- Could we begin by asking about the conditions the Yokohama Noh Theater opened under and what sort of management policies were adopted initially.

-

At the time of our opening there were seven Noh theaters in the Tokyo area holding performances on a regular basis, including the National Noh Theater, the Kanze Noh Theater and the Hosho Noh Theater. As a newcomer in this competitive market, we thought about what could distinguish us as a Noh theater with a truly Yokohama uniqueness and character. As a city we don’t have the long tradition of performing and watching Noh plays like Kyoto and Kanazawa. So, we decided to try to become a Noh theater that would be more open to the general public. We thought that we could develop an audience by actively teaching people about the essence of Noh and Kyogen and finding a market in new areas by proposing new ways of enjoying Noh/Kyogen. Our catch phase for this new approach was ”A Noh Theater that is accessible and easy to enter.“

The origins of Noh as a performing art go back to late in Japan’s Kamakura Period (1185-1333) and early in the ensuing Muromachi Period (1336-1573), which makes it the oldest continuing form of performing art in the world today. The framework of Noh as we know it today dates back about 600 years to the father and son playwrights Kanami and Zeami, and during the Edo Period (1603-1867) it was supported and thus preserved by the Edo Bakufu government in the form known as Shikigaku that was performed as a kind of ritual for the samurai class. Under this system, Noh performers were able to pursue their art as subsidized artists. In other words, it was not an art that depended on attracting an audience among the common people.

After the change in government with the Meiji Restoration and on through the Meiji Period (1868-1912), Noh artists made their living by taking on many apprentices and students under a hereditary family-lead school system. In this environment, most of the audience for Noh/Kyogen was the apprentices and students studying the traditional Noh vocal [narrative songs] and dance arts from the Noh masters. This made Noh/Kyogen a rather closed world that was difficult to enter for people from the general public who otherwise might want to go and see Noh performances. That is why we at the Yokohama Noh Theater decided to develop audience by ”marketing“ to a wider range of people, including people who wanted to see Noh/Kyogen as a performing art, people who wanted to learn about the Noh art for their personal education and people interested in the artistic aspects of Noh. - In your business and its ”marketing“ you always combine the four elements of performances, seminars, workshops/classroom type study and exhibitions. Also, as an outgrowth of your lectures and exhibitions, you have also dedicated efforts to media such as publishing. While keeping mainly Noh and Kyogen performances the central pillar of your business, how do you put together your programs?

-

At the Yokohama Noh Theater we pursue a three-pronged approach involving ”special performance“ aimed at pleasing seasoned Noh/Kyogen fans, ”themed performances“ with a strong thematic focus and ”new-audience focused performances“ targeting people who are new to Noh/Kyogen. In these ways we take a free-handed approach to planning the programs, and I believe that this approach probably makes Yokohama Noh Theater the only Noh theater that is constantly producing its own Noh and Kyogen productions. In order for Noh and Kyogen to survive as arts, they have to be constantly refined, and they have to be brought to the public in new forms and in new ways. To do that, we have come up with productions that approach Noh/Kyogen in new ways, such as our ”

Sotoba Komachi

as Hideyoshi Saw It“ and our series ”

Waki

and

Shite

“ (Support [Noh] Actors and Lead Actors) and our ”Rediscovering Kyogen“ series.

Also, among our ”new-audience focused performances“ we have introduced socially relevant productions such as our ”Barrier-free Noh“ that is easily accessible to the disabled as well as well as people without disabilities, ”Brunch Noh“ timed for the free time period for mothers raising children and our ”Evening Noh“ that working people can attend after working hours. With these productions we have been able to attract new audience by offering performances that better fit the needs and lifestyles of different members of society. - One of the main features that differentiates the Yokohama Noh Theater is surely this capability for innovative planning. Traditionally there has been no concept of ”producing“ plays in the Noh and Kyogen world. It was the actors who decided who they would perform with and what play they would do, and the performances would be at their own affiliated Noh theaters. In that kind of Noh world the Yokohama Noh Theater is certainly unique. Would you tell us about how you develop the concepts behind your unique productions at the Yokohama Noh Theater? In particular, your 2002 production ” Sotoba Komachi as Hideyoshi Saw It“ was very interesting as an attempt to faithfully reproduced the costumes, musical accompaniment, the [narrative] recitation and the dance all as they had been 400 years ago.

