- Could we begin by asking you about your personal history? We have heard that you were interested in dance as a child.

- The school I attended was a unique one that had dance classes separate from the physical education classes. So, I was doing creative dance from the age of seven and continued it through high school. I like working with my friends to create dance pieces for festivals and performances. And in my teens, that was like my real reason for going to school.

- I have heard that at the time your dream was to direct an Olympic opening ceremony. It would be normal to want to become a dancer, but why would your dream be something like directing an opening ceremony?

- I liked physical expression and performing arts, but I didn’t have any real desire to become an actor or dancer, instead I had a vague idea that I wanted to move in the direction of stage art design or directing. But, among the various genres in the performing arts and theater craft, I wasn’t able to find the field I wanted to pursue. Near the end of high school when it came time to decide what course of study I would pursue, I just happened to see a TV broadcast of the opening ceremony for the 1994 Winter Olympics at Lillehammer. The impression it gave me was one of a magical world with people of all ages and nationalities coming out to perform on the pure white snow like fairies, and I knew intuitively, “This is what I want to do.”

- The university you chose was not one known for performing arts, but the Tokyo Zokei University of art and design.

- What I wanted to do was not something that was taught at any university’s existing department or something that I could learn by entering any particular type of company. So, after doing some serious research, I decided to enter the Comparative Art and Design (zokei) course at Tokyo Zokei University. In general terms it was a course for studying arts management, and I thought it would be the best way to get a comprehensive overview of the different fields of artistic expression.

During my university years I was also involved in the launching of a student theater company at Waseda University, where I did things like designing spaces for performances, and I also registered as a part-time employee with an event production company, through which I worked at sports events that attracted audiences in the tens of thousands. As I was doing these various things, I felt that I was somehow getting closer to that opening ceremony I was dreaming of (laughs). When Japan hosted the Nagano Winter Olympics in 1998. I worked as a volunteer and was involved in the operation of things like ceremonies held in the athlete village and cultural programs.

Working in theater at that time, I came to feel that creating and performing theater works inside a theater wasn’t my style, so I quit the theater company and started working on projects that were open to the general public. And, after graduating from university I made my living by working in an event production company and used the money I earned to finance my own projects repeatedly. After that, I suspended my projects for a while and worked in a mail-order cosmetics company, where I worked on product direction and planning. While doing that I saved up my earnings and used that to go to graduate school in Italy at Domus Academy. - How did you decide where to study overseas?

- I happened to go to Europe for the first time on our university’s graduation trip. We visited Spain and Portugal and I was impressed by the culture that you might call the “slow life” I saw there, with people enjoying the richness of life. At first I thought of studying at Fabrica in Italy (the art school that Benetton started for young creators). In a book based on discussions between Shiseido’s honorary chairman, Yoshiharu Fukuhara and the chairman of Benetton, Luciano Benetton, titled “Dialogue – Things that Have Been Important to Us” there was talk about a form of company that valued slow life and eco-friendliness, and that made a deep impression on me. But since I was very close to the 25-year-old age limit for students and also due in part that the Fabrica president, the photographer Oliviero Toscani, had just left the school, I decided to study at the Domus Academy also in Italy.

- What kind of a school is it?

- It is Italy’s oldest university graduate school for design. It only has a Master’s course. It is like a research institute for people who have already started their career in design. There, I entered the newly established business design course. It is a course where you learn about designing the overall structure for a business, and if an MBA is a Master’s degree in business management, our course was one where you learn how to design the structural scheme for a business.

I entered in the course’s second year and the classes were project-based with a practical curriculum by which we would formulate proposals for a variety of different kinds of subjects the school received from corporate clients. The orders came entertainment companies and establishments like a famous old shoe merchant. There were almost no Italian students there, so we were working together on projects with students from different countries with different language and cultural backgrounds. If it were a matter of designing products that wouldn’t matter so much, but since we were talking together to try to draw up proposals for business model designs, the difference in levels of the business in the different countries the students came from made it really difficult. - How long did you study at Domus Academy?

