- It’s been a quarter of a century since NPN’s inception. Please tell us about how it began.

- The National Performance Network (NPN) was founded in 1984 as a project of Dance Theater Workshop (DTW) (*1) in New York City. David White, then the artistic producing director at DTW, saw that there were a lot of artists working in isolation all over the United States, and that it was very hard for many artists to leverage their work outside the local arena. It was very difficult for artists in smaller cities, or even large cities like Chicago, for example, to get their work visible nationally. So, the idea of creating a network of organizations that present touring artists is the structure that he imagined to help breakdown that isolation. Isolation had to do not only with geography but artists working in communities of color. For instance, African, Asian, and Native American and Latin American artists were working in communities that were often isolated from the larger community, even in their own city, and there were exciting contemporary works happening in those communities as well. It was about leveraging new opportunities for the artists.

David raised some funds from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Ford Foundation, the initial funders of NPN. The fund was used to convene a meeting. He brought together 14 organizations at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota and proposed the idea of what NPN can be and how he imagined it could be structured. The idea was to create a network of organizations with a national office that would raise money and provide subsidy resources for touring artists in this context. I happened to be among that group. At that time, I was a co-director and one of the founders at the Contemporary Arts Center in New Orleans. We were a perfect candidate for an NPN member, as the Center was presenting touring artists and was artists-centric and artist focused. We were extremely interested in providing opportunities for local, New Orleans-based artists to get their work out nationally as well. How we described it (the NPN idea) was ”Manna from Heaven!”

The NEA and Ford Foundation gave two years of funding, and those 14 organizations grew to 19 after the pilot (the meeting and the creation of the structure). At the initial meeting in Minneapolis, we looked around the table and said that there are a couple of organizations missing who should be at the table. There were no organization of color, for example. At that time and to date, we are very committed to have an inclusive network that represents the diversity of the U.S. When the 2-year launch happened there were 19 organizations and several of them were organizations of color, so, we started to diversify right away.

Although the DTW’s primary mission was dance, they were presenting some music, particularly new music, and some performance art. Thus, NPN was multi-disciplinary in the performing arts from the beginning. (The visual arts came much later.) In this way, NPN’s programs, based on the concept of “Tour Residencies” and “Fee Structure” started to function and develop.

*1 In December 2010, DTW merged with Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company and became New York Live Arts. - Please elaborate on the two concepts that are the premise of NPN programs.

- The idea of artists’ “residency” (*2) has become a trend in the field nowadays, but before NPN’s programs, the prevailing touring model was that an artist group arrives in the city, they load-in to the theatre, tech, rehearse and perform the show, then load out and leave. It was an exhausting way to live on the artists’ side, to spend 2.5 days in a new city without any context, without really knowing where you are and totally dependent on the presenter for the audience. On the audience and presenter side, that touring model had not enough opportunity to contextualize the work for the audience. So, the presenters were less willing to take risks on experimental works or emerging artists. In order to improve this situation, NPN created a structure for touring artists to stay in one city a minimum of one week and included the requirement for some community engagement beyond the work on the stage. In other words it merged the residency idea with artist tours. This is the “Tour Residency” (*3)

- The other issue was that since artists were so eager to take limited touring opportunities when such came their way, they often lost money by touring. Therefore, the idea of a “Fee Structure” was important. It is a structure that defines compensation for the artists’ work and conditions for such items as lodging and per diems regarding tours. With the money taken off the table, the artist and presenter can sit as equals to focus on discussing how to bring the work to the audience, and thus their mutual goal of audience development.

*2 “Residency “is one of the words that came to encompass wide range of meaning in the art word. It may mean that the artists go away and be secluded in a studio privately. NPN’s “residency”, means living in and being a part of the community for at least a week.

*3 Official name of the NPN programs are “Performance Residency” and “Visual Arts (VAN) Residency” for visual arts. - The other issue was that since artists were so eager to take limited touring opportunities when such came their way, they often lost money by touring. Therefore, the idea of a “Fee Structure” was important. It is a structure that defines compensation for the artists’ work and conditions for such items as lodging and per diems regarding tours. With the money taken off the table, the artist and presenter can sit as equals to focus on discussing how to bring the work to the audience, and thus their mutual goal of audience development.

