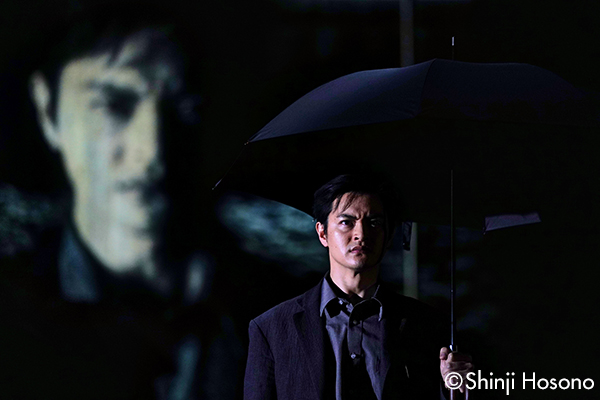

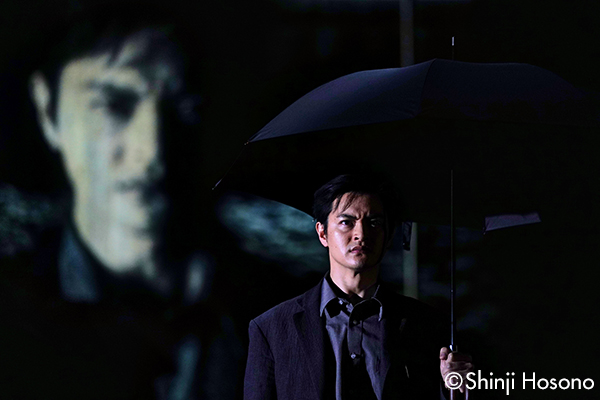

Even If There Are People Who Laugh at Her (Kanojo wo Warau Hito ga Itemo)

(Dec. 4 – 18, 2021 at Setagaya Public Theatre)

Photo: Shinji Hosono

Seeking out the voices of the person’s concerned, Misaki Setoyama’s unwavering capacity to listen

Photo: Takayasu Hattori

Born in Tokyo in 1977, Setoyama graduated from the Waseda University’s School of Political Science and Economics. In 2001, she started the theater company Minamoza, for which she would be the playwright and director. Among her representative plays are Emotional Labor, Mienai Kumo(Invisible Cloud) (original by Gudrun Pausewang), Yubi (Fingers), Familia, and others. In 2016, Setoyama’s play Karera no teki (Their Enemies) won the 23rd Yomiuri Theater Award for Excellent Work. In 2019, Setoyama won the 26th Yomiuri Theater Awards Excellent Director award for her direction of the Office Cottone production of Yoru, Naku, Tori (Birds that Sing at Night) and the Ryuzanji Company production of Watashi, to Senso (Me, and the War). Other representative works include the Office Cottone production of Rachi mo naku Kegare naku (playwright, director), Oreste and Purades (playwright) at Kanagawa Arts Theatre, Djihad at Saitama Next Theater and Ano Dekigoto (The Event) at New National Theatre (directing both). Setoyama has also written the screenplays for Amizu Haruko ha yukuefumei (Japanese Girls Never Die) and River’s Edge Her play THE NETHER won the 27th Yomiuri Theater Award for Excellent Work and Best Director.

In 2020, received the 70th New Face Award of the Minister of Education Award for Fine Arts. Setoyama also won the 28th Yomiuri Theater Awards Excellent Director award for her direction of The Contemporary Noh plays / Eudemonics inspired by Noh plays Dojoji and Sumidagawa.

Minamoza

Even If There Are People Who Laugh at Her (Kanojo wo Warau Hito ga Itemo)

(Dec. 4 – 18, 2021 at Setagaya Public Theatre)

Photo: Shinji Hosono

Theater company Minamoza Karera no Teki (Their Enemy)

(Jul. 24 – Aug. 4, 2013 at Komaba Agora Theater)

Takayasu Hattori

*1 Kohei Tsuka (1948-2010)

Tsuka is a playwright, director and novelist. He began his theater career while a student at Keio University, and in 1973 he wrote The Atami Murder Case (a perverse tragicomedy in which chief detective, Denbei Kimura, repeatedly role-plays with a useless detective, Rukichi Kumada and others, the circumstances that led the murderer Kintaro Oyama, who was caught killing his lover Hanako, into a “first-class criminal”) for which he became the youngest person at the time to win the Kishida Drama Award, at the age of 25. In 1974, he established the Tsuka Kohei Office, which went on to create a sensation in the 1970s and ‘80s. Taking a single play, Tsuka would freely manipulate the stage script by his Kuchi-date method of having the actors improvise changes in the lines he gave them by word of mouth in order to repeatedly create new revised versions of the original play scripts he wrote. In the process, he had a great influence on many playwrights, directors and actors.

*2 Parasyte

Humans whose brains have been taken over by parasitic creatures (parasites) that have flown in from space have come to prey on other humans. Shinichi Izumi, a high school student, is attacked by a parasite, but the parasite is only able to take over part of his right hand instead of his brain. This highly popular manga depicts the strange symbiotic life of Shinichi and the parasitic creatures who have come to call themselves “Migi” and the ensuing battle between humans and the parasites.

*3 Kita-ku Tsuka Kohei Theater Company

Kita-ku Tsuka Kohei Theater Company is a theater company based in Kita-ku, established by Tsuka in 1994 at the request of Tokyo’s Kita-ku (Kita Ward). They focused on training actors but disbanded in 2011 due to Tsuka’s death.

*4 The TEPCO OL (female office worker) murder case

An unsolved case of a murder that actually occurred in 1997. The body of a murdered woman who worked at the Tokyo head office of Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) was found in a vacant room of an apartment building in Maruyama-cho, Shibuya Ward. It attracted attention as a case in which a female employee of a large company during the day was engaging in prostitution at night, and an illegally residing foreign man who was falsely accused of her murder. The incident became the subject of numerous non-fiction books.

*5 Michiko Kanba

A female student activist at the University of Tokyo who participated in the protests against amendments to the Japan-U.S. security treaty. She was killed in a clash with police at a demonstration site on June 15, 1960, at the age of 22.

*6 EPAD

This is one of the support projects implemented by the Agency for Cultural Affairs together with the “Emergency Performing Arts Network,” which was launched in 2020 with the participation of industry organizations to support the performing arts industry, in light of the devastating impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on the industry.

Related Tags