- Would you please begin by telling us something about the main activities conducted by the Attakkalari Centre for Movement Arts (hereinafter Attakkalari Centre)?

- The main activities are research and education regarding traditional dance and contemporary dance as well as creation of works. I first studied traditional Indian dance and then went to the U.K., where I studied contemporary dance, and I was active for 14 years as a dancer and choreographer. After returning to India, we opened the Attakkalari Centre in July 1992.

- What was your reason for choosing Bangalore as the location?

- In my native Kerala it was so difficult to get any money, and in Chennai where traditional dance is popular, it is rather conservative, and in Delhi the political atmosphere is too strong, and Mumbai (the center of Bollywood (*1) is too commercially oriented. In contrast, Bangalore has a good mix of traditional and new culture, and the climate is also good, so you can work year-round. That is why I chose it.

We renovated an old garage, but there were so many rooms in between. So, we demolished all of that, made a big hall, and there was office upstairs. Then we extended that to have two studios. In India, dance is usually done on concrete or stone floors, so that caused a lot of knee trouble. So, I had a friend in Britain send me a sample of a dance floor that was made of layers of wood with cushioning material in between, and then I had the floor material made at a plywood factory. Another friend from Britain also contributed linoleum mats for us. That is how Attakkalari Centre was able to open as the first facility in India with a specialized dance floor. - What is the meaning of the “Attakkalari” in the Center’s name?

- In Dravidian terminology which is prevalent maybe in the root languages called the South Indian languages, Attam means performance, and Kalari means an arena, so Attakkalari means a performance space. At first, we called it the Attakkalari Centre for Contemporary Performing Arts.

- How did you get together the funding to open it?

- At first, I was investing whatever little money I had earned working in London to start the process. Then, when we sought funding for a dance education program, the Sri Ratan Tata Trust gave is some funding for the project. This education program was well received, and that led us to set up a not-for-profit public charitable trust. And there was a lady who was working at the Tata Trust who believed in us and helped us set up the charitable trust.

The starting capital for the trust was about Rs 12 million (approx. 18 mil. Yen), and then five years later another Rs 4 mil. (approx. 60 mil. Yen) was added and later another Rs 4 mil. was added. The idea was that we could use 50% of the interest earned from that money for our administrative work at the Attakkalari Centre and the other 50% would be added to the corpus fund.

Currently, we receive funding from the Sir Ratan Tata Trust, the Department of Culture Government of India, Fanuc India Pvt Ltd. and TNQ Technologies Pvt Ltd. By the way, Fanuc India Pvt Ltd. is a company that makes industrial robots, but the parent company is a Japanese company. TNQ Technologies is a Chennai company that edits a magazine of the medical industry. - When the Centre was founded in 1992, what was the dance scene in India like? We have an image of Indian dance as being strongly oriented toward traditional dance.

- Yes, I should explain a bit about what the situation was like on the Indian dance scene in 1992. When we started the Attakkalari Centre in the 1990s, there was no virtually contemporary dance. But there exchanges between Indian and European dances. You know the musician, Ravi Shankar, his brother Uday Shankar? They worked with Anna Pavlova (1923). Uday himself was not a trained dancer, but he had set up a center for Indian culture in Almora in northern India and it ran for around four years. And that was a very good concept for that time. He brought many, many teachers, very eminent teachers of different Indian physical traditions.

And there was a project, I heard in the 1970s, to set up a contemporary dance institute. It just got completely bogged down in the bureaucracy. We have institutes for contemporary visual arts. We have institutes for contemporary theater. There was no institute for dance because of this kind of issue. Because it’s also connected with the religion. So, there was difficulty. In music also there are a lot of experimentation. So, dance had a bit of problem. - May we ask where you were born?

- I was born in Kerala in Thrissur district. My both parents were teachers. My father was headmaster and my mother was also a teacher, so there was no connection to dance there. Dance was not very much encouraged, especially for boys, even though the community I come from there are traditionally dancers and martial artists. But most of the Kathakali artists are men and many famous dancers come from that community. When I was a child, I did learn some traditional dance and the traditional martial art called Kalaripayattu.

- In India, do all children learn traditional dance?

