- Ainu culture has been receiving renewed attention since UPOPOY: National Ainu Museum and Park (*4) opened. OKI-san, you’ve been active as a musician since long before that opening and have been introduced by many titles: a tonkori musician, a descendant and contemporary artist of Ainu culture, an innovator of world music, and an Indigenous musician and a music producer, to name a few. To begin with, could you tell us what kind of artist you are, in your own words?

- Every musician needs something unique to them. For example, if you’re making R&B music, you’d follow its conventions. It’s not as if you have to be a black person to make R&B, but it begs the question of who, where and in what era you’re in when you engage in R&B. In that moment, it’s important to have your own personality, something that no one else has. In my case, that “something” is tonkori, which plays a central role in my music-making. At the same time, it is also important to have a sense of “Ainu-ness” within myself. Building knowledge and having musical training is one thing, but besides that, it’s necessary to have a fire burning in your heart. I think things fall apart when that fire is about to go out.

As an artist, I think about what kind of people I meet and where I choose to be and, even if I lack confidence, buckle down and give it a shot. Also, I think it’s best not to believe you’re making music for your own sake. Of course, the music is also ultimately for yourself, and that in itself is important, but what about the people who listen to your music? There are times when unexpected people listen to my music, not just “fans”. For instance, I was hospitalized until just the other day, but the nonchalant doctor looking after me one day said, “Actually, I’m a fan.” My body was weak, but that comment filled me with a quiet happiness for the fact I make music. Even though I might feel satisfied right after making a song, after some time, I become fixed on how I can make it better. I also feel the same way with live performances: sometimes I think it went well, other times I don’t. If you’re too self-concerned, your self-esteem won’t be very high. However, I find comfort in the idea that the one judging is not myself, but those who listen to my music. - Because of your music career, the tonkori has become a world-famous instrument despite it being almost unheard of until around the 1990s. You’ve put out a really wide range of music, from cutting-edge music to performances of traditional pieces that almost stoically stick to classical styles, and collaborations with artists from abroad. Where did the wide scope of your originality come from?

- I’m not only looking at the Ainu people; I also have many Indigenous acquaintances. For example, I visited the National Gallery of Australia in 1996. When I used to think of museums in Japan, I pictured researchers wandering around with the Ainu people under their stewardship. But I didn’t feel that way in Australia. The lead curator of the exhibition of contemporary Indigenous Australian artists being held at the time was Djon Mundine of the Bandjalung people (Aboriginal Australians) who had dreadlocks down to his feet. Djon Mundine handed acrylic paint to his people and asked them to create paintings on canvas that, until then, had been painted on materials like tree bark. He then exhibited these canvas works in Europe. By handing his people acrylic paint, their work flowed into the art world. I think this is also a role of a producer. Also, in places like the USA, Indigenous people themselves work as producers. And at the UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations that I visited in 1998, the Indigenous people of Australia I met were lawyers in international law.

Having seen many different examples like these, I doubt things will improve if we keep to simply introducing Ainu culture. I might have more sway if I were a lawyer, but as a musician my role might not vary much from being asked by tourists and politicians to give a song and dance. But nothing will change by passively responding to such requests. Instead, I feel the need to create a platform by myself and take charge as a producer. I used to think that art and expression were about digging deep into myself. Things are different to me now, and what I find important is how one relates to society. I think the role of art is societal. - You enrolled in Tokyo University of the Arts. Were you already envisioning making a living through your own art back then?

- I couldn’t picture anything else. The reason I aimed for an arts university to begin with was because of the influence of my father, a printmaker. I actually rather disliked art, since I felt like I couldn’t surpass my father. When I was preparing for the entrance exams, I got to work sketching the one plaster figure we had at home while blasting out music by the Steve Miller Band. My father, who was a stoic person, said, “Drawings should be done in silence.” He was the kind of person who’d say something Leonardo da Vinci might say. That’s why I decided to follow my own path. The truth was I wanted to be a musician from the start, but I’d given up because of my parents’ strong opposition.

But one day, my father gave me a translated version of the book Ishi in Two Worlds: A Biography of the Last Wild Indian in North America by Theodora Kroeber. This was the only time my father ever told me to read a book. Moved, I bought a collection of poems by American Indians (*5) and began reading them. From there, I hunted down other books like Lévi-Strauss’s Tristes Tropiques and his theory of structuralism, and philosophical books by Gaston Bachelard. At the time, a lot of those books were available in a bookstore in the upper floors of an Ikebukuro department store that also had a gallery, where I could stop by and see artwork by artists like Jasper Johns.

I aimed for an arts university not because I wanted to become an artist, but because I had a vague notion that if I couldn’t be a musician, I’d like to try design. When I got rejected after high school graduation, I was filled with regret and a fire was lit in me. I ended up trying for two years before being accepted by Tokyo University of the Arts, but I think I was just lucky that the entrance exam involved a plaster figure in a good location with good light, making it easy to draw. Once I got in, it was funny to see that the other students weren’t the most brilliant. Even the professors would joke that our class wasn’t the most talented. - After all that, you entered the Department of Crafts. What was it like there?