-

Basically, I believe, it is a process of creating a production concept by finding a perspective that will be interesting from the standpoint of the general public, and the ideas come from quite academic and artistic origins. We are always thinking about how to fuse the general audience’s perspective with the academic and artistic perspectives.

The concept for ” Sotoba Komachi as Hideyoshi Saw It“ came from reading an essay by the renowned Noh researcher Akira Omote (Hosei University Emeritus Professor). From his research, Omote found that in the Azuchi-Momoyama Period (1568-1603) at performance of the same Noh plays only took 60% of the time of today’s performances, and we wondered if we couldn’t try to duplicate that kind of performance to see if it was possible and what it would be like.

Noh reached it present form in the middle of the Edo Period, and has stayed basically unchanged for the 300 years since. If possible we would have liked to trace Noh back to the time of Zeami, but the lack of reference materials from that time makes any attempts to define what it was like in that age mostly speculation. We knew that we could trace its forms back to the Momoyama Period with some accuracy, however. There are about 2,000 plays in the Noh repertoire and some 220 to 230 of those are performed today. But we can only find reference to about three of these being performed in the Momoyama Period, and Momoyama Period is one of them.

Sotoba Komachi is what is known as one of the ”heavy Noh plays.“ By the way, the categorizing of Noh plays into heavy and ”light“ ones is a concept that emerged in the Edo Period after Noh became a ”ritualized“ theatric form. We thought that if we could re-produce the Sotoba Komachi of 400 years ago and compare it to the way it is performed today, we could get an idea of what Noh was like before it became ritualized and was performed more freely as a performing art.

To re-produce the play as it was performed 400 years ago with as much authenticity as possible we enlisted the cooperation of Waseda University prof. Mikio Takemoto in the field of Japanese literature, the Head of the Intangible Cultural Properties Section of the National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Tokyo, Izumi Takakuwa in the field of music, and shite (main character) performer Nobuyuki Yamamoto. Also, we asked for the assistance of assistant prof. Kiyoe Sakamoto of Tamagawa University regarding re-creating the intonation of Kyoto dialect in the Momoyama Period.

For the costumes, Akira Yamaguchi, director of the Yamaguchi Noh Costume Research Institute, referred to scroll paintings in the collection of Kasuga Shrine in the city of Seki in Gifu Pref. to recreate the costumes. In order to use the same kind of silk for the costumes as used in the Momoyama Period, they began by raising the silk worms in making the thread in the old way, and for the gold leaf and embroidery, old methods from the Edo Period were used.

When it came down to the actual performances we performed the play twice, first in the contemporary style and then in the re-created Momoyama form. The contemporary performance was about one hour and 40 minutes [as usually performed today] and the Momoyama reproduction was performed in just over 50 minutes [according to the 60% calculation]. When we actually did the Momoyama version in that time, it turned out to have a very nice tempo and a clear sense of dramatic development that was very enjoyable to watch. People often say that watching Noh makes them sleepy, but the reactions we got from the audience after watching the Momoyama version performance were things like, ”I didn’t get sleepy“ or ”It was [more] interesting.“

In all we spent one year in the research and a total of two years for the production of that play. The rehearsals began with explaining to the performers about the intent and the differences the performance would involve. Then some parts were rehearsed separately and finally there were three or four full rehearsals with the entire cast and crew. Considering the fact that there is usually only one ”rehearsal“ where all the performers and crew get together to prepare for a normal Noh performance today, it was surely an unaccustomed work load for those who participated in this [” Sotoba Komachi as Hideyoshi Saw It“] production, wasn’t it? What’s more, performing at the speed of Noh as it was performed 400 years ago meant that the performers would have to completely break out of the [slower] tempo that they have trained themselves to perform with in normal contemporary productions of new or revived Noh plays. - I’m sure it was quite a burden for them, because everything from the rhythm of the recitation and music to the intonation of the verses had to be changed. There were some who objected that their art is one of training themselves in ”forms“ through repetition and performing at the faster tempo would be a process of undoing what they have worked hard to train their bodies to do.

- I believe this was a production that had a big impact on both the performers and the audience and brought together all of the know-how that the Yokohama Noh Theater has acquired.

- I feel that this production was made possible because of all the things we had experimented with until that time. After the Yokohama performances there were plans for it to also be performed at the 400-year-old Noh stage at Nishi-Honganji temple in Kyoto, but unfortunately that plan was never actually realized.