- It was about 14 months. I really wanted to stay longer but the immigration policies were very strict and I couldn’t get a visa extension. But there were a couple of Italian companies that placed orders with me, so after that I was going back and forth between Tokyo and Milan. One of the companies was a design office that did business designs for corporations and another was a company that was started by sociologists at a future concept lab to do surveys on social trends. It was a company known for its “creative marketing” method that used an international network of young researchers they called “cool hunters” to research a variety of social trends around the world. I worked for them as the researcher in charge of the research on Japan.

- That suggests an amazing capacity for action (laughs).

- From childhood it seems, I never had any hesitation about contact with things foreign or doing things with people from different cultural of social backgrounds. I believe it was that inherent love of that kind of contact that started me on the course I have taken in my work.

- After this period, when was it that you got back to doing the projects open to the general public that you originally wanted to do?

- To make a living, I continued the work from Italy and as I gradually got a firmer financial base, I applied for the 2009 Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial and began activities in that direction again. Think that I wanted to do a general public participation project, I shot a movie called “Shutters 4.” It was filmed on the commercial street of the town of Tokamachi and I brought together film specialists including a scriptwriter. Renting a house on the street to serve as a working base and living there during the filming, I was able to get about 300 local citizens involved and put together a film of about 70 minutes in length.

Rather than being the director or doing the camerawork, you could say that I acted as the planner, and while living in the town I worked to convince the local citizens to get involved (laughs). Sort of like a person in charge of communication. - That job you describe just now of convincing people to get involved seems connected to the work you are doing today. Was the next thing you did after Echigo-Tsumari, the “KAMIYAMA PhilFARMony” (“Kamiyama Nokyo Gakudan” a title that plays on the pronunciation of “No-kyo” with the character for Agriculture [No-gyo] mixing the character for Philharmonic Orchestra [Ko-kyo]), done in the town of Kamiyama in the mountains of Tokushima Prefecture?

- That’s right. I wanted to do another work because there were some things that I felt I had left undone in the Echigo-Tsumari project. Just at that time I happened to get word that former STOMP (*1) member Rick Willett had retired from the group and wanted to come to Japan, so I was thinking that if we could get people from a town somewhere in the mountains to get involved and use things from the town, we could do a STOMP-like performance. And when I was looking for a town to join in the project Kamiyama volunteered. It was when I was working on the preparations for the project that I found out about my illness. (This project, titled “ Kamiyama Nokyo Gakudan ” [KAMIYAMA PhilFARMony] would be the first project she did after returning to work after treatment for her illness in 2011.

- In 2010, at the age of 32, you were diagnosed with malignant fibrous histiocytoma in the cartilage of the right leg. You had three operations and eight chemotherapy treatments during your period of treatment and completely lost lower limb function in your right leg. As a result of this ailment and disability, we have heard that it changed your approach to life quite significantly.

- Yes, that is true. Until the ailment, I feel that I was rushing head-on toward dreams that I had no idea whether or not could ever be realized. I decided that now I had to completely reset my way of thinking and acting. Mine is a type of cancer with a very low survival rate, so I have to concentrate now on staying alive. I decided to stop thinking about dreams that could be realized in maybe five or ten years and focus on enjoying life and work in the here and now. That was a big shift.

- On the other hand, your disability has also resulted in numerous new encounters. One is the Yokohama Rendez-vous Project that was launched as a program of the Yokohama municipal facility Zou-no-Hana Terrace that combines an arts space and rest house (operated by Spiral/Wacoal Holdings Corp. Art Center on consignment from the Yokohama Culture and Tourism Bureau). You began working as director of product development conducts in collaboration with public welfare facilities in Yokohama as part of the same project from 2011.

