Masashi Nukata

Entwining the Culture of Theater with Music—The Dramaturgy of Nuthmique

Photo: Kikuko Usuyama

Photo: Kikuko Usuyama

Masashi Nukata

Born in 1992 in Tokyo, Masashi Nukata is a composer, director, and playwright. He majored in composition at Tokyo University of the Arts, with a focus on contemporary music, stage music, and film scores. While still a student, he founded the eight-member contemporary pop band Tokyo Shiokouji, where he plays keyboard and composes, blending minimalist music with diverse genres. His graduation production, Sorekaranomachi [The town after that], won the Grand Prix for the Aichi Arts Foundation Drama Award in 2015. In 2016, he established the theater company Nuthmique, consisting of performers from various disciplines—such as actors, dancers, and musicians—for which he writes and directs. As a musician and composer, he has also worked on stage music for plays such as Satoko Ichihara’s The Bacchae – Holstein Milk Cows, as well as numerous advertising campaigns.

While studying composition at university, Masashi Nukata formed Tokyo Shiokouji, a band that brought a contemporary pop twist to minimalist music. Alongside this, a musical fascination with language also led him to launch the theater company Nuthmique. Nukata analyzes the structures of both music and theater to create original stage works that focus on the relationships between sound and language.

Nukata aims to create new, unprecedented musical plays through his exploration of the nature of theater and the Japanese language. In this interview, we take a look at where this rising musician stands today.

Interview and text: Masahiko Yokobori

English Translation: Yume Morimoto, Ben Cagan (Art Translators Collective)

- I believe it’s right to say you wear three hats: composer, director, and playwright.

- For me, being a composer is my primary identity. I’ve always been fascinated by the fundamental, even primitive, elements of music—the arrangement of notes, how the sounds resonate—from my early days, and that’s never changed. It’s only in the last couple of years that I’ve started having the confidence to refer to myself as a playwright.

- You studied at Tokyo University of the Arts’ Faculty of Music.

- I spent so much of my time on activities off-campus during my student days that I don’t really have many memories of life at the university itself. WONK’s Ayatake Ezaki, the drummer Shun Ishiwaka, and King Gnu’s Daiki Tsuneta were all in my year, and we’d plan live events together outside school. And the composer Yuta Bandoh was in the year above us. Inspired by my interactions with all of these people around me, I formed an eight-member band called Tokyo Shiokouji in 2012, my second year at Tokyo University of the Arts.

- So, how did you come into the world of theater?

- As I remember it now, I saw a recording of chelfitsch’s Five Days in March during my freshman year. Up to that point, I’d only seen Shiki Theatre Company productions or school plays, so it felt so fresh when chelfitsch showed me that it’s okay for the actors to speak softly, or for incomprehensible things to happen. I’ve always liked contemporary and electronic music, and I realized that theater allows for that same complexity, for approaches that demand a certain literacy from the audience while also transcending what the audience may be familiar with.

- Do you recall what the first play you saw in a theater was?

- I don’t remember the first, but I went to see a Religious Theater Group Pyaaa!!1, because a classmate from my seminar group said they would be performing in it, and they really left an impression on me. My classmate was playing the role of “Shibuya” and spoke as if they were actually that area of Tokyo. That’s the kind of play it was, and it made me think about how that sort of thing probably couldn’t be achieved in film. It taught me that, in theater, people can play non-human roles, and embody more abstract concepts.

- Which directors and playwrights influenced you back then?

- When I was reading Oriza Hirata’s Engeki Nyumon [Introduction to theater], I thought it was great how much time theater dedicates to rehearsals. Back when I was creating music at Tokyo University of the Arts, I was really frustrated at only having two or three rehearsals with the performers, so we could never really put in the proper time. There was a disconnect between the creative process I was looking for, and how things were done in the industry. I thought that perhaps bringing the culture of theater into the mix might allow the creation of works with something new to them, and music and theater have come to function as the twin axes of my practice.

