- You entered the Film Production course in the Performing Arts Dept. at Kyoto University of the Arts in 2001. It was a course that was started at the same time the school became a 4-year university, and yours was the second class, wasn’t it? That means that there were no graduates of the course who were already active in the arts world, which means that you chose the university and the course simply on the basis of the information you could find. Did you already have an interest in film and theater at the time?

- In the 1990s, there was a popular subculture of cross-over arts, and since I was raised during that time, I had a general interest and attraction to the full spectrum of the arts and culture. I have a brother four years older than me and I always looked up with admiration to the things he did, like playing in a [rock] band and the fashionable clothes he wore. I copied him by playing in a band too and wearing his clothes without permission.

My brother went to Seian University of Art and Design in Shiga Prefecture and studied in the Film Course there. So, I quickly began to search not for a regular university but an art university, and specifically one with a film course. I applied to Seian University of Art and Design, but I didn’t get in. I had intended to study another year to pass the exam there, but I had also applied to Kyoto University of the Arts and happened to get accepted there, so that’s where I went. So, it wasn’t the case that I had specifically chosen the university with the desire to study theater or film, it was more of just a general attraction to the arts. - So there weren’t any specific professors or artists that you had in mind?

- None at all. I didn’t really know any specifically. So, when I got to the university and others were asking me if I came there because I wanted to study under Ito Takashi (an experimental film director) or Akio Miyazawa (a playwright and director), I felt embarrassed that I didn’t even know them. It wasn’t until after I started university that I learned about them, but to answer I made up lies like, “I read Miyazaki when I was in high school.”

- When was it that you first began creating your own works at university?

- Our university was a bit strange. Even though I was in the film course, I was told one day to go out and buy a yukata (light cotton kimono) and was made to learn Japanese traditional dance. And students who were in the theater course were suddenly given a camera and told to go out and shoot something. It seemed that film and theater were the same thing. It was probably in my third year of university that I made something for the first time.

- Was it a film work?

- No. The first thing I did was a stage work. I directed So Kitamura’s play Hogi uta. A friend of mine planned the production, and since he planned to act in it, he asked me to direct it. And that was the first time. I did it without knowing anything about what directing a stage work involved. I read the script, trying my best to find what the writer wanted to say, and in that first attempt at directing I tried to do what I thought a director would do, saying things to the actors, like, “These lines are especially important, so you have to put something more into them.”

- Was the first time you became involved in a theater production outside of university in Kyoto’s theater scene the 2004 work with Motoi Miura?

- Yes. It was the play Jaguchi Wo Hinereba Mizu Ha Deru.

- I was involved at this time too, so I can give some background about what was happening. In 2003, the actress Junko Uchida-san received a grant of 3 million yen from Kyoto City’s special program for supporting young artists. With that, Uchida-san set up a project with the French Actor Pierre Carniaux to do a production of the theater work Jericho. Chosen as the director was Miura-san, who at the time was a member of the directing department of the company Seinendan. That was in July of 2003. Deciding that he wanted to use video in that production, Miura-san went to Masataka Matsuda, who was teaching at Kyoto University of the Arts at the time, and he was given an introduction to Shimpei Yamada-san. Yamada-san is a videographer who in recent years has worked on the stage productions of Teppei Kaneuji and the video theater works of Chelfitsch. After that, in 2004 there was a new project to produce a work by Miura-san under the sponsorship of the Kyoto Art Center theater project that I had planned, and they needed a directing assistant. For that, Yamada-san introduced us to you. I was there at the first meeting between you and Miura-san in April of 2004 at Atelier GEKIKEN, where the CHITEN production of Three Sisters was to be staged.

- That production of Three Sisters was a very impressive experience for me. It was one of the first plays that I saw outside of our university, and to see a production like that all at once, not knowing anything about what was going on, except that the momentum of it was amazing.

- Eventually, that Jaguchi experience led to you working with CHITEN and Miura theater works for the next five years.

- Yes. After meeting Miura-san, I did one work at the university, which was like a collage of based on scripts by Shuntarō Tanikawa and others. I asked Miura-san to come see it, and what he told me afterwards was that I was only looking at one spot. I remember very clearly that he told me that the audience sees the whole stage, so I should learn to see not just what is happening on that one point I am focused on but what is happening on the entire stage. There were a number of other things that he criticized me for, but in the end, he told me, “Theater is fascinating, isn’t it? You want to keep doing it, don’t you.?” I didn’t really feel that way at the time, but when I hear those words from him, I did indeed want to keep doing theater. Those were words that really motivated me, and I will never forget them.