- I went with a major in metal forging because it was the major with the strongest connection with contemporary art at the time. It sure was interesting, but after I enrolled, it was the ancient art that drew my attention. I learned a lot about Buddhist figures, architecture and painting from the Muromachi period. I had a really good feeling when learning about these things hands-on. This was a formative period for my sense of self as a Japanese person. On the other hand, while I was interested in Japan, I became obsessed with reggae because of my interest in American Indian culture. One day, the one book that my father recommended to me became an ironic trigger, and I found out by coincidence that I have a biological father in Hokkaido who is Ainu, meaning I have Ainu roots.

So, off I went to snowy Hokkaido. It was great at first. Family I had never met before gave me a warm welcome. It was a happy time, but as I returned to Hokkaido several times and met various people, I came to realize absolutely nothing about myself felt very “Ainu”. One day, when I was staying in Hokkaido, my father stopped by the cabin I was renting and told me I should come see the bar his brother was running, so we hitchhiked together to Lake Akan. Opening the bar door, there was a counter where others were sitting in a row, waiting for my father to arrive. I felt the stares of these Ainu men sitting in a row, as if it were a scene from a western movie when a drifter gunman enters a saloon. After drinking so much I couldn’t remember what happened in the end, we woke up the next day and drank again, and when it was time to go home, a friend and relative of my father offered a ride. I was in the front passenger seat and my father was passed out drunk in the back seat.

While driving through the virgin forest of Lake Akan, my friend in the driver’s seat said to me something along the lines of: “How on earth could a fancy city boy like you who grew up in Tokyo understand about the Ainu at all?” Listening to him talk, I looked out at the vast forest that filled my window and suddenly, it hit me that not a single tree belonged to the Ainu. Until the previous day, I’d been hearing men brag about past adventures and misadventures and had learned the Ainu word samo.(*6) I was still hearing such talk from the seat next to me, yet not a single tree belonged to the Ainu. The thought brought a tear to my eye. For the first time in my life, I was thinking about Indigenous land rights. I might have given the issue deeper thought if I had known more, but at the time, I could only wonder sadly why this wasn’t the land of the Ainu anymore. The words I heard at that time had a big impact on me. Until then, I thought I was being welcomed, but even if I was, it would be as an outsider’s welcome. I felt that no matter how I awkwardly attempted to conduct myself, I would be different…. - After graduating, you headed for New York.

- I kept visiting Hokkaido for about a year, but after a while I stopped. I thought I’d had enough, but my heart didn’t seem to agree. When I returned to my university, various things began to feel hollow. Things I’d always liked began to look faded. For example, I suddenly lost interest in the books or ancient things that I used to enjoy. I learned I was Ainu and thought I would be welcomed by other Ainu people, but when I realized that wasn’t always the case, I returned to my life in Tokyo, only to learn I couldn’t go back to the way things were. That was the hardest part. I used to think my parents and I were ethnically Japanese (wajin), and when that idea got shaken to its core, I assumed things would change, only to find myself at the beginning again. I felt as if I were being hurdled back and forth, and I just felt empty. It was painful in many ways, and I wasted a lot of time in that uncertain mindset. It was time for me to finish up university, so I saved up some money as a welder and went to New York.

I went to New York with the hope I wouldn’t need to think about my issues with my Ainu identity, but this time I had to confront the annoying fact that my own unconscious behaviors would be perceived as “Japanese”. I blamed all sorts of things on the United States at first, but in the midst of making a life for myself over there, I adapted. I think I was trying to break away from something. I was fed up with concepts of Japan and Ainu, but even though I wanted to escape, I realized I was mostly making Indigenous friends in New York. I started going to American Indian poetry reading events after finding a flyer posted on a telephone pole in the city. That’s how I met Joella Ashike, an artist from the Navajo Nation, at a SoHo gallery. While we were talking, I asked if I could pay a visit to her home in Arizona. She said sure and gave me her address. I took the polite exchange seriously and went to Arizona. After hitchhiking, I finally arrived at the Navajo reservation and found her home at the foot of the sacred Big Mountain. It was an arid zone with no water or electricity, and no other homes for about 10 km. I couldn’t have imagined such a place in a developed country like the United States. - You mentioned this story about visiting the Navajo reservation when you were interviewed by the artist Mayunkiki at her solo exhibition in Sapporo.(*7)

- That’s right. My friends at the time went to Asia and India, but I didn’t go because I didn’t want to follow the crowd. Encountering American Indian culture had brought shocking experiences for me. Living in Japan, I’m used to seeing the mountains covered in a green and garden-like landscape. But Arizona was arid and cloudless with exposed, bare land and rock, giving me the visceral realization that I live on the planet Earth.