- No, not everyone. So, because when we were young, that is the time the families became molecular family. Until then it used to be a big joint family and woman is more powerful. It’s a matriarchal system. So, the property goes to the woman. We grew up with a lot of children together. So we would roam around, and it was very fantastic childhood. But when I am studying, I was very good at studies and I was first in school and all. So, I got four scholarships to study for my higher education in college.

- At college you majored in physics, didn’t you?

- Yes, but from the age of about 17 I started studying Bharatanatyam (*2) dance seriously. And then, after my physics graduation, I went to Chennai (*3) in 1982, telling my parents that I was going to study computer science. But I didn’t graduate, because from morning until evening I was studying dance. Finally, I decided to learn from Dhananjayans style Bharatanatyam dance and Kalakshetra style of Kathakali dance. And when I was in Chennai, I was also starting to work with a theater group and worked with Chandralekha (a group that performed Bharatanatyam along with other new forms of expression and became recognized internationally), and I performed in their work Angika.

- So, you weren’t content to stay with just traditional dance, were you?

- I was searching for a contemporary language. So, I was also working with an experimental theater company called Koothu-p-pattarai (*4).

So, 1987 when I was performing with the Dhananjayans and also with Kalakshetra, and by that time I did my first solo performance. It was a 2-hour performance by solo, and it was a packed house in Chennai and it received a lot of attention. So, some of my friends who came from London, they saw me, and they said I should really take up dance, learn contemporary dance.

Because I wanted to learn contemporary dance and I was searching all around, experimenting with theater, experimenting with Chandralekha, but I didn’t find an answer. In India at the time there was not even a context for contemporary dance works. Even Chandralekha, primarily her movement vocabulary is based on traditional material, she reformatted and reconstructed. Indian traditional dance had long evolved without contact with other cultures, so even if you had new ideas, when you tried to move, you still resorted to using the old methods.

And I thought, maybe I don’t have to discover contemporary dance. If there is a wheel existing already, I need to be able to use the wheel. So, that prompted me to go to London in 1987 to learn contemporary dance. - At that point were you thinking of becoming a professional dancer?

- Looking back, I don’t believe I was thinking about a career at that time. I got permission to study at London Contemporary Dance School (LCDS), Trinity Laban and Middlesex University, and I finally decided to study at LCDS. And while I was studying there, I began to do performances with friends and soon we were getting grants from the London Arts Board and the Arts Council that enabled us to start the Imlata Dance Company. I was the only Indian in the company.

- It sounds like an Indian name. What does Imlata mean?

- It comes from the expression, “I’m late,” because we had some members who were always late. (Laughs) And metaphorically also, because the contemporary exploration should have happened much earlier. This was around the time I first went to Japan, when we participated in the Japan tour of the World of Music, Arts and Dance (*5). We toured with some famous world music musicians like Baaba Maal, Youssou N’Dour, Khalid and the Sabri Brothers.

- What kinds of works were you creating at that time?

- Basically, we tried everything that came to our minds. We tried creating works with British artist friends working with us to show the physical language of Indian traditional dance, but it was difficult for us to understand each other’s way of thinking, so it wasn’t very successful. In that time in Britain, the Bi Ma Dance Company led by the Malaysian choreographer Pit Fong Loh was trying to present contemporary interpretations of Chinese or Malaysian traditional dance. Today there are artists like Akram Khan who have found success by introducing elements of traditional dance, but at the time the audience that could understand what we were trying to do was very limited. And of course, we did other kinds of works as well.

- During your time in London you got a Barclays New Stages Award.

- That was for the work Beyond the Walls for Men (1997). In London at the time, there were a lot of works dealing with the subject of gay sexuality at places like the DV8 Physical Theatre started by Lloyd Newson, and this was a work along those lines. It was a dance work that brought together traditional Indian dance movement with contemporary dance language.

From around this time I was getting a stronger desire to open a center for contemporary dance in India. Part of the reason I went to London was to find the knowledge and experience it would take to open such a center in India where there were no ready resources at all. So, at this point I ended my 14 years of activities in London to return to India and open such a center. - I would like to ask you about the activities you are engaged in at the Attakkalari Centre. First of all, would you tell us about the Attakkalari India Biennale festival that the Attakkalari Centre organizes?