- Still, it was revolutionary in the way it brought the results of academic research to the stage, wasn’t it?

- Yes, it was. I believe it is safe to say that serious research of Noh began after WWII with researchers like Akira Omote and Mario Yokomichi at the forefront. Until now, however, the research was mainly restricted to its study from the standpoint of Japanese literature but not comprehensively from the perspective of Noh as a performance art. Although there had been research in specific areas such as re-creating the way the narratives were recited in Zeami’s day, there hadn’t been attempts to re-create it comprehensively as a 3-dimensional performance art. I feel that one of the roles of producing in the field of Noh can be to undertake experimental productions like this.

- What is important for realizing Noh productions of this type?

- You have to have a solid concept, and then you need a network of people to help you realize it, I believe. First of all a good concept is essential and then we think about who the right performers will be and which specialists you should consult with. In other words, it is a combination of the right elements.

- Due to the established presence of distinct schools and styles in the traditional Japanese performing arts that are mainly handed down through certain families, it would seem like quite a difficult thing to cross those divisions and get performers of different schools and families to perform together in the same production.

-

It is meaningless if crossing over the existing boundaries of school and style is your only aim. You have to have a clear reason why two performers of different schools still make the best combination for a given production.

Noh performers already have their hands full with the task of perfecting their art within the existing plays in the existing styles, and working up a new play on top of that takes a lot of additional effort. So, you have to be able to give them a very good explanation with sound reasoning why doing a new production is meaningful and what it will contribute to Noh and Kyogen. To convince the performers of that importance you need a clear concept that they will appreciate, and it is also important that it be one that the audience will understand, too.

The production ”Buke no Kyogen, Choshu no Kyogen“ (Kyogen of the Samurai Class, Kyogen of the Townspeople) for which we recently received the Excellence Award of the Agency of Cultural Affairs Arts Festival, was designed to show the audience the differences between the Kyogen of two families of the Okura school of Kyogen, the Yamamoto family of Tokyo and the Shigeyama family of Kyoto. And it was very gratifying for us when we received words of thanks from both Yamamoto Tojiro sensei (master) and Shigeyama Sennojo sensei afterwards for planning that production. That kind of expression of gratitude from the performers is extremely encouraging for us as producers. - But isn’t the number of people in the world of classical arts who appreciate these kinds of new productions rather limited?

- Perhaps, but even if certain productions are successful, it is not good for us to continue to plan productions for the same group of performers. If we do that, our network will not continue to expand, and it won’t lead to new discoveries. Certainly there are performers who we feel safe using, but we can’t let ourselves fall into easy patterns like that. So, we are always aware to keep attempting new projects.

- Twelve years have passed now since the Yokohama Noh Theater opened. Do you feel that the concept of producing like you have done is catching on in the world of Noh?

- I don’t think we are the sole influence in this trend, but it does seem to me that there is a growing appreciation of the need for original producing efforts. Producers should of course always be trying to bring high quality, interesting productions to the stage, but I believe that the essence of producing is getting as many people from the general public to come see the performances (in other words how you show Noh to the general audience). Performers always comment about how large (full) the audiences are at the Yokohama Noh Theater, and I believe that it is essential to keep coming up with productions that are successful commercially in that way.

- At the Yokohama Noh Theater you also actively present other traditional arts and folk arts. In 2007 you did a production called ”Two Dojoji ’s“ that brought to the stage the Noh classic Dojoji and an Okinawan kumiodori (traditional ethnic group dance) adaptation of the same play called Shushinkaneiri .

-

I believe that Japan is a country with a rich tradition of different arts not seen in other countries. There are highly sophisticated performing arts and also a great diversity of regional folk arts that have been preserved at a very high level. And I don’t think the Japanese people are sufficiently aware of this wonderful cultural wealth. All of them are highly unique. And one of these traditions is the

kumiodori

dance theater of Okinawa.

In the past, when Okinawa was the independent Ryukyu Kingdom (1429-1879) that shared political relations with both Japan and China, and unique culture flowered as a result. Kumiodori is the form of dance theater that developed as entertainment for emissaries from China called Sakuhoshi visiting the Okinawan royal court at Shuri-jo castle. It is said that kumiodori was established in 1719 by the royal magistrate of dance, known as the Tamagusuku chokun , combining elements influenced by Noh and Kabuki. In the past it was performed on a stage with a hashigakari (entrance bridge) similar to a Noh stage, but other details of the art were lost with the fall of the Ryukyu Kingdom and the devastation of the Second World War.

