- May we begin by asking you about your first encounter with dance?

- From the time I was a child, I attended the Associação Cultureal da Casa Velha (*1) and I danced with the Companhia de Dança Tradicional Mascara, doing folk dances of southern Mozambique. From around the age of 15 or 16 I was also a member of the theater company Produção Olá and performed there as an actor. Casa Velha was a wonderful place where a lot of arts and cultural activities went on, although it doesn’t exist like that anymore. I would say that I am what I am today thanks to Casa Velha.

- Would you tell us more about the cultural center Casa Velha?

- Casa Velha had a theater and a library with a great variety of books and magazines and there were workshops held in a variety of fields, such as for people who wanted to learn to take photographs or how to become an actor. So, it wasn’t just for dance and theater, there were a lot of cultural activities going on there, and I attended activities there very often Casa Velha. There were many small groups with everyone actively learning from each other. I even taught young children how to read and write there.

One unique thing about Casa Velha was that it had a category of “work” activities. The first time I ever earned money was working as a clown there. At Casa Velha we made a clown group that would go to perform at children’s parties and the like. You might say that those activities were the starting point of my career.

The Casa Velha building was provided by the government but the Casa Velha Association that ran it was a non-government agency that was supported not by the government but by organizations from many countries. And for a very small monthly fee, you could become a member and participate in a variety of activities. It was also a place that welcomed not only the members but a broad base of people. - Would you tell us what it was that got you interested in contemporary dance?

- The fact is that I have never done contemporary dance (laughs). I actually entered the world of contemporary dance by doing stage lighting work. As I was performing as an actor with the Casa Velha theater company Olá, I became more interested in the technical side of staging a play than in the plays themselves. I began to think that I wanted to help make the stages more creative and the staging better. At the time I started acting in plays there was no stage lighting and the works were just performed in a dark “black box.” So I thought that I wanted to begin by improving that situation, and I began teaching myself about lighting.

From 1997, I went to Portugal on a grant and studied stage art for three years. After I returned to Mozambique, I began working as a freelance lighting designer. After working with a variety of theater and dance companies and choreographers, I started working at the Franco-Mozambique Culture Center (CCFM) (*2) from 2005. By the way, I was the first Mozambique native to work on the lighting staff at CCFM. The, in the process of working with a number of stage directors there, I became attracted to the world of contemporary dance. The reason was that it gave me an experience of true freedom and rich creativity. I think I felt this so strongly because I had begun my career in traditional dance and theater, but here was a new world of creative freedom with no traditional rules. It was a world that truly made me feel free.

Also, as I worked at CCFM I became interested in the fields of management and production. So, when the Instituto Superior de Artes e Cultura (ISArC) opened as Mozambique’s first arts university, I studied arts management there and began to think about how to create an environment that made where arts organizations could function easily and more effectively. - When did contemporary dance begin to become popular in Mozambique?

- I couldn’t give you a clear answer about that timing right here and now, but I believe it was in the latter half of the 1990s when choreographers like Augusto Cuvilas (*3) and Maria Helena Pinto (*3) were active at Companhia Nacional de Canto e Dança. They were active at the national company for song and dance for a while and then began to work on their own projects after going independent. After that appeared the choreographer Panaibra Gabriel Canda who is now a leader of the Maputo contemporary dance scene. These three choreographers each started a school and many young choreographers began to study and emerge under them.

Then in 1993, a contemporary dance project named Danças na Cidade (*4) was launched in Portugal to gather dance artists from around the country, and within that a dance community for artists from all the Portuguese speaking countries named “Dançar o que é nosso” was formed from within that in 1998. I think that was very important for promoting creative exchange. This project changed its name to ALKANTARA (*5) in 2005 and it continues today.

Today’s Dance in the Cities was a project that began in Portugal, but Mozambique’s cultural organizations were also involved in it. It contains a project for nurturing choreographers, and many of the young choreographers have been invited to Maputo. By the way, I was in charge of the technical program at the time and that is how I was involved in Dance in the Cities. Projects like this eventually helped to nurture more young choreographers. - Would you tell us more about the Companhia Nacional de Canto e Dança where the choreographers that went on to spark the contemporary dance movement were active?