As I walked through that arid land at night, the Milky Way poured over me like a dome. Scenery you might find in one of the Indigenous poetry books I used to read spread out before me as a coyote howled. Here, the day would start with a ritual, burning sage on an abalone shell while listening to the words of prayer and the sound of drums over the radio. If my hosts invited me to go out to use the shower, they meant hijacking the shower used by employees at a hostile company at Black Mesa that mines coal from their sacred mountain. While resistance activities against government land expropriation and rituals like the Sun Dance were common, like anywhere else, there were young people that would go shoot rifles in the desert, smoke weed and get up to no good.

Then one day, when I was nearing the summit of Big Mountain with a young troublemaker and self-proclaimed cameraman, he told me to wait and go no further. When I asked why, he said he didn’t want others to see him praying. When that friend suddenly went from hanging out to being serious, I felt as if I could see the deep roots underneath who he was. That’s when I sensed I’d one day return to Hokkaido and face my own roots.

I stayed there for about a month, but I had to return to New York because my rent was due, and my money was running low. Looking back now, I think I should have stayed longer or visited more times. At the time, I was somehow satisfied. Maybe the discomfort I felt in relation to being Ainu and such had washed away. Instead, I took interest in things like the Caucasian culture in New York. - I heard that the reason you returned to Japan was to do filmmaking.

- Before deciding to return to Japan, I was planning to move to Hollywood and get involved in special effects. But then, I got an offer to work for a Japanese-American TV drama, so I quit my job and returned to Japan. However, it became more and more difficult to get in touch with the producer until I finally found out the project was cancelled. What followed was a very difficult time in my life. I started a part-time job at a Japanese studio that makes Godzilla costumes, but compared to the facilities in New York, I felt defeated working in that cheap, prefab building. Feeling that I needed to take matters into my own hands instead of working for someone else, I got it into my head that a documentary was doable alone. That’s when I paid a visit to Kayano Shigeru (*8) in Hokkaido.

When I told him about how I arrived there, Kayano-san told me that “an Ainu is an Ainu, no matter where or how far they go.” When we talked about documentaries, he said, “Why don’t you film me?” Thinking about it now, if I had filmed him at that time, it would have been the first documentary made by an Ainu person about an Ainu person. I regret not doing it now, but I was hesitant at the time. In the end, I didn’t film Kayano-san and instead went to see my relative, Kawamura Kenichi.(*9) Back then, Kenichi-san had visitors almost every day and he would often throw rowdy get-togethers. One day, a drunk Kenichi-san went to another room and tossed me a tonkori. It was my first time holding one. It has a quiet sound, with only five strings and no frets, so all you do is pluck it. Kenichi-san told me “We could use an Ainu person or two putting music out there”, so I took the tonkori home with me. - So, that was your first time getting your hands on a tonkori.

- Right. At the time, I had a multi-track recorder (MTR) that could record 4-track cassettes, and a rhythm machine, both given to me by an acquaintance since I was so into music. After returning from Hokkaido, I started recording tonkori with it. Then I added base and started flipping through my books with the idea of adding Ainu words. After making 3 or 4 songs, I felt I had a knack for it. It was an unfounded sense of achievement I never had when I was drawing. Looking back, I might have just misunderstood my smug sense of satisfaction as a talent, but this was the final turning point for me. That’s when I decided to base myself in Hokkaido.

- In a previous interview, you mentioned that as soon as you moved to Hokkaido, you went to see Kuzuno Tatsujiro,(*10) who is respected as an elder knowledgeable in Ainu language and culture. You said you learned a lot while living in a small house on his grounds. How did you meet him?

- I read Kuzuno-san’s book, called Kimusupo, that I bought from the Shakshain Memorial Museum in Shizunai (Shinhidaka Town), and was just determined to speak with him in person. Ainu literature at the time was filled with too much folklore to be relatable to me. But in Kimusupo, Kuzuno-san wrote in the Ainu language about topical things, like how nuclear power sullies the earth. It was wonderful to see someone writing about contemporary, societal topics instead of traditional tales. It broke the stereotype of an old person telling old stories and reminded me of the spiritual elder who was a member of the hip-hop group Arrested Development. I asked to live on his grounds, where he taught me the Ainu language, the contents of Kimusupo, and we wrote songs together. I remember this experience very fondly.

- As a result of that experience, your debut album Kamuy Kor Nupurpe (1996) was born.

- That first album was from a very pure time in my career. When I listen to it now, I pick up some problems with the sound, but even so, first albums are always something special. I struggled and struggled to get to that point. But it’s possible I enjoy the struggle and mess. In any case, I experimented with a lot of things. Until March 2011, I released an album almost every year for 15 years. The 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake was the biggest shock of my life. Three nuclear power plants were in ruins, in Japan at that. After that disaster, I lost the will to make music for a while. It was the biggest mental shock, and I’m still kind of carrying it with me.

- After Ando Umeko co-featured on your second album, you produced both her solo album IHUNKE (2001), which has since drawn significant attention and has been called a “masterpiece”, and her following album UPOPO SANKE (2003). How did you two meet in the first place?