For that production we asked the Noh performer Umewaka Rokuro (now Umewaka Gensho to direct Shushinkaneiri with the aim of searching for what the play was probably like when it was performed on a Noh-like stage with a hashigakari and with hopes that there would be new discoveries within the kumiodori genre by approaching through the filter of Noh. In the past few years the Yokohama Noh Theater has further broadened its scope by looking overseas through programs such as your exchanges with traditional arts of Asia. -

Since the time of our opening there has been an awareness at the Yokohama Noh Theater that despite our central focus on Noh/Kyogen we should be a center that strives to stimulate other Asian traditional arts as well. But, since our theater is a Noh theater, there are things that we can do and things that we can’t, we decided that for the latter we could work in venues outside our own theater.

A significant turning point in these efforts came in 2000 with our 3-year ”Korean Traditional Arts Festival.“ This program originated when Yamamoto Tojiro sensei came to us after a Kyogen performance tour in S. Korea and said that there were traditional artists in Korea who wanted to perform in Japan, and could we talk with them about making it happen. The resulting program continued for three years. The first year we invited some of the very top class performers in Korea, and we also had Tojiro sensei performing. In the second and third years we had an exchange program in which top artists from Japan and Korea performed the same programs in Yokohama and Seoul. Our thinking for this project was that it would be meaningful audiences in Japan and Korea to deepen their mutual understanding by seeing the same programs of performances. At the time this project started, Korea was still a ”close but distant neighbor country“ unfamiliar to many Japanese, but word got around that the best Korean performers were coming and every day the afternoon and evening performances were all sold out. After that the ”Korean Boom“ began in Japan [sparked by Korean TV dramas broadcast by the national television station NHK] and suddenly S. Korea was a ”close and familiar neighbor country.“ Seeing this dramatic change impressed us anew with the power of culture.

The different peoples need to understand the classic and traditional arts of their respective countries and ethnic groups, but if that is allowed to go in a direction where people come to think that their own country’s or ethnic group’s classic and traditional arts are the best, that is only a narrow form of nationalism. The classic and traditional arts of each country are full of the ethnic uniqueness and spiritual character of its people, and coming to understand those arts of a given country is a big step toward understanding the country itself and its people. I have come to the point where I now want to use the classic and traditional arts as a tool for promoting understanding of one’s own country and other countries in ways that make the arts a bridge toward mutual understanding between peoples and nations.

In 2005, we gathered traditional dance artists from Japan, S. Korea, Bali and Thailand for a project in which we asked a contemporary theater director to help them create a collaborative work, and what we found is that the individuality and uniqueness of each country’s dance traditions is so strong that it is difficult to create a joint collaborative work. We are doing joint works with other Asian countries again this year, but this time I want to make it a sort of omnibus program in which the individual performances are connected by a Kyogen-style oratory in device known as kyogen-mawashi .

Also, this year we are having a program titled ”Joint Performance of People of the Land“ ( Daichi no Joint Performance ) in which performances of works by a young performance group of Japan’s indigenous Ainu people will be held together with performances by a Canadian Indian artist. From Canada we have invited Santee Smith, an artist who uses her experience in ballet and contemporary dance to create works that explore and express her identity as a native Canadian.

When I went to meet with her in Toronto, there was a native Canadian arts festival going on and I was truly inspired to discover the variety of wonderful aboriginal arts. Prior to that I had tended to look at the arts from the perspective of East and West, but that experience renewed my conscious that there is also a world of indigenous ethnic groups in each country. What these traditions all have in common is a ”lifestyle of coexistence with nature.“ The Japanese Ainu world is one of these traditions. So the program is titled along those lines.

Before the performances, we will hold lectures to give the audience a better understanding of the respective cultural and historical backgrounds of these two ethnic groups, and the next the artists get together for a workshop. Thus, the program involves the audience and the artists in ways that promote deeper mutual understanding. With this as the foundation, we hope to move things in a direction that will enable the creation of a collaborative work between the Ainu and Indian artists. And then, hopefully, we can take the resulting work for performances overseas. - This year there will be a large variety of commemorative events celebrating the 150th anniversary of the opening of the Port of Yokohama, and the Yokohama Noh Theater has organized an exhibition for June titled ”Noh Costumes that Crossed the Seas.“ Can you tell us something about what this exhibition involves?

