- Please tell us about the founding of the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre.

-

The Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre was founded on Jan. 23, 1995. It was formed from a merger of the Shanghai People’s Art Theater and the Shanghai Youth Drama Troupe. The Shanghai People’s Art Theater was a theater company established in 1950 by the pioneers of modern Chinese theater, Xia Yan and Huang Zuolin. The Shanghai Youth Drama Troupe was founded in 1957 by one of the founders and former president of the Shanghai Theatre Academy, Xiong Foxi. Both of these are thus institutions with a history of roughly half a century.

However, with the start of reform and liberalization in China and the shift to a market economy, both of these institutions had a difficult time making the transition. The biggest causes were the loss of audience and the number of productions they were able to mount a year, which resulted in a drop in the number of performances. The reasons were clear. It was the diversification of culture that accompanied the changes in the social systems. The effects of the new market not only cause a loss theater audience but even the theater staff itself was drawn off to film and television work. Watching these changes, we realized that the institutions could not survive under to old managerial methods, and that is what led us to merge the two. - What kinds of reforms were implemented after the merger? And what effects did those changes have?

-

Both were theaters with long histories and bases in their traditions. Even though they had fallen on hard times they were still first-class theater companies. They did have their problems but all we did was change the management system. Before the merger the theater directors made all the decisions, they handled everything from the production of the works to business management of the companies. That kind of closed management system was stable and effective in the days when theater was not subject to market pressures. However, this kind of central administration is not suited for an unstable environment full of change. We decided to shift the responsibility for production from the theater director to a producer who specialized in that role. As with a film or television producer, this producer is one who produces works in the sense of a creator. As a Managing Director under this kind of managerial system, my primary role is to help promote this production of theater works. I have the decision-making rights regarding the supply of financing and personnel for productions and the authority to choose the producers for each production and in these ways energize the organization. By appointing producers we have now created production groups within the organization. Under the previous system the theater director decided everything from the production of works to the entire range of matters involving the members of the company, from ceremonial events like weddings and funerals to welfare benefits like health insurance, pensions. But, creating works of art is a mission for those who are able to dedicate themselves to an extreme pursuit of artistic essence, while administration of health and welfare programs is a job that requires a strict adherence to fairness and equality. It is certainly not effective to have one person performing two such completely different roles as these. That is why we decide to divide these roles into separate positions.

Eleven years have already passed since the founding of our Center in 1995 and we have achieved great results during this period. We have created about 200 productions during this time, with an average of 20 productions per year. Before the merger, the two companies together only averaged seven or eight productions annually. This means that we are able to mount almost four times as many productions as before.

One other notable change we have seen since switching to our new managerial system is the return of staff and artists who had gone over to the film industry at one point. Part of the reason is that the film (and TV) industry itself has become much more competitive. The introduction of our producer system has prompted the return of staff and professionals to the theater scene. And thanks to these changes, you will see that now TV and movie stars are appearing in leading roles in our productions at the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre. - Can you tell us something about the nature of your producer system?

- We have two producers officially employed by the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre and about a dozen who work with us during the course of year in individual productions. An application for funding is made for each project and if approval is given by our evaluations department they come on board for the production. These producers are not necessarily official members of some theater company. There are some free-lance producers too. And, in terms of job security, our two affiliated producers are not permanent employees of the Centre. They are on 3-year contracts only. If one of them is not able to achieve an 80% return on investment for two consecutive years, we also have the option of ending their contract prior to term. And, if we find talented young people we will use them. In fact we are seeing increasingly strong performance by some of the free-lance producers on the scene.

- Would you tell us about the actual organization of the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre?

- The Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre is a large theater company that employs a total of 270 people. Of these, there are about 20 people involved in administrative positions, beginning with myself as director and extending to the middle-management positions. Included among these are the Communist Part officials and labor union officials that are assigned to every government-related arts organization. Supporting me on the artistic side I have an artistic director and on the administrative side I have an assistant managing director, both of whom take general responsibility in their respective areas. We have 150 actors and actresses, 50 people involved in the stage art field and then there are 50 staff working in the areas of building maintenance and cleaning and our cafeteria. Because we are such a large organization, it is not easy to keep our operations in the black. Our administrators all take on several different job responsibilities. Take Nick Yu for example. He is our director in charge of programming and he also serves as chairman of the labor union. And as you know, he is also an active playwright who uses his private time to write. Today, as we are faced with a market economy, we have to take measures like these to keep such a large theater company operable. Our 150 actors and actresses all have contracts with the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre, but they don’t receive any salary when they don’t have a role in one of our productions. Will you tell us about the Centre’s theater?