- We began the festival because we thought that the best way to deepen the Indian people’s understanding of contemporary dance was to show the best of the most contemporary works. First, it was for a 3-day festival held in February of 2003. By the 8th holding it had grown to become a 10-day festival held from February 3 to 12 in 2017. There was Mandeep Raikhy from India, Tero Kalevi Saarinen from Finland, Marie Chouinard from Canada, and there were company performances from South Africa, Italy, Germany, Switzerland and South Korea, as well as showcases and film works, for a total program of 26 works. The 9th holding had to be postponed because of the COVID pandemic, but this year (2021) we are currently considering whether or not the festival can be held again at the end of the year.

- Besides performances, what other kinds of programs have you had at your Centre?

- We have had an international residency that provided five weeks of intensive training called FACETS Choreography Residency, and for young choreographers we had our Young Choreographer Platform, and we had performances of their results at the end. Also, with our South Asia Platform we have invited guests to talk with and then present performances of existing works and emerging choreography.

In the area of stage critique we held intensive joint workshops for writing on dance. In it we had arts writers from different backgrounds discuss about dance critique for the new era and have them write actual criticism. You know Ahnt Wasserman [ph], he used to be the Director of Ballett International, now Tanz, It is a German magazine, and he cooperated with us on this program.

As for our festivals, we get funding from Ministry of Culture, Government of India, the Department of Tourism, Government of Karnataka and the Indian Council for Cultural Relations among others. Besides these, we also get support from the arts councils of the various countries we work with. - We are told that your Centre has devoted considerable efforts in the area of dance education, haven’t you?

- In Bangalore there was a 3-day seminar held regularly on the theme of “physicality” that was under the sponsorship of Max Mueller Bhavans (the Goethe Institut named in honor of the German linguist of Indian languages, Max Mueller) that gathered about 10 noted artists of different disciplines. At the Attakkalari Centre, we held an “International Winter School in 1992 to which we invited artists from Britain in the visual arts, dance and theater, and from India people involved in literature, philosophy theater and dance, in order to learn from each other. We intended to hold the school every other year but, unfortunately it only lasted until 1994.

Presently, we are holding an educational program named the Diploma in Movement Arts & Mixed Media. Today there is a choice of a one-year course and a two-year course, but eventually we intend to make it a three-year course. In the course there is a comprehensive curriculum that students can choose from, including contemporary dance, ballet, body conditioning, Bharatanatyam, art history, anatomy, lighting design, traditional dance and more. In the Traditional Dance and Ethnic Performing Arts course students can study in depth such rare traditional art forms as Kootiyattam dance theater.

The annual tuition for the course is 20,000 rupees (approx. 30,000 yen), and for foreign students the annual tuition is set at 5,000 euro (approx. 650,000 yen). Many of the Indian dancers actively performing today have studied at this Attakkalari Centre program. - Do you also have outreach programs for schools and the like?

- Yes. We do programs for schools and for companies. In the old days, they used to ask us to do it for free because it would serve as good advertising for us. We said, “If you pay salaries to teachers or school staff, you should pay the artists as well.” We kept trying to convince them that if you don’t pay the artists, they can’t make a living.

As a result, most colleges and high schools in Bangalore will now hire dancers on good wages as instructors. Also, we have established a wide range of partnerships with companies like the Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) Hyderabad. We also do work for the National School of Drama and we do credit courses for Srishti School of Art and Design, National Institute of Fashion Technology, and many schools as well. Recently we have started a project we call Dance Excellence. We adopted four local schools and we selected children who are in the lower primary and upper primary school, say children up to 12 years of age, to give them training in dance free.

In this way, are actually building the or broadening the base of dance so that tomorrow there is an audience for dance, there are more people in dance. This is important. And I hope that if we can sensitize the government to the need for setting up something to support this, that will be good. - Hasn’t there been any opposition from the traditional dance world to your attempts to introduce contemporary dance? Aren’t there some who say that you are trying to destroy traditional dance?

- It is true that when the Attakkalari Centre was first established there was always this polarity, tradition versus contemporary. It is not that way anymore. Because many of the practitioners of traditional forms now also learn contemporary dance to make their vocabulary a bit stronger, their physicality stronger, their movement little bit more expansive and everything. And in fact at Attakkalari itself many of those traditional artists were there at our Centre.