I was also struck by Hirata’s methodology—that is, his way of articulating things. Generally speaking, music textbooks make for difficult reading. I understand John Cage’s writings, the content of them, for example, but they’re incredibly complex, and people like Yuji Takahashi use a lot of poetic expressions [laughs]. There is also something engaging about that. Oriza, on the other hand, goes beyond the purely abstract side of art, and I think that also had an influence on me. In terms of other playwrights, I’m also a big fan of Shiro Maeda, and I often read his works.

-

University graduation production Sorekaranomachi [The town after that] (2015) © Mahaya Takara

- And then, two years after graduation, in May 2016, you founded Nuthmique.

- The name came from a pretty carefree kind of thinking: my mother ran a eurhythmics2 class, and I took the “nu” from “Nukata.” Initially, I started it with a friend, and there were just two of us. Then, in 2018, the producer we had at the time left, and actor Shiho Fukasawa and producer Haruka Kawano joined. Then, the actors Tsumugi Harada and Wataru Naganuma became part of the group in 2019 and 2020, and we’ve been a five-person team since then.

Being a musician at heart, I know from experience how valuable it is to have the same band being together consistently over time. My view is that working with the same people, you build up an incredible depth of skill together, and that ultimately feeds into improving the quality of the work. That’s why we hold regular monthly meetings even when we don’t have any performances coming up.

- What kinds of things do you talk about in those meetings?

- We just chat. We started the regular meetings in the first place because I’d consulted with art manager Yuko Uematsu about how I was struggling with running the theater company, and she advised me that we should just get together and chat. There was actually a performance in 2021 where all of the members shared the view that things hadn’t gone so well. Looking back on it now, I think that at the time I wanted to change how I was writing my scripts, and they just weren’t that compelling. The members of the company are always keenly aware of when our work isn’t very interesting, and although everyone did their best to try and make it work, communication among us was getting harder and harder.

Now, our meetings take on a more long-term perspective. I’m trying to share a broad vision of what kind of work might be interesting five years from now, or what things might be like if we kept going for 20 years, rather than talking about what’s right in front of us.

- How do you differentiate your work with Tokyo Shiokouji and Nuthmique?

- Each group has different members, and live performances and the works themselves take shape around those members. So, it feels like it’s less a case of me differentiating between the two, and more that the groups are naturally different. For example, I can’t even imagine creating theater with my Tokyo Shiokouji bandmates. That group formed before I became interested in theater myself, and none of the other members really care about that world. Most of them don’t even come to Nuthmique’s performances [laughs].

-

Tokyo Shiokouji live performance © Hayato Watanabe

- I’ve asked about your influences in the theatrical context, but what about your musical influences?

- I love how Yoshihide Otomo3 has been able to keep producing new work that brings his own personal style into so many different genres. Even more than that, he tackles larger projects but also performs in smaller live events for around ten people, working with a team and approach suitable for the times. To me, that’s the ideal. Actually being able to pull that off is no mean feat, but he’s been able to do it, and explore his own musical interests through it all. I have nothing but admiration for what he does, even his ventures into areas that hardly seem like music at all.

- Otomo also gives improvisational musical performances, I believe. Are you the type of person who creates works in advance of the rehearsal process, or is it more your style to create during the rehearsal stage?

- I’ll have the sheet music, and I’m not too slow with preparing a script either, so I think I’m the type to come to the process with a fairly set direction in mind. But, honestly speaking, it can be pretty painful to watch a performance where the musicians or actors are unable to use their own initiative to the musicians or actors. Speaking as a band guy myself, I feel like people in bands basically all want to do what they want, in their own way. Maybe that’s where theater companies and bands differ. Bands do have leaders, but they’re still a collection of individuals with their own strong opinions and styles, so there’s a certain equality to the dynamic that takes shape. I’d like to bring this brilliant cultural side of bands into the theater setting as well. Of course, it will take considerable time to get there. I think my desire to build this sense of collectiveness is connected to why I prefer ensuring plenty of time for rehearsals.

- So, you find the range of small and large-scale projects Otomo gets involved with ideal. I see that Nuthmique has also been engaging in smaller-scale projects.

