Workshops employing images derived directly from physical sensations

- There is a unique atmosphere to the performances in the Kochuten studio, with its 50-person seating capacity and its location in a building basement. This has helped win the series an especially ardent following, I believe. When I went to see a performance, there was a somewhat rowdy group up in the front and I realized later they were performers from Cirque de Soleil. I hear that you have done workshops for them. What do you teach in them?

-

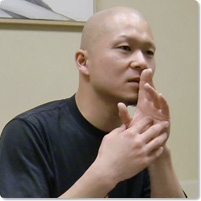

They are Corteo performers (laughs). I happened to be friends with one of the clowns performing in Dralion and through that connection I started doing workshops with them in 2008. They are top-class performers and when they first discovered the unique physical movement of butoh, they seemed to become very interested in it. For example, when someone is asked to an animal-like movement, they naturally tend to do poses or movements that look like some particular animal’s. However, in our butoh, we don’t approach it from visual forms like that. We take images based on the physical make-up and motion of a 4-legged animal and use them to become an animal.

This is just an example, but if the assignment is “movement of an animal that walks on four legs,” we get down on all fours and begin by creating a gentle wave motion along the back by using the image of taking in a small ball through the anus and working it through the body until it comes out at the top of the head. Then, to begin forward motion we don’t simply carry the body forward by moving the arms and legs forward but, rather, we use the power of that wave motion of the back to create forward motion. Once you master that motion, then we use the image of taking a ball from the right buttock and move it forward and out through the left shoulder and then do the reverse from the left buttock to the right shoulder, so we can get a walk that uses waves crossing the back diagonally in lines through the opposed buttocks and shoulders.

But this is still in the realm of an exercise. Once you can do this, we move on to inputting full-fledged images into the body to create expressive movement. For example, we say, “Imagine you are an animal in the jungle, on the ground and your body is such-and-such a size and you have hoofs and you are covered with hair and you have a tail and tusks and you are hiding in the dark as you walk.” This can produce unexpected movement that is much more interesting than simply recreating certain preconceived [visual] forms or poses. When this happens, you have left the realm of exercise and entered the realm of dance.

My teacher, Akaji Maro says, “Originally dance is “mime” in the sense of a child imitating an animal.” That is why we practice in this way until we can imitate animals properly. In my workshops, or when choreographing a work as well, we often use these types of images to imitate.

When I perform abroad I am often asked to do workshops, and when I do, I usually begin with the Maro Method (Rakuda (camel) exercises), which are based on the Noguchi Exercises (*1) to get the participants to experience the principle that the body becomes looser and moves more efficiently if you relax and don’t resist the force of gravity. After that we begin to introduce the Dairakudakan butoh movements. The Noguchi Exercises really appear to be quite interesting for foreigners, and I have been asked for a book on it that they could translate for their use. - Could you explain to us about the Dairakudakan butoh movements you just mentioned?

-

Akaji Maro defines three basic pillars of Dairakudakan butoh movement as “Choosing daily behavior Body Language” (Miburi no saishu), “Mold Body” (Chutai) and “Space Body” (Chutai).

“Collecting Body Language” is based on the idea that there is a sub-language of unnamed physical movements (miburi) that underlie the “actions” of our daily lives and that these movements can bring out dance.

“Mold Body” can be thought of as “forms.” It is based on the idea that, for example, when you accidentally spill some water your body freezes momentarily and that the “forms” that the body takes during dance come from those kinds of “forms the body takes when it freezes” (form as if cast in a mold), which occur as gestures in daily life. The elements that determine those forms are numerous and range from the person’s environment to disease and occupation. There is the bent-over posture of the farmer at work in his field and there is the bent posture of the aged and the feet-dragging walk of a person who is ill. The “Mold Body” concept of dance is one that involves dancing these mold forms excerpted from the physical forms and movements of daily life. But these “molds” are not restricted to things that have physical form. Feelings like joy and sadness also have forms. In order to create molds from such “forms” of emotions, you have to be able to sustain the specific “tension” of those emotions, so in our training we practice “carrying” those emotions without allowing them to break.

