while retaining an atmosphere of anonymity on stage are really fantastic.

-

Ryutaro Akimoto as Shinya (left) and Tetsu Hirahara as Natsume (from restaged version) Photo: Shin Sakomura

Major Changes in Restaging

- For the January 2025 restaging of Dodo’s Free Fall, you rewrote a lot of the script. Why did you rewrite so much of it?

- There were several reasons I rewrote it. I cut out the parts where I figured the audience interpretation would have changed a lot compared to when it was first staged. For example, the scene with Blue Demon we discussed earlier. At first, I wanted that scene to show the vibe of the characters but when I look at it now, I feel like the strong sense of discomfort overpowers the scene so I cut it.

But the biggest change was that, after staging the play once, I was able to get some distance from my own experience. As I was writing it, I often thought that if this had been someone else’s story, I might not have been able to write it at all. The inspiration for the work was something that happened to a comedian friend of mine, but at the same time, it was also about my own experience of watching over a friend who repeatedly said he wanted to die. That’s why I thought I could take on the responsibility of writing it. After the initial production, and now as it is being restaged, I feel that I am able to approach the writing with a bit more composure.

The biggest difference between the original version and the restaged version is the question of whose perspective the story is being told from. In the original version, the story progressed with the two perspectives of Natsume and his friend Shinya. In the restaging, it is written from just Natsume’s perspective. I think this makes the changes in how the people around Natsume see him and treat him much clearer, and above all I wanted to go deeper into how he feels about what is happening. In the new production, the name of the illness, schizophrenia, doesn’t come up but the story begins with the knowledge that Natsume is ill, so I think the way the audience receives it will be very different compared to the original performance.

-

The 2022 premiere of Dodo’s Free Fall

Photo: Naobumi Okamoto -

The 2025 restaging of Dodo’s Free Fall

Photo: Shin Sakomura

- Finally, a last word for people who have seen this work, or for people about to see it.

- The play deals with a niche, underground industry within Japan, and I hope people overseas will get a sense that this sort of culture also exists. Still, the work depicts how social titles and affiliations change how people are seen, and that’s not limited to the comedy world as I think it happens in many different parts of society.

And for example, people who actually need medical care but are not perceived as needing it, that may be an issue of transparency. I also hope it can be an opportunity for people to think about what someone like Natsume might want, and how to relate to such a person from outside that experience. One of the strengths of fiction is that it allows us to explore difficult questions without demanding clear-cut answers.

-

The 2025 restaging of Dodo’s Free Fall (2025) Photo: Shin Sakomura

Playwright/Director: Takuya Kato Starring: Tetsu Hirahara, Takenori Kaneko, Ryutaro Akimoto, Takafumi Imai, Katsuhiro Suzuki, Kyuichiro Nakayama, Yuni Akino, Mari Yasukawa, Kousaku Isahaya

Performance Dates and Venues

Kanagawa: January 10 to 19, 2025, KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre (Large Studio)

Osaka: January 25, 26, 2025, Kintetsu Art Theater

Mie: February 8, 9, 2025, Mie Prefecture Fine Arts Center Small Hall

Ibaraki: February 15, 16, 2025, Mito Arts Foundation ACM Theater

Special thanks to Takumi Theater Company