- Yes, Nuthmique Yose [yose are theaters that specialize in popular entertainment like rakugo and other storytelling, music, and magic acts] was a small production we did in 2024—a one-person play performed in a traditional Japanese house that held about 20 people. In 2025, we also created Mittsu no Mitsu [Three Meets], which was a piece performed in a space that fit only about 30 people. Within my own practice, in 2014, I collaborated with James Harvey Estrada4 from the Philippines to present the work Pagkalinga : Vibrations and Rituals of Care. In this piece, we went around to various locations, including churches and old houses, where James would use his non-fluent Japanese and speak in Tagalog or English—we didn’t know if the audience would understand those languages. I felt firsthand how there are performances that can only be done in intimate spaces. Based on these experiences, I’ve recently been thinking about how what can be depicted in a work depends on the size of the performance space.

-

Pagkalinga : Vibrations and Rituals of Care (2024) © Mizuho Watanabe

-

The Religious Theater Group Pyaaa!!

The Religious Theater Group Pyaaa!! was founded by students at Tama Art University. Led by Tomoki Tsukada, Pyaaa!! was active until around 2014.

-

Eurhythmics

Eurhythmics refers to a musical education methodology developed by the Swiss composer Émile Jaques-Dalcroze (1865–1950). Rhythm, concentration, and creativity are cultivated through physical expression with music.

-

Yoshihide Otomo

Born in 1959, Yoshihide Otomo is a guitarist, turntables artist, film score composer, and producer. While his main projects are the Otomo Yoshihide Special Big Band and ONJQ (Otomo Yoshihide’s New Jazz Quintet), the musician also works with many other groups and turns his hand to projects across a range of genres.

-

James Harvey Estrada

Born in 1986, James Harvey Estrada is a director, performer, and video artist from the Philippines. His works include Hear, Here!, which empowers people with hearing disabilities.

https://tokyo-festival.jp/en/program/ostrich/?utm

- You also directed a production of The Glass Menagerie, outside of your activities with Nuthamique and Shiokouji, and released your lengthy direction notes on your personal blog.

- I have two aspirations—one of which is to change Japanese society’s image of a theater director. I recently saw a television program that portrayed a director getting very angry during a rehearsal, which I really hate to see. I don’t mean to disapprove of anyone else’s directing methods, but I believe that choosing anger as a means of communication exposes a lack of skill on the director’s part. That’s why I want to show that the role of director is one that does require skill, and I believe it’s important to embody that. That’s why I decided to leave behind that kind of written record.

My second ambition is to try to create a new style of musical plays that makes use of the Japanese language. In Japanese theater and music, there tends to be an unconscious admiration for things outside of Japan. For me, however, I’m currently very interested in exploring how Japanese itself can be treated within musical plays. I don’t mean this in a nationalistic sense, but I believe that inquiring into our own language ultimately leads to creating a more global work.

More specifically, I want to use the power of music to expand the range of sounds that Japanese has. For example, when music plays in a room, people naturally raise their voices. Or, a term like “aishiteru [I love you]” is not something we usually say in daily life, but it’s interesting how we can sing it when it appears in lyrics at a karaoke, for example. What I mean is that, when music is involved, it somehow influences the way that we speak in one way or another. I have a sense that the addition of music expands the range and realms that Japanese can access within me, and I want to contemplate that sensation through my mother tongue. By doing so, I hope to create musical plays that are rooted in our contemporary linguistic perceptions.

-

The Glass Menagerie (2025) © Yasuhiro Nishi

- I also feel that compared to international theater, the way Japanese theater uses music can be rather uninteresting. When you watch theater works, I’m sure there are moments when you think you might have done something differently.

- In general, I have respect for all kinds of work. That said, there are moments when I feel a piece could have gone a bit further. For example, the use of a style that sits between rap and acting in mamagoto’s Our Planet was really impressive, but the pitch was off in the last scene. I remember thinking it lost a sense of cohesiveness in terms of the musical quality. Given that the piece incorporated repetition and rhythm in the dialogue, I thought the idea could have been refined a bit more. I also feel that Japanese theater, in general, isn’t very interested in the finer musical details.