- Meanwhile, your graduation work was a film work, wasn’t it?

- That’s right. It was a documentary film.

- Was it a work connected to your interest in theater?

- At that time, I approached working on a theater (stage) piece and working on a documentary film with two completely different mindsets. To begin with, I had never seen a documentary type theater work, and I didn’t even know such a thing existed. What I had learned about theater works was all from my five years working with CHITEN, including what the job of directing involved, how a performance is put together, how to get funding, and what the lighting and audio work involved. All the things I knew about theater had been learned there.

I had thought of the job of a director’s assistant was mainly performing odd jobs like taking notes on what the director said, contacting the people involved to convey the director’s requests, organizing the costumes, cleaning up and the like, but what Miura-san told me was to just stay by his side and watch everything with him. That is all I was told. At times he would ask me what I thought of a scene, and I would reply things like, “Well, it didn’t seem to be very interesting to me.” I felt like I was there all the time being someone he could talk to for a second opinion. I also spent that time thinking hard about ways to make things more interesting. It was like intense training in coming up with ideas. There were times when the actors asked me to directly propose ideas on their behalf. But none of the ideas were ever actually used in the final performances (laughs). The final decisions were always made by Miura-san. It may have been that the ideas were coming to him during that time he spent talking with me. - When you left CHITEN in 2009, what was the theater world like at the time in your eyes? That was around the time when Festival/Tokyo had been started under the direction of Chiaki Soma. Did you have any clear vision of the activities you wanted to pursue?

- I didn’t have any at all. To be honest, I wasn’t really thinking much about it. To friends, I felt a bit embarrassed to call myself a director. I was still drifting, helping out in the works of other artists, and I worked part-time doing photographic recording.

- I imagine that one of the things that eventually led to your current working method might have been your involvement with Tsuneichi Miyamoto (*1).

- After spending all that time at CHITEN, I felt it would be beyond my capabilities to direct a production of an existing play. I couldn’t compare with Miura-san. One day, the stage artist Itaru Sugiyama-san introduced me to Tsuneichi Miyamoto’s book The Forgotten Japanese and I was really impressed by it. I was interested by the way the book was written (not on written histories but) by actually walking the country and doing research on the now lost lifestyles of the Japanese people. It wasn’t written like a book by (folklore scholar) Kunio Yanagita, and it wasn’t the kind of mysterious or magical writing style like that of Shinobu Orikuchi. I liked Miyamoto’s stance as a writer who didn’t convey himself as an author but just recorded stories he had heard or descriptions of the roads he traveled just as they were.

Miyamoto’s photographs were also wonderful, so I wanted to print them out large and hang them above the stage in the stage design. Their feeling had a wonderful anonymity, like an abstract person appearing in the woods speaking the words of “the Forgotten Japanese” or listening to them. At a time when I was still trying to express things for the sake of expression, or when I was obsessed with my own interpretation of what I thought “expression” was, this encounter was really overwhelming for me. - It was great that you didn’t give up after an experience like that (laughs).

- The reason that I didn’t lose my motivation was because I still had an image that somehow things would go well for me. I guess I had long been thinking about what I could do to get closer to works that were really mine, works that would be closer to what I really wanted to do. That is why quitting was never really an option that I had considered. Since I had always wanted to get to the point where I could say, “This is truly my work,” I was able to continue.

- I believe it was the following year that you had your breakthrough with Zeitgeber (2011).

- It was in 2010. The stimulus came when I was preparing for the Miyamoto work. In one of the actors who would later perform in Zeitgeber, Shuzo Kudo, I felt such a stiffness in the presentation of his lines and in his movement that his inherent appeal as an actor wasn’t coming through. I knew that he was working part-time as a caregiver, so on a whim one day in the rehearsal studio I asked him to show me some of the actions he performed in that day job. And what he did was so interesting. As I watched, I felt that even though I hadn’t written any script for it, and I hadn’t given him any direction, what he was doing was true theater. None of his movements or words were what I had intended but is all made sense and was very appealing to watch. I was truly astonished by the way his actions embodied all of the appeal that I had anticipated from him. But, because I didn’t see how that could be translated into a stage performance, it ended there. Still, despite the frustrating experience I had with the work of Miyamoto and the feeling I had after that there was still something I could, that there was still some answer I could find, it was that experience in the rehearsal studio that day that I remembered. And with that in mind, I set to work, not knowing if my efforts would meet with approval, and not really caring if they did.