-

The Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre is located in an 18-story building with an overall floor space of 15,000 m

2

. The building was completed in December of 2000. In the building there are three different theaters, as well as three meeting rooms and two rehearsal studios of 200 m

2

each and a 400 m

2

sports club.

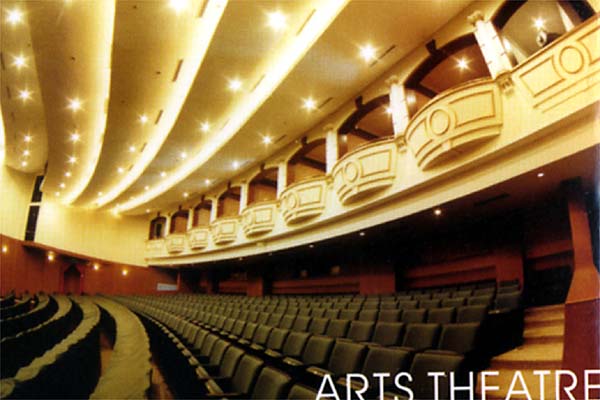

Of the three theaters, the one on the 1st floor of the building is called the Arts Theatre and it has a theatrical type stage with entrance wings hidden from audience view and a seating capacity of 530. On the 3rd floor is a small theater called the “Drama Salon.” It has a floor space of 450 m 2 . In order to accommodate a full range of performances, the space has been finished primarily in black. It has sound-proofed walls on all four sides and the audience seats are movable. Because of this design, the space can be set up for a variety of uses, with an end stage or a central stage and a maximum seating capacity of 288. The third theater is a multipurpose hall called “Studio D6” that is located on the 6th floor. It has a floor space of 500 m 2 . Besides small- and middle-sized performances it is also suitable for conferences. The audience seating is movable and it has a capacity of up to 300. In the building’s lobby there is a bar corner and two semi-open meeting rooms. These are used for exchange with the audience before performances, as a lounge for guests and for smaller scale meetings.

As for the performances given in these three theaters, they are used for about 20 Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre productions a year as I mentioned earlier. Besides these, the theaters are also lent out to about 40 to 50 domestic and international productions annually, either on a rental or full-purchase basis.

In terms of rate of use, the Arts Theatre and the Drama Salon are presently used more than our Studio D6. It seems that this is because everyone is more used to performance formats that have the stage at one end of the hall. Since the Studio D6 is a multipurpose hall there are fewer restrictions on how it can be used. The reason that we created such a space in our facility is because we believe that in the future theater should be used more for communication with the audience and allow audience participation. What is necessary for that kind of theater is not large stage sets but performance spaces that can be used more freely in a variety of ways. We need more of this kind of multipurpose spaces that can be used freely in innovative ways, like the “798” space in Shanghai that makes use of a former factory complex. Since our multipurpose hall is on the 6th floor of our building we named it Studio D6. - How is the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre financed?

-

The average annual budget over the past three years for the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre has been about 32 million yuan (CNY) (approx. 4,090,000 USD). The breakdown is about 30% funding from the government in lieu of support, 30% from ticket sales and 40% from other sources of revenue, including mainly theater rental fees. There is some support from corporations but it is quite small. The reason for this is that the Chinese government’s taxation laws. This is an issue that I am personally applying myself to at the moment. I believe that the U.S. has the most advanced system in terms of tax reductions for non-profit and public service organizations. Over 85% of monies donated are tax exempt in the U.S. system and corporations also gain public recognition for such donations. Under such a system there are plenty of opportunities to get support funding. What is the situation like in Japan? I have heard that this kind of system has not been developed to a large degree in Japan. I believe that Singapore just introduced its tax exemption program a year ago. Unfortunately China doesn’t have many such programs Implemented yet. And, that is why there is very little in the way of donations from corporations. In the rare cases where corporations do provide funding they often demand advertising rights as sponsors. We often refuse these kinds of sponsorship deals when we feel that they will damage the artistic integrity of the production. That is why we can’t depend on sponsorship money from corporations as a significant source of revenue.