But in the traditional arts themselves, like for example if you look at Kathakali, how it was created. There was no form like that. It was created by one person when he asked for this temple art form, Ramanattam to be perform in his palace, they didn’t allow it. So, he created his own art form. And the first performers of Kathakali were actually Kalaripayattu martial artists, because they already are trained bodies, so they started training them in Kathakali and that’s how the form was created. It borrowed things from Koodiyattam, Ramanattam, and other folk traditions and they were all put together in Kathakali.

In the same way the Bharatanatyam form we know today was only a formulation in the 20th century. Until then it was danced in the temples or there was the Vellalar community or some people called them Devadasis, and at that time it was called Dasiyattam of Devadasis, which means servants of God. Later there was a big backlash because of the British and they banned the dance form. But in the freedom struggle, the Indian National Congress, particularly also this Theosophical Society, Annie Besant, they all felt Indian tradition should be reclaimed and protected to create a sense of [national] identity. So, then they adopted this Bharatanatyam and renamed it as Bharatanatyam and then upper-class Hindus, the Brahmins took over. And then Bharatanatyam became quite prominent now in its present form because the upper-class people supported it. And when India became independent in 1947, they wanted to show the country’s identity, which led to setting up centers for classical dance. Then it received support from the new government. - So, we see that during their long history the traditional dance forms have changed and some have been discontinued, haven’t they?

- You could say, for example, that language of movement in classical dance is almost like a “golden box,” and sometimes the movements are perfected over many decades or centuries, so the vocabulary is very precise and perfect. And for an artist, the main focus is how to perfect this language so that you can fit in into this golden box. In contemporary dance, on the other hand, you need to have your own concept or theme or idea that you want to express, or you want to materialize. Then you need to create a language for that. That is the task of the choreographer or the dancer; all the language, all the things you create have to find a place [in your own box]. In the traditional forms of dance that has happened over centuries, what we call it is appropriateness. Certain things are appropriate for a style. But in contemporary dance, all the framework, has to be created by the choreographer and the dancers. And you need to come up with that thing so nothing will be out of place.

So, what I am saying is that once you have the historical understanding, if you have that very strong sense of authenticity, then you can journey through this. And in fact, many artists find outstanding language outside the traditional forms, but at the same time many also gain knowledge from tradition and find that it is one of the many streams. - At Attakkalari Centre, you are involved in research of both traditional dance and contemporary dance.

- Yes, we are. The purpose of this process should be to deconstruct [the history of the forms] until we come to a real conception of the principles of movement so that we can reformulate it. And we do this not just with the traditional forms but also with people like Bill T. Jones or Cunningham or Martha Graham, and earlier people like Isadora [Duncan] and all of that history. But we can only get an idea of this history by reading books or seeing some small amounts of video that exist.

We have gathered people doing joint research in various fields to find resources about traditional Indian dance from the intellectual, artistic, aesthetic aspects. we call it Nagarika (*6), which is a core research project.

Nagarika is the first attempt in India to approach the traditional performing arts using technological means, and it is now a integrated information system that analyzes and archives traditional Indian dance. We use film/video to analyze the movements of Bharatanatyam and Kalaripayattu from various perspectives. Because it is the mission of Attakkalari Centre to use the resources of traditional dance and contemporary dance and technology to create new performing arts, this [Nagarika] is one of our representative projects. - In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic in March 2021, a joint production dance project titled -scape¬ was undertaken by Attakkalari Centre and the Japan Foundation’s New Delhi Japan Culture Centre in India. The results of the project were then broadcast via the internet in Japan to high acclaim. I would like to ask you in detail about the contents of this work later, but before that I would like to ask you about the actual number of dance works that are created at the Attakkalari Centre.

- Since we spend one to two years on a work, with these large-scale works the total number is about ten to 12 works, I guess. Besides these artistic works, we are often called on to give performances of smaller commercially oriented works. These works give the dancers experience and help cultivate new audience.

The first major production happening at Attakkalari was in 2005 and 2006, called Purushartha. In this work, I actually worked with Japanese artists who I had met in Britain, Kunihiko Matsuo (media artist), Mitsuaki Matsumoto (musician) and Naoki Hamanaka (architect). I did the choreography and performed, and it was a very successful work that was a fusion of traditional dance, technology and contemporary dance. It got a lot of coverage in India as well. We toured with it to the Venice Biennale, the Munich Contemporary Dance Festival, the Morocco Dance Forum and other places, and we also did a performance in Yokohama.

