- I would like to begin by asking you about your personal background and what you were doing before you became a producer in the arts.

-

I was born on the outskirts of Brussels. In fact, that is where I still live. I studied acting and directing at three of the main theater schools in the Flanders region, Studio Teirlinck in Antwerp, the Conservatory of Ghent and RITS in Brussels. The education at that time was generally more traditional than today, and varied with each school, but basically I learned about the work of the Theatre of the Absurd playwrights, and the experimental work of Peter Brook and Jerzy Grotowski.

The latter half of the 1960s into the ’70s was a period when politically oriented theater was a great phenomenon throughout most of Europe, and political theater was the newest kind of theater at the time. One very important work of that time for Flemish theater, for European theater and for me personally was the production of Dario Fo’s Mistero Buffo mounted at the Avignon Festival under the direction of Arturo Corso and Wannes Van De Velde in 1973. After that I did some work as an actor and director but I was already becoming fascinated in the work of organizing and producing. When I organized the first Kaaitheater festival in 1977, I was still just 23. - What made you decide to establish the Kaaitheater in Brussels?

- Personally, I was very much influenced by two important institutions in Europe at that time. The first was the Mickery theatre in Amsterdam. That was a theatre that invited avant-garde American theatre artists like Robert Wilson, Bread and Puppet and the Wooster Group. The second was the Nancy Festival founded and directed by Jack Lang. The Nancy Festival was the most important theatre festival at the time and it brought us avant-garde theater, in particular student theater from the communist block countries and theater from America. The Nancy Festival is also the first place where I saw Tadeusz Kantor and Pina Bausch.

- Now that I think of it, those were the first two institutions to invite Shuji Terayama from Japan. Also, the Nancy Festival was instrumental in introducing Butoh in Europe as well.

- I wanted to create a place in Brussels where we could present works like that. When the opportunity arose to establish a festival, I was able to invite three of the works I had seen at the Nancy Festival in April of 1977 to perform in Brussels in September of that year. That became the beginning of the Kaaitheater. It started as a biennial festival. During that era we invited many works of the political theater and avant-garde theater that were so stimulating at the time from Spain and Germany and Belgium to our festival.

- That was also around the time when De Schaamt (meaning “shame”) was established, isn’t it? I have heard that it was a very important management organization in which Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and Jan Lauwers also participated. Can you tell us what kind of organization De Schaamt was?

-

You could probably call it a production organization that was started among friends. It was unlike any other organization existing at the time, bringing together a group of young artists who wanted to do things that weren’t allowed anywhere else. It wasn’t a group that was open to anyone, because there were very high standards set for taking in new members, but thanks to that it was a group that had a great sense of trust between the members and magnanimous openheartedness. You could say that it was like a group where everyone shared the same bank account. The income that one artist earned would be used to finance another artist’s new creation. Of course it wasn’t all operated on the basis of rough estimates. At the end of each year we had the accounting done to report what each company had earned.

The central figures in De Schaamt were a unique 3-person unit named Radeis. Today we would call what they were doing “visual theater,” but at the time there was no better name than to call it mime. The central artist in the group was Josse De Pauw, who is also the partner of Rosas’ Fumiyo Ikeda.

The latter half of the 1970s saw the beginning of a number of festivals of fool that began in Amsterdam in 1975 and spread to Germany, France and other countries of Europe, leading to what might be called a festival of fool generation. Looking back, you might say that was a time when we had a chaotic jungle of the movements that would later separate into avant-garde theatre, dance, circus and street performance. And, because the progressive festivals would invite Radeis to perform, I made many acquaintances among producers throughout Europe.

After that, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, and later Jan Lauwers, also became involved in De Schaamt. Thanks to their successes, I was able to work as a producer promoting both well-known and emerging artists. In 1985, De Schaamt merged with Kaaitheater to become one organization. Guy Cassiers is one of the most active directors not only in Flanders but in Europe as a whole, and he was another who began working at Kaaitheater.