- Just at the time I had returned to work after my period of treatment and recovery, the Senior Planner at Spiral Tomoharu Matsuda who had planned the Rendez-vous Project made me an offer, saying he had a perfect job for me. Originally, I had wanted to creating things that were more intangible like performance rather than products, but now I had lost everything and I felt that if there was something, anything I could do now I would be happy to do it, so I took the job.

- Can you tell us specifically what the work involved?

- Before I became the director, Matsuda-san and Tsutomu Okada-san (Spiral Senior Curator) had been sending artists to welfare facilities to make lots of interesting products based on creative ideas. But, when it came time to sell them, they were not in a position to distribute them because of problems involving sales networks, cost rates, packaging, etc. So, it became my job to do the branding work to make the products sellable. Getting an art director involved, we decided on the brand name of Slow Label (*2).

- Recently, original goods created for the Slow Label brand are being sold in department stores and boutiques around the country, and since 2012, the general public participation type monozukuri (product creation) program Slow Factory has also spread nationwide.

- With the Slow Label brand platform that brings people with disabilities and artists together to engage in creating products, the better sales go the more problems arise in terms keeping up with production demands, and in that sense we have seen the platform’s limitations as a “slow” lifestyle endeavor. When department stores and boutiques start selling the products they say they like the “slow” concept, but when it comes to signing sales contract we often have to be able to guarantee lot sizes, to meet deadlines, etc. in the same ways as with mass-produced products. That conflict of interests and concepts can make things difficult for both sides. The fact that depending on welfare facilities alone for production would not be sufficient led to the idea of the Slow Factory, where the materials and tools would be taken to Zou-no-Hana Terrace where people from the general public could also help with production, by in effect turning Zou-no-Hana Terrace into a sort of Slow Label Factory.

We made Slow Label aprons and had everyone who came to help out at the factory wear them and had a variety of different people do the kinds of work—other than packaging for example, which anyone can do—that maybe people at the welfare facilities could all do. That was how the Slow Factory platform started. And once we started this we found that everyone really enjoyed participating in the work. People like monozukuri , they like doing work where they don’t have to think about anything and just use their hands to make something, and it seemed that many were really seeking that kind of work and enjoying it.

This made me think that perhaps, rather than selling products, we might be more successful selling this [ monozukuri ] “experience.” People with disabilities are not thinking of making things in order to sell them and make money, but rather they are thinking about ways to connect to society, and it is that kind of experience that gives them real enjoyment. I began to think that if people with disabilities and people without can work together to make things, that alone is sufficient to make it meaningful as a project. And I feel that way of thinking led gradually to a shift, toward activities like the Slow Academy study program, etc., aimed at creating opportunities for people with disabilities to come together with people without disabilities. - Has the fact that you yourself are disabled had any effect on your activities?

- The fact that I walk with a crutch helps remove barriers, and it makes a situation where people at welfare facilities always receive me with real warmth. If I weren’t disabled, there would perhaps be times when I would be received as an outsider, someone different from them. Also the fact that I have a disability but am still very active (laughs) means that they can’t use their disability as an excuse for not doing things. And for me myself, I think it would often be very difficult for me if I were working on a normal corporate project, but the fact that I am now in an environment where we can naturally take into account each other’s positions is something I am grateful for.

- It seems that in your life there have been many positive connections and results coming from your various experiences and encounters. It appears that the things you have felt and the issues you have identified in each of your activities have led to a foundation for your next project.

- Well, yes. The Slow Label activities then connected to the Yokohama Paratriennale arts exhibition that we launched in 2014. With the monozukuri (product creation) projects, of all the people in the welfare facilities, it was only the ones who had the necessary skills who could participate, and that made me think that if it were art projects we could do things in which everyone could become involved in some capacity. That led me to propose from my position at Zou-no-Hana Terrace in the same year of the Yokohama Triennale that we organize the Yokohama Paratriennale 2014 (*3) as an exhibition to bring together people with disabilities and professionals from various genres. Before that I had been working with the Yokohama Culture and Tourism Bureau, but this gave me the opportunity to work also with the Health and Welfare Bureau and led to the establishment of Slow Label as an NPO.