- The Companhia Nacional de Canto e Dança (National Song and Dance Company of Mozambique) was formed by the new government after Mozambique became independent. When Mozambique was a colony of Portugal, the different ethnic peoples were governed separately. So, just after independence, one of the issues the Mozambique government faced was relieving tension between the ethnic groups. So, one of the first things the government did was to form the National Song and Dance Company of Mozambique and make it a company to gather together people from all the regions and ethnic peoples so they could perform all the ethnic dances.

People of one ethnic group were surprised to see that members from of different ethnic groups could also dance the dances that they thought were theirs alone so skillfully and beautifully. Also, when people saw that the productions created by the national company included elements from various different ethnic dance traditions, they realized that the national company belonged to all the peoples of Mozambique and that, by extension, they felt a sense of identity in that that the country of Mozambique itself belonged to all the people. The national company played an important role of helping to relive tensions between the ethnic groups and bring the hearts of the people together.

However, today that former role of the national company is finished, so it seems like they have lost purpose to some degree. It looks as if they are looking for a new course and wondering if they should stay with ethnic dance or move forward in more contemporary directions. - The National Song and Dance Company of Mozambique also creates productions of bailad (*6) dance theater (also referred to as African ballet) that combines elements of Western performing arts. Is there a connection between this bailado and Mozambique’s contemporary dance?

- Bailado and contemporary dance are completely different. In the National Song and Dance Company of Mozambique’s bailado they seek group-oriented expression. On the other hand, in the world of contemporary dance, importance is placed on the individual and it reflects the consciousness and intentions of the individual. In my productions, and in the works of many contemporary dance choreographers around the world, it is the inner depths of the individual that is focused on. For example, if I select you in an audition, it is probably not because you dance skillfully but because you project some kind of energy or the uniqueness of your point of view or thought. In the world of contemporary dance, the dancer is expressing the individual, not a group.

- Is contemporary dance connected to ethnic folk dance in Mozambique?

- It is connected to both ethnic dance and theater. We are asking ourselves who we are, and what makes us different from others. Using these elements related to our identity like ethnic dances and customs in our contemporary dance is the same as revealing out nationality and our ethnic roots. In other words, we are expressing through parts of, fragments of our traditional culture in our contemporary dance. In that sense, we can say that contemporary dance is inseparable from our ethnic dance and plays. In fact, in much of Mozambique’s contemporary dance, movements from ethnic dance and our unique musical culture are used as expressive elements.

Also, many dancers do ethnic dance as well. The reason for this is that for many contemporary dance projects the dancers are gathered by going to the ethnic dance companies to recruit dancers. Of course there are also people who start out in contemporary dance from the beginning. - I would like to ask you about the Kinani festival now. What is the meaning of the word Kinani? Also, would you tell us what led to the start of Kinani?

- In the language of southern Mozambique Kinani means “Everyone dance!” When I was working at CCFM, I made a proposal to its president at the time, Jean Michel, in 2005 that we join together to launch the Semana da Dança program that would become the forerunner of Kinani. At first, this Dance Week program didn’t take the form of a festival. It was just a situation where I said, “Why don’t we make this week “dance week”? And the answer was, “Great, let’s do it.” After a while we were holding a Dance Week once a year at CCFM as a regular event to which we invited lots of dance groups to perform over the course of the week. It wasn’t just groups from our country, we also invited French theater companies that CCFM had relationships with. When I quit my job as the lighting designer at CCFM, the program was continued under the new name of “Platform Kinani” (details explained below).

- Would you tell us how you drew up the program for Kinani I?

- “Platform Kinani was held every other year, and in the alternate year the TRIDISCIPLINAR contemporary arts festival or Dança da Semana (Dance Week) was held. The TRIDISCIPLINAR was a program aimed at promoting exchange between artists in its three main disciplines of dance, drama and music. The artists exchanged ideas and do performances without deliberately telling the audience beforehand what they would do. As a platform for experimental work, they do performances in places like the library, or on the street, etc.; they try performing at a variety of places and hold discussions. In many cases, the things that are discussed there give birth to the theme for the next Kinani festival, and that theme in turn determines what we choose for the program to include. By the way, these themes are things that we share among ourselves and we don’t make any particular effort to announce them publicly.