Besides presenting performances, Kaaitheater was also involved in producing works and we were very fortunate that during the latter half of the 1970s into the ’80s there were arts centers throughout Europe that invited us to perform our works. In Flanders, independent arts centers such as the Stuk in Leuven, the Vooruit and the Nieuwpoort in Ghent, the Monty in Antwerp and the Limelight in Kortrijk were established. The Kampnagel in Hamburg was particularly well known, but this trend was occurring not only in Germany but in the Netherlands and Switzerland as well.

Since most of the companies were operating then without any public funding, there was virtually no pay for the performers, but performing at these arts centers was meaningful as a platform to bring their works to a larger audience. Many of the artists had to depend on unemployment insurance to continue performing, and I myself also did for some time.

Then I began to feel the need for a year-round format that didn’t end after a short run. We began having Kaaitheater present works year-round, but for the first five or six years we didn’t have a theatre facility of our own, so we had to rent a number of different theatres. We were like nomads, constantly moving from place to place to offer performances. In 1983 we bought a building that had been a beer brewery and is now the Kaaitheater Studio. It became our base and our studio space for working on productions until the early 1990s. We became acutely aware of the need to have our own theatre, and when we found the Lunatheater, which had been built in the 1920s and then used as a warehouse, we convinced the Flemish government to purchase it. - Earlier you mentioned receiving unemployment insurance. I have heard that Belgium has the same kind of “intermittent” (*) system that France has, to support performing artists when they aren’t performing. Is that what you were referring to?

-

At the time we didn’t have any system like the intermittent. However, there was a special arrangement made for people working in the arts and culture or social work that exempted them from the usual requirement of going to the city office every day to get a stamp of certification that you are still unemployed. So we were able to receive unemployment insurance without having to go to the city office every day like other unemployed workers. Later a system that is similar in parts to the French intermittent was introduced and today there are many artists receiving income from this public source.

* This is a system under the employment insurance framework by which performing artists and technicians that have worked for a certain amount of time in the profession and are employed on an irregular basis are recognized as salaried worker and receive unemployment insurance during periods when they are not under contract to work. - Currently, people like Alain Platel (Les Ballets C. de la B), Jan Fabre (Troubleyn) and Jan Lauwers (Need Company) have their own companies that receive funding and use part of it to support the creative activities of young artists and promote them, don’t they? This kind of use of grants seems to be a characteristic of the Flemish theatre world.

- I think it is safe to say that it was our generation that started this kind of solidarity. In the days of De Schaamt we were not receiving government grants, so the conditions were different and we couldn’t expect to get grants (unlike today when theFlemish government is very generous in giving grants to the arts). So artists learned to help each other through a flexible sharing of funds that served the same function as grants today. Perhaps in the area of unemployment insurance as well (laughs). In Flanders there is relatively little competition and conflict between the generations concerning the distribution of grants, and I think that is a good thing.

- It appears that the various arts centres were created from independent movements but they maintained a kind of solidarity as a group. Is that true?

-

As you know, Belgium is a small country, so we all knew each other and joined together to establish a network. We created the Flemish Theater Circuit (VTC: Vlaams Theater Circuit) as confederated organization of arts centres in Flanders. As a confederation, VTC made it easier to invite foreign artists and organize performance tours for them, and it also served as a platform for talks with the government about cultural policies. This became the parent organization for Flemish Theater Institute (VTI, Vlaams Theater Insituut). VTC is an organization that I led the founding in the late 1970s. In Flanders at the time, there also were cultural centres, separate from the arts centres, made up mainly of facilities in smaller cities like Hasselt and Turnhout, and among these culture centres were some engaged in international activities, so we cooperated with them too.

With this group of colleagues we worked out the methods for coproductions that are now common. Because at that time we didn’t have enough funding. Although Kaaitheater gradually became recognized in the 1980s and began receiving grants from the government, the amounts were still quite small, nothing compared to what it is receiving now. And there was almost no funding support for the artists.

The first case of such a coproduction was Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s first major work, Fase (1982). I knew her personally, I saw her prior work, Asch , and had gone all the way to New York where she was studying at the time in order to follow her works’ development. . At the time it was something rare, but there was a studio video of her Violin Fase , and I showed it to some presenters, saying, “Flanders has a new emerging talent.” But their reactions were quite negative. They couldn’t see any reason for investing money to help create such strange work. But, I worked hard and convinced them to agree to finance together this production, and now they boast that they were the first ones to work with Keersmaeker (laughs).