- Wasn’t the holding of the Yokohama Paratriennale something that also connects to your original dream of directing an Olympic Opening Ceremony that you had partially given up after your battle with cancer?

- At that time, it still wasn’t decided that the 2020 Olympics/Paralympics would come to Tokyo in 2020, but when I watched the opening ceremony for the Paralympics at London in 2012, for the first time after becoming disabled myself, I was very much impressed with the ceremony that Jenny Sealey directed, and it influenced me a lot, and it made me feel that I wanted to do performance and I wanted to do art. At that time, it had been two years since my battle with cancer and I was beginning to see the possibility of planning work a little farther into the future, so I announced that I wanted to do the [2020] Paralympics Opening Ceremony.

- For the performing arts-related program of the Yokohama Paratriennale 2014 you had workshops by Catherine Magis of Belgium who is known for her work with intellectually challenged people and the creative workshop the Espace Catastrophe, and by Pedro Machado Artistic Co-director of the Candoco Dance Company known for both disabled and non-disabled dance.

- Having watched Jenny [Sealey’s] opening ceremony, I decided I wanted to begin with the non-verbal performing arts of circus and dance. And when I started actually working on these projects I found a number of issues involved. We held workshops by the circus artist Keisuke Kanai, who joined our project in 2014, but despite publicizing them actively, we found that there were very few applications from people with disabilities who wanted to participate. We arrived at the conclusion that there was a problem of accessibility.

Our aim had been to try to reach a high level of artistic expression in the project, but we realized that we couldn’t even get to the starting line if there weren’t more people who actually wanted to do expressive performance. That led us to start the Slow Movement program. Partly because of a strong feeling that we didn’t want the seeds we had planted with the 2014 Paratriennale to die, we made this a program that would create opportunities in which people who liked to do movement and to express themselves in front of others could easily participate in a variety ways and a variety of easily accessible places. Also, Slow Movement serves as a platform for nurturing performers and staff and developing their skills. Now we are even expanding it to aerial performance. - In addition to starting the Slow Movement program, you have also begun training for access coordinators and accompanists to support performance by people with disabilities.

- For people with disabilities, even if they want to participate there are the physical handicaps that will often prevent them from getting to the activity venues, and then there are the problems of scheduling with their families of facility staff, all of which create very high hurdles for them to overcome. In the case of people who rely on wheelchairs as well, there are quite different levels of capability between individuals. Some can get on and off their wheelchair without assistance while others can’t. Because the degrees of disability of each individual has to be grasped and the assistance given must be carefully customized and followed through on in accordance with each of their needs, it is a degree of burden that normal facility staff cannot be expected to take on; and the results can lead to accidents. That is why we decided to rely on trained access coordinators.

One of these coordinators was a fellow college theater company member and friend of mine who worked as an actress while studying nursing. She had retired from acting and was working at a normal job for a lining, but she had a nursing license and a knowledge of theater, so I thought she would be perfect for the job. Even though there was no precedence for the job of access coordinator and we didn’t know the best ways to operate, I asked her to come and work with us. There was an incident that led to my asking for her help that arose when I invited Kazuyo Morita (an artificial-leg actress and dancer suffering from congenital scoliosis and spina bifida) to come from Osaka to perform at the 2014 Paratriennale to perform. I was told that she would need a couple of medical treatments during her stay in Yokohama and thought that I could arrange for it from a nearby hospital, but I was told that the hospital could do an inspection, but they couldn’t give [out-patient] treatment. I realized that we had to arrange a visit from a caregiver and that we needed to have a system to enable it.

In order to expand our activities, getting trained staff is a critical need, and we are currently seeking access coordinators and we have started an “accessibility seminar” to train access staff from the general public. - When it comes to the performance, it is the accompanists that are important, aren’t they?