- At that time, traditional Ainu musicians wouldn’t do something like release their music on CD under their own names. On top of that, it was the first time an Ainu person was producing such music. This was also a calculated strategy. I told Umeko-san, “Let’s make some money with this.” We didn’t discuss noble things like conveying Ainu culture or telling messages. That’s how we started producing our albums.

I met Umeko-san in 1997 when making my second album Hankapuy (1999). People from a number of Ainu culture preservation societies came together at an Ainu cultural festival, where I was watching performances on stage. That’s where I saw a group from Obihiro (Hokkaido), led by Ueno Sada and followed by Ando Umeko on vocals. I thought she was fantastic. When I reached out to her, I found out she already had a CD that came out in 1995 called Mukkur and Ando Umeko (produced by the Makubetsu-cho Board of Education). It sounded like it was recorded outdoors, with the trickling of a stream running through the whole CD, and it included four upopo acapella bonus tracks. It was so good I thought it was incomparable. I asked her to join me at a live performance in Obihiro, and with the urge to record her, I had her join in on my album. - MAREWREW, a vocal group that you also produce, was credited for the first time on your third album No One’s Land (2002) and have since released four of their own albums: MAREWREW (2010), Mottoite, Hissorine (2012), cikapuni (2016), and mikemike nociw (2019). How did MAREWREW form and how did the decision to produce them as their own group come about?

- The person I was dating at the time was an Ainu woman from Asahikawa who had a wonderful voice for traditional songs. We began making songs and playing live together, at which point other vocal members naturally came together and became a group. So, we needed a group name, and landed on MAREWREW. Other than the Preservation Society, there weren’t any groups singing Ainu songs, so we decided to be the first. Nowadays many people are involved in Ainu music, but at that time I was the first tonkori player active in the music industry—we could have had many Guinness records. I run Chikar Studio as a music label, so I also have exchanges with people in the music industry overseas and have worked with Oshiro Misako for Kita to Minami (2012) and Asazaki Inue for Amamiaynu (2019). I might enjoy producing for others more than for myself, actually. In the end, I married that girlfriend, and we have two children.

- Your latest single was released online. Do you have plans for your next album?

- People don’t put out albums in this day and age anymore. It’s no longer a necessary goal to create music in album form. On the contrary, LPs seem to have survived as material objects. CDs only sell at concert venues, so I make them as if they were mementos. From now on I’ll be making songs from time to time and releasing them as they come, and I may or may not assemble them as an album eventually.

- Your roots are in “Ainu music”, but how would you characterize that genre? Do you run into any difficulties making songs?

- The arrangement for the song “Battaki” on my second album Hankapuy (1999) is based on a traditional song telling of the havoc caused by grasshoppers in the Tokachi region. I was surprised when Hosono Haruomi told me he could never get away with such an arrangement. Ando Umeko’s vocals are overlaid with a tonkori track, but it seems like none of the keys match. That seems to shock people whose ears are attuned to Western music conventions.

When Hosono-san made that comment, I wasn’t sure if he was complementing or criticizing my inexperience with pop music conventions, so my heart dropped, and I felt like an amateur. I couldn’t forget it. When having sessions and recording in the studio, I would often get scolded for not keeping things within the count of 8, or being off beat. Because I didn’t start performing music professionally until I was 33 years old, I would beat myself up for those mistakes, but those things didn’t matter at all when I worked with Umeko-san. Far from keeping to 8 beats, she would do things like switch the downbeat and upbeat or start singing at about the seventh of a beat. Adding to that swaying style, I seem to have recorded my tonkori riff in a completely different key. Looking back, I think we were getting at something really exciting. - It is indeed difficult to break free from a particular style of counting in 4, 8, or 16 beats or music played in chords and pitches based on the Western scale. One can’t play by different rules unless one can break free from the style one was trained in.

- Since Hosono-san’s comment, I avoided listening to “Battaki” until recently, all the while thinking I needed to perform “properly”. But this year, there were talks of putting together a 10-year best hits record in the UK, and the producer added “Battaki” to the list. I was thinking about turning down the selection at first, but when I heard the original song once again to check the mastering, I felt it really was something special.

Sure, it was all haphazard, but it became a very powerful tune precisely because I didn’t think it was haphazard. It felt a weight I’d been carrying for 20 years was lifted—or, as if grasshopper wings that had been stuck in my throat for 20 years were removed. The drummer is usually the one that bears the trouble of handling irregular rhythms, but Numazawa Takashi, the drummer of OKI DUB AINU BAND, understands me very well. He says, “OKI, you’re a Howlin’ Wolf (meaning I sing off the beat), so do what you want.” - In a previous interview, you mentioned that the tonkori has no frets, so it acts as a “rhythm instrument” rather than belonging to the guitar family. Even though the tonkori can produce only five or six notes at a time, the possibilities are endless if we think of it as a rhythmical instrument. Ando Umeko has also said that Ainu music is about rhythm and improvisation. How important is rhythm in Ainu music?