Thinking in terms of what is really necessary, his presence alone was enough, there was no need to elaborate about the lighting or the audio effects. It wasn’t as if I was determined to do something in theater that no one had ever seen before, it was rather that with this work I wanted to try for the first time to simply eliminate all of the things that I thought were not really necessary. There was truly no waste involved in the movements of the caregiver’s body when at work in the tasks of caregiving, and I payed attention especially to the way he handled the body of the person in care. I also liked the human relationship between the care giver and the care receiver. The two were not family and they weren’t friends. Although theirs was a relationship of two unrelated people, but within the close physical contact required in the caregiving workplace, it became a close relationship. But, because work is work, there was an unemotional detachment to the relationship as well. The way those aspects coexisted seemed ideal, as well as fascinating to me.

Another influence at that time was the fact that I had just seen a Contact Gonzo performance for the first time and had been very struck by it. That performance took place during their exhibitions at the Kyoto Art Center, and to see their performance that involved full-strength striking of each other was so fascinating that I almost burst out laughing. Seeing that it was enough for them to perform only with the props they had brought in by hand to the space was something that encouraged me, and I felt that I had seen a new realm of potential for stage performance. The only equipment I used in Zeitgeber was a guitar amplifier, and what’s more, it was one that happened to have at home. And it was also at a time when I had begun to encountered new things I hadn’t seen before while working as a director’s assistant for Akira Takayama’s Compartment City – Kyoto. - This is the first time I have heard you talk about Gonzo. I have heard that you were directly influenced by the documentary theater trend that had begun to appear in Japan at the time, but I am very surprised to hear that you were influenced by Gonzo.

I would like to ask you to tell us a bit more about your experience with Zeitgeber. In order to have Kudo-san do his caregiver performance on stage, you took some initial measures. First, you came out and stage and said, “Now we are going to begin,” and then the performance started. This introduced the conditions that the stage would begin under and changed the audience’s state of consciousness. Next you solicited someone from the audience to come up on stage to play the role of the care receiver. This introduced a new set of uncertain elements each time. With devices like this you introduced a number of “frames” to share with the audience which frame they should focus on in each scene. - In fact, that wasn’t the way I planned it from the beginning, it just turned out that way. The format in which you could see multiple structural layers was the result of a working process that involve developing scenes one by one and putting them together until some realization came. Originally, I wasn’t planning on having members of the audience come up on stage to take part in the performance, and during the rehearsals it was done completely as pantomime with Kudo-san going through his movements and words of explanation accompanying his actions. However, shortly before the first actual performance I was still thinking that it would be OK to do it purely as an “air” performance without a care-receiver involved, but soon I got the idea that it might be good to have an actual person in the care-receiver role. But, at the same time it would look strange to use an actor in the care-receiver role, and it wouldn’t be right to bring in an actual care-receiver from a home or someplace.

Around that time, I was often drinking with the artist Masamitsu Araki-san (*2), and he played in a band and often spoke about the Osaka live-performance houses. They were places he frequented where you could hear some strange bands and see interesting performances, and a lot of them were people who hung out around Tetsuya Umeda. When he talked about one rap artists who would have the audience come up on stage with him, that gave me the idea. “That’s it!” I thought, I could bring someone from the audience up on stage for Kudo to work his care-giving routine on.

When I was working on Zeitgeber, I had come to think that I wanted to be sensitive to the handling of emotions. And I thought that if I had Kudo-san work with a member of the audience he had never met before and have to touch the body of a complete stranger like that, it would be close to the tension that exists when he is working on a person with disabilities at his job. Also, as for not having the events start from me, that feeling of things not beginning from me was something close to the feeling I had when working on documentary films. - A work of yours that followed along the same line of development as Zeitgeber was Independent Living (2017), which you did as part of the East Asia Capital of Culture, Kyoto program, and it was a work where you were given the set theme of Japan, China, Korea.

- That was one I really had a difficult time with. I felt that I had to do something meaningful, but not just selecting some problematic issue to focus on, I rather wanted to do something that showed the current states of the three countries, so I decided that it would be good if I could find a way to show three contemporary faces of Japan, China and Korea. There is a work filmed and directed by the American film director James Benning titled California Trilogy. It is a work that shows a sequence of two and a half minute shots of scenery taken by a fixed-position 16mm camera. I always liked that work. Even though it involved nothing more than Benning choosing the site to film and then pressing the ON button, each segment somehow tells a story, somehow communicates something. It was a work that portrayed various faces of California, ranging from industrial areas to rural districts. From the scenes you can perhaps read histories of excessive development and environmental pollution, but you can also read the scenes as ones of peaceful fertility. So, I decided that is what I wanted to do for this project.