- When we started the Paratriennale in 2014, accompanists was already one of the key words. The performers themselves were of course important, but I felt also what an important presence the people like facility staff and family members who kept close by to assist in their creative work were. From our monozukuri and art workshops I got a real sense of how the creativity of these accompanists and the level of sensitivity they brought to the work had a very big influence on the quality of the output. However, very little attention was ever focused on them, most of it was focused on the issues of the [disabled] who were the main players. So, rather than having that type of situation continue, one of the concepts of the Paratriennale was creating an environment where it would be possible to raise the level of creativity of the accompanists who were supporting the disabled participants. In order to carry on that spirit, we started using the word “accompanist” (in the sense of an accompanying performer) for these people who assisted on stage to bring out the full potential of the disabled performers.

- They have accompanying runners for the Paralympic torch relay, so it is like the artistic equivalent of them, isn’t it?

- Yes. Some might as if it is really necessary seek the assistance of people with a name like accompanist, but we do it because these are not just works that we are creating for our own enjoyment. It’s because we want to create things that we can show with pride to a certain level of audience. And to achieve that level, I believed it was necessary to have such people as intermediates between the director and the performers such as people with mental disability.

- By the way, are the accompanists people with dance experience?

- It turns out that it is best if are. In the early stages, I tended to think of all the assistants without disabilities as accompanists, but as we progressed it turned out that wasn’t necessarily true; we realized that their simply being dancers wasn’t enough. They needed to have something extra, like an ability to see what was happening around them or an ability to offer care. But, if you made that the main criterion, there was a danger of it just becoming a show of care-giving and fall short of becoming a creation. It is actually quite a technically difficult skill to be able to give support in the midst of a creation. Once the performance begins, there is nothing that the director can do, so the accompanists on the stage are extremely important.

- I have seen a number of your works performed and what really surprised me was the way the accompanists and the disabled performers seemed to move as one so naturally.

- If the performer and the accompanist appear to be a one-on-one pair, it will be clear that one is caring for the other. So, to avoid that impression, we will have different accompanists in position to provide care/assistance for a certain movements, so that as the scenes progress we change the pairings in what is in fact a very complex orchestration to avoid the one-on-one, performer-accompanist impression from developing.

- What is your own role in these performances?

- It is as general director. I am in a position where I supervise the overall production; I don’t do anything specific like choreography but leave those responses to the individual directors. I create a team including the access coordinators, accompanists and also the production staff, and then I get someone like a guest choreographer to join us.

- The Paratriennale that you launched in 2014 is to be held three times in all, with the second in 2017 and the final one in 2020. What kind of program to you have planned for this year (core period from Oct. 7 to 9)?

- This year it is going to be held on a grand scale! We are going to use the entire Zou-no-Hana Park and make a “Wonder Forest” in it. The collaborative work on this has already begun with people from the general public working together with our artists. Scattered around in the forest a various works of art that are intended to stimulate the five senses in ways that change our normal perceptions of the spaces around us. The Wonder Forest guides will be “Rabbits,” and we 70 applications from people wanting to audition for the Rabbit roles. We are making a specially designed large circular stage in the form like a grand roundtable that people gather at to share a communal meal and the plan is to also have 30-minute contemporary circus performances. Of course the performers will be a mix of people with disabilities and without, and totaling about 120 performers in all.

- At [the end of] the Rio Paralympics, you served as stage advisor for the Paralympic Flag Hand-over Ceremony (from the Rio Mayor to the Governor of Tokyo).

- For that Rio ceremony, it was the same team representing both the Olympics and Paralympics contingents for Tokyo, but few people on the team had experience working with the disabled, so they came to interview me because I had organized the Paratriennale, and eventually they had me attend their directorial meetings. I ended up giving advice about what would be necessary to stage the things that Ringo Sheena (Creative Supervisor / Music Director) and MIKIKO-san (General Director / Dance Choreography) wanted to do; suggesting people I knew who could be of help in certain areas and giving advice about on-stage dynamics/logistics, etc.