- What I’m trying is to break past the genre of “Ainu music” and create a hybrid genre. If I were to say that the tonkori is quiet so the drum should also be played quietly, then the drum would need to adapt. On the other hand, I could ask myself how the tonkori could adapt to the natural volume of a drum. This is why I created an electric tonkori. As to whether asking others to adapt to fit Ainu circumstances or whether to approach from the Ainu side, I would go with the latter. The irregularity of rhythm in Ainu music makes it pretty tricky to play as a group with other instruments. It often irritates other members, like when it’s off by one beat. When I listened to “Battaki” again, I noticed the vocals kept starting on different beats. Of course, Ainu music doesn’t follow 4, 8, or 16 beats, and the way of counting is fundamentally different. But in a band, I need to decide whether the other person will bend to my conventions or vice versa. Instead of having others adapt to the Ainu way every time, I also want to meet others halfway, and that includes things like the question of [sound] volume.

- You’ve created a lot of experimental sound, but not for the sake of breaking [through] the boundaries of popular music, but instead, to find a middle ground for collaborating with others.

- That’s right. But recently, I feel I should stop trying to do things the “proper” way. In the past, I used to tune by intuition and, even if the pitch was slightly off, I still had the groove. But listening now, the off pitch bothers me now. My ears have learned to pick up the “right” pitch, so now I worry about things like tuning, or matching keys to make chords. On the other hand, songs like “kon kon” on my album Sakhalin Rock (2010) or “kenkeyo” on UTARHYTHM (2016) sounds very natural despite some of them being a parade of irregular meters.

- Both of those are mukkur (mouth harp) songs with arrangements directly inspired by a recording of Nishihira Ume explaining how to use your mouth to play mukkur.

- As a traditional tonkori player, Nishihira Ume was called on by various researchers. That recording was from one of the tonkori recordings she agreed to. She was asked if she could also perform some mukkur, which she thwarted by saying, “I’m spent and I can’t do everything today.” Instead, she began explaining how to use your mouth to perform mukkur, mouthing the sounds kon kon and kenkeyo kenkeyo. Those rhythms were jazz to me.

Lately, I’ve been thinking my music is conforming a little too much. Returning to organic ways to break convention is important, but it will take another push so I can be free to be myself. I never intended to be so strict with myself, but I wondered if I hadn’t lost that fundamental, open-minded approach that I used to have when I used to draw from those archival recordings to make my music. I need to rewind myself to who I was when I made “Battaki”. I have more skill, knowledge and equipment than I did before, but I think the feeling of not knowing what I was breaking down is worth holding on to. - Listening to your albums in chronological order, I noticed there are experimental and traditional aspects that appear alternatively . For instance, after No One’s Land (2002) caught attention for featuring guest artists from abroad and creating experimental sounds, you released your solo album Tonkori (2005), which was based on archival recordings and tonkori sounds evocative of classical music.

- That was the strategy at the time. When making one album, I would already be thinking of the next. So, I thought of switching styles from album to album between simple, classic ones and ones with the latest arrangements. I also thought of releasing albums one after another. Back in the day, Tower Records only had sections for Okinawa, Japan, and Brazil, yet there was no section called “Ainu music”. There was a CD of recordings collected by Kayano Shigeru shelved under “Traditional Japanese Music” with traditional Japanese instruments like the koto. That’s because until then, there were almost no “Ainu music” items for sale. So, I decided to release an album each year. This led to an actual section for “Ainu music”. Today, there are other people putting out CDs, but the reason they don’t catch on is because they aren’t properly mixed and mastered, and the musicians don’t approach the media or the distributors. These things are standard for professional musicians. What I did wasn’t unique, I did what musicians normally do. If there wasn’t a genre for what I was doing, I was going to make one. I was just doing what was commonly required in the music industry.

On the other hand, there are many people who hold their Ainu roots, its songs and dances, close to their hearts, even if they don’t intend to make a living from those activities. However, many of them have also experienced providing their own song and dance without knowing how exactly it will be used or what the outcome will be. In many cases, when a paid offer comes around, the larger framework has already been set, and the artists are expected to provide song and dance just to fit into the plans of those with financial resources. As a result, if the artist’s expressive work is used in a way they did not intend for themselves, they have no recourse but to cry themselves to sleep. That’s why just singing a song is not enough if your self-expression is precious and you’d like to share it with the world. Moving forward, I think it will be important to know whether you have agency over your own songs and dances and where those forms of expression are headed. Learn how to take back the reins when you feel something is off. That’s what it means to be a producer. - So, you’re not just passively introducing Ainu culture, but producing the actual platform for your own activities as a professional. It seems, however, not an easy task, especially since you are both a musician and a producer. It is already complicated and hard to be an artist with your ethnic roots at the core of your expression.

- No one can tell you how to become an artist. But recently, I’ve been thinking that those involved in Ainu culture have an extremely high level of respect for their ancestors, so there’s a limit to how accepting they are of new things, making it difficult to innovate. Even when trying to make something new, I feel there is a tendency to sing in the same key, dance in exactly the same angle, and perform with the same costumes. I don’t like how totalitarian that feels.