- Twelve years after the inception, there was a big transition for NPN.

- In 1997, DTW was faced with a capital campaign to build a new performance space. By that time, NPN had grown to be a network of 55 partner members. It became apparent that it was not possible for NPN to continue to be a part of a parent organization while it was trying to fundraise for its own programs, infrastructure and the capital campaign. Thus, in 1997, we spun off from DTW and became an independent 501(c) (3) [nonprofit organization].

- What was your relationship with NPN at that time and your role in this major transition?

- I was the managing director of Junebug Productions in New Orleans at that time, but I was also a co-chair of the Advisory Committee, which became the independent NPN Board. Thus I became a co-chair of the Board of NPN. Loris Bradley was my co-chair. We hired San-San Wong as the first executive director when we became the independent organization. We owe her an enormous debt of gratitude for setting up our infrastructure. She did all the hard work and stayed as the ED for about 18 months before resigning. Putting up all the infrastructure for the new organization also meant fundraising for it. It was a momentous time. We were not sure if NPN could survive because we had to build on the infrastructure and simultaneously keep our programs going. It was the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation that supported us during this transition with their “Bridge Grant.” Then, Loris resigned from the Board due to a transition in her own life, so I became the NPN Board Chair.

After San-San resigned, the Board made a decision that before we hire another ED, we would do a National Planning Process to see if there was viability for the NPN to survive. We spent about eight months doing a series of roundtables around the country and using the “Bridge Grant.” The roundtables were really focus groups and they included the current NPN members, in the cities where they were or they could travel, plus other presenters and artists who were locally based where we held the meetings. The affirmation of the value of NPN from the field was tremendously positive and very reinforcing. At the same time, we were meeting with funders – both the current funders as well as potential funders whom we hoped would support us in the future. So, we did that cultivation of relationships for fundraising and we received strong affirmation as well. We were also invited to submit a renewal proposal to the Duke Foundation, which resulted in a three-year grant from them. At the end of the National Planning Process, I was fully convinced about how much NPN was needed in the field. So, when I was offered the position President and CEO by the Board in 2000, I decided to accept it. - Why did you move the NPN headquarters to New Orleans?

- It was not just that I have lived in New Orleans all my life and was not willing to leave my beloved hometown. One of the things that became very clear, given the technology, and also, for money, was that the organization did not have to be in New York to be a national organization. Thus, we moved our national office to New Orleans in early 2001.

- What is the current staff and budget size of the organization?

- We have eight staff members in the New Orleans office and two remote staff: Renata Petroni, who is the director of our international projects and based in New York City, and Elizabeth Doud, who is our program specialist for international projects and is based in Miami, Florida. We have two consulting staff: Bryan Graham, who does our IT and graphic designs, and Kathie deNobriga, who is our editor for publications. Our current budget size is about 2.6 million USD, about 2.1 million of which is for our national program and the rest is for the projects we are doing in New Orleans, which I can talk about later.

- Please tell us about NPN’s current programs.

- We have identified two primary purposes for our current programs at NPN. One is to support the “creation and touring” of the contemporary arts. The second is to convene our members, artists supported through our programs and like-minded colleagues to address national cultural policy issues that affect our field. We call this purpose in short, “convening and cultural policy.” All of our specific programs fall under one or the other of those two purposes.

Under the first purpose of “creation and touring,” the following programs exist: 1) the Performance Residency, 2) the Exhibition Residency (the visual arts / VAN (*4) residency); 3) the Creation Fund, which is the co-commissioning program; 4) the Community Fund, which is a flexible pool of funds for the creative process of new work, 5) the Freight Fund, which is a small subsidy for equipment of $500 or so which can be attached to the Performance Residencies, or extra-ordinary either technical or shipping costs, and 6) our international programs, i.e. “Performing Americas” with Latin America, and pilot programs that we’re working on in Asia.

