- Can you tell us about the organization of the Beijing Modern Dance Company?

- We have 28 members. Eighteen of them are dancers. The remaining ten are the production team, including technicians, costume designer, international coordinator, publicity and administrative staff.

- What types of people do you have among your company’s dancers?

-

In age they range from 20 to 32. They are all university graduates with Bachelor degrees in the arts. As a result, the Beijing Dance Academy even blames us for taking all the best people [from them]. At this year’s Taoli Grand Prix, both the Gold Prize and Silver Prize went to dancers of our Beijing Modern Dance Company. Having been educated at the universities, our dancers have a solid base in their art and they are all at the same level in terms of training. However, in general they lack breadth of perspective in the beginning. That is why I try to take them to [international] festivals whenever I can. If they find new types of expression there, then they can bring that into their own work. Since our dancers have a good basic foundation in dance, they are very fast to learn new things, compared to dancers who don’t have such a foundation.

Among our dancers are some who have sought us out and some who we have recruited. In China there are not many chances for dancers to perform, so they are looking for opportunities. But, they don’t want to work in the [commercial] entertainment field, such as dancing at nightclubs. What is hardest for dancers is not making a living but the fact that they don’t have fellow dancers and a good environment to dance in. If they can find a good environment in Beijing Modern Dance Company it is natural that they will want to join us. - About how many performances does your company give a year?

- Between 50 and 60 stages. It would be easy to increase the number of performances, but by spending most of the time on developing works, we seek to concentrate on the quality rather than the number of stages we present.

- I believe you had an artistic director in the past. Do you have a stage director?

- In the past we brought in an artistic director from Hong Kong, but we don’t have one now. In 2005 we had an opportunity to review our operations and we decided that an artistic director was not necessary. Now our dancers create works themselves. They do their own choreography. Titles such as artistic director are nothing more than names people have made up. And, when you start giving people titles it tends to lead to trouble, as they try to exert their powers. The reason I chose the general English title “director” instead of the traditional Chinese title “company chief” is because I wanted to get rid of these types of specialized positions within an organization and the absolute power they involve. The reason I came to Beijing Modern Dance Company in the first place was to reform that kind of monopolization of power and specialization of organizational roles and titles. Beijing Modern Dance Company is now an open organization in which things are decided democratically.

- In October, 2006 you held a tenth anniversary production titled “Beijing Vision” at which you performed five our your representative works. They were very different and unique and covered the full accomplishments of the company so well.

-

The 1996 work

Red and Black

is one from before the time I became involved in the company and Jin Xing was the artistic director. It is a work that she choreographed and it uses a black and red color scheme and traditional Chinese cultural symbols like the fan and drum. The music is Chinese ethnic music. It was a production that declared the founding of the Beijing Modern Dance Company. The 2004 work

Flower

is one for which the music was composed by the pioneer of Chinese rock music, Cui Jian. It is a solo for a young male dancer. The choreography was by Gao Yanjinzi (presently an artist with the Beijing Modern Dance Company). The 2004 work

Jue / Aware

was one invited to the Berlin Arts Festival. It was again choreographed by Gao Yanjinzi and was a mother-daughter production done in collaboration with her mother, who is a dancer. The human body is used in this piece to express complex relationships of the traditional and the contemporary, how they are passed on and developed, how they borrow from each other.

Since 1999 you have been organizing the Beijing International Dance Festival, I believe. What is the situation like for the Festival now?

- I am glad to say that we have won acclaim each year and continued to grow, but it is also the case that size and quality are mutually opposed quantities. From the outside it may look like we are successful, but on the inside there are a variety of problems. The SARS outbreak in 2003 provided us with a ripe opportunity to think about the direction of the Festival again.

First of all there is the fact that a festival simply takes a lot of money. But we don’t have that money. Because we have been expanding the festival every year despite the fact that we don’t have money, the overall quality has fallen of necessity. Secondly, there is not sufficient planning going into it. Since we didn’t have money, we were accepting all the performances that came to us and not turning any away. As a result, it had become simply an event with no particular academic or artistic merit to speak of. Thirdly, the development of the Beijing Modern Dance Company was not keeping pace with the growth in scale of the Festival. That meant that we were unable to devote sufficient organizational resources to the Festival, and if something like an accident in which people were injured should happen, we would be unable to handle it. Considering these factors, it seemed better that we not organize a festival at all.

Looking to the future, we plan to take another look at the status of festivals in China and clarify the definition of what they should be. One thing we are think now is that our Festival should be themed. Even if everyone involved doesn’t necessarily know about it, there must be a theme that all the important members of the organizing group recognize and understand thoroughly. Next comes the composition of the program. We have to decide what percentage of the total program should be dedicated to the established masterpieces in order to maintain the quality of the festival. Then we have to decide what percentage of the program to devote to progressive works present that may point the way for the future. And as a festival, we also have the responsibility to give a chance to some unknown “dark horses” that may turn out to be good. The third thing we have to think about is tie-ups with other festivals. Tie-ups with other festivals raises the scholarly value and provides scholars with new material for their research. The results of their research will then provide material for new outlooks for the future that benefits both them and us. The analysis of scholars also helps to provide the general audience new understanding of the arts. The networking through Tie-ups can also help cut costs.