One way to shake things up and make it easier to create new things is to make use of outside influence. I think the Akan Yukar Utasa Festival is a good example of how external pressure can be leveraged. I have respect for the performers from Akan who, as professionals, are capable of adapting their creative expression to work alongside new frameworks or conventions, as well as engaging in new forms of expression without sacrificing their dignity. Still, while there were both Ainu and Japanese performers, it was more often the Japanese musicians or producers, mostly from Tokyo, who took the initiative in leading sessions and musical arrangements. Even so, maybe it’s possible that such a platform could be used for Ainu people to learn how to lead production for themselves in the future. - Jumping off someone’s framework and starting to make your own platform to perform seems like an important attitude for taking ownership of your own expression. Akan Yukar Utasa Festival 2021 featured both Ainu and Japanese artists who, as the word utasa in the title suggests, “come together” at Lake Akan. Unfortunately, the festival had to move online in 2021, but while most performers, including most Japanese ones, wore traditional Ainu clothing, you dared to wear a tracksuit. You gave a powerful performance of your song “topattumi” that has the lyric “a thief came to Hokkaido.”(*11)

- I thought I’d go ahead and say something others have difficulty saying. It might have angered some people. I think I’m doing this the old-school way, when things were more offbeat. These days, there’s an overhanging feeling that we need to behave properly and politely. I performed in a tracksuit because everyone else wears traditional Ainu clothing at the Akan Yukar Utasa Festival. I think I might have been the first to wear the konci (an Ainu winter hood) on stage, but recently both Ainu and Japanese people have been wearing it. In the OKI DUB AINU BAND it’s very simple: Ikabe Futoshi and I wear Ainu clothing because we are of Ainu descent, but our other non-Ainu members do not. They might wear something with an Ainu pattern for an occasion like an album cover, but I don’t have my band members dress in full wear to look like Ainu people.

- You also performed with emerging artists at the Akan Yukar Utasa Festival.

- Kanto, who acted in the film Ainu Mosir and performed at Akan Yukar Utasa Festival as a musician, came to me for advice before the festival. Instead of telling him what chords to use or talking about word choice, I asked him about his reasoning. We had a deep discussion about his intentions, what he did and did not want to say. This is how I approach things as a producer. I hope that younger artists break through all sorts of barriers, but I have different feelings when talking about expectations as an Ainu person or expectations for being a professional in something. I hope they find happiness in either case. I’ve never been one to insist others identify as Ainu, and I would never expect something of someone because they happen to be Ainu. Those decisions are up to the individual, and I wouldn’t want my words to change their life in that way. I don’t think involvement in Ainu activities is necessary. However, I think they’ll need to face their own identity one day, and I hope to lend a helping hand when that time comes.

I think it’s more important to find a profession to be able to put food on the table. It’s more about being a human than being an Ainu person. However, I think being Ainu comes with the hassle of dodging judgement and prejudice. Still, I think it would be great if each person could make a living in the profession of their choice. For some, that profession is connected to being Ainu, while for others, it’s not. Either way, that person is still “Ainu”. Likewise, it’s not as if all Japanese people know about the traditional lifeways that existed before WWII, and not everyone is working in the field of Japanese culture, right? - Might more young people pursue a career as an artist if they believed they could find happiness following their own path?

- I think that now is the time to be keeping skilled people who identify as Ainu on the radar. There are actually many people with Ainu roots. At my concerts, many people come up to me saying, “Actually, I’m Ainu.” When I ask them about what they do, I get all sorts of answers: belly dancers, bassists, surfers and more. Actually, I’d be glad to see more competition in the music field to the point where it’s like, “Ah, I can’t join the music festival this year because that other group took the spot.” I want to see more groups like my own emerge.

- The film Ainu Mosir (directed by Fukunaga Takeshi, 2020), which you mentioned earlier, is set in Akan with the cast appearing under their own names, just as you played the role of “OKI”. Because of that choice, the film has an oddly realistic quality despite being a work of fiction.

- I think this film will gain more importance as the years go by. People who see it 50 years from now might say, “Oh! Grandpa Kanto is young! That person is also there, but who’s that guy in the movie? This is what Lake Akan used to be like!” It’s quite exciting to think about that. There’s a scene where the main character Kanto refuses to participate in the bear Iyomante (*12) ceremony, but the reason was because of the script, in which the role of Debo was lying. In the ceremony, it’s important for the children to see the contradictory nature of an adult “returning” a bear spirit, who until the previous day was playing with them, to the world of the Kamuy (“spiritual deities”). When I myself participated in the ceremony the first time, I saw the bear’s life leave its eyes. It was an opportunity for me to radically change how I understand the concept of “cruelty”.