For example, the theme for the 2017 program was “Identity.” And the reason for that was that at the 2016 TRIDISCIPLINAR we had discussed the place of traditional forms of expression in the contemporary arts. But, there is a need to consider what the meaning of the word “tradition” actually is. When we say “tradition” the first thing that comes to mind for many is ethnic dance, but when we use the word tradition, it is not necessarily limited to ethnic dance. It means everything from the style of clothes we wear to the way we talk to our common gestures. And we want to say that it is not your ethnic traditions but everything from tradition that has become a part of you. - From that 2017 Kinani based on the theme of “Identity” you did a collaborative project with the ethnic dance company Associação Dança Cultural HODI of Maputo that drew a lot of attention I hear.

- I was a collaboration involving the Associação Dança Cultural HODI members and two contemporary dance choreographers and it resulted in a performance titled “Theka.” Theka is the word(s) ethnic dancers of southern Mozambique shout out when they are dancing and find a rhythm. The purpose of this project was to think together with the ethnic dance company about the meaning of “expression.” The dancers and the choreographers are positioned in the two different worlds of ethnic dance and contemporary dance, and we wanted to see what would come out when searched together for a new method of expression. The result was about a 45-minute work and musically, in addition to the usual programmed music, live performance by traditional drums and marimba (wooden xylophone) became the main music component, which produced a very innovative effect.

The thing that led to this project was the experience of co-organizing the 6th Kinani in 2015 with the most influential platform in African contemporary dance, the Danse L’afrique Danse (*7) program. At that festival we had contemporary dance performances from various parts of Africa. As a curator I looked at them and felt that methods of expression used in African contemporary dance was based on similar aesthetic values to those of the West and was progress in the same direction. I thought that was strange. Because, many aspects of our culture, forms of expression and customs are different from the West and that should naturally be reflected in our dance. I couldn’t stop thinking about this issue, so I decided to make artistic expression related to identity the theme of the 2017 Kinani festival.

So, in the collaboration with the ethnic dance company that would introduce traditional elements, it was an attempt to have them experience anew that they have their own unique rhythms and modes of expression. Now, this project is getting attention internationally and plans are in place for performances in Germany in June. Personally, I would like to recommend that other choreographers and dancers try using traditional music in this way. I would like people here to think not about creating works in pursuit of what they refer to as “sense of beauty” or “high levels of artistic perfection” in Europe or Asia, but to take instead the question of “Who am I” as their starting point. I think that can be a first step toward making a contemporary work of art with one’s own mode of expression. - In the results of this experiment have you seen that you might call originality in contemporary dance in Mozambique?

- I don’t like to think in terms of the theme of originality artistic expression in Mozambique or originality of artistic expression in Africa. I choose the perspective of seeing things from the perspective of people living in the contemporary world. We are already being influenced by a variety of things from around the world; from Africa, Asia and Europe. There is always something influencing us. In the project with the ethnic dance company, it wasn’t Mozambique’s originality that we were searching for. What we sought was to communicate to the world who we are.

- What kind of influence has Danse L’afrique Danse had on the contemporary dance of African countries?

- Through Danse L’afrique Danse we were able to get an understanding of the overall direction of African dance, and we were able to get a global perspective. I believe that the audience, too, was able to get a vision of where Africa stands in the world of contemporary dance. Also, from an artistic standpoint as well, it has led to a lot of collaboration and artistic exchange and given birth to new projects. For example, it was through this platform that we met the young choreographer Judith Manantenasoa from Madagascar and decide to do the production for her company’s work

Métamorphose

. We are planning performances of this work in Europe and other African countries, and Kinani will be doing the promotion.

In this way, we have invited artists discovered through Danse L’afrique Danse to our own country numerous times for residencies to create new works. And many of the resulting works have then toured Europe and African countries. In addition, we have done things like collaborative projects with choreographers from Mali and South Africa, and there are also many projects that have resulted from encounters between the artists themselves. - You are also involved in the creation of works at Kinani, aren’t you?