We also have our resident Attakkalari Dance Company, but unfortunately it has been difficult to pay their salaries on an annual basis, so we now have to select dancers on a single-project basis. - At the Attakkalari Centre, you define your mission not only as the promotion of contemporary dance in India but also to serve as a base for linking to the world dance scene.

- One of the unique characteristics of contemporary dance is that it is an international art form. The principles and the techniques of movement deepen by being exchanged across borders. For Attakkalari Centre, helping to establish the foundation of contemporary dance and sending Indian dance out into the world are two wheels of the same vehicle.

And there is a famous saying from Mahatma Gandhi, “I do not want my house to be walled in on all sides and my windows to be stuffed. I want the culture of all lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet by any.” In other words, we shouldn’t take in any and all information and knowledge without restriction, but rather I would like to gravitate towards an evolving Indian identity so that the identity is not static. It can develop. Because we had that problem. During the colonial period, our development kind of stopped. So, we need to say on the one hand we have to access the knowledge and wisdom from our traditions but deconstruct it so that the concept and principles are excavated, not the outer form. And that is why with Nagarika we research our traditions, so that we can introduce new art and technology. - But don’t you think there is a generation gap when it comes to the way people view the colonial period? For example, I see young artists in Southeast Asia, for whom the colonial period culture is something from before they were born, and now they are using it in their pop culture.

- Like you say, the younger people only know the colonial era from movies and such, so I think they don’t really feel the weight of either the tradition or the colonial past. But I don’t think India has any kind of grudge against the colonial masters.

But an important thing is if you are not connected with your kind of roots in a way, like now the African-Americans are discovering their roots, and same way the British-Asian people are discovering their roots. And even in Korea, I saw that sometimes people are interested in looking into old language. But it won’t be the same as reviving the tradition and making it into a museum. It’s much more to use it in a way to develop the kind of a new sensibility, contemporary sensibility, because this is something precious you have. Whether it is Ayurveda (a healthy lifestyle system) or Yoga or any of the rituals and everything, there is a concept about the body. And if you have that then you can probably use it to learn ballet or opera as well.

Like for example, when I was first studying ballet and contemporary dance, all of a sudden there an Indian dance movement or a yoga position would come to my body that had studied Indian traditional dance. The traditional dance body is not mutually exclusive to the adoption of new types of movement language. It’s almost like when Picasso presented African iconography in his work and that made it became very contemporary.

I remember in Martha Graham, all of a sudden, an Indian dance movement or a yoga position will come in, and then later on you see how the influence from the time of Isadora to Ruth St. Denis, how Western dance was influenced by Asian dance forms. There are definitely Indian styles there. You will always find examples of traditions from one culture appearing in new styles in another culture. - Next I would like to ask you about young artists in India. Are they integrating things like hip-hop and technology in their work?

- The process of learning has changed quite a lot in the last few years. Now, many of the artists have their own personal learning process. So, people are learning from internet, video, people are learning from peers, people are doing workshops, and some courses they are doing. Of course, hip hop is becoming popular in India. And people also mix it with Bollywood, classical dance, folk dance. So, there is a huge amalgam of things are happening. Even though there is no support system for dance, actually activities of dance are happening quite in a big way. If you have a wedding, you have a choreographer choreographing things for both the bride and bridegroom, their families, and all of that. And on every occasion, there is something or other related to dance.

On the other hand, what is lacking is a systematic training and some support for a period of time to create really strong original work. When I was in the UK there used to be consultation by the Arts Board, Arts Council and all of that, and then setting up of national dance agencies. In France, for example, they have the Centers for Choreography, Centre Chorégraphique. Nineteen of them were set up during the time of Mitterrand. But such initiatives are not happening in India, many of the universities, schools are all setting up their own art centers. And some gated communities are also setting up their own theaters. But there is no policy for creating content and there is no policy for creating artists, how to train the artists, what are the opportunities for them. That is not there, and it is a problem. - You yourself studied in the U.K., and I would like to ask if there is a close relationship between India and the former colonial power in the contemporary arts in India today.

- In the field of contemporary dance, India actually has a stronger connection with Germany. Because Max Mueller Bhavan and Goethe-Institut, they played a big role because they made a conscious decision. Because German language is not spoken here, they could not bring theater and film that much, or literature to India. So, they felt dance was the medium they wanted to focus on, and they really supported dance.