“Space Body” is based on thinking of things that are normally considered to be real as, in fact, empty and thinking of empty spaces as true reality. We have the common expression “It’s all thanks to you” (okagesama). The Space Body concept is one of applying that attitude to dance. In other words, it is the concept that we are able to dance due to the graces of the other. Take, for example, the act of “raising your right hand.” Under the Space Body concept you do not use your own will and strength to raise your arm. Rather, you take the approach that you are “being moved” by other forces. It may be the feeling that there is a string attached to your right hand that is pulling it up, or that the air under the hand is expanding and lifting it up, or that it is not air but water, or some sort of jelly, under your hand that is lifting it up. And, is it warm or is it cold, and does it hurt or does it feel good? It is the concept dance is born from the process of being moved as the result of a variety of things that you are feeling. It is not dance that is dictated primarily by your trained body but, rather, that “you” are in fact an empty space in the form of a body that is opened in some spot in the world and is being moved by the external changes in its surroundings. That is the Space Body concept.

However, it is not enough simply to have this concept in your head. You won’t be able to dance this way simply on the understanding you think you have of this concept. You have to train your body to be moved with your mind empty. You have to train yourself to stop the flow of thoughts in your mind. That is why at Dairakudakan we don’t have any such thing as a “Method for expressing sadness.” Instead we practice intensifying the emotion of sadness itself. That is the source of it all. There is no meaning in simply following a set of [dance] forms or poses alone.

Encounter with Butoh and Akaji Maro’s Presence

- How did you begin butoh in the first place?

-

My father was a scholar of English and American literature and my mother loved theater, so I was often taken to see Shakespeare or the plays of companies like Yumo no Yumin-sha as a child and theater was interesting for me. Around the time I was in my third year of middle school I was going to the theater by myself.

In high school I saw a broadcast on [the national television station] NHK-BS channel of Dairakudakan’s Ugetsu – Joten suru Jigoku. The opening scene where a line of men and women come on stage to a heavy clanking and clonking sound really struck me as hell (jigoku) itself, and I remember thinking what an amazing world they were able to create without even using words. Around the same time, a younger colleague of my high school art teacher happened to come to do trial lesson as part of his teaching training, and that gave me the opportunity to see videos of a number of butoh performances and things like Shuji Terayama’s plays. That made me take interest rapidly in the potential of the human body as a medium of expression and started me going to see performances by Kazuo Ono and Dairakudakan. I found that watching the physical movement of the butoh dancers was far more interesting than watching actors perform. The first time I saw Akaji Maro performing live was in a production of Waiting for Godot directed by Shoji Kokami, and his presence on stage was overwhelmingly powerful.

When I saw an all-male performance by Dairakudakan in the confined space of a small theater called Tiny Alice, I thought, “Here it is! Why am I not out there on the floor performing like this?” So, by my second or third year of high school I was determined that I wanted to join Dairakudakan. The high school I was going to was a prep school for students aiming to get into top universities, and when I told my teacher that I wanted to join this dance company named Dairakudakan, he was naturally quite perturbed. You can imagine how shocked he was when I told him that it was a company where the dancers whitewashed their bodies and danced that way (laughs).

It was decided that it would be best for me to go to college as well, and since I also had as much interest in poetry as I did in physical expression of the human body, I entered the literature course of Nihon University where Prof. Fumiaki Nakamura taught. I began going to Dairakudakan regularly when I was in my sophomore year of university (1997) and in my junior year (1998) I became an official member and began performing in their productions. - You had no experience in dance previous to that, so how did you learn butoh?

-

The first production I performed in was the Taiwan tour of Shisha no Sho (The Book of the Dead), and since it was a re-staging of the work, I first had some senior dancers teach me the part I was to do and then Maro-san checked my progress. My role was to keep walking with a carrying sack on my back, but it wasn’t going well. They had me practice walking like that for about four hours straight. At that time Maro-san told me a number of things, like, “Try walking like you are the shadow of a tired worker laboring under the sun.” Still it didn’t go well and I remember just practicing walking and walking and every once in a while one of the senior dancers would come over and give me a demonstration of walking. That made me happy but it was still a struggle to learn.

On the [Taiwan] tour we slept seven or eight people on the floor of a large room and I wasn’t used to that kind of group living. So for a while I said I would sleep inside the room’s bedding closet. But I didn’t want to be left out of the conversation, so I kept the sliding door of the closet open just enough to stick my head out (laughs).