After that, as the conditions changed and the needs shifted so that, rather than continuing to be a mother organization for making coproductions and inviting foreign works, it became more important for us to concentrate on building a firmer foundation from a cultural policy standpoint and support networking. So, VTC changed its mission and became VTI in 1987. Guido Minne is the man who started the Stuk in Leuven and joined the staff of Kaaitheater in 1979. He became the first director of VTI and built the foundation of the VTI as it stands today. - That is why VTI has its office in the Kaaitheater building along with IETM, isn’t it. I hear that you also played a central role in the founding of IETM. Would you tell us how that came about?

-

IETM is an organization born around 1981 as a natural product of the times. It was a time when arts centers were being established and active not only in Flanders but in Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands and throughout Europe. We had gotten to know each other through the artist tours we were involved in, but we had the feeling that we wanted to meet more often and talk at greater length about the artists we knew well. That is what led us to form a group that met regularly. This was the beginning of IETM as a platform for informal meetings of theatre people

(*)

. IETM offered opportunities for theater professionals to transcend national boundaries and language barriers to meet, get to know each other, and perhaps have a drink and some good times together. It made it possible for us to work together on a friendly basis. I believe IETM created a culture where coproductions and collaborations became commonplace.

* IETM was the acronym for Informal European Theatre Meeting, but now it calls itself the International Network for Contemporary Performing Arts. - Belgian cities have been chosen as European Capital of Culture three times: Antwerp in 1993, Brussels in 2000 (the special millennium year in which 10 cities were selected) and Bruges in 2002. Of these you were the person responsible for the organization twice, for Brussels and Bruges.

- The European Capital of Culture program was started in 1986, and each year numerous friends and colleagues of mine were involved. So, I was familiar with the work involved in organizing a city’s program even before I was chosen to do it myself. When Brussels was selected in 2000, I accepted the position of artistic director, but it turned out to be a painful experience. Because of the political confrontations between the French-speaking factions and Dutch-speaking factions, I had to resign my position after just four months. For the Bruges Capital of Culture year in 2002 I served as general manager, and this time things went very well. That program is still referred to often internationally as an example of a successful program.

- You have always been deeply involved in arts festivals, but from your experience of starting Kaaitheater as a festival and eventually turning it into a permanent theatre and serving as its director, you know both festival and theatre operation intimately. What do you think should be the role and meaning of a festival?

-

To make the story of Kaaitheater simple, we found that in order to do justice to the job of inviting foreign works and presenting our coproductions and the works of the De Schaamt artists, we needed more than a short-run festival. We needed a year-round program. And that is why we turned the Kaaitheater festival into a theatre operating year-round.

Concerning the role of festivals, there are so many festivals today with so much diversity in terms of their contents that it is very difficult to make general statements about what a festival should be. Of course, you can probably say that the general character of a festival is that it can concentrate a lot of energy, intensity, enjoyment and diversity in a short period of time, and it can function as a platform for encounters and discoveries and it can achieve the stimulating atmosphere close to that of a feast or a party. Here at TPAM in Yokohama, as well (this interview was conducted at BankArt NYK during TPAM) you have many lectures, debates, workshops, showcases, booths presentations are concentrated in a one-week period with a festive atmosphere, which, for the theatre professionals in particular, creates a very intense and productive week. This can serve as a very powerful driving force for getting people to encounter and appreciate new or previously unknown things.

In the festival context it is easier to show foreign works, the works of younger artists and unconventional experimental works and it is possible to get a bigger response to these works than would occur in a normal theatre context. It is the same as the case of an art exhibition: the reception it will get at a single commercial gallery in some city is nothing compared to the reception the same exhibition would get at Documenta or the Shanghai Biennale, for example. There is more freedom at a festival than what you have at a theatre. It is because the audience itself comes to a festival with the expectation of being surprised. That is the strong point of a festival. There are some festivals that are held with the aim of raising the city’s cultural image or bringing in an economic effect, and that is fine. But, the festivals I am concerned with and interested in are the ambitious ones that try to create a context and an environment that make it possible first of all for the artists to create and present outstanding work. - In recent years you have been working at the offices of the European Festival Association. Would you tell us what kind of organization the EFA is?

