- We would like to know a little about SESC’s orientation towards arts and culture.

-

SESC is not a cultural or sports institution. It is a social welfare institution, which uses every possible strategy to promote the people’s development and quality of life. The organization was created back in 1946, when a group of entrepreneurs said to the Brazilian government: “We want to create a social welfare institution for our workers and the general public. We need a law that will oblige the companies to pay [a contribution].” The latter half of the 1940s right after the WWII was a very special period that brought democratization and urbanization to the country. Brazil was leaving a rural model in favor of an industrial one. There was the need for a better qualified labor force to support the economic transformation that Brazil was to go through. It was necessary to have a better professional training and welfare projects so that the workers would feel happy and so that there would be greater social stability. At that point the Communist Party was strong, supported by the Soviet Union. There was a possibility of Brazil adopting a model similar to the socialist one and the military, the business elite and traditional families were concerned about this. That is how the idea of professional training appeared, along with the idea of social welfare. SESC and SESI (Social Service of Industry) were created at this time, under the protection of confederations of industry and commerce. But we are not an employer’s institution. We, SESC’s staff members, are employed to carry out programs that do not necessarily have a binding with employer entities from the conceptual or ideological point of view.

In the field of welfare projects, there are many areas where action is needed, including education and health, as well as leisure and culture. Sport is one of the activities that comes first, but culture is also an important and catalyzing element, of involvement and vitalization of people’s actions. - Do you think that today SESC has its biggest presence in sports and culture?

- We have more presence in culture. Sports today are clearly divided between professional sports and sports as a tool for education and change. We are strong in what we call “sports for all,” the inclusive sports programs. But, this does not get attention often in the media. For example if 300 companies come together to promote a sporting event, there will be only a small note in the local newspaper. Now, to point out the difference, we bring, through the Japan Foundation, video showing the work of Kazuo Ohno at SESC Consolacao [a SESC facility in Sao Paulo]. It was on the front page of ‘Ilustrada’ [culture section of an important newspaper]. You can see the difference. Different from the sports, in Brazil non-professional “underground” or avant-garde cultural activities get the same amount of media attention as commercial culture. What Japan Foundation, as well as other international institutions, brings is something extraordinary to us. Why? First, the Japanese presence in Brazil is an important fact culturally, economically and politically, especially in Sao Paulo. Second, the Japan Foundation is not interested in bringing Japanese culture because it is good business. And when it needs partners in Brazil for an event, who does the Foundation talk to? It talks to SESC.

- What are the criteria SESC uses to select events?

- Public interest; its reach. We did an exhibition of Japanese toys about 10 years ago, a beautiful one. They came from a museum in Kobe. Who would you think would be interested in Japanese traditional toys in Brazil? But, this exhibit was a huge success here. It went to Curitiba [capital of the State of Parana], to Rio de Janeiro and, if we had the opportunity, we would have taken them to other places. It was fantastic.

- Why, in your opinion, was it such a success?

-

It was popular for its quality, its beauty and the information that was contained in it. I will give you an example. What caught my attention was a little toy that appears in many different cultures. It was a chicken with little chicks around it, made of papier mach? or clay. Such figures are common among Brazilian Indians, Japanese, and there are examples in Russia, in Africa, among people who do not have contact with each other. It is the collective unconscious: we all come from the same place. I also visited the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka, one of the most important in the world. The director of the museum, Professor Hirochika Nakamaki, had a great interest in Brazilian Indians. First, because the Indians have roots in the East, more than we do. Second, because, nowadays, to bring cultures together, it is more and more necessary to search for the essences, to find what kind of primordial element is there. In that area the Indians are strong, and that is why he, as a Japanese, has interest in them. This proximity helps to define the necessity of going a bit beyond, into the essence, and to avoid elements with business values. When I mention business, it is not that I am against those who make business. It is just that we at SESC do not engage in activities for business profit.

We would like to know about Mr. Ricardo Fernandes, who was the coordinator for the performing arts at SESC for 14 years and who today works as an independent producer. How is the coordination of this section done today?