The Beijing International Dance Festival we held last October and November gathered eight companies from Chinese cities including Beijing, Shanghai and Guangxi and ten overseas companies primarily from the countries of Europe. Our five venues included both theaters and outdoor arenas. We also held lectures and workshops.

There was a considerable amount of experimental work involved in the production we invited to our last Festival. That was because we were introducing a new style of work. At first, many of the works by the European companies were new works, so there wasn’t much in the way of detailed materials or documentation about them. That meant we couldn’t get government approval. But I wanted to bring in some new work. So, what I did was to choose a work by the internationally famous Danish Dance Theater, which always has a lot of experimental elements in its works. After their performance, there were people in our audience who were saying that it was not art. Of course, we had expected to hear that. But, this is the type of work that should be studied by the scholars, and I believe that it is the role of a festival to put this type of experimental work out in front of the audience and the critics and scholars.

It is easier to invite this type of experimental work as part of a festival rather than as an individual performance. In short, if you invite it independently you are going to have to provide the officials with a lot of reference materials about it in order to get approval, but if it is part of a festival it is only one small part of the overall plan. Our 2006 Festival was very well received and that led the government to offer funding for the 2007 Festival. For the 2007 Festival we are going to put a lot of effort into the planning and organizing.- How do you decide what works to invite from overseas?

- Sometimes the foreign companies contact us and sometimes we go to them with a request. Up until now we have presented over 1,500 stages and some of them have been very memorable, outstanding works. When I discover works like these I want to find a way to bring them to China, and what I usually do is to contact that country’s embassy. One of the roles of an embassy is the export of their country’s culture, and they are usually prepared to use part of their budget to do that. This is how I have found it to be with almost all the embassy staff I have dealt with, although it varies somewhat by country. What I tell them is that we want to help them export their culture. Then I tell them that they don’t need to give us any money. Instead, I ask them to give the money to the artists we will be inviting.

Now I am on very friendly relations with many of the people at the embassies. And because of this they will often tell me what their annual budget is. For example, they may say that their budget isn’t large this year but they have enough to support performances by four companies, and then they ask me what companies I am interested in. In this way, it is getting easier and easier to get foreign performers to come here.- What things do you pay special attention to in foreign exchanges?

- Trust is the most important thing. I have to make sure that our foreign partners don’t get a mistaken image of China. So I am very careful to make sure that everything is done legally according to the existing laws. How did the Beijing Modern Dance Company come to be established in China at a time when there were only public sector arts companies?

- First the legal procedures for the establishment of the company were made, even though at the time the company only had eight dancers. The director of the Beijing Bureau of Cultural Affairs was a person with very progressive ideas, and he believed that Beijing should have a contemporary dance company. The Beijing Modern Dance Company got its start when eight of the first graduating class of the contemporary dance department of the Beijing Dance Academy were given Beijing residency so that they could remain in Beijing. Although they were called the Beijing Modern Dance Company, they weren’t actually an independent company at first. They were under the management of the Beijing Song and Dance Company and they were using the performance rights of the company without one of their own. And, although there was some budget provided for them by the government, it was allotted through the Beijing Dance and Song Company. In other words, the Beijing Song and Dance Company as managing the Beijing Modern Dance Company in place of the Bureau of Cultural Affairs. So, at the time of its establishment in 1995 it was actually a public sector company. And, I wasn’t involved at that time.

- When did you become involved with the Beijing Modern Dance Company?

- In 1998. At the time the Beijing Modern Dance Company was at a critical stage in its existence. The government wasn’t taking any responsibility for it and it was on the verge of becoming defunct as a result. Although the government had said that Beijing needed a contemporary dance company, they were reluctant to get involved when things got difficult. There were various problems, including financing. I happened to know the dancers well and I suggested to them that they wait for a while and see how the situation developed. Three months later I found out that they had all left the Beijing Modern Dance Company and were dancing at a nightclub to earn their living. That is a tough thing for a dancer to have to do. When I went to the Beijing government to talk about the situation, they told me I should manage the company. I wanted to help them but I was already managing several businesses at the time and I just didn’t have the time to take on more responsibilities. After thinking about it for a while I decided that I could afford to provide the dancers’ salaries and I got some friends to put up several tens of thousands of Yuan (several million yen) to fund them. We were fortunate to have the capital at that time.

Of course this was not a fundamental solution to the problem. The problem was not the financing but the fact that there was no real management and planning. After thinking about what I could do for the Beijing Modern Dance Company, I decided to become involved. Now eight years have passed. I never thought I would be involved with the company this long. With the exception of one, all the dancers in the company now are different from the original members. As you know, that remaining one is now my wife, Gao Yanjinzi. I am now concentrating fully on managing the company. I am not involved in any other business at all. Lately I find myself thinking that people like me don’t choose the work they do but it is rather the work that chooses us.- After that, how did you make the Beijing Modern Dance Company an independent private-sector company.