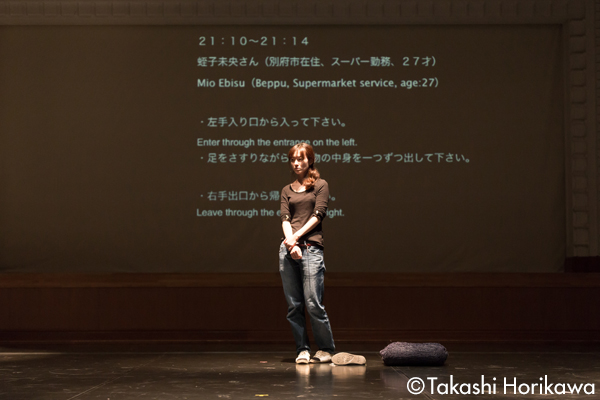

So, I thought about the possibility of reproducing on stage scenes I filmed in, China and Korea. I imagined using large numbers of extras to stage scenes, but I realized the logistics would make it impossibly difficult (laughs). So, when I thought about what to do, I suddenly remembered Zeitgeber and decided to do something using Japanese, Chinese and Korean caregivers. We did the first performance at KYOTO EXPERIMENT, but there hadn’t been time to do rehearsals, so it ended up being a very unsatisfying experience. But, when we did a restaging of it in Germany, I was able to take the time to redo it properly and it turned out to be a very successful work. - I believe that another work that became the origin of a large vein of your work was Everett Ghost Lines (2014). This was a work that involved sending out letters to a large number of people with the purpose of having the stage performance proceed based on the instructions written in the letters. The instructions written in these letters direct the recipients to come to the performance venue and perform the actions written in them, and in fact some people did come and perform the prescribed action, while others came but did not perform them. In fact, there were people who did not come, and others who could not come (deceased). The contents written in the letters were projected on a screen at the back of the stage, so the audience already knew what was to take place on the stage. So, for the audience, it became an experience of constantly shifting awareness of the gap between what they expected to happen and what actually happened. What was it that led you to this concept?

- The origin lay in the fact that, after Zeitgeber, I felt there was a problem in the fact that it was only after an encounter with someone like Kudo-san that I could begin to develop a work. So, as I thought about how I should change the approach for my next work, I wondered if there was a way that I could create something where it didn’t matter who was performing in it. But what was the inspiration really? In fact, I had filmed a documentary work after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami that I titled “Out to sea.” When I interviewed people for that film, they all said that at the time of the tsunami they were all thinking about where their family and friends were and whether they were alive or dead. In other words, there are moments like when your father might have died, or someone might have been hit by a car and no one would know it, would they? Normally we feel assured that the world is turning, and life is going on as normal, but in fact there is always the danger that something is happening that we can’t grasp. When actually the world is always full of uncertainties, and when I thought about how that could be expressed in a stage work, this was how it turned out.

- How did you decide on the title? Some propose that the title has to do with Everett’s many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics.

- At the time I conceived of the structure for this work, I didn’t know about Everett’s many-worlds interpretation. There is a movie by Masao Adachi titled Ryakusho / Renzoku shasatsuma A.K.A. Serial Killer that is about the serial killer Norio Nagayama (*3). It may be connected to what we said earlier about Benning, but it was a film that consisted simply of a compilation of footage that Adachi filmed at the places where Nagayama was actually born and raised and would probably have seen during that time and until he committed his crimes was eventually caught. What we see in the footage is just scenes like middle school students riding bicycles to school wearing helmets as required through rural countryside, but the viewer can’t help but imagine that perhaps it was because he saw this kind of scenery that Nagayama turned to killing people. We also see things like flashy signs in the towns, and rather than some feelings of hate or the like, it may have just been the site of everyday trivialities like this that drove him to kill impulsively.

In the film, there is nothing that speaks about what drove Nagayama to commit the crimes, but when you see the scenery in the film you get the feeling that you begin to understand the reason. In that movie, there was a brief shot of a sign or something with the words Everett Ghost Lines on it. I thought it looked cool, so I used it for the title.

It was only after that when I did some research on Everett and found that it was a place name in the U.S. and that there was a theory of quantum mechanics called the Everett many-worlds interpretation. And I was really surprised that it happened to connect to the existence of parallel worlds that I was thinking about doing a work on. So, the title came as an after-the-fact explanation. - There have been several variations of Everett Ghost Lines. Standing out among them was Version B – Faces, which revolves around a specific person who is not present. It is a professor from your university who passed away at a young age, the documentary film director Makoto Sato. It was your documentary film that was shown at the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival. I would like to ask you next about that film Version B – Faces.