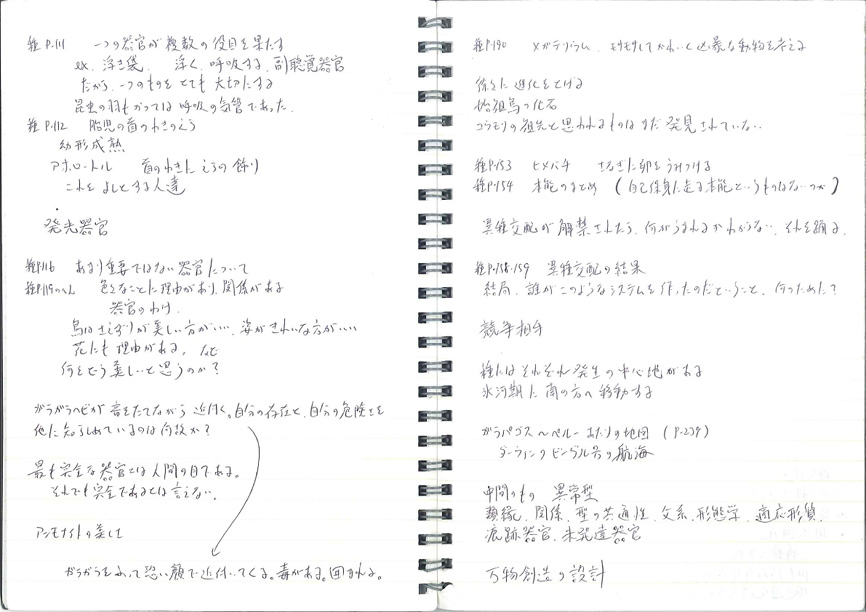

Every summer, Dairakudakan has a retreat at Mt. Hakuba that is attended by about 35 people, about half of whom are foreigners from about ten countries around the world. At this nine-day, eight-night retreat we practice from morning till night. The thinks Maro-san talks about at those retreats are always so interesting that I keep “Maro-san Lecture Notes” for my own personal reference, and I find so much that I want to write down that I end up one notebook one time. The first day he hardly talks about dance at all. One time it might begin with talk about ancient ritual sacrifices. Another time it might begin with talk about the origins of the word mai (dance), and then he will take these examples and connect it to the Dairakudakan methodology, saying, (And that is why I believe dance is such-and-such…” Maro-san is always approaching things from new places and continues to change, which I think is amazing.

Anyway, we all spend a long time together, cooking, eating, practicing. Just when you think someone is talking about serious dance criticism, you find them talking the next moment about what you should do to improve the taste of the food you have prepared (laughs). The time spent in those retreats is very full in quality and meaning.

But it is by no means a family type of environment. The family is the place where you can let down your guard and maybe ask favors or be childish at times, but Dairakudakan is the exact opposite. You can’t show that you are tired, and even if you have strained your back you still have to go on stage when the time comes. But, despite that tension and responsibility, it is still a place where you can maintain very good interpersonal relations. I believe that is because of the important prerequisite that, despite the fact that everyone is different and everyone is leading a life of their own, they have all gathered here under Maro-san to dance seriously with a shared consciousness.

For me the first stages of Dairakudakan I saw were my first really moving experiences art and I knew that this was something that I could continue for life without wavering. For me, Maro-san’s presence is like a solid and unmovable mountain at the center of my life.

The world of Ikko Tamura

- This year marks the 10th year since the Kochuten performances began, and until now 18 butoh artists have presented a total of 38 works in the Kochuten series. In recent year the performances have been mounted at a pace of about one every two months and some have runs of longer than a week that attract a young audience. You yourself have presented three works in the series, including Zattoh Libertine, which won the New Artist Award of the Japan Dance Critics Association Awards, Chi (Blood) (2008), which was invited overseas, and Omamagoto (Playing House).

-

Soon after I joined Dairakudakan, the younger members of the company began presenting their own works in what was initially called the “Jarezoku” series, and then the Kochuten Performances series began as a full-scale program in 2001. The styles of butoh differ with the artists and some take an attitude that it is enough simply to have a body, but I like to spend time going around to used-book shops gathering material and then choreographing pieces in careful detail. Sometimes I’m told not to pretend to be too intellectual and get big-headed about it, but I really love the time spent buried in the materials I have gathered and thinking this-and-that to work up a piece.

