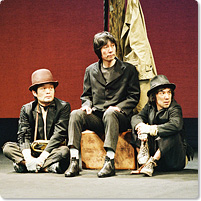

“Kiyama Theater Productions” production

Yattekita Godot

(Godot Has Come)

Written by Minoru BetsuyakuDirected by Toshifumi Sueki

(Mar. 24-31, 2007 at Haiyuza Theater) Photo: Teruo Tsuruta

Data

:

Premiere: 2007

Length: 1 hr. 40 min.

Acts, scenes: One act, 2 scenes

Cast: 10 (6 man, 4 woman)