- I had an idea that was completely different for the device I used in Everett Ghost Lines of sending out letters to potential participants with instructions for them. It was influenced by the film Shoah by Claude Lanzmann (*4), and the idea I wanted to try was doing interviews of several people who had shared the same experience. I can’t remember at all why I decided to use that for a version of Everett Ghost Lines, but I guess it was because I didn’t have the confidence that it could stand alone as an independent work.

When I thought about a group who had shared the same experience, I thought it would be good to use a group of people who knew each other and had lost a common acquaintance. I got the idea to have that group gather together and have them talk about the acquaintance that had died. The one who immediately came to mind once I had decided that was Sato-san. I also had the fear that I personally had too many thoughts about professor Sato that weighed heavily on me, but I couldn’t help the fact that he was the one who immediately came to mind, so I decided to make him the subject. I had a group of the former students who shared the same feeling of being left behind when Sato-san passed away, and I created that version by interviewing them numerous times. Then I thought about how to bring out that great sense of loss they all shared in the context of seemingly trifling interviews. - The format of the film is one in which you interview each of the members of that group.

- There were several devices I used, and of those the biggest device is that at the start of the interview I set a timer for two or three minutes. Even if it came in the middle of a thought—“Well, then, let me remember …”—as soon as the timer went off, the interview ended at that point. The fact that the story was cut short in the middle and was followed by a period of silence left a sense of lingering expectation. And in that silence there was an embodiment of Sato-san’s absence. The set questions I used in the interviews were who they had first heard about Sato-san’s death from and what they were doing at that moment. And I prepared a final scene at the end of each of their interviews where, after I had left the room, they were left facing the empty seat where they could imagine Sato-san sitting and they could converse with him in parting.

- In that sense, you were interviewing them about both the facts of what they were doing when they heard of Sato-san’s death and what their thoughts were about him, weren’t you?

- One of your recent works is the one titled Moonlight that you presented a restaging of at Festival/Tokyo 20. This work started as a project with ROHM Theater in Kyoto and was created in a tie-up with five regional Culture Centers in the city. The plan involved five artists or groups participating one each at the five centers to create a work, and you participated with the Nishi Culture Hall. Was it you that chose to work with the Nishi Culture Hall?

- Yes, it was. I looked at all the centers and decided on Nishi Culture Hall.

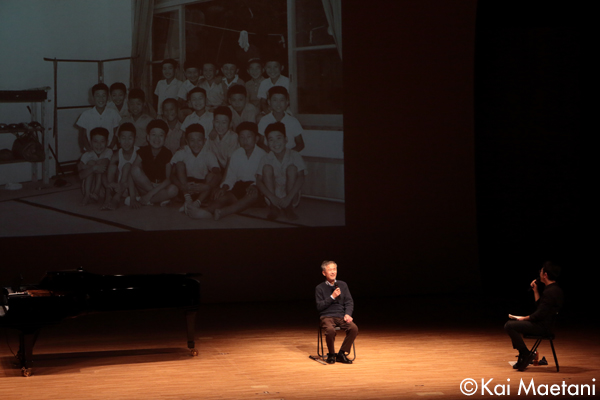

- Nishi Culture Hall is in Kyoto city’s Nishigyo Ward, in a new housing district. In order to decide what to do there, I hear that you visited the center and the area numerous times to do research. From that, it appears that you became interested in the fact that there are a great number of piano recitals held there by students of the local piano teachers. That became your starting point for the work, didn’t it?

- That’s right. In these piano recitals, the youngest students perform first and then the order goes up by age to the high school age students, and I felt that it becomes something like a story of each child’s life. At first, I wondered if I could use the piano recital as a format to tell the story of one child’s growth. For the main character, I would have someone who played the piano their whole life, into their 80s and 90s, and the idea was to have different people act the part of that character in different stages of their life. But I couldn’t find a person to fit the role. The reason was that, there are actually very few people that continue to play the piano as a hobby their whole life, other than those like professionals who become piano teachers.

As I was making phone calls trying to find someone, one piano teacher told me they knew a man who was still playing in his 70s, although he had rather poor eyesight. That man was Akio Nakashima-san. When I met him, I found him to be very interesting to talk to, and although it had nothing to do with the fact that he had poor eyesight, and I decided on him immediately. In Nakashima-san’s case, he wasn’t one who had been playing piano from childhood, but when he said that he loved the piano and classical music, I felt certain that if my plan was to have him play some of the pieces from his life for the local people, it would be successful. - What was the creative process like?