-

Since the opening of Japan at the start of the Meiji Period (1868-1912), many Noh masks and Noh costumes from the Edo Period (1603-1867) and earlier were taken overseas by collectors and found their ways into the collections of museums in North America and Europe. One such collection of Noh costumes is in the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus in Munich, Germany. This is a museum occupying the mansion of the wealthy portrait painter Lenbach of the Bismarck era, and since it is not a museum specializing in Asian art, its curators didn’t really know the value of the Noh costumes in its collection. This collection was discovered by the Noh costume researcher Yamaguchi I mentioned earlier. When we heard about this, we made a plan to bring the collection back to Japan for restoration and, while it was here, to make re-creations of the costumes and use them in a Noh production.

Studying the costumes some old records were found revealing the interesting fact that they had been used at the time as costumes for the operetta Mikado (*) . Because the title referred to the Emperor of Japan, it was considered disrespectful of the Imperial Family in prewar Japan and thus banned from being performed here. In fact, however, it had actually been performed in Yokohama’s ex-patriot district in 1887 under the title ” Sotsugyo Shita Sannin no Otome “ ( Three Graduated Debutantes ). Considering this fact as well, we decided to produce a performance of Mikado .

The operetta will not be held at the Yokohama Noh Theater but at the Yokohama Kaikou Memorial Museum that was built in 1917 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Port of Yokohama. This is one of the representative buildings remaining in Yokohama that was built in the pseudo-Western style of that period, so don’t you think it is interesting that it should be the site of a performance of an operetta that reflected the Japonism movement that had such a big influence on Western culture a century or so ago?

We also plan to hold the exhibition of Noh costumes in Germany, and we hope that it will promote an understanding of the fact that Noh costumes are not just expendables but meaningful works of art in themselves and also an understanding of the cultural and historical backgrounds. We won’t be able to put on a performance of Noh but we will provide a video for the German audience to watch. - What kinds of things do you plan to do for the future?

-

We have two key words that will be guiding our plans for the future. They are ”soft power“ and ”multiculturalism.“

Soft power is a concept of international politics put forward by Joseph Nye, who is designated to be the next U.S. ambassador to Japan. It proposes that when a country wishes to exert influence on other countries or the international community, it is important to not depend solely on the traditional ”hard power,“ exemplified by military power, but to also employ the various forms of ”soft power,“ as exemplified by the arts and culture. It assumes that the arts and culture have the power to change the world.

The arts and culture also have the potential to be used as tools to combat the problems such as poverty, the environment and stimulating economic growth that face today’s society. I want us to promote projects that use the arts and culture as a means to address these social issues. It does not have much appeal if we just ask potential sponsors to provide funds simply for ”art for art’s sake.“ From now on we have to be able to say to them, ”Art can be used to solve such-and-such a problem.“ I want to be able to show them specific plans that demonstrate ways that art can change society.

Also, I believe that the classical and traditional arts are very useful for promoting mutual understanding between peoples in today’s globalizing world. Because discovering the cool or fascinating aspects of another country’s culture can turn people’s opinions and sense of value around 180 degrees. That is the meaning and value of ”multiculturalism.“

As part of these efforts, I want to provide the means for people of various ethnic backgrounds living in Japan today to be able to show their arts and culture to audiences, such as the Japan-resident Koreans, Chinese, Brazilians and Vietnamese. There must be many such people living in Japan today who have the ability to perform their unique ethnic arts. I want to search these people out and give them opportunities to perform and develop their arts. A lot of regional ”interior culture“ also exists in Japan, and I want us to provide the opportunities for more people to realize and appreciate this culture.

In the classical and traditional arts exist a precious core that represents the essence of the performing arts and spiritual substance of their respective country or ethnic group that have been nurtured over many generations. The important thing for us is to think how we can present these arts with positive impact and without destroying that precious core.

It is important to realize that, unlike producing contemporary arts, the traditional performing arts represent a vast accumulation of essence from the past. In that essence it is possible to find new potential for the future. To present them in a way that makes that potential accessible requires a lot of knowledge that enables one to present them within the proper framework and, basically, I believe that a true producer is someone who has the ability to put forward missions and concepts and then do the simulations necessary to bring them to the stage successfully.