- The first thing we did was to get rid of the requirement that only people with Beijing residency could be members of the Beijing Modern Dance Company. Then we replaced the traditional Chinese system of employment by introduction with a contract system. Next we stopped depending on government funding. We even turned to renting our own studio space. At first it was a studio formerly used by the Beijing Song and Dance Company that had managed the Beijing Modern Dance Company, but we made a point of paying rent for its use. The reason for this was that we wanted to have decision-making rights in all aspects of the company’s management in order to become a truly independent company without government affiliation or obligations. As you probably know, in China if you have government affiliation you will be obliged to give priority to government-organized events even if they conflict with important events that you might have been planning at the same time. If you have full decision-making rights, however, you can refuse such priorities. On the other hand, if you are in a situation where you are not depending on government funding and you go abroad with government officials to present a production, they will provide funding for it. Since we are not financed by the government we have to think about how to get by when there is no funding. We have had the good fortune of accompanying the Chinese President Hu Jintao with one of our overseas performances and we received a good amount of compensation from the government that time.

In this way we became what you can call an independent private-sector company, but in fact we are not completely independent. This is because, as I’m sure you know, in China a performance permit is necessary in order to give public performances. At the time, Beijing Modern Dance Company didn’t have a performance permit of its own, so in order to perform we needed to use the permit of another organization. We couldn’t perform on our own merits. It took me three years of hard work to get us this performance permit. On June 27, 2004, we finally got our permit. That is why I was able to say that the Beijing Modern Dance Company was a completely private-sector company when I came to Japan for the Tokyo Arts Market in the summer of 2004. And what we had received was a permit for commercial performances, which was unprecedented for a contemporary dance company. Even the Guang Zhou Contemporary Dance Company that was established earlier than our company is still receiving government funding. Throughout China, we are the only completely independent private sector arts company that has this performance permit.- With 28 company members, how are you able to keep the company going without government funding?

- We actively participate in international festivals as a means of publicizing our work. If promoters like our work and want to schedule a tour of performances we get a good amount of income from that. If we do 30 performances we are able to earn about US$500,000, and even when we deduct our various expenses we are still left with a considerable amount. Besides, we live simple lives and we don’t require a lot of money. So, we are able to make enough to support ourselves.

We have contracts with our dancers of at least one year and pay them a fixed monthly salary is 4,000 Yuan (approx. US$515), which the equivalent of the starting salary of white collar worker with a college degree in Beijing. In addition we give them a housing allowance of 500 Yuan (approx. US$64) and pay for injury insurance. We also pay an additional fee of at least 200 Yuan (approx. US$26) per performance aside from their fixed salary.

That may seem like a stable situation but I cannot afford to feel satisfied yet. The next ting I plan to do is to look for some fixed sponsors for the Beijing Modern Dance Company. There are busy times and inactive times with few performances in the performing arts, so we are susceptible to economic insecurity. Things will become more stable if we can get some fixed, long-term sponsors. I would like to get sponsorship not from just one source but from about ten. Then it will be sufficient if each sponsor gives us about 100,000 Yuan (approx. US$13000).- Are you interested in inviting Japanese performers at your Festival?

- Lately there have been political problems between Japan and China, but that doesn’t apply to the arts. If the opportunity presents itself, I would like to participate in the festivals. I am personally interested in the work of Kazuo Ono and Sankai Juku.

- I am glad to say that we have won acclaim each year and continued to grow, but it is also the case that size and quality are mutually opposed quantities. From the outside it may look like we are successful, but on the inside there are a variety of problems. The SARS outbreak in 2003 provided us with a ripe opportunity to think about the direction of the Festival again.

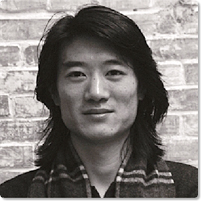

Zhang Changcheng

What lies ahead for the Beijing Modern Dance Company and its international dance festival in today’s Chinese contemporary dance scene?

Zhang Changcheng

Beijing Modern Dance Company Director

The Beijing Modern Dance Company was the first private-sector arts company ever to be granted performing rights in China. Its productions and organization have grown significantly in the ten years since its founding in 1995. The man behind these accomplishments and the company’s active foreign exchange is the director Zhang Changcheng.

Red and Black

(1996)

© Zhang Heping

Flower

(2004)

© Zhang Changcheng

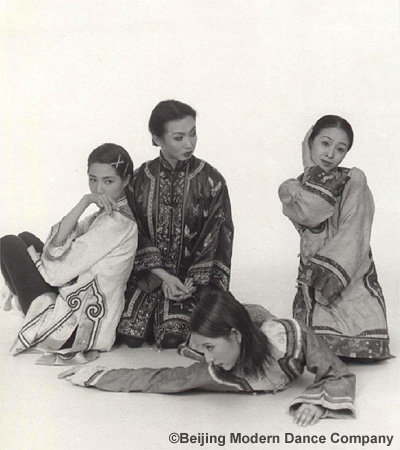

Four Happiness

(1996)

© Beijing Modern Dance Company

Quietude

(2003)

© R PRODUCTION

Jue / Aware

(2004)

© R PRODUCTION

Related Tags