- From the time I met him, I would go to Nakashima-san’s home almost every day and interview him. Then at one point, as I was looking back through all the film I had taken, I found that I could create a movie-like timeline from the film sequences I had, so I decided to piece them together that way. Then I told Nakashima-san what the process would be, and I had him practice just a bit. He went into it as almost a one-shop attempt for the final take. So it was difficult to re-produce that. It has been no more than two years since that first performance, but knowing his age, I could see that he had grown physically weaker in that time. I was really worried that putting a person like Nakashima-san up on stage again might be seen as an exploitive act of making a freak show of him. So, it was a difficult decision for me whether to attempt using him for a re-staging. But I told myself that this wasn’t a medical question but a question of theater, and so I decided that it would be OK if I took an approach of not showing a weak figure and what he could no longer do, but to try to search for what he still could do. Once I had decided to change my mindset and think about what he could do, I was certain that we could successfully do a restaging of the work.

- Hadn’t there been some conflict in your mind from the time of the first performance whether to put him on stage or not?

- Ever since Zeitgeber I had been worried about whether or not having the person him- or herself go up on stage was an act of exploitation. I don’t think that this is an issue that can actually be solved. Because one can’t say with 100% certainty that it is not an act of exploitation. But one small point that I think I can make is that it isn’t until after the performance is over that it is time to decide whether putting a person on stage like that is exploitation or not. It is after watching the performance that I think about whether it was acceptable or not. There may be some amount of time in my works when this is an issue, but at the same time there is a lot of time in the works when it is not. I don’t think there is much meaning in me making explanations, but rather the important thing is when you are watching in the midst of a performance, I believe.

It is the same when you are filming with a camera, but I believe that as long as theater is divided between the audience and the stage, there is a power structure in theater. It is a sort of relationship where the viewer side has their power and rights as viewers, and we on stage who are being watched are subordinate to that power of the audience. As long as you are dealing with that kind of relationship, there is no way to escape its consequences. I believe that is the nature of theater. It is not as if I deliberately want to make a show of weakness in the face of that cruel aspect, but I believe that there is no way that anyone can change that power structure. Certainly, as with when someone stands in front of a camera, when a person is standing on a stage, they should be feeling the tension. If you try to hide that tension and put a veil over it, the result is going to be an uninteresting work. It may sound a bit extreme to say this, but I feel that having a storyline and actors in different roles is a kind of veil. I think of it as a process to hide something, a way to give some warmth to the people on stage, you might say, or a way to eliminate the state of tension between those on stage and the audience. - By the way, on this project you were said to be working with a dramaturg, namely the translator and dramaturg Tatsuki Hayashi. Was that the first time you worked together with him?

- Hayashi-san is a very interesting person, and he influenced me tremendously. At the time, Hayashi-san was based in Okinawa, so considering that distance, I first asked him how we might be able to work together. Interestingly, to begin with he didn’t try to define what his role would be as a dramaturg. I got the feeling that he was thinking about what he should do while listening to the things I said and the way I moved. During that first discussion, it came to a proposal that we begin by making a proper pamphlet [about the project]. What really surprised me after that was the way he would always carry the pamphlet with him and pass it out to the customers at the pub in front of the venue and advertise the project to everyone, saying, “We’re going to be doing this performance at the hall nearby so please come.” He did that naturally with no hesitation, saying that the more people that came to see it the better. Seeing that, I soon started making a point of actively advertising it to people.

- Perhaps it was seeing the way that you did all the work of searching for performers yourself, from the phone call and everything, that made Hayashi-san decide that he shouldn’t interfere in that process in any way. In your works after that, it seems that you then included a series of dramaturg-like members.

- That definitely seems to have been the trend. In Pamilya (*6) (meaning family in Tagalog) I worked with assistant professor Yuichiro Nagatsu of the Department of Communication Design Science in the Kyushu University Faculty of Design known for his broad-reaching research on the subject of disabilities and art. This was the result of having met him at ROHM Theater in Kyoto, where we were both participants in a discussion about disabilities and art. Because of the good results of having worked with Hayashi-san, I had begun to think positively about having a dramaturg on the creative team. When we performed Pamilya in Fukuoka, I was fortunate to have Nagatsu-san make a good pamphlet for us.

- That pamphlet took the form of a sort of production outline that revealed a chronology of how many times you had visited the character Jessa’s workplace and built a relationship. And that kind of documentation also reveals a lot about your working method as an artist.

