Hottamaru-biyori (Hottamaru Days) (2015)

(C) NaoYoshigai

Dancing and filming pre-verbal emotive impulses

Photo: Natsuki Kuroda

Nao Yoshigai (b. 1987 in Yamaguchi Prefecture) is a choreographer, dancer and filmmaker. After studying dance in Japan Women’s College of Physical Education’s Department of Dance, she went on to study at the Graduate School of Film and New Media of Tokyo University of The Arts. Yoshigai began activities as an artist in the 2010s. Since then her works combining physical expression and filming as essential elements have won high acclaim internationally, as exemplified by the selection in 2019 of her film Grand Banquet (2018) for the Director’s Fortnight Short Films category of the 72nd Cannes Film Festival. Yoshigai was born and raised in what is known in Japan as the “lost 20 years” after the bursting of the country’s “Bubble Economy,” a turning point in the country’s postwar economic history that occurred in 1990.

Hottamaru-biyori (Hottamaru Days) (2015)

(C) NaoYoshigai

Hottamaru-biyori (Hottamaru Days) (2015)

Directer: Nao Yoshigai

Performer: Risa Oda, Satoko Shibata, Yu Goto, Kaho Kogure, Ayaka Suga, Yui Yabuki

(C) NaoYoshigai

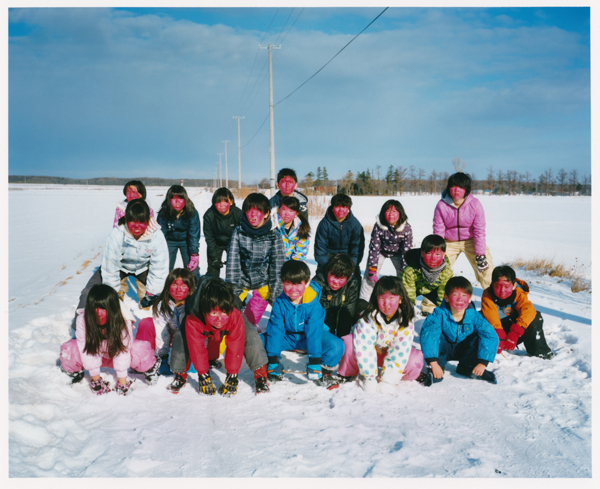

Shari (2021)

The photographer Naoki Ishikawa discovered the appeal of the Shiretoko peninsula, and in order to explore and communicated this appeal with the local photography lovers and the town of Shari (Shari-cho) started the “Photography Ground Zero Shiretoko” movement and made this film with Nao Yoshigai as director. From 2019, research began on the natural environment, and life in Shari and people who live there. In the film, Yoshigai takes the guise of an “Akai-yatsu” (Red thing) that exists between the people and the wild animals (or “beasts” as she calls them) and narrates the film herself as she roams around Shari, interweaving the wild landscape and the sounds it emits into a collage work that is part documentary, part fiction.

Director: Nao Yoshigai

Photographer: Naoki Ishikawa

Assistant director: Naoki Watanabe

Music: Kazuya Matsumoto, Acoustics: Masaya Kitada

Appearances by the people of Sharicho, the surrounding sea, mountains, ice and “Akai yatsu” (the narrator Yoshigai)

(C) NaoYoshigai

Photo: Naoki Ishikawa

Grand Bouquet (2018)

Written and Directed by Nao Yoshigai

Cast: Hanna Chan

(C) NaoYoshigai

Related Tags