- Since he went independent, Ricardo has done some works and brought some proposals for presentations to SESC that always have a very contemporary characteristic. He is like a contemporary curator for SESC. I wouldn’t say that he is a curator only of drama, like before, but also of dance and visual arts, because nowadays all of that is mixed. And Ricardo understands the moment so well. He knows very well what SESC’s aims are, too, because he worked with us for a long time. He has now brought a group from Japan, the Gekidan Kaitaisha. He is also organizing part of Brazil’s presentation for the World Cup in Germany in June. Actually, the two countries with whom he has had a stronger relationship are Japan and Germany. I would say that he is not a good curator for a traditional show. He has difficulties in understanding and involving himself with the business establishment and such. He is a man of the contemporary, and of the newest kind, too.

- Do you have your own staff in charge of everything?

- SESC has always concerned itself with the training of its human resources. Everyone has the opportunity for taking courses and going abroad to study. I was one of the first ones. In the 1970s I went to Switzerland, to study management at the Swiss Graduate School of Public Administration (Idheap) in Lausanne. After that, many others also went abroad, to obtain a deeper knowledge in the areas of management, leisure and culture in general. We are aware of the need to value our staff members and cultivating their abilities, to make them more capable of developing their work. There is a concept in Brazil that in the social and cultural areas it is enough to have good will. That is a mistake. It is necessary to have professionals who understand about management and planning. SESC has long adopted this kind of professional perspective. These people end up growing within the institution and taking up new positions. I think we need to have this kind of program, but we also have to respect those who come from outside and help us with a new way of looking at things. Valuing the human resources in SESC is an ideal that is not only talked about, but practiced as much as possible.

- What is the relationship between SESC and the drama director Mr. Antunes Filho?

- In the beginning of the 80s, Antunes already had directed many things in television and theater, but his dream was to have a project to train actors, directors, lighting technicians; that is professionals of the theater. He convinced SESC to create a project of drama research within the institution, in 1982. Antunes was always a rigorous man. I call him the ascetic of the theater. He is not the only one. Antunes is a disciplined and severe person, but one of a fantastic efficacy and great creativity. He is truly one of the great, if not the greatest, drama director in this country. Within SESC, as part of the staff, he began to carry out the job of training actors and directors. Many famous people in Brazilian theater and TV have been trained by him. He has also trained lighting technicians, set and costume designers. More recently he is working with a group of playwrights, too. SESC provided him with the means to do his work and also with the infrastructure, such as workshops for creating graphic materials, set designing, costumes. Antunes can also be credited with being the first in Brazil to discover Kazuo Ohno. He helped in this, together with the Japan Foundation and the family of the late Mr. Takao Kusuno [a butoh dancer who emigrated to Brazil in the latter half of the 1970s and brought new inspiration to the Brazilian dance scene]. Kazuo is a revolutionary figure who had an impact on many audiences around the world. He is an important person for us in SESC.

- Do the performing arts programs of SESC always have something of a multicultural character?

- Always. One of our strategies is multiculturalism, the variety of tendencies, the respect for divergence. This means that we always give space to the traditional, but also to the revolutionary. There is a very delicate concept, which is transgression. There is no growth and development of culture without transgression. When Picasso draws the face of a woman, fragmenting it into three different dimensions and showing them all at once on the same painting, he is innovating. That is the kind of transgression I am talking about. And there is a vast field for this, in all of the visual and performing arts. So this multiculturalism, this variety of proposals, is respectful. What I mean is that the very base of welfare projects has to do with giving value to the human being, who deserves respect within a standard of absolute equality. This is not a matter of religion or politics. It is about culture. From a cultural point of view, we are all fundamentally equal.

- In this sense, are the Brazilians more prepared for multiculturalism?

- In a way, yes. It is one of our values. The great national identity is this multiplicity of values that we have. This was said to me by the director of the museum in Osaka. He said an interesting thing. He said, “Look, Brazil is a great multicultural nation that is growing and developing to have an important role in history.” He said that the other great multicultural society was the American one, which, in his opinion, is now facing a time of decadence. I cannot go deeper into this now, but he talked about the difficulty of different cultures relating to each other there, about the slums. In Brazil, we have lots of social and economic problems, but this one is smaller.