- I’d like to expand on this conversation a bit further. Could you share more about your thoughts on the use of music within theatrical works?

- When creating stage music, the text is the priority. For example, I composed several songs for Satoko Ichihara’s The Bacchae – Holstein Milk Cows, but rather than thinking about my style or other things, first and foremost the music had to properly deliver Ichihara’s text. I believe that the music should be there to tighten the relationship between the text and the audience. There are certain limits I have within myself in terms of style, but I constantly prioritize creating the type of sound that is demanded by the text.

Actually, the way in which stage music is created is very limited. My recent thinking is that there are really only four approaches. The first is a type of background music played to signify the passage of time, much like the effect of a blackout or a change to the background color. The second goes a bit more into text itself. For example, there might be sound effects that go off when someone speaks, or the volume suddenly rises. Here, the sounds are bound by a relationship with the text. The third is when there is a musician on stage, and they are playing music. When the musician is treated as one of the performers, the music exists on the same plane as the performers, in a position of equality. The last is having music intentionally unaligned with any of the aforementioned elements.

You mentioned earlier how music in Japanese theater is uninteresting—I would personally add that within Japanese theater, many works only use sound in one of those four ways. If they choose to treat it as background music and never stray from that approach, I think it’s difficult to make an interesting piece. Personally, I find Junnosuke Tada’s works stand out in this regard, and I really enjoy his way of using music. Not only are existing songs used with a particularly compelling taste, but they also achieve multiple theatrical effects. While functioning as background music, the music genuinely influences the actors, and the way it meshes with the text is truly remarkable.

- You mentioned at the start of the interview that it’s within the last two years that you’ve gained confidence as a playwright. Is there anything you want to write in particular moving forward?

- Recently, I’ve realized I’m very interested in words, especially in styles of writing. In terms of content, I believe theater can achieve something that differs from the way we share perceptions on social media timelines, where we’re constantly conscious of how we’re being perceived. Theater can bring to the stage the things we want to say in daily life but can’t, or the kind of frictions that could never occur in reality. As for writers, I think I’m influenced by William Faulkner. I also enjoy Jon Fosse, so I’d like to do something with that.

More specifically, I would like to show audiences a timeline that shouldn’t have existed, like something out of a multiverse—where events that shouldn’t happen occur, and then it becomes unclear whether they actually ever took place or not. For the past few years, I’ve been drawn to questions like whether a single suicide stems from personal issues or from broader societal factors. This theme also appeared in my previous work, Itsumademo Hateshinaku Tsuzuku Boken [The endless adventure that goes on forever] (January 2025), and continues in my newest work, Kanata No Shimatachi no Hanashi [Tales of islands beyond] (November 2025). In my playwriting, I’m exploring how to blur the boundaries surrounding death.

-

Itsumademo Hateshinaku Tsuzuku Boken [The endless adventure that goes on forever] (2025) © Mahaya Takara

- Thank you for your time today. I feel that creating a new style of Japanese musical plays will likely become the focus of your future activities.

- Yes, I would say that’s right. That’s what we’re aiming for with Kanata No Shimatachi no Hanashi [Tales of islands beyond], and I think that’s essentially what we’ll be pursuing over the next few years. Actually, I recently came up with a new idea—at the 2025 Toyooka Theater Festival, we did a reading performance using a new English translation of Naoya Shiga’s At Kinosaki. Through that experience, I really felt that the musical approach I’m developing could also be applied to other languages. Building on that idea, I’d eventually like to create multilingual musical plays—although that may be something for the more distant future.