Masayuki Nakamura

As the Yokohama Noh Theater ventures into the uncharted field of traditional arts production, attention focuses on its planning expertise

Masayuki Nakamura

Chief Producer of the Group for the Promotion of Cooperation of the Yokohama Municipal Arts Foundation; Assistant Director of the Yokohama Noh Theater.

Born 1959. After working in the private sector, Nakamura started working for the Yokohama Municipal Arts Foundation in 1991. He has been involved in the Yokohama Noh Theater since it opened. The publication of his book Issatsu de Wakaru Nihon no Dento Geino introducing Noh/Kyogen, Kabuki, Bunraku, Gagaku Kagura, traditional Japanese dance and variety entertainment is scheduled for the end of February 2009 from Tankosha Publishers with English translation.

* Mikado

This is an operetta that premiered in London in 1885. It was created within the Japonism boom that occurred after the holding of a Japan Exposition. It was written by William S. Gilbert and the music composed by Arthur Sullivan. It is a knockabout play that takes place in a fictional country and includes satire of the British high society and the servant class. According to the History of Japanese Opera by Keiji Masui, there were frequently productions of Britain’s popular Gilbert and Sullivan plays in Yokohama, due to the city’s large British expatriate community. In 1887, two years after its London premiere, the Saliger Company came to Japan and gave performances of the play at the Yokohama Public Hall on April 28 and 30. Due to the fact that a “Mikado” appears in the play and the title, implying the Emperor of Japan, the title was changed to Sotsugyo Shita Sannin no Otome (Three Graduated Debutantes) and some modifications were also made in the script to avoid disrespect toward the Imperial Family. After that, performances of the operetta were banned in Japan until after World War II.

Yokohama Noh Theater

The architecture of the stage in the Yokohama Noh Theater was originally built for the estate of the lord of Kaga-han (today’s Ishikawa Pref.), Maeda Nariyasu, in the Negishi district of Tokyo in 1875 and later moved to the estate of Matsudaira Yorinaga in the Somei district of Tokyo where it was used for Noh plays until 1965. It is the oldest existing stage in the Kanto region and 8th oldest in all of Japan. And it is the oldest stage in all of Japan that is still being used regularly for Noh performances. “It naturally has great value as a cultural asset and it is especially valuable because it is a stage that has gained additional value because of its constant use over such a long period, ” says Nakamura. It is now registered as a Tangible Cultural Asset of the City of Yokohama.

Main Awards:

“Sakika” Award (2004)

“JAFRA Award” (Ministry of Internal Affairs Award) (2006) for innovative public sector facilities.

“Excellence Award of the Agency of Cultural Affairs Arts Festival” for the planning and staging of “Buke no Kyogen, Choshu no Kyogen” (Kyogen of the Samurai Class, Kyogen of the Townspeople)

Location: 27-2 Momijigaoka, Nishi-ku, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa 220-0044

https://yokohama-nohgakudou.org/

Photo: Shigeru Takao

” Sotoba Komachi

as Hideyoshi Saw It“

(Nov. 2002)

Difference in costumes (above is the contemporary version costume and below is the Momoyama Period version)

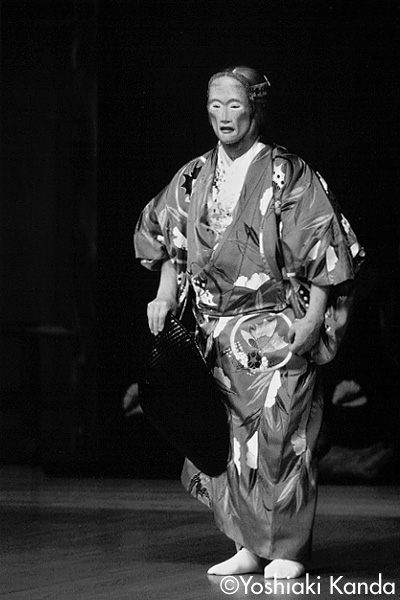

Photo: Yoshiaki Kanda

Okinawan

kumiodori “Shushinkaneiri”

Noh

Dojoji Akagashira Nakanodan-kazubyoshi Kuzurenoden

Futatsu no Dojoji

(“Two Dojoji’s”)

(Apr. 2007)

Photo: Yoshiaki Kanda

Related Tags