For example, 1984 in Mumbai at the National Center for Performing Arts, NCPA, the first East-West Encounter took place thanks largely to the efforts of Georg Lechner, who as artistic director at Max Mueller Bhavan. It was a ground-breaking festival. I was in the UK at that time, and I remember, my company was invited to perform as part of that. I had the feeling at the time that it was the kind of program that an agency of the Indian government should have been organizing. - The “-scape” project was one that brought Indian and Japanese artists together to engage in creative work. In fact, I served as an advisor (and later a project member) for this project on the Japanese side.

- It began from a desire I had to have a chance for young Indian and Japanese and other foreign artists and staff to work together. When I had a meeting with the person in charge at the Japan Foundation’s New Delhi Japan Culture Center, we decided to have the artists come together at the Attakkalari Centre to work in residence for about three weeks in August and September 2020 and then perform the work they created at the Attakkalari India Biennale in February of 2021. And the plan also included holding other performances of the work in India and abroad. I visited Japan in February 2020 to see dancers at the Yokohama Dance Collection and TPAM, and I also had a meeting with you then.

But just after I returned to India, the COVID-19 pandemic began to spread rapidly, which made the residence work plan impossible. We had to think of an alternative, so we held a series of online meetings with the people involved. Eventually, we chose Ryu Suzuki as the Japanese dancer and Hemabharathy Palani (hereinafter Hema) as the Indian dancer, and because of the COVID ban on travel, the theme of the project became the fact that the two could not actually meet each other in person, and the search for a way to create a work under those conditions began.

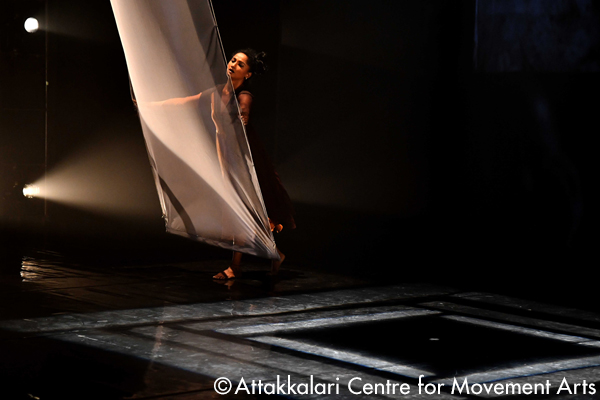

Then it became a plan in which a 30-minute film was made which basically dissected the existence of Suzuki himself (Performer: Ryu Suzuki; Filming director: Nao Yoshigai; Music: Tatsuki Amano) and we had it sent to India, and there Hema did a dance performance in response to the film. - Then on March 16, 2021, at 7:30 in the evening (India time) Hema first performed his dance at the famous Ranga Shankara theater in Bangalore and then the film [of Suzuki] was shown. And the whole event was broadcast online in Japan in real-time.

- The Attakkalari Centre’s is a small theater space, but the roof height is not very good. So, you cannot set up the lighting properly. It is very intimate theater space and we took COVID protocol precautions and we did lot of work during the lockdown time. In contrast, the Ranga Shankara is an excellent theater with a high ceiling. The tickets were mostly sold out for the event, and before the performance, I myself and the person in charge from the Japan Culture Centre got together and prepared an explanation of the performance and the film. For Indian audiences, this format for a performance is quite rare, so it drew a lot of interest. We had three Consul Generals from Germany, Israel, and Japan attend, and I think they were there with members from their consulates. And then a lot of artists and theatre people came. So, the response was good. But this was only the first phase, and when the COVID pandemic is over, we plan to complete the residence project, and then I want to see us tour around the world with it.

- Are there any other projects that are now in progress?

- We have been given a piece of land by the side of a lake in Bangalore. But we have to pay quite a lot of money to get that land. It’s 1.65 acres (approx. 6,700 square meters) of land. So, this is a beautiful location. We are now planning to build a “Center for Innovation in Performing Arts”, we call it CIPA, and it will have a couple of theaters and an amphitheater, plus several studios, so research facilities. It won’t be just for dance alone, but other performing arts also so that there could be a lot of transdisciplinary works and there could be some facilities such as a wellness part where body care system, martial arts and other things can happen. And then there would be also a restaurant, cafeteria, library, all kinds of things.