One of the biggest hurdles we had to clear were the problems of getting all the people and equipment to Rio. Getting people with disabilities to make long trips is more difficult than most people could imagine. The flight time to Rio from Tokyo is 36 hours, so we talked in great detail about how to chose people who could stand that kind of trip, how to get them to Rio in good condition, how many rehearsals we should have there and how to make it possible for them to perform with no physical or health problems. We interviewed the performers with disabilities such a wheelchair dependency in order to hear their detailed requests about what kind of room they needed at the hotel in Rio, and if that wasn’t available to have a certain type of shower seat available, etc., and then communicate those requests to the staff. - In other words you were effectively doing the work of an access coordinator, weren’t you. What kind of system did you end up creating?

- We had about nineteen performers, of whom about nine had disabilities. From Slow Label we brought four access coordinators and four accompanists. Since the four access coordinators alone could not handle all of the room and meal care for the disabled members we also requested the services of professional care-givers. There was a lot of work involved and some problems we encountered, but everyone worked together cooperatively, including mutual help between the disabled people where possible, and I feel that in the end we achieved a virtually ideal environment for everyone.

- After Rio, I believe that the next big step for you was moving to your new base of activities at the Shin-Toyosu Brillia Running Stadium (*4) that opened in December of 2016.

- Spiral had submitted to launch a “Toyosu Conference” to discuss community development for the Toyosu area where the Tokyo Olympic/Paralympic Athlete Village will be constructed and from talks with prominent young figures, the concept of “Sport × Art” (Sport by Art) emerged as a theme for activities. The facility was established as a base for these activities, and since we wanted a place where we could conduct aerial performance training, we made requests to that effect. This it the facility where that dream was finally realized.

- What kinds of things are you doing at the new facility?

- Starting from the Paratriennale of 2014 and our subsequent Slow Movement program, the performers have made great progress. At first we had artists like Kanai-san and others come in to hold workshops for them to heighten their expressive/artistic skills, but now they have reached the point where they can attempt performing things like aerial acrobatics. In the process, we have seen how people who could only raise their arms to a certain degree at first became able to raise them higher and thus increase their range of expressive capability. And people who couldn’t keep count with the beat at first gradually became able to and thus became able to dance. In these ways we have to raise the performance skills of all of the performers. And in order to do that, we have started to use physiotherapy and occupational therapy methods and brought in personal trainers who know how to work with the disabled performers’ bodies. This brings more life to the circus performance we have been doing with Kanai-san, and it has brought us closer to the Sport x Art concept as well.

When you observe what is going on in Europe, you find that things like “social circus” programs have become commonplace and there are physical therapists and such and they are helping to people with disabilities or the elderly who normally don’t have opportunities to exercise attend programs that help strengthen their health and physical capabilities. Unlike rehabilitation-type programs to help people start walking again, if it is a program aimed at circus type expression or an art program, it can give the people new motivation, like the desire to try juggling or to try aerial acrobatics or to begin dancing. And once people get this motivation, you find that their functions start improving, and this has brought increasing attention from the medical community.

Until now, the main focus of medical treatment has been rest and repose, and this has led to secondary disabilities such as obesity, for which prevention has become an important issue. In fact, when I was in the hospital getting treatment in the rehabilitation section of the Orthopedics department, when I explained about our circus program to the doctors there, the response was one of real interest, so I want to work with specialists and organizations in this field to develop a program that can bring change to Japan’s medical practices and the environment for people with disabilities. If we can do this, I think it could be a truly meaningful legacy of the Tokyo Olympics/Paralympics. - From the perspective of art, there is an aesthetic which says, for example, rather than trying too hard to raise the arm, it is often more beautiful to raise it to a natural height, without pushing too hard. What do you think about that ideal?