- That is a question that I must answer with both Yes and No to. We are involved in the creation of works, but it is not for the purpose of presenting them at the Kinani festival. For example, when we started Theka , we didn’t know whether it would become a production that we could present performances of. All we did was to bring the artists together and then waited to see what would come of it, what they would be able to give birth to. We would have been happy if it led to nothing more than some serious discussion. At Kinani we have residencies, we support creative work and encourage exchanges and mount displays, etc., but we have never created works for the purpose of presenting performances of it. If our dream of someday having our own studio ever came true, I would first of all like to use it for experimenting with various things. We would use it to enable the artists to experiment with ideas they have, without concern about whether it would lead to performances at Kinani.

- Kinani has used old unused buildings or buildings abandoned before completion as festival venues. Why do you use venues like these instead of theaters?

- For TRIDISCIPLINAR, the question arose about what spaces could be used to artists to create their works. Since we don’t have our own studio, we tried using unoccupied buildings. This decision was also like a form of suggestion to the government. We wanted to show them that artists need places to work and that art is necessary for the communities and society at large. People go to theaters to see works performed, but there is consciousness about where the works are created. We used abandoned buildings because we wanted to make people think about spaces where art can be created, but it was not in order to say that we necessarily needed a building with the necessary facilities. Rather, it was to show that these kinds of abandoned buildings could be converted into spaces for artists to create art.

- What kinds of people are your audiences made up of?

- When we first started the Kinani festival, the audiences were mostly foreigners. So, one of our first objectives was to increase the number of local people in our audiences. We wanted to change that situation where the audiences were mostly only foreigners during the festival week; we wanted to get more local students to come to the performances too. The first thing we did in order to attract students was to get permission for dance groups participating in our Kinani festival to use spaces in high school facilities in Maputo for their practice. First we had the groups create their works and then practice them at the high schools. And once a week, we had the groups do open practice sessions for the students to see.

After watching the practice, the students were invited to participate in a question and answer session with the dance group. The students asked the dancers and choreographer questions like what contemporary dance is and if some particular movement has a specific meaning, so they were able to discover for themselves things about what contemporary dance is. This experiment led to a movement for the students themselves to form a new contemporary dance group. Also, ones who became interested as a result of this program came to see the Kinani performances. By continuing this audience-building program for a year, we were able to get many Mozambique natives coming to our performances. - When did you begin this audience-building program?

- From around our third holding of the Kinani festival. Even if we succeeded in filling the theater as a result of that program, however, we felt that its effect wouldn’t last long. So I thought we should try to nurture more young people who would go on to think about contemporary dance for the future. In other words, we wanted to get participants who would become the next generation of dancers and choreographers. However, we only conducted this audience-building program for two years. The reason we discontinued it was partly because of the cost, but we also felt that it had achieved its purpose. Because of that program, we were able to get the audiences curious and wanting to know what would happen at the next Kinani. So, in order to cultivate their curiosity and live up to their expectations, we continue to strive to introduce something new each time.

- It seems that you have a strong connection with Europe, but are you also thinking about exchanges with Asia?

- Yes. I want to see us do exchanges with countries in Asia. Because, I believe the countries of Africa need to get to know the whole world. We don’t have much contact with the dance companies of Asian countries. When I tell artists that I met in Japan that I am from Mozambique, they would hesitate and say, “OK …,” and it would be followed by an uncomfortable silence (laughs). Then I would always have to explain that Mozambique is a country in southeastern Africa. This situation always makes me impatient. But we always have the potential to learn from each other through the arts. I think that we should make more use of this potential in the future.

For example, we can learn from each other through artistic exchange by inviting Japanese groups to Mozambique. Through exchanges like this we can learn about an expanding world. Seeing each other’s artistic expression and think about the messages the other is trying to communicate, we can find mutual things in common and through that we can realize that we are not that far from each other. That’s why I think it is best for us to have more exchanges with Asia. - What is the attitude of the people of Mozambique toward the arts.

- Mozambique is a country that is presently full of societal issues, but the arts are not a means to tackle those problems, it is what offers them a shelter from the troubles of life. When people have worries or troubles, all they need to do is put on some music and in a minute they will be dancing and forget their troubles. That is why commercial music and the popular music industry are booming. And the artists who make music that the people can enjoy are very well known. So, all of the government’s economic support and budget goes to popular music. Much of that can help the people forget their problems but it can’t open people’s eyes to the solutions.