Our programs are complex, because we don’t just pass along money. This relates to the “Cultural Policy.” We structure our programs intentionally to achieve certain goals. For example, The Creation Fund, a co-commissioning program, requires a minimum of two commissioners, that must be at least 100 miles apart from each other geographically, one of which has to be a NPN partner, and they have to be the applicant to us. There can be any number of commissioners, but there have to be at least two. Each co-commissioner puts up $2,000 and NPN matches it with $6,000, which is a fixed amount regardless of the number of the co-commissioners. Thus, the minimum NPN commissioning fee is $10,000. Each commissioner agrees to present the artist, presumably with the commissioned work. But we leave an out for the artists. If the work is not successful, it’s the artists’ call, although sometimes it can be the commissioner’s call if the work becomes too big. The Creation Fund is valid for three years, which means the commissioners can present the new works within three years. For some artists, that’s the amount of time it takes. Then, we subsidize the presentation by our NPN partners. We don’t subsidize the presentation by the non-NPN co-commissioners, but they have agreed by contract to present the company. So the Commissioning Fund is not just money toward the creation of a new piece, but a guarantee of at least a mini-tour of the new piece, because of the condition that there be at least two commissioners in different places.

If we look at the Community Fund closely, it is associated with either the Creation Fund or the Performance Residency. It’s broad, but is meant to basically enhance the residency activities or the creative process. If artists are developing a work with community partners, for instance, an HIV AIDS awareness organization doing story circles, they can pay an honorarium to the community organization for their participation, because it’s their time organizing story circles and their constituencies. When we kept seeing the Community Fund being used to deepen the Creation Fund projects, specifically where there were community development processes for the artists, is when the idea of the “Forth Fund” began to emerge. The Forth Fund, thus, is a new program that we just completed a pilot phase for funded by the Mellon Foundation. We are waiting to see if we have resources to launch the Forth Fund, and [if so] it will become a permanent component of and add resources to the Creation Fund. The Forth Fund came out as an answer to the question of what are the gaps in support, for the artists and for the presenters, when they were creating/co-commissioning a new piece, and knowledge that there was not much in way of resources there “in the middle” in the production phase of a new work. It’ll be a brand new subsidy pool that will enhance the Creation Fund, which is a minimum of $10,000 for the commissioning part, and maximum of $6,000 per NPN partner for presenting the work. The Forth Fund will add $15,000 to that. The way this is distributed is $5,000 to the artist’s company, $5,000 to one commissioner who has to match it with $5,000 to make the $15,000.

*4 Visual Artists Network (VAN) was launched in 2007, started in FY 2009. Currently, VAN only has residency program and not commissioning program yet. - Please tell us about the second primary goal, which is the “Convening & Cultural Policies.”

- There are very good internet meeting sites, and yet, you cannot really get to know people and build relationships with people unless you’re physically in the same room. So, the Annual Meeting is a very important vehicle for our partners. During the annual meeting we have a half-day meeting where just the NPN partners come together and talk about our own issues. We also convene an equal number of artists who’ve been supported by our programs and we subsidize the artists to attend, recognizing that there are very few convening opportunities for artists, as well as in consideration of the power dynamics. So, instead of the booking conference model of the way the presenters learn about the artists, putting them at the same table, bringing them to the same meeting, having them in the same room, so that the artists and presenters are getting to know one another on a different basis from just seeking a gig, and also so that they discuss their mutual interest in getting their work to the audience. Opportunities to talk with artists this way are also extremely important from the point of view of reflecting their voices directly in cultural policies.

The Annual Meeting is also a place for presenters to learn about new work. We have built into the meeting at least four different ways that we’re showing work. We present evening performances of Creation Fund work. We select the works based on diversity to present different disciplines, genres, regions of the country and ethnic and cultural diversity. Then, we have “Art Bursts,” which are seven-minute no-tech performances; usually solo works. They’re called “Art Bursts” because they just “burst” before the meetings. The third thing we do is a “Media Showcase,” which is a two-hour session where all of the presenters bring DVDs, or pull up YouTube clips of primarily local artists they are interested in. We sit in the room and look at DVDs together to learn about these artists. This is a way for new artists’ names to be introduced and recommended. Artists usually don’t get hired or contracted [directly] out of the media showcase, but it builds up recognition and visibility. The fourth thing we do is “In the Works.” Anybody who’s at the meeting – the artists, presenters, funders or a colleague – have two to three minutes to get up and talk about what they are working on. It’s just a verbal presentation. For example, an artist will stand up and say, I’m beginning to conceive a piece about struggles of such and such, and I’m looking for a designer who will be good to work with, or, I’m interested in finding co-commissioners, etc. We have two one-hour In the Works sessions. - How many people usually attend the NPN Annual Meeting?