- When viewed from another perspective, it seems like there is a consistent theme of the problems of communication. In Zeitgeber as well, the question of how the caregiver and the care receiver communicate emerges, and in Everett Ghost Lines also, with the process of sending out letters to people, there is uncertainty as to whether the message has been communicated to the recipient or not. In these works of yours with their foregrounding, although it hasn’t been talked about much, there are Rashomon and the Japan, China, Korea Project, in which the subject of “Fools speak while wise men listen” that comes out as if by chance part way through.

- Now that you mention these, I feel that both were arrived at as a reaction to something. In the case of Rashomon, I had been given Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s book by the same name as my theme for a project, but I didn’t want to just take my interpretations of the author and the novel and project them into a contemporary setting. If I didn’t touch on the novel at all and if I didn’t arrange a composition, what could I do? What came to mind at that time was to give it to foreigners to deal with as they would. So, the title of the piece didn’t matter, and the subject of the piece became what a German woman who didn’t speak Japanese and a Japanese man could or could not communicate using only gestures.

The work Fools also came as a reaction, when I was selected to serve as an East Asia Cultural Exchange Ambassador and sent to China, I didn’t want to internalize the common message that even though our two countries had political and historical conflicts, through culture we could surely reach mutual understanding. I didn’t want to pretend that, even though I saw discriminatory statements and actions regarding the people of other Asian countries on almost a daily basis, we could reach congenial understanding under the name of culture. Rather, I had the feeling that I wanted to present a straightforward picture of the relationship between the Japanese and the Chinese, which is something that most people don’t want to hear about, and not hide the fact that it can surely be said to involve plenty of mutual discriminatory feelings and opinions. - I think Fools speak while wise men listen stands out among your works as one that evokes feelings of jealousy and prejudice among the viewers and brings out the negative feelings of discrimination. I felt like we had to look the realities, not as someone else’s problem but one that brought out painfully our own feelings, which made it very interesting, but at the same time very uncomfortable to watch. In short, it was a rather wrenching experience.

- In our minds, I think almost everyone certainly wishes we could have a world free of discrimination, and that is why there are realities we wish we could hide. But this was a work that brought out the truth we don’t want to see. The creative process began from having a group of Chinese exchange students and a group of young Japanese go through a “Nice to meet you” conversation, and in the rehearsals, we created dozens of different patterns for the conversations. These young people who had never met before were brought together for the first time in the rehearsal studio, and in the course of one day they were asked improvise conversations base on about three different episodes. The next time they met at the studio they were asked to try other conversations, and this process was repeated. In the end it was only the conversations recorded on the first day that remained. As might be expected, it was the honest tension of that first “Nice to meet you” conversations where both sides were nervous are the ones that remained. So, even though they eventually became friendly, it was probably a rather painful experience mentally to have to go through the same tense conversations of the first day over and over with each performance.

- At the opening performance, the dialogue was repeated four times.

- Yes. Each of the four teams repeated the conversation four times. With each repetition, the tempo and pauses in the conversation changed. The first time, the conversation sounded rather plain with nothing exceptional, but injecting a slight blank of time in between seemed to cause a tremendous discontinuity. Although the contents of the conversation were just trifling formalities, the performance time was arranged in a way that emotions that had been hidden at first were somehow brought out one after another. As a performance, it ended with the initially friendly feeling between the participants eventually becoming very unfriendly.

- There were points where the exchanges began to sound argumentative, and as the conversations were repeated you could feel the power politics between the participants changing, which was very interesting to watch. It made me feel that a lot of thought and calculation had gone into the work’s creative process.

- I did put a lot of effort into it. From the outset, the whole situation in the rehearsal studio of asking the Japanese young people to speak to the Chinese students and vice versa was fiction in itself, so it all began from an unordinary starting point not found in daily life.

I felt that the interest you had brought to the piece intuitively succeeded in digging deep into the heart of the situation and thus opened up a broader vein on stage, as planned, that communicated to the audience.- Although this may sound like a rather abstract statement, I have a feeling that the “It is up to the stage to accept or not accept what happens there.” Personally, I often use the term “being kicked,” and it means, “If the stage kicks you, you have to realize that you have done something unacceptable.” I feel that I have long submitted to that rule.