To realize this plan will require about 5 million dollars (approx. 5,5 billion yen) but we already have several people who are interested in providing funding. Unfortunately, we were about to launch a fund-raising campaign just before the COVID pandemic struck. So, the project funding efforts are suspended for the time being, but we definitely want to see the plan realized when the pandemic is over. So we have a second plan, which is actually not to build it all at once but actually start with smaller parts and gradually develop it all. - I would like to conclude by asking you what you foresee for the Indian dance environment in the future.

- India’s problem is that we don’t have an Arts Council and it is very difficult to get support funding on a yearly basis from the Ministry of Culture, and most of the theatres are just rental theatres with no curatorial functions. The situation at our Attakkalari Centre is that we have to depend on our income from workshops and performances and we do workshops, we do performances, and we earn some income. Then we invest to support the dancers, support the new productions, all of that. So, our situation is a bit like that of a circus living day to day really. However, Attakkalari Centre has a foundation of developing contemporary dance for 20 years now, and if we are able to complete our new CIPA facility project, we believe we can bring greater vitality to India’s performing arts scene.

When seen on the international scale, performing arts everywhere are facing crisis. However, in India since ancient times, the performing arts have always had the strength of being integral parts of our social and religious customs, so we believe they will continue to survive. True progress is not having a new house or car or having a plenty of money in the bank, but rather it is increasing the number of wonderful “experiences” you have. That is exactly what dance and theatre are about. We have to value our experiences. And I believe that we have to consistently learn from the changes that are taking place over time, and then turn that knowledge into action.

Jayachandran Palazhy

Attakkalari Centre’s Aims

As a Base for Contemporary Dance in India

Jayachandran Palazhy

In India, where traditional dance is such a strong presence in the performing arts, the Attakkalari Centre for Movement Arts in the Bangalore state in southern India has stood as a pioneering gateway to the field of contemporary dance. The founder of this Centre and its artistic director is Jayachandran Palazhy. The Centre has built a network with overseas organizations, launched the Attakkalari India Biennale, while directing efforts to creation including artist-in-residence programs as well as educational programs, all of which has won high praise internationally.

Interviewer: Takao Norikoshi (dance clitic)

Attakkalari Centre for Movement Arts

https://www.attakkalari.org/

*1 Bollywood

The nickname of the Indian film industry center in Mumbai. A name combining parts of the old name for Mumbai (Bombay) and Hollywood.

*2 Bharatanatyam

Bharatanatyam is one of the four forms of traditional Indian dance, along with Kathakali, Kathak and Manipuri. Bharatanatyam dance originated in the temples and court of Tamil Nadu in southern India and is considered the oldest of the four main dance forms.

*3 Chennai

Chennai is the capital of Tamil Nadu state. It is the birthplace of the Bharatanatyam dance form, and it was here that Rukmini Devi Arundale (1904 – 1986) founded the Kalakshetra academy for dance and music in 1936. It is also the city where the avant garde dancer/choreographer Chandralekha (1928-2006), who began from Bharatanatyam and fused it with modern dance expression to open up a new era in Indian dance, was based.

*4 Koothu-p-pattarai (KPP)

Founded by the playwright Na Muthuswamy in 1977. An avant garde group based in Chennai that sought to both preserve and build on traditional theater. It placed importance on physical language based in dance and martial arts.

*5 World of Music, Arts and Dance (WOMAD)

A world music festival started in 1982 by Peter Gabriel. In Japan, beginning with the opening of the Pacifico Yokohama facility in conjunction with the development of the Yokohama Minato Mirai district, the WOMAD Yokohama Festival was held for five years beginning in 1991.

*6 Nagarika

Derived from the Sanskrit word meaning ’a civilizational dimension,’ Nagarika is an integrated information system on Indian physical traditions through technology and is the first such initiative in India in the field of traditional performing arts. Based on long years of research on Indian traditional dance at Attakkalari Centre, and with support from the Daniel Langlois Foundation, the Goethe Institut and the Ford Foundation, it has created videos about Bharatanatyam and Kalaripayattu. Movements, etc., are analyzed and recorded on video, commentary is added, and interactive methods are used to enable viewing of the movements from various vantage points, including straight on and from the side.

https://nagarika.org/attakkalari

-scape

(Mar. 16, 2021 at Ranga Shankara)

Related Tags