- The last one in Dallas was our 25th anniversary, so it was larger than usual and about 350 people attended. Normally the Annual Meetings are attended by about 300, including the Board and Staff, 68 NPN partner members and VAN members, and an equal number of artists. We also invite 20 to 25 artists from the local community where the meeting is being held. In addition to the Annual Meetings, we also do Mid-Year Meetings. These are just for the NPN partner members and are smaller regional meetings for which we rotate the cities every year. They are attended by about 20 NPN members. Connected with the Mid-Year Meetings, we do workshops for artists called, “Doing it on the Road.” This is a basic touring practicum for artists who are interested in learning how to tour. There is a “convening function” in the International program as well. For Performing Americas, one of the curator trips is always of the U.S. presenters going to the La Red annual meeting, and the Latin American curators always come to the NPN annual meeting. The reason for the trips is the relationship building among the presenters who are going to be selecting work for the international projects.

- The current NPN structure and programs must have evolved as a result of listening and responding to artists and the field over the course of a quarter century.

- Yes, and yet one of the most interesting things for me is that the structure has not changed that much from the beginning. We came out of the alternative space movement, the idea of empowering artists and championing the artists’ perspective. But the structure that David White originally imagined and set up is pretty much still in place, although we tweaked it some.

- What kind impact did the NPN programs have on the field?

- Particularly at the beginning, we were very influential in shifting the idea of touring from just the two and a half days to the idea of residencies. I think we definitely had an influence on the idea of artists being in the community longer and engaging in the community beyond the work on the stage. For example, when Regional Arts Organizations subsidize touring, they all require residencies now, but that was not the case back in the ’70s and ’80s, and even into the ’90s.

The second big influence is the fee structure. It is a formula, but it’s based on a weekly salary, which is currently $700, plus fringe benefits, transportation, per diem, lodging, the administrative overhead to the artists. Also we have a little artistic director contingency. When a tour is being subsidized by NPN, the artists cannot charge more or less per week. Many artists graduate from NPN and then command higher fees, and yet, a number of artists who toured through NPN use our fee structure as a way to price their work in other contexts. It is not a large amount in any way, but it is a guarantee for tours along with other conditions, even including costs for child-care, in a 13-page contract. - Will you give us some examples of the artists who may be based outside of major metropolitan areas and whose careers flourished on national level due to the NPN’s programs?

- Elia Arce, for example, a Latina artist, living in California for a long time and now based in Houston, TX. When she started, she was relatively young, a solo artist. She was first commissioned by NPN in the mid-nineties, and had several Creation Funds over the years, which resulted in extensive touring history through NPN. When NPN celebrated the 25th anniversary last year, we decided to present five recreation pieces and one of them was Elia’s piece titled “the first woman on the moon,” which was one of her early solo media pieces. Jane Comfort, based in New York, was also supported through NPN in its early years. She is very vocal about the impact NPN had on her career. Pat Graney, based in Seattle, is another example, as well as Cultural Odyssey (Idris Akamore and Rhodessa Jones), based in San Francisco. There are about a thousand artists who had more than three contracts with NPN over our history. Idris and Rhodessa, in particular, are presenters as well as artists and are one of the NPN partner members. They have participated in the panel of our Performing Americas program and most recently collaborated with Latin American artists.

- Please tell us about your personal background. How did you gain all the skills in the arts administration?

- I did theater as a young child and all the way through graduate school, but I didn’t want to leave New Orleans for New York City. New Orleans is a great city, and it’s my hometown. Although frankly, there were no jobs in the arts then, or even now. We have only one Equity company, which is relatively small. Still, New Orleans is a culturally rich city in a way that, from my perspective, no place in the U.S. can come close to matching.