If it were my script, I would have made the character Kanto, who raised the bear, participate in the ceremony from the beginning, even if he refused to. I would have added a scene, just like how I experienced it, where Kanto would hold the bear’s warm organs in his hands, taken from its opened chest. The Iyomante ceremony functions like an educational program that happens over a couple of days in which Ainu people learn about how to interact with nature, including the core Ainu belief that the Kamuy and human beings are equal, that the Kamuy are welcomed as guests, and how to conduct ourselves in relation to those guests. During the Utasa Festival, when I asked the real Kanto what he would have done in real life, he said, “I think I would have participated in the ceremony from the start.” In Asahikawa, where I live, or for the children and young people of Akan, like the ones that appear in the film, being Ainu is nothing out of the ordinary because everyone around them is also Ainu. But films have made some people conscious of their identity. In a painful way, it’s similar to how I became self-conscious of the irregular counts in my music. One shouldn’t force awareness on others, and one shouldn’t make someone look like they have become aware of something they have not. - At UPOPOY, you’re also providing music for a nighttime projection mapping artwork that is presented in the summer.

- I had the young traditional performers working at UPOPOY join me in recording the song for the piece. They were very talented, and I had a great time working with them. But to be honest, I think I could have made something really good if I had been called on from the beginning of the project. I’m often asked to contribute music to a project that already has a fixed team and contents, making it difficult for me to put out something interesting. This time, I just focused on making the music cool, and really tried to make something both the performers of UPOPOY and I could be happy with. I understand that creators who worked for the artwork probably just worked hard and earnestly, but the fact that this particular projection mapping artwork was assigned to those who, until yesterday, have never attempted anything Ainu-related is a mystery to me. I can create films, have friends to call on, and can produce artwork like that, but no one asked me to (laughs).

- Instead of providing just music or songs, it is important to be involved in the framework itself as a producer. What do you consider important when you act as a producer?

- Producing is about deciding criteria. Taking my music for example, I need to decide whether to settle for the “do-re-mi” conventions of pop music or lean towards the conventions of Ainu music. Either decision is correct, and either is a strategy. At first, I aimed to bring tonkori into the world of popular music, and I’ve transformed tonkori into something that can be performed in front of 50,000 people, but that required quite a few compromises. On the other hand, there are things I could never compromise on concerning what makes Ainu music unique. Listening to old recordings, the pitch and rhythm are all over the place. But when listened to as a whole, those irregularities don’t bother me at all. It’s a mono sound source meant to be heard as one. I think that is very “Ainu”. No one has any say on how Ainu music should or can be mixed with other music, and those mixes can’t be denied. To compromise on my end or have the other side compromise. This is something I always keep in mind when I produce Ainu music.

- So, it’s fair to say that you produce “Ainu music”?

- Even if I do something “current”, I have a sense that I want to keep things “Ainu”. I want to put forth my true form. Knowledge can be studied, but when it’s not knowledge or experience but your sense of self that your music embodies, imagine what you’re capable of creating. I used to decide on a bassline before I’d start recording in the studio, but with the new music I’m making now, I decided to go into the studio with just a song in mind. These days it’s important that I can make music in this uncomplicated way. I was enjoying myself when I made “Battaki”, and I want to remember what it was like back then when I made music intuitively. The other most important thing is to have saudade and sensuality. It is music, after all, so I put my heart into it. What my music needs is that gripping feeling.

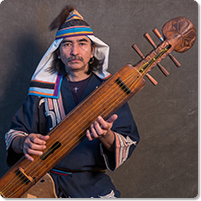

OKI

The Music of OKI’s World

Rooted in the Tonkori and the Unique Expression it Inspires

(c) Guoqing Jiang

OKI

Kano Oki, known as “OKI”, was born in 1957. To date, OKI has released more than 20 original solo, group and dub remix albums.

His album Tonkori (2005) established what could be called “classic” tonkori music with performances built on the sounds of his predecessors—including Nishihira Ume, Shirakawa Kuruparumah, and Fujiyama Haru (Esohorankemah)—that were collected by researchers around the 1940s and 50s.(*2)

From his debut album Kamuy Kor Nupurpe (1996) to his latest works, OKI has continued to feature Ainu lyrics and voices. In addition to traditional songs handed down to today, OKI has released original songs created with Kuzuno Tatsujiro ekasi (*3) in the Ainu language. Further, the songs “Oroso Omap” and “Tawki” on the album Sakhalin Rock (2010) feature unique Ainu lyrics created by the children of Asahikawa Ainu Language School in Hokkaido.

While valuing both classical Ainu music and cultural identity, his albums like OKI DUB AINU BAND (2006)Sakhalin Rock (2010) achieve a genre-fluid music expression that infuses blues, reggae, dub and more. In addition, OKI’s third album No One’s Land (2002) mixes voice recordings from the UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations (which he attended in 1997) with guest artists such as Indigenous Chukchi singers and East Timorese poets.

OKI DUB AINU BAND—a band formed and led by OKI that includes Ikabe Futoshi (tonkori), Numazawa Takashi (drums), Nakajo Takashi (base), Uchida Naoyuki (dub mix), and HAKASE-SUN (keyboard)—has been invited to perform at numerous music festivals in Japan and abroad, including one of the world’s largest music festivals, WOMAD (Australia, 2004 & 2017; UK, 2006; Singapore, 2007) and the Rainforest World Music Festival (Malaysia, 2019). As a music producer, OKI heads the music label Chikar Studio and produces the vocal group MAREWREW that recreates/inherits traditional Ainu songs. Ando Umeko (1932-2004), known as a master of both mukkur (mouth harp) and upopo (songs), participated under the same music label since OKI’s second album HANKAPUY (1999).