For an organization like ours, creating productions of works is our primary purpose and there is no need for us to generate profits. If we make a profit we have to pay tax on it. The taxation rate on profits like these in China is 33%, which is quite high. That is one point I would like to make. I believe that our Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre as it functions now is in fact a form of NPO. We operate in a sort of ambiguous realm where we are not really a corporation, a government agency or a public business group. In reality, I believe we are very close in form to what would be called an NPO in a country with a mature market economy. In such countries and NPO is not taxed, is it? In our case we are taxed at a 33% rate. What’s more, if our cost-reduction efforts cause is to turn a profit that we then pay taxes on, the government is apt to think that we are in a good financial position and therefore feel that it is appropriate to cut our government funding for the next fiscal year. The present policies in this area are definitely detrimental to growth of our activities as business. That is why we are presently arguing our case with officials in the government. This type of lobbying for tax reform can also be considered one of the reform programs that Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre has undertaken since its founding. At the beginning of next year I plan to conduct a fact-finding study concerning the establishment of foreign NPO policies as part of research into a possible proposal for such a policy. If there are any examples that Japan can offer, I would be very interested to hear about them, but I believe most of the advances are being made in Europe now. The U.K., France and Germany all seem to have systems that are functioning quite well and bringing encouraging results. Effective policies are always necessary for any kind of business to develop. - Shanghai is said to have the best developed [theater] market in China and has the largest return rate of production investment, isn’t it?

-

Government investment is larger in Beijing. And because of that, return on investment is lower when seen in comparison with ticket sales. For example, last year the government provided the People’s Arts Theater Beijing with 30 million CNY (approx. 3,830,000 USD). In funding, or about three times more than the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre received. Compared to this, the ticket sales for the People’s Arts Theater Beijing were about 12 million CNY (approx. 1,532,000 USD). Another major theater in Beijing, the National Dramatic Arts Academy, receives between 14 and 15 million CNY (approx. 1,915,000 USD) in government funding, compared to which it recorded ticket sales of about five million CNY (approx. 638,300 USD). At our Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre, on the other hand, our ticket sales are roughly equal to our government funding, both of which are at about nine million CNY (approx. 1,150,000 USD).

The reason that there is more government funding in Beijing is because it is the cultural capital of the country and the main center of cultural exchange. All domestic and foreign productions hope to give performances in Beijing. The purpose of the performances there are to win the acclaim of specialists or government leaders, or to win awards. Selling tickets is not a top priority. Since Beijing is the center of government there is also a custom of sending tickets related officials and a good part of the audience is accustomed to getting their tickets that way. Our situation is completely different in Shanghai. When we gave a performance of one of our productions in 2004, we got no support from the government. If the production fails to break even, we have to make up the difference ourselves, so we tried to sell tickets. And do you know what the people in Beijing told us? They looked surprised and said, “Even if we receive [free] tickets we don’t know if we will actually go to the performance, and you are telling us to buy the tickets?” But, when they heard about the good reviews the production was getting they eventually bought the tickets. Although we did give a bit of a discount for officials who usually get the tickets free. And as a result, we got back almost our total investment of 900,000 CNY (approx. 115,000 USD). The fact that so many invitation tickets are given out for free is proof of the fact that [Beijing] is not a mature market in the cultural event business. I believe that this is a custom that results from a combination of historical factors and practical problems.

In Shanghai, productions are not mounted just for the purpose of winning awards. What is more important for us is the social impact of theater. In other words, the issue for us is whether a play is relevant enough to attract the audience to the theater. At the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre we have built up an audience that is willing to buy tickets to see our productions. And they are not only our audience. The influence has spread to other markets in Shanghai, and now we are beginning to see the fruits of our efforts with the establishment of a solid market. Of course, there are still cases where we send out invitation tickets. But, that number is much smaller than in Beijing. What is the yearly programming like at the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre? -

In compliance with government policy, we draw up 5-year mid-term plans as well as yearly programming. But, now that we live in a market economy, and we have to make adjustments to keep in step with the changing times and conditions. For example, we have been involved with a Japanese theater company since several years ago in a plan to do a joint production, but that plan has had to be shelved because of the inability to secure funding on the Japan side. Also, if a particular production was planned for a 20-performance run but is not drawing a sufficient audience we will cut the number of performances. And, in the opposite case we will extend the performances of a show that is doing especially well. This happens often. Since we have our own theaters we can be more flexible about adjusting plans in this way.