Takuya Murakawa

Eyes that Focus Like a Camera on its Subject

The Vision of Takuya Murakawa

(c) Guoqing Jiang

Takuya Murakawa

Murakawa is a director and film artist. Born 1982. Lives in Kyoto. His works born of documentary and field work methodology and presented as film, stage works and visual arts have won him numerous invitations from festivals and theaters in Japan and abroad. The work Zeitgeber (2011) where a single performer gives physical caregiving to a single person in the audience invited on stage to receive it at that day’s performance has been restaged numerous times in Japan and abroad, and in 2014 it was performed again at the “Japan Syndrome Art and Politics after Fukushima” program at HAU Hebbel am Ufer in Berlin. Other Murakawa works like Everett Ghost Lines (2013), where the performers on stage act out instructions sent by mail to them, re-examine the methodologies of expression on the borderline between fiction and reality and search for answers to the questions of what true reality is in the real world. In recent years, his work Independent Living premiered at KYOTO EXPERIMENT Kyoto International Performing Arts Festival 2017 and was invited for restaging at Festival Theaterformen (Braunschweig, 2018), and his work Moonlight (premiered at ROHM Theater Kyoto “CIRCULATION KYOTO” and was invited for Festival/Tokyo 20). Chosen as an East Asia Cultural Envoy in 2016 (Japan Bureau of Cultural Affairs), Murakawa resided in Shanghai and Beijing, China and conducted workshops, and he was also chosen as a Junior Fellow of the Saison Foundation 2014-2019. Murakawa also serves as a part-time instructor at Kyoto University of the Arts’ Department of Performing Arts.

Interviewers: Yusuke Hashimoto

(*1) Tsuneichi Miyamoto (1907-1981)

Miyamoto Tsuneichi was a folklorist. As a student, he became interested in the research of Kunio Yanagita (Japanese native folklorist, scholar and Bureaucrat), after which his talent was recognized by Keizo Shibusawa (Japanese businessman and ethnologist) and he began studying folkloristics in earnest. He traveled throughout his life, and over the course of some 51 years, he did surveys in more than 3,000 towns and villages across Japan and left many records of his findings.

(*2) Masamitsu Araki

Born in 1981 in Yamagata Prefecture. In 2005, he graduated from the Film Production course of the Department of Performing Arts of Kyoto University of Art and Design (currently Kyoto University of the Arts). He has presented a wide variety of works ranging from theater pieces to installations. Among his main performance works are Ojisan to Umi ni Iku Hanashi (Kyoto Art Center lecture-hall, 2018) and Zofuku suru Heya (Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art). Among his major solo exhibitions are Acoustic Device − Five movements for the noise” (Tokyo Wonder Site Hongo, 2016) and others. He has works numerous times with other artists as a sound designer.

(*3) Norio Nagayama (born in 1949)

In 1968, at the age of 19, Nagayama shot and killed a security guard in a hotel in Tokyo, after which he shot and killed three people in Kyoto, and then sentenced to death in 1990. After being sentenced to death in his first trial, in his second trial consideration was given to his adverse home environment and his sentence was converted to life imprisonment. Japan’s Supreme Court reversed this decision of the second trial and resentence Nagayama to death in a decision now known as the Nagayama Standard for the death sentence based on the number and brutality of the killings. On Aug. 1, 1991 he was executed at the Tokyo Detention Center.

(*4) Shoah

A documentary film by Claude Lanzmann about the Holocaust (Genocide of Jews by the Nazis) with a total length of 9 hr. 27 min. (Part 1 154 min., Part 2, 120 min., Part 3, 146 min., Part 4, 147 min.). This representative Lanzmann film was based on some 350 hours of interviews conducted over the space of three years.

(*5) Moonlight

The subject of this work that takes the form of discussions with Murakawa and a piano recital is a Kyoto man named Nakashima in his 70s who began playing the piano because of his love of Beethoven’s piano piece Moonlight Sonata. Answering questions from Murakawa, he speaks about his encounter with music and reveals episodes from his life such as his eye disease that has continued from the age of 20 to the present, while a succession of piano players of different ages appear to play pieces that remain strongly in his memory. In the end, Nakashima himself plays his beloved Moonlight Sonata.

Moonlight

(Dec. 2018 at Kyoto City Nishi Culture Hall “Westy”)

Photo: Kai Maetani

(*6) Pamilya

This stage work performed by a female Philippine caregiver who actually works at a special nursing home for the aged from the Philippines, includes her talking about the work at the welfare facility where she is employed and demonstrating the work on stage. The audience that comes to see the piece are reminded of images of people close to them, as well as the possibility that they themselves may someday be in such a position. The title “Pamilya” is Tagalog for family.

Pamilya

(Feb .2020 at Papio Be Room-Large Studio)

Photo: Akiko Tominaga

(Nov. 2011 at Theatre Green)

Photo: Ryohei Tomita

(Sep. 2012 at The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo-Special Exhibition Gallery)

Photo: Hideto Maezawa

Zeitgeber