- The arts you seek are completely different from that, aren’t they?

- Yes, completely different. So, we don’t get any of the government’s economic support. Our art is for the purpose of knowing and discovering truths. Our kind of art is very important, but it is very difficult to get economic support for it. So, in fact there is more time spent on discussion of how to get financial support than on making art. For us, CCFM is our only source of financing. It covers our international activities but it can’t cover support for our local groups. We would to concentrate on creating art, but to be honest, we have grown tired of trying to find people to support our work.

- Could you tell us if you have any plans yet for the next Kinani festival?

- There is one thing I have decided. In order to promote discourse about the common people at large, I want to have dance performances of contemporary dance works at a large venue like Maputo’s Independence Square. Dance has always been performed at closed venues, in venues that don’t have a feeling of openness, but next time I want to be able to perform in front of the masses at a venue where large crowds can gather.

- We look forward to seeing that 2019 Kinani festival. Thank you so much for giving us your time for this interview.

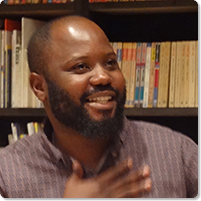

Quito Abrao Tembe

Mozambique’s Emerging

Contemporary Dance Scene

Quito Abrao Tembe

Initiator of Kinani Festival

As a multiethnic country with a large immigrant population located in the southeast of the African continent, Mozambique has a rich culture of ethnic dance. In the 15 years of socialist reform and governance following the country’s independence for Portugal in 1975, the performing arts were promoted as a means to build national spirit and awareness, and since the nation’s democratization around 1990, a dynamic new wave of creators has emerged. In 2005, the international Kinani Contemporary Dance Festival was launched in the capital of Maputo. Kinani aims to promote contemporary dance and nurture young choreographers, and it uses as venues not only the theaters in the city but also buildings deserted in the middle of construction and ruins.

Interviewer: Mayako Koja

*1 Casa Velha is a building built in the colonial period, and after independent the journalist Machado da Graça, with the support of many figures in the arts and culture, to make it a center for the arts and culture, focusing primarily on theater and dance. Today, the building is preserved as a cultural asset.

Casa Velha Photo: Mayako Koja

*3 Choreographer/dancer for the National Company for Song and Dance. Have experience studying Cuban dance.

*4 https://www.alkantara.pt/sobre/historico/

*5 ALKANTARA is an organization based in Lisbon Portugal that organized the biennial ALKANTARA Festival. Its activities include programs for nurturing artists, presentation of works, residential art programs, arts-related surveys and research, international exchange and more.

http://www.alkantara.pt/

*6 Bailado is a Portuguese word for Western ballet. It is used today for a new type of dance in Africa that combines Western performing arts elements with ethnic dance and music with a narrative element. Usually it is performed by a few dozen dancers and several musicians performing on traditional African instruments (mainly drums, timbila and marimba) but employs no spoken narrative. The main expressive elements are the dance and pantomime. In the French-speaking African countries it is referred to as African ballet.

*7 Danse L’Afrique Danse was launched by Institute Français in 1995 and has been the largest contemporary dance platform in Africa. It is held alternately in different countries around Africa. Besides performances there are exhibitions, discussions, interactive sessions and exchange programs. The main sponsors are Instituto France, Total among others.

Performance in Kinani

Photo: Yassmin Santos Forte

Kinani

Kinani is an international contemporary dance platform dedicated to the spread of contemporary dance and the nurturing of young choreographers. It is held every other year in Maputo in October with a roughly week-long program of events at venues around the city. For each holding about 30 companies from different countries are invited, for a total of about 100 artists. In 2017, 50 choreographers from 14 countries participated, presenting performances of 25 works. The venues included CCFM, Teatro Avenida, Museu das Pescas, Espaço alternatevo 4ºandar and more. The main supporting organizations are Instituto France, Camões -Centro Cultural Português), the Swiss art council Pro Helveita, The Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, Fundo para o Desenvolvimento Artístico e Cultural (FUNDAC) and Europcar.

https://www.facebook.com/kinani.moz/

Performance in ruins

Photo: Chico Carneiro

Related Tags