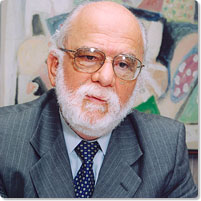

Danilo Santos de Miranda

What is SESC, the Brazilian organizations that runs comprehensive culture and arts facilities in Brazil

Danilo Santos de Miranda

SESC Sao Paulo regional director

Founded in 1964 by the Brazilian commerce and services entrepreneurs, SESC (Social Service of Commerce) is a social institution with strong presence in the areas of culture, sports, health and education. music, drama, dance, courses for the elderly and sport activities for adults and children are offered to the public, as well as programs for environmental awareness and social inclusion. There is a SESC regional administration in every State and the Federal District. SESC Sao Paulo has the largest budget among these and administers 30 facilities (units) in the capital city of Sao Paulo and other towns across the state, which together offer programs attended by more than 300,000 people per week.

Among its activities, SESC boasts outstanding achievements in the performing arts, both quantitatively and qualitatively. In 2005, Sao Paulo SESC organized 4,500 domestic and foreign stage performances.

SESC (Social Service of Commerce)

SESC is a private institution established in 1946 to help carry out social welfare programs aimed at raising the level of cultural activities to benefit the Brazilian people. It is funded mainly by Brazilian commerce and service corporations through a mandatory tax established by the 9,853 law (13 of December, 1946). Every company pays this tax according to the amount of salary paid to its employees. The institution also receives donations and uses revenue that comes from paid activities in its units. SESC Sao Paulo has the highest revenue, with an annual budget of 400 million Reals (approximately US$ 187 millions), which is 40% of the national total. Twenty percent of what Sao Paulo obtains is redistributed nationally. The budget of each unit varies according to its needs. The activities schedule is composed of those locally organized and those coordinated regionally and nationally. In addition to organizing and supporting a large number of international performing arts festivals nationwide, it also supports the creation of new works. In recent years it has also focused efforts on collaborative projects between domestic and foreign arts companies. SESC also cooperates in helping Brazilian companies participate in overseas arts festivals. The Japan Foundation has engaged in many activities in partnership with SESC in the last twenty years. Some of the main events have included performances by Suzuki Tadashi’s SCOT, Takigi-Noh, Banyu Inryoku, Dumb Type, Pappa Tarahumara, Rinken Band, Ishinha and many others.

SESC Sao Paulo

has 30 comprehensive culture facilities in Sao Paulo State (eight in the capital city of Sao Paulo). These facilities each have their own distinct character and conduct activities from a budget allotted according to its size. Among these, the SESC Consolacao in Sao Paulo city where Antunes Filhou serves as artistic director is especially important in the performing arts field. Under Filhou’s direction, the theater activities conducted here are run under a directorship system. The other SESC culture facilities conduct programs independently as well as receiving programs planned at SESC headquarters. Other internationally known facilities include the culture center in Sao Jose do Rio Preto, which independently organizes its own international theater festival, and the SESC Santos where an international dance festival is held (being attended this time by Ishinha from Japan).

As an affiliated enterprise, SESC Sao Paulo also runs the Centro de Pesquisa Teatral, which gathers dramaturgy from around Brazil. SESC Consolacao opened the Centro Experimantal de Musica in 1984 as an experimental program that uses a unique methodology to create interaction with the community through music. Also, in 1994 SESC began publishing the periodical REVISTA E . Active information dissemination and publicity efforts are also conducted thhrough the organization’s SESC ONLINE (

www.sescsp.org.br

) website.

In 2005, the number of SESC events related to performing arts within Sao Paulo State alone was as follows (number of audience in brackets):

. Plays: 3,968 (807,000 people)

. Music concerts: 405 (2,150,000 people)

. Dance: 656 (310,000 people)

D F Malan Street, Foreshore

Cape Town, 8001

tel: +27 (0) 21-410-9800

fax: +27 (0) 21-421-5448

Antunes Filho’s newest work

Antigone

Photo: Nilton Silva

Drama director Antunes Filho and actresses of CPT Theater Study Center

Photo: Evelyn Ruman

Related Tags