Blood, which I’m performing again this March in Fukuoka, is a piece where I wanted to attempt to trace my roots back, so I got a number of books on things beginning with Darwin’s theory of evolution and coming up through modern genetics science. Reading these books and looking at a thick book of photographs from the Galapagos islands, I thought about how to compose the piece. As a result, in the final staging had something like a family tree of life forms (laughs).

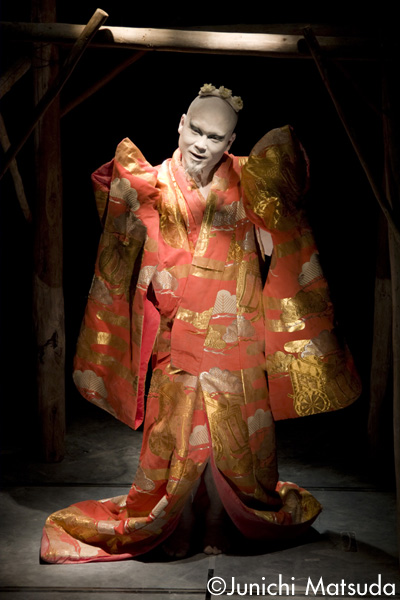

Naturally, when I create a work I have to think not only about the choreography, directing and performing but also about all the details of the stage art, costume and music. In short, balancing the pluses and minuses of all the elements is important the tough part of creating a work, and finding the right balance and flavor is the toughest part as well as the most enjoyable part of the creative process. When I think about costumes, for example, the most powerful costume for Dairakudakan is whitewash on the bare body, so putting any costume on that body runs the danger of adding unnecessary explicitness. But it is also too easy to just say, “OK. Everybody will perform without costumes.” So, I am always thinking about what is necessary for the piece and for each dance and what can be eliminated. It has been a process of trial and error for me. For my last two works the music has been created for me by the shakuhachi flute artist Keisuke Doi, who works with the famous Japanese drum artist Eitetsu Hayashi and the pianist Kensaku Tanikawa. He has said he will do all the music for my works, and so I have gladly accepted. The pieces he composes on the computer truly have soul in each and every sound. I tell him the image I have in mind for a piece I am choreographing and he is able to compose music that expresses the essence of that world I envision with amazing faithfulness. I am confident that we will be able to work together from now on to explore new worlds that only the two of us working together could create.

I also write poetry and I sometimes use poetry to communicate to the dancers the core images of my works. I believe that the creative process for a butoh work is fundamentally different in Butoh is different other forms of dance where a choreographer composes a piece and the dancers perform it as it is written. In my case, I create what we call a “choreography notebook” (furicho) consisting of words and illustrations to record the composition and ideas behind my choreography. For a scene where the movement involves only standing, swaying and then squatting my notes still fill up about three pages. It is not simply a record of the movements. I record what is going on inside me when I am standing and swaying and how it felt. In essence it is a record in words to provide clues for re-creating the feelings involved, not the movements themselves. All of us use this type of notebook when composing a butoh work.

In my case, I always keep a notebook with me to record things that I find of interest in my daily life. For example, when I learned that an egg goes through a weakened period on the fourth day, I write that down (laughs). Anything is worth writing down for me. Even if it is not immediately of use, later when I am composing a piece “Inside the Egg” I will look back at my notes and realize the reason that the piece wasn’t quite right at a certain point was because it didn’t include that weakened point. Also when I might be composing a scene that involves the growing of a fetus and I feel that it goes too smoothly, I can remember those words and make a change so that the fetus goes through a weakening stage at one point.

Notes that a butoh artist makes to record his own body movements will be different in some ways from the notes a choreographer makes for directing dancers to perform a dance piece, and I think that, as long as each uses words that have reality and meaning with regard to the respective bodies, there is nothing wrong with them being different. But when Western dancers see this [kind of notes] they are surprised and ask if it is really possible to do dance work from them (laughs).

However, due to the time that Dairakudakan butoh artists spend practicing together and living together at retreats and such, we share a common vocabulary of physical movement. For example, if we say something seemingly unspecific like “gunyan de yotsu” (four crooked twists), it communicates a clear image for us. Then we move on to the process of talking about “ma” (spaces, pauses, intervals). Movements become defined by the ma they involve. For example, if you are slapped in the face you will turn in one second and say “What was that for!” But there could also be a feeling that takes you four second to turn back from the slap and then say “What?” But it is never enough to just count out that ma (interval) one, two, three …. What we want is to find the emotion that occurs when you are slapped. It is not the interval count but what is nurtured in that time, what is hidden beneath it, what is moving. And, with regard to that, I believe the members of Dairakudakan have a lot of shared consciousness. So, the first thing new members need to do is to be able to grasp that sense.