I was working for an art gallery when artists and others came together to found the Contemporary Arts Center (CAC). I had no arts administration training background, as they did not have arts administration programs in those days. So, it was really a case of learning on the job. We were given a huge old warehouse building rent-free, and we just took it over and did things. Part of our premise was that if we create so much activity in the building, the owner could never decide to kick us out because the public outcry will be so huge. We were providing valuable cultural resource and making space for artists. Fortunately, I was always good with numbers. I actually started college with a chemistry-major and a math minor. However, doing theatre all night and going to the lab in the morning was just too much, so I decided not to pursue a chemist’s career. I became an English major, which later came in handy for writing narratives for grants. I had a temporary job at a savings and loan company for a while when I was at graduate school, so the numbers part of creating applications and grants, part of the clerk job I was doing, became knowledge which was important later.

In 1978, there was a conference in Los Angeles. Thanks to a CAC board member with foresight, I attended the conference and discovered that there were organizations springing up all over the country like the CAC. After the founding of the NEA, it took about 10 years, but there was a great flowering and flourishing of new [arts] organizations that emerged all over the U.S. Alternate Roots (*5), which is a very valuable regionally based organization in the South, was also created around this time. The South has a particular cultural identity because of the legacy of slavery and the civil war, which is not something that permeates the culture of other regions of the U.S. in the same way. I was politically active at a very young age, both in the civil rights movement and the anti-war movement. Those experiences are the foundation of my approach to the work that I do. You’ll see in the NPN value statement, cultural equity and social justice are part of what we try to promote in our programs. This is not something I added, but has been a part of NPN from the very beginning. The idea of being local and national at the same time, of supporting the local community, leveraging opportunities for local communities, working for social justice in your local community and organizing yourselves and connecting with other people. In a way, it’s national organizing. I don’t know if that sounds like an exaggeration, but it’s sort of my approach to how I got here. After those regional and national roundtables, seeing what would be wasted and lost if NPN went away, I stepped up and agreed to become CEO to in 2000.

*5 https://alternateroots.org/ - Please tell us about NPN’s Performing Americas program.

- We apply the same Fee Structure to our international programs. There is no “Community Fund” component for the Performing Americas program, but we have “Creative Exchange” under this program, which is to conduct 3- to 5-week residencies. Performing Americas was initiated by Arts International, which lasted only three or four years after becoming an independent organization, and then NPN took it over. The core partner in Latin America is La Red, which was formed in 1991 and is modeled after NPN. For the first 10 years, La Red had funding from the Rockefeller Foundation. They don’t have any significant funding anymore and have become a “virtual organization” in a sense, but the network, which consisted of fifty to sixty members not just in South America, but in Central America and Caribbean, continues to function. The structure of the program from the beginning was intended to build knowledge and relationships, not just to support touring. We put together curatorial panels to see work and to meet our counterparts. It’s a reciprocal program, so, the presenters build trust relationships and recommend the artists for touring both ways. A panel of six NPN member partners makes ideally two trips a year, but at least one trip a year, to a festival or an event where they can see a lot of work in Latin America. Three of them as a group are intended to pick one artist, thus two Latin American artists/companies are selected for touring for three weeks, using the NPN contract model. The counterpart is the Latin American panel of two. They come to the U.S., see the work, select the artists and NPN subsidizes the tour. NPN subsides the international airfare, the visa costs, a substantial portion of the artists fees, and the percentage of the lodging, per-diem and overhead., NPN subsidizes fees for both the U.S. artists going to Latin America and the Latin American artist coming to U.S. NPN is also paying for all travel costs for the curators both ways. This is not, however, how it will work when we move into other areas. We will look for partners who will be able to raise matching money. We will subsidize part of it, but we want it to be a partnership.

- What was the motivation and background for your starting an exchange program with Asia including Japan and South Korea following Latin America?

- NPN is interested in creating programs that reflect the diversity of the U.S., and Latin America was a natural first step. When we looked at Asia, a couple of things came together, but meeting and working with The Japan Foundation was a big factor. I was on a PAJ panel of the Japan Foundation for four years. One of the things that I observed and discussed with the Japan Foundation staff is the interests of the Japan Foundation in reaching other parts of the U.S. than just New York City and other major metropolitan cities, but the fact is that the same names were showing up every year and the pool was not as big as it could be.