-

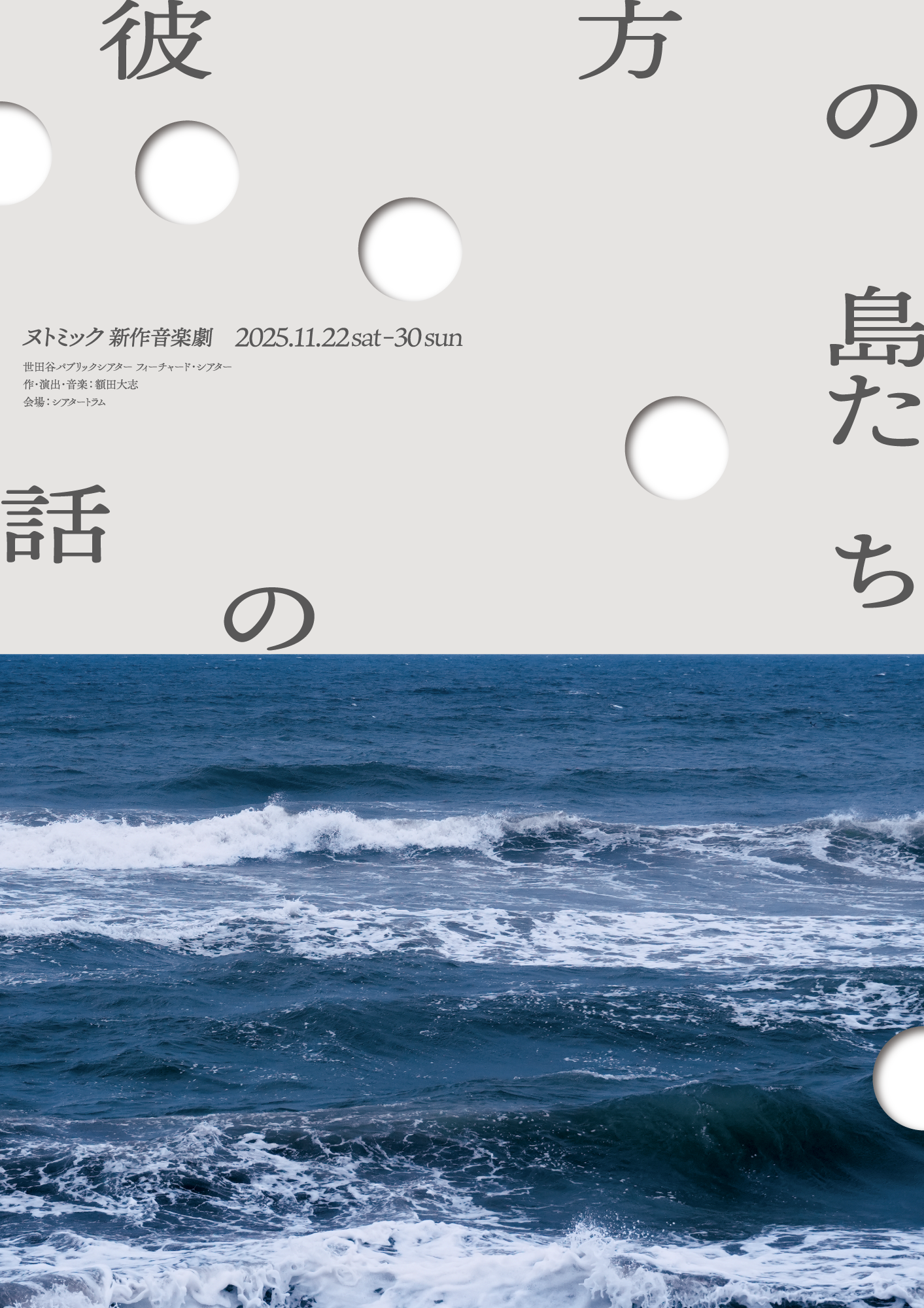

Kanata No Shimatachi no Hanashi [Tales of islands beyond]

November 22–30, 2025, Theatre Tram

Written, directed, and composed by: Masashi Nukuta

Cast: Miho Inatsugu, Hairi Katagiri, Seiji Kanazawa, Ryohei Higashino, Wataru Naganuma, Tsumugi Harada

Guitar: Tokutaro Hosoi Bass: Haluna Ishigaki Drums: kent watari

Inquiries: Nuthmique

-

Photo: Kikuko Usuyama