When I create a new piece, even if the overall composition and the choreography for the other dancers are going well, I always struggle with my own solo parts. Maro-san tells me that he thinks it is OK if I choreograph [the solo parts] for myself just like I choreograph the parts for the other dancers, but it just doesn’t seem to go well. No matter what the case, it is always difficult to treat oneself like you treat others.

I usually first show Maro-san my new works in a full rehearsal about a week to ten days before the premiere, and that is always a very tense moment for me. All the Dairakudakan members who have presented works in the Kochuten series say the same thing. We all think as we are walking the road to the Kochuten studio, “If only that truck would hit me, I wouldn’t have to go to the studio (laughs). That is how intense the mental state becomes. But, nonetheless, we still want to create works. It is a matter of cause and effect.

The encounter with Joseph Nadj

- You and three other Kochuten members performed in the Japan-France collaborative work ASOBU choreographed and directed by Joseph Nadj that opened the program of the 2006 Avignon Festival. Also, in 2008 you spent three months studying at Nadj’s company in France on a Ministry of Culture’s foreign study program for the advancement of emerging artists. How did you first meet him?

-

For ASOBU, I was chosen by Nadj when I joined one of his workshops on a whim, not knowing that it was also in effect an audition for the dancers to perform the work. It premiered at Avignon and then we toured with the production for quite a number of performances.

Nadj never told me to do butoh. With ASOBU he based the work on Henri Michaux and gave us crazy subjects like “an elephant melds into a mosquito” and then say, OK, go ahead and try doing it. I said to another dancer, OK, I’ll be the [elephant’s] ear and you do the nose and we’ll melt with a gunya movement and become mosquitoes, and then we just did it. Rather than thinking about the subject, we just let the words translate directly into body motion. It seems that Nadj loves that kind of thing, so we communicated well from the beginning.

If we had tried to give expression to our Japanese-ness or butoh, I probably wouldn’t have worked. Our bodies are steeped in so much of Japanese culture and habits that it naturally comes out without our even being conscious of it or trying to express it. So, I believe, if we simply pursue our realities, it naturally comes out as originality. What Nadj wanted, I believe, was not something butoh-like but something Ikko Tamura-like.

In Europe, it appears that Nadj himself is considered butoh-like and I thought a lot about why that is. Because I felt that way too. So I thought that studying Nadj’s butoh-likeness would be a process of re-examining my own butoh. One of the big factors, I found, was the place where Nadj grew up. I was born and raised in Tokyo, so I don’t have unique origins and original (primal) memories like Maro-san has being born and raised in the ancient capital of Nara or [Tatsumi] Hijikata had being raised in rural Akita in the north. Now I am at the point where I can say that Tokyo has provided my origins and original (primal) memories, but for a while in the past I had a strange sort of complex about it and worried whether someone born and raised in Tokyo could ever become a butoh artist. That is part of the reason why I very much wanted to see Nadj’s hometown. So, I made the request and was fortunate to be taken there to see it.

Nadj’s hometown is near the border between Hungary and Serbia and it is a beautiful town called Canilla, but it also happens to have one of the highest suicide rates in the world. What’s more, they seem to compete in choosing the most terrible ways to kill themselves—like running into a sharpened stake so it pierces the throat.

When I watched Nadj’s works after having actually been to Canilla and feeling its atmosphere, breathing in its air, smelling its earth and the meeting its people, I sense that place very strongly in his works. There is a solo piece, for example, that was created as an homage to a friend of Nadj’s from Canillia who as a poet that committed suicide. There is a drizzling rain and Nadj is there in a corner dancing continuously. You get the sense that there was nothing in that place to play with so he just played by himself that way. That poet hung himself from a doorknob, and that is a motion that Nadj repeats again and again in one scene. In that work Nadj experiences the same despair and the decision to die as his friend did, but instead of dying he chooses life. It is a work that makes me feel Nadj’s strength within sadness, as he rises above the anger and pain of his friend’s death and attempt to cleanse it in that way. I felt that the way he dealt with human life and the posture that shows a life-long relationship with one’s origins truly had a lot in common with butoh.