Corollary to this, when Consortium of Asian American Theaters and Artists (CAATA) was first being formed, they went to the Duke Foundation for funding. Duke funded their conference through NPN and asked us to mentor. Several NPN member partners became quite actively involved with them. That sort of coincided with us looking at international work. So, Asia looked to us to be a natural second area.

Also, Duke Foundation was convening their grantees internationally on alternate years, and I was invited to attend the Hong Kong International Arts Festival for a meeting. They organized a showcase of artists from Thailand, Cambodia, and Indonesia, and I saw very exciting work from those countries as well. I also learned that the Japan Foundation has an involvement in other countries in Asia, including South Korea as well, and it seemed like a great opportunity for us to reach out to other parts of Asia. I also know about the JCDN (Japan Contemporary Dance Network) very well because Nori Sato was an intern at the NPN office in the 1990s, and that JCDN is loosely modeled after NPN.

So, there has been quite an exploration over the years as we build toward taking the steps. In 2008 when the bottom fell out of the economy, it slowed things down a little, but then we were also approached by South Korea (KAMS).

We think a cultural exchange should be reciprocal, not a one-way street. Because of Performing Americas, we’ve been approached by the Dutch, the British, the Germans and the Australians. However, none of them have been as interested in reciprocal programs. The Japan Foundation and KAMS were the ones that said, yes, we agree that the reciprocal program is the right approach. That was another reason that we pursued Japan and Korea as an avenue to Asia, because of the value of reciprocity.

As per our practice with Performing Americas, we want to build a “network-to-network” relationship, which provides a structure for us to have presenters to build relationships with. Our assumption is that presenters are the avenues to the artists who are ready to tour outside of the country. - NPN’s system is that the NPN presenters (member-partners) make selections of the touring artists, not the national office. Would you please elaborate on this.

- Yes. NPN’s funding programs are not competitive, in that applications are not selected by a panel. I think that the open proposal calls and the panel systems are fine, but they are not the only way. Because they are a passive process as opposed to pro-active one, panels don’t necessarily resolve issues of inclusion and the ability of the artists who are outside of the main circles to get access. I think the systems that NPN designed are the pro-active way to have an inclusive program. Once the NPN members select an artist, that artist’s project is guaranteed NPN funding. This works for NPN because we limit the member-partners to 70 organizations. The closed network system with a limited number of members is also advantageous for enabling the members to know and talk with each other in depth.

- You’ve had a couple of trips to Japan and have seen quite a number of Japanese contemporary artists’ works. Some of such works, for example those presented through TPAM, are by emerging artists not well known even in Japan. Do you think the works you’ve seen here are a compatible match with the NPN members’ programming aesthetics?

- Yes, absolutely. Even just referring to the works we’ve seen this week at TPAM, our group is excited. Not all of the works are ready to tour in the U.S. right now but, for example, we went to a showcase organized by ST Spot and saw some very interesting and promising work there. Everybody from our group really responded to Contact Gonzo. Arnie Malina of the Flynn really liked the contemporary Noh artist at the TPAM Direction showcase. Had the language not been a barrier for the second vaudeville show on the first day, that could have been very good too. Although, sometimes, the work just does not translate. Erin Boberg Doughton of PICA, who saw a lot, was also very enthusiastic about several pieces.

- NPN’s international programs are rapidly growing, but we also understand that you have local programs for the communities.

- After Hurricane Katrina, NPN found a direct path to serve the local [New Orleans] community. We have been acting as a fiscal sponsor and an intermediary partner for artists working on hurricane recovery projects. We are channeling resources for such programs and organizations as the Porch 7th Ward Cultural Organization and Transforma Projects.(*6) There are a couple of publications (*7) that talk about various projects where artists are working in neighborhoods, with schools and groups of young people, etc., and a whole variety of ways for the re-building of the neighborhoods. It’s a very important service we’re providing locally.