-

EFA is an organization founded in 1952, primarily under the initiative of the Swiss intellectual Denis de Rougemont, mainly with music festivals like the Bayreuth and Aix en Provence festivals that are still famous today. De Rougemont was one who sought to encourage atonement and understanding among the nations of Europe through the arts and culture, and in that sense he played an important role in the unification of Europe after World War II. EFA was initially an organization that held its general meeting and congress once a year for the festival directors to meet in order to strengthen relationships and exchange information. Initially its mission didn’t include promoting coproductions or lobbying for cultural policy changes. In the classical music world, much of the process of employing orchestras, singers and musicians is taken care of by agents, so it was meaningful to have a platform for exchange of information in that area. Since classical music festivals also existed in the old Eastern Europe, EFA later sought to get the festivals of the communist block to join its membership, and in that and other ways it was able to serve as a bridge for cultural exchange between divided Eastern and Western Europe.

This makes me recall that since 1961 there was a contemporary music festival in the Croatian capital of Zagreb. The current President of Croatia, Ivo Josipovi?, was the director of that festival, so I know him well.

EFA underwent a major revisions when its president was a person who also served as director of the Holland Festival, Frans De Ruyter. It began taking in as new members not only music festivals but also theatre and dance festivals. This resulted in a more diverse membership. The Holland Festival is large in scale and important in the fact that it included not only music but avant-garde theatre and dance in its program. Due in part to the inconveniences resulting from the fact that Switzerland is not a member of the EU, the head office of EFA was moved from Geneva to Ghent. Now the EFA office is located in the Flanders Festival office in Ghent. Later I was given the job of Secretary General of EFA. Now my former assistant, Darko Briek has taken over the job and is working to carry on and develop the functions of EFA. - What sorts of activities is the EFA involved in now?

-

There are four main programs: research, publication, human resources development and cultural policy advocacy. Although it isn’t really sufficient yet, we are proceeding with research concerning festivals in association with a group of researchers. In our publication activities we are publishing our EFA Books series, including reports of our research results.

We have also begun a training program for young festival managers named the Atelier for Young Festival Managers. This program gathers young producers twice a year to hear lectures by leaders in the festival world and participate in roundtable discussions aimed at sharing the lessons learned from the history of festival activities and discuss ways to improve the creative environment for artists. EFA is also involved in initiative aimed at formulating cultural policy on the pan-European level. Preparations for this began in 2008 and we officially launched the European House for Culture in 2009.

This European House for Culture develops partnerships with cultural network organizations operating in Europe or in the international context and engages in administrative work and providing platforms for meetings and exchange. The European House for Culture has office space in a corner of the Flagey arts centre of Brussels, and partner organizations can also use office space there. By all sharing the same coffee maker we create more opportunities for encounters and networking. Another aim of the European House for Culture is to reflect the voices of the arts centres in establishing arts and culture policy on the European level. - I feel that all you have told us today about the experiences and successes you have had in Flanders since the 1970s will surely prove valuable, as we think about our performing arts environment here in Japan. Thank you very much.

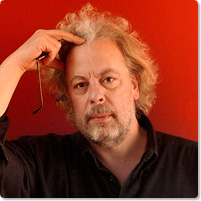

Hugo De Greef

Hugo De Greef,

presenter behind the “Flemish wave”

Hugo De Greef

Since founding the Kaaitheater in Brussels in 1977, Hugo De Greef has been instrumental as its director in bringing into the world performing artists of the Flemish region of Belgium, such as Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and Jan Lauwers, a movement called “Flemish Wave”. Through involvement as a producer in the Festival of Flanders and participation in co-founding the establishing of IETM (International Network for Contemporary Performing Arts), he has worked to build networks to support theater people, theaters and festivals.

(Interview: Shintaro Fujii)

Kaaitheater

https://www.kaaitheater.be/

Related Tags