When I went to France to study at Nadj’s company for three month, everyone was surprised when I introduced myself as someone who had come to study butoh from Nadj. Over there, people thought that we learn butoh from childhood just like they learn ballet from childhood in Europe. So, they couldn’t understand what I meant by learning butoh from Nadj it seems (laughs). But, it’s like asking what is butoh in the first place. Nadj uses completely different modes of expression in different works he doesn’t concern himself with traditional boundaries between the disciplines, like “This is dance” and “This is sculpture.” In the same way, I am not trying to do “Butoh.” I am content to leave the definitions of what I am doing to the viewer. Rather than re-doing my past works in new variations, I believe that true originality means continuing to pursue your realities of the moment. And, I believe that the door to yourself that I am constantly trying to open can become a universal door for others. I felt that kind of similarity with Nadj. He is definitely someone who has been an influence in my life.

Things butoh-like

- Dairakudakan and Kochuten have firmly inherited the butoh style of whitewashed naked bodies that has existed from the early days of the butoh as an art form. At the same time, however, you have not inherited the legacy of the early butoh artists in an easy fashion. Young butoh artists have continued to establish their own artistic worlds and, more than anything, you have continued to produce physical performance that fascinates the audience. This is an incredible thing. What is the secret of this success?

-

I believe that this body is steeped in many aspects of contemporary life. But, I feel that butoh is something more spiritual and universal. I absolutely do not believe that butoh is only possible if you return to [references to] your personal place of origin—which I talked about earlier—or that butoh ended when [Tatsumi] Hijikata died or that when non-Japanese do butoh it is not real butoh. I believe that butoh is the process of constantly thinking about what to dance with this physical body that has been inherited in an unbroken line since ancient times. And that is the butoh that I want to continue to pursue from now on.

That said, I have no intention of trying to use my work to broadcast a message “This is Butoh.” Also, not one of the directors who have become interested in me and asked me to perform has ever asked me to “do butoh.” Of course, the vocabulary of dance that I possess is in the butoh style and has a Dairakudakan flavor, so these aspects naturally come out when I perform. And I believe that is why [some directors] have been interested to see what will happen when they have Ikko Tamura perform a particular role in a particular place.

The minute you try to “do butoh” it stops being butoh, I believe. That is why I must constantly be thinking about how I should exist in each given time and place. And that is why in my work and my performances I always carry the awareness that my presence when standing on the stage has to be stronger than that of the others working up a sweat as they move around the stage.

Maro-san makes careful distinctions about when he uses the word butoh and when he avoids using it. Rather than saying that I want to carry on the butoh tradition, I would say my true feeling is that I want to continue to pursue what Akaji Maro has been pursuing as an artist. At the same time I am aware that anything I would do in an attempt to imitate Akaji Maro would never exceed the level of imitation. He continues to transcend anything that the young Kochuten artists try. My intention is not to try to steal the fundamentals of his thought and the source of his ideas but, rather to experience and enjoy his life in art. Watching Maro-san and working in close proximity is an ongoing repetition of surprise followed by convinced enlightenment. That’s surely why it is always fascinating and keeps you watching so you don’t miss a thing. In fact there have been so many times that I experience things that make me realize the meaning of words Maro-san said to us years before. That process of discovery has been repeated over the dozen years I have been with Dairakudakan. And that is what why I feel that it is just too fascinating to ever quit (laughs).

In the past there was a work created by one of the senior dancers of Dairakudakan and with one word from Maro-san it was decided just before the performance not to use whitewash. It was based on his decision that whitewash was superfluous with that particular work. There was one time when we were riding in a train and Maro-san asked me why I had shaved my eyebrows (laughs). “What? But everyone [in Dairakudakan] shaves their eyebrows,” I said. “You see I still have my eyebrows,” he replied. In other words, it is free, there are no rules (laughs). It is not a case of relying on a certain look, it is rather a matter of things that have been arrived at in the course of pursuing their art.

Originally, butoh was a movement in opposition to the values of the establishment at the time, and eventually other movements arose in opposition to butoh values. That process of revolution in the movements has been repeated a number of times since. That is why I make appoint of saying to young aspiring dancers that this is art that you put your entire body and soul into. I say, “If this isn’t art, what is?” Every era has its trends and fashions, but we are not concerned with those. I want to continue to do dance in a pursuit of primal and universal elements of human existence, such as making dance about the surprise and awe human beings felt when they first saw fire.