As for the productions performed at our theaters, about 60% of the total have been produced by the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre. The remaining 40% are works by other companies from around China and abroad. As a rule, the productions in our yearly program are evenly divided between original productions by Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre, the famous traditional works and contemporary works from both China and abroad. Since Shanghai has a role as a city of international cultural exchange, I believe that we need to take this fact into account in our programming by including foreign works in our schedule at regular intervals. - How do you engage in projects involving foreign works and foreign companies?

- The first consideration is that it be a meaningful project. Funding is not the biggest issue. The cost of a production is basically shared evenly between the two parties. Each side pays for their own airfare, while the costs accrued during the stay are paid by the host country. From our experience up until now, this type of project where the costs are shared evenly tend to have a high success rate. However, although the intention may be to split the cost evenly, there are of course differences in the cost of living and living standards in the different countries. These differences have to be taken into consideration. For example, the amount spent on meals each day will be less expensive in China than in Japan. And there are also differences in the grades of hotel accommodations in the different countries. Sometime what they call a 5-star hotel in Europe will not seem as good as the hotels in China. So, even if a standard such as providing a room for each person might be the same, the grade of those rooms might be quite different. If both parties can understand these differences there will be not conflict of opinions.

- We see that you are involved in many joint productions with foreign companies.

-

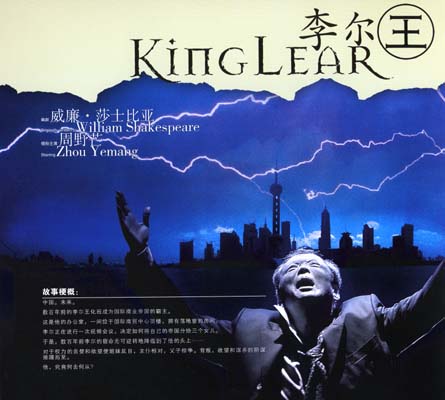

Right now we are working on a production of

King Lear

with the Yellow Earth Theatre of the U.K. The agreement was made last year and we had the premiere in Shanghai at the end of October of this year. Since we have the basic funds, we can decide on these projects by ourselves. And. Although the government approval process takes two or three months, there are no particular problems involved there. We don’t have problems like the Japanese companies that can’t put on a production because the grant doesn’t come through.

One of our primary intentions when we involve ourselves in joint projects is to expose ourselves to different perspectives and cultural orientations that are hard for Chinese to understand if we just continue to create works based on our own Chinese aesthetics and cultural context. Because we don’t really understand the cultural background of other countries, it is very difficult for us to create works that will be accepted and appreciated by foreign audiences. Joint projects with foreign companies give us an opportunity to overcome this problem. Because exchange is a mutual process, joint projects create a situation where everyone involved learns to understand and appreciate the other country’s culture and customs, ways of thinking and forms of expression. And this understanding then is reflected in the work we create. There are times when we get good suggestions from the other side and times when we come up with ideas ourselves that can adapt the forms of expression to something that transcends our inherent differences.

In 2005 we did a joint production with Russia. The original script that we submitted to them was rejected because it was a very long one of about 40,000 characters. So we rethought it and rewrote it until we agreed on a final version that had just a few thousand characters. And, the big cut in dialogue was made up for with music and physical expression, and the final play turned out to be a great success. This is the wonderful potential of joint projects.

Through our experiences in working with overseas companies we have also been able to improve the efficiency our working methods considerably. This can probably be credited to the Western influence. We have become better at getting to the point and working more directly on things. There has also been progress in understanding character and style of foreign arts and the different movements and schools within those artistic traditions. Thanks to this, we have been able to think about and give an even more distinctly Shanghai character to our work than we had before. In addition to understanding others better, it is also important to give importance to our own unique qualities. This is the mission and the responsibility of those who engage in cultural work. - Do you have any plans for any projects with Japanese companies in the near future?