OKI Official Website “CHIKAR STUDIO”

https://www.tonkori.com/

Interviewer: Mio Yachita (National Ainu Museum)

*1 Tonkori

The tonkori is a traditional string instrument of the Ainu people. While the tonkori was partly used in northern Hokkaido, materials and ways of playing the tonkori are now reported to have originated in Karafuto (present-day South Sakhalin).

*2 Some of these sound sources are currently available online via the Hokkaido Museum, the Koizumi Fumio Memorial Archives (Tokyo University of the Arts) and Waseda University. These sources can also be found in the National Diet Library and various other museums.

*3 Kuzuno Tatsujiro ekasi (1910-2002)

Kuzuno Tatsujiro was a well-respected elder who was fluent in the Ainu language and was knowledgeable of Ainu rituals in Shizunai, Hokkaido. Ekasi is an Ainu term for a male elder.

*4 UPOPOY: National Ainu Museum and Park opened in 2020 as a composite of three facilities, named in the Ainu language: an=ukokor uaynukor mintar (National Ainu Park), an=ukokor aynu ikor oma kenru (National Ainu Museum) and sinnurappa usi (Memorial Site).One important context for UPOPOY and the Ainu people is the assimilation policy laid down by the Japanese government during the modernization efforts that started with the Meiji Restoration.

In the process of colonizing Hokkaido, Karafuto and the Chishima (Kuril) Islands, the Japanese government deprived the Ainu people of their rights to land and resources, banned hunting, gathering and cultural customs, and imposed Japanese-language education. Such policies brought severe damage to the lives and culture of the Ainu people.

In 1997, the Ainu people were recognized as “Indigenous” for the first time following the Nibutani Dam Case, filed by the first Diet member of Ainu descent, Kayano Shigeru and others. That same year, for the first time in about 100 years, a new law commonly known as the Ainu Culture Promotion Act of 1997 was enacted.

Following the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIPs) in 2007, both houses of the Japanese Diet unanimously passed a resolution in 2008 urging the administration to recognize the Ainu as “Indigenous Peoples”, which led to the establishment of the Advisory Council for Future Ainu Policy. Following the recommendations of the council, progress began on developing “a symbolic space for ethnic harmony”.

In 2019, the Act on the Promotion of Measures to Realize a Society That Will Respect the Pride of the Ainu, known as the Ainu Policy Promotion Act of 2019 was enacted, and the Ainu were finally legally recognized as “Indigenous Peoples” for the first time.

UPOPOY is operated by the Foundation for Ainu Culture, which formed in 2018 with the merger of the Ainu Museum (a private organization run mainly by the Ainu people for many years in Shiraoi-cho, Hokkaido) and the Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture that was established under the act of 1997.

*5 According to the National Museum of the American Indian, “American Indian”, “Indian”, “Native American”, or “Native” are all acceptable terms to be used. The museum states that “in the United States, ‘Native American’ has been widely used but is falling out of favor with some groups, and the terms ‘American Indian’ or ‘indigenous American’ are preferred by many Native people,” although it is preferable to use specific tribal names.

*6 In the Ainu language, samo refers to people of the ethnically Japanese majority (in Japanese, wajin). Alternatively, the Ainu word sisam, meaning “neighbors”, is also used.

*7 Mayunkiki’s first solo exhibition, SINRIT teoro wano aynu menoko sinrici a=hunara, (From here, we look for the Roots of Ainu Women) was held at CAI03 in Sapporo between January 19-30, 2021.

https://cai-net.jp/exhibition/

*8 Kayano Shigeru (1926-2006)

Kayano Shigeru was the first Ainu person to become a Diet member in 1994 and, for the first time in history, to pose questions to the Diet in the Ainu language. As a cultural researcher himself, he collected Ainu implements and recorded oral histories, of which a portion is currently designated as Important Tangible Folk Cultural Property.

*9 Kawamura Kenichi (1951-2021)

For 40 years from 1983, Kawamura was the Director of the Kawamura Kaneto Ainu Memorial Museum in Asahikawa, Hokkaido. He also served as the President of the Asahikawa Cikappuni Ainu Culture Preservation Society, one of the designated preservation associations for Traditional Ainu Dance that is recognized as Important Intangible Folk Cultural Properties.

*10 See note 3.

*11 Utasa Festival 2021 is viewable online on Youtube: DAX -Space Shower Digital Archives X.

https://www.youtube.com/

*12 Bear Iyomante is a ceremony in which a bear cub, caught during bear hunting, is carefully raised by the village until it grows up, when it is “sent off” to the world of the kamuy (“spiritual deities”).

Related Tags