- Ideally, there is nothing better than being to raise it simply and naturally. But, if there is no opportunity and no place for people who want to take on the challenge of trying to raise it, we want to give it to them. Whether it is in sports or whether it is in arts, people without disabilities can take on the challenge of running a marathon or learning ballet if they want to, as a hobby. But, I have always felt that for people with disabilities, the possibilities they see in front of them are much fewer; they can go all out and become a Paralympian or they can do nothing, and there are very few choices in between the two. Our aim is to give them at least one alternative choice. Also, the people who have acquired the skills to support people with disabilities (access coordinators/accompanists) through our programs later return to their hometowns or move on to other regions, perhaps they can help a ballet studio there open itself to also receiving people with disabilities, can’t they? We hope to nurture a lot of who can serve as “agents” in that way and have them spread around the country. I believe that is the job we should be doing until 2020 [the Olympic year].

- In the past, your dream was to direct the Opening Ceremony for the 2020 Olympics. In reality, what is it that you want to do now?

- Now, we have three projects that we are planning for 2020. One is the opening and closing ceremonies, another is the Yokohama Paratriennale, and the third is an arts festival for people with disabilities that will be jointly organized by the Nippon Foundation and UNESCO. I am now working as program advisor for that arts festival, and what I want to do now is to train people to support disabled people for these events. In order to get other organizations involved in these activities, I am now working on building lateral relationships.

It is not a case where I want to take on the role of artistic director or stage director, I just want good use to be made of the know-how we have accumulated and nurtured until now. And one more thing is that I want to see that people with disabilities are included as they should be in both the cast and the staff for Olympic/Paralympic ceremonies. Of course that will make things more difficult in some ways, but I don’t want to see their inclusion be avoided for that reason. If the easier path is chosen, nothing new will be gained. If the challenge is taken on without flinching from the difficulties it presents, things should be different and new gains made from 2021 onward. So, that is what I want to continue asking people to do. - In the past, you have said that after 2020 you would like to see a world where the word disabled isn’t used anymore. As our last question I would like to ask you about the better world that you envision for the future.

- In a word it is complementarity in the relationships between all people—everyone has their own place and those relationships are complementary. It doesn’t matter whether a person has a disability or not, there are things that I (we each) can do and things that I (we each) can’t do, we all have our own unique qualities. People who can do some particular thing can help others who can’t, and there may be other situations where the positions are reversed and the person who couldn’t do that task will be able to help the person who could in another task where they are the one who needs help.

What makes this kind of complementary relationship between people possible is imagination and creativity. When we see someone who is facing a problem, it is imagination that we can use to think of how to be of help to them, and then it is creativity that we use to find a way to do it. If all kinds of people with different abilities bring together their powers of imagination and creativity, all of us, whether we have disabilities or not, should be able to find a place where we can contribute to society and coexist as a whole. That is my image of the ideal society, and I believe that the performing arts offer the means to nurture those two vital elements of imagination and creativity.

Yoshie Kris

Yoshie Kris (SLOW LABEL)

Working toward a society without the word disabled

Yoshie Kris

Born in Tokyo in 1977. From the age of seven, Kris began taking classes in creative dance. As a high school student she was inspired by the Lillehammer Winter Olympics Opening Ceremony and decided to enter the Tokyo Zokei University of art and design. From 2006 to 2007 she studied at the Domus Academy in Italy and received a Master’s Degree in Business Design. In 2010, Kris was diagnosed with malignant fibrous histiocytoma and due to this ailment completely lost lower limb function in her right leg. In 2011, she established and served as director of Slow Label, an enterprise to create products through collaborative work between people with disabilities and artists from Japan and abroad. Since then, she has worked consistently through programs such as establishing the Yokohama Paratriennale 2014 and programs that bring together people with disabilities, artists and people from the general public with the goal of building social platforms that help people live creative lives regardless of whether they are disabled or not. Kris is the winner of the “Contribution to the Arts and Culture Award” of the 65th Yokohama Culture Awards and the “Face of Tokyo” award of the Time-out Tokyo LOVE TOKYO AWARDS 2016.