I’m not sure if this is known in Japan, but the Japanese government helped the recovery efforts [in New Orleans] as well. The city of Kobe, which was hit very hard by the 1995 earthquake, in particular, shared significant knowledge and experience in recovering from natural disaster with the city and various foundations in New Orleans. They have brought groups of community leaders, educators, architects, designers and urban planners from New Orleans to Kobe to study the solutions in terms of rebuilding the city, and there’s been a lot of reaching out, for which we are very thankful.

*6 https://www.transformaprojects.org/

*7 Related publications downloadable free of charge from https://www.transformaprojects.org/ - Editorial Note

In between the time of this interview and the article, the Eastern Japan Earthquake hit. M.K. Wegmann and NPN Staff send deepest condolences and prayers to the victims and their families and NPN’s Japanese friends and colleagues. Ms. Wegmann added via e-mail from Brazil, where she was travelling on business: “I offer, on behalf of NPN, to the artists and arts organizations of Japan, any knowledge we have gained through our work in New Orleans in recovery that could aid them as they work with their communities for recovery. The creative resources of artists are powerful tools.”

M.K. Wegmann

Pioneering artist residencies and fee-structure,

Roots of the NPN strategy

M.K. Wegmann

President and CEO of National Performance Network

The National Performance Network (NPN) is a project initiated by the contemporary dance-specific organization Dance Theater Workshop (DTW) in answer to the rapid growth in contemporary performing arts organizations around the U.S. and with the mission of supporting touring artists and promoting exchanges between locally based artists across the U.S. NPN was spun off from DTW in 1997 as an independent NPO. Over the course of a quarter century, NPN has operated funding and support programs for new works and artists’ tours with its own framework based on unique strategies with about 70 NPN member-partners.

(Interviewed by Kyoko Yoshida, executive Director, U.S./Japan Cultural Trade Network)

National Performance Network (NPN)

https://www.npnweb.org/

NPN Creation Fund and Forth Fund work:

“Crazy Cloud Collection” InkBoat (under the direction of Shinichi Iova-Koga and Ko Murobushi) photo by: Pak Han

“Gloria’s Cause” Dayna Hanson photo by: Benjamin Kasulke

“Let of Think of These Things Always. Let Us Speak of Them Never.” Every House Has a Door photo by: John W. Sisson, Jr.

“Go Ye Therefore” ArtSpot Productions. Photo by: Artspot Productions

“The World Headquarters” by Dance Theatre X, photo by: Zebra Visuals

Rhodessa and Idris Ackamoor

Women of Calypso (which was the NPN Commissioned work co-produced by Rhodessa and Idris)

“Faith Healing” (Jane Comfort)

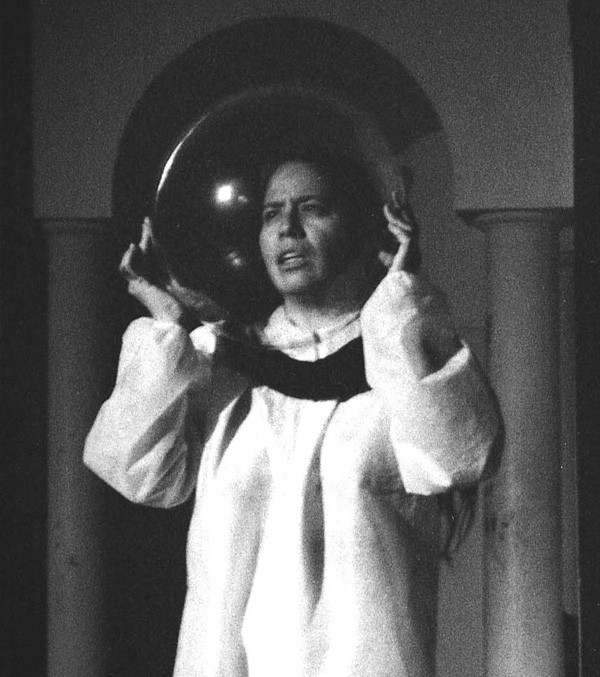

“First Woman on the Moon” (Elia Arce)

866 Camp Street (photo of New Orleans office)

Related Tags