- As I mentioned earlier, we have one project that has been in the works for several years now. We believe that the reason the funding on the Japanese side has not come through for the past few years is the poor state of China-Japan political relations, but [with the new Japanese administration] we are hopeful that the funding will be approved next year. Besides that project there are a few other smaller proposals. I am told that there are proposals that have come from a number of different places, and in his interview earlier, our programming director, Nick Yu, said that it would be helpful if we could be dealing with one source in Japan rather than a number of different institutions. Unlike Japan, Shanghai doesn’t have a large number of arts companies and institutions. So, when we receive a proposal that we feel is not suitable for use, it is normal for us to direct it to one of the other arts institutions around us that it might be more suitable for. In Japan, however, I believe this is not the common practice. Is it because of the intensity of the competition? Among the proposals that have come to us from Japan via various routes, most do not include a cultural exchange aspect. Also, few of the Japanese works that we see proposals are by or for young people. In any genre, there is no future without the activity of young people. I hope that we can see more exchange with young people in the theater field.

Yang Shaolin

Re-established as a stronghold of contemporary theater in Shanghai Creative efforts of the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre

Yang Shaolin

General Manager of the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre

Despite being a public-sector theater company, Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre is also a very profitable theater organization. Its plays that deal with the angst and loneliness of the contemporary urbanites of Shanghai have succeeded in drawing white-color citizens to the theater in recent years and built an important mainstream audience. As a playwright who also serves as the theater’s programming and marketing director, Nick Yu, has played an especially important role in this success. Instrumental in nurturing the young local talent resource, establishing a solid base of profitability for the theater and helping produce works that answer the needs of the Shanghai audience is the Centre’s General Manager, Mr. Yang Shaolin.

Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre

An original work by Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre

www.com

Performed in Japan in 2003 as a joint China-Japan Playwright by Nick Yu, production in the two languages. The work was highly acclaimed for its use of the issue of Internet love to portray the shallow and unstable human relations of contemporary urbanites.

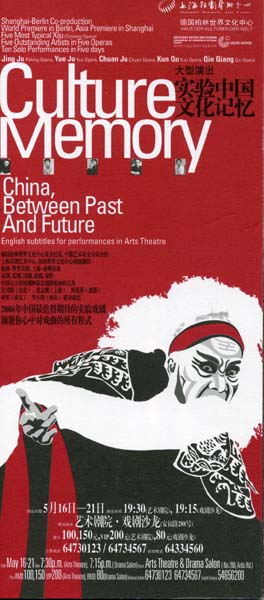

Joint production with the Berlin the House of World Cultures

Experimental productions of five traditional works

Memories of Chinese Culture

Performed in Shanghai in the spring of 2006

Arts Theatre

Drama Salon

Studio D6

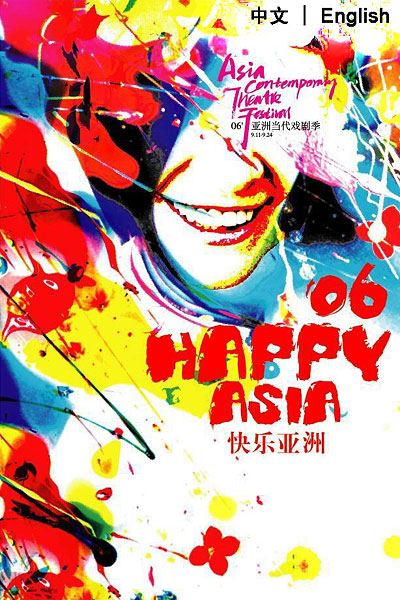

The Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre organizes the Asian Contemporary Theater Festival every September. In 2005, Gekidan Dougeza participated in the Festival from Kobe, Japan.

The joint production with the U.K.’s Yellow Earth Theatre, King Lear

Performed in Shanghai in the autumn of 2006

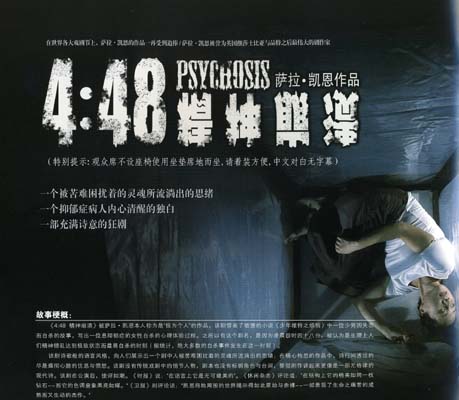

Chinese-language production of the foreign contemporary play 4.48 Psychosis

Performed in Shanghai in the autumn of 2006

Related Tags