Interviewer: Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto, Director of the Center for Arts and Culture, NLI Research Institute

SLOW LABEL

https://www.slowlabel.info

*1 STOMP

is the world-famous Brighton-based British percussion group. The group uses common non-instrument tools in acrobatic rhythm performance.

*2 The creation of Slow Label

At the Spiral/Wacoal Holdings Corp. Art Center a “Rendez-vous Project” was being promoted as a platform for a new type of monozukuri (product creation) based on new perspectives resulting from “rendez-vous” (encounters) between artists and corporations. In 2009, the consignment for the management of the Zou-no-Hana Terrace led to the birth of an experimental business project named “Yokohama Rendez-vous Project” designed to bring artists active in Japan and abroad to welfare facilities in Yokohama and have them cooperate on new product creation (monozukuri). In 2011, Yoshie Kris was appointed director and established the variety brand Slow Label for solely handmade one-of-a-kind products. The following year, saw the start of the Slow Factory as a general public participation program where anyone could gather and interact with others through the process of product creation, regardless of whether they had disabilities or not. With the subsequent establishment of Slow Label Tokushima, Slow Label Kumamoto and other programs the movement spread nationwide. In 2014, the international contemporary art exhibition “Yokohama Paratriennale 2014” was organized to present works resulting from collaborations between people with disabilities and professionals from a variety of areas. Taking this opportunity, the NPO organization Slow Label was established. Now Slow Label is involved in a variety of programs, like the Slow Academy study program for thinking about ways for people from various walks of life to meet and collaborate, and the Slow Movement platform aimed at nurturing human resources specializing in the discovery, nurturing and support of performers with disabilities, and other programs that use the power of the arts to create opportunities for people to come together, meet and collaborate on projects.

https://www.slowlabel.info

*3 Yokohama Paratriennale 2014

Dates: Aug. 1 to Nov. 3, 2014 (Core period Aug. 1 to Sept. 7)

Venue: Zou-no-Hana Terrace

Theme: “First Contact – The place of first encounter”

An exhibition for works created in collaboration between people with disabilities and artists and performances of works created in workshops with people with disabilities.

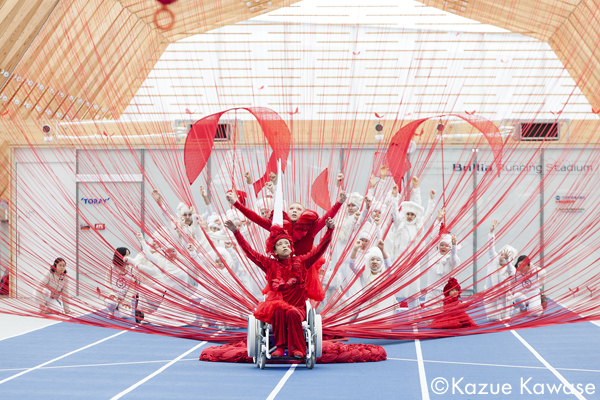

*4 Shin-Toyosu Brillia Running Stadium

The Running Stadium is an all-weather type temporary facility with a 60-meter track and facilities to assist para-athletes, such a laboratory for the development of artificial limbs. (Dimensions: 108 meters in length, 8.5 meters at the highest point and width of 16.7 meters. Its arched roof is covered in ETFE film.) Designed by Yukiharu Takematsu and E.P.A.

SLOW MOVEMENT -The Eternal Symphony 2nd mov.-

(Feb. 11, 2017 at Shin-Toyosu Brillia Running Stadium)

Photo: Kazue Kawase

SLOW MOVEMENT -Next Stage Showcase & Forum-

(Feb. 12, 2017 at Spiral Hall)

Photo: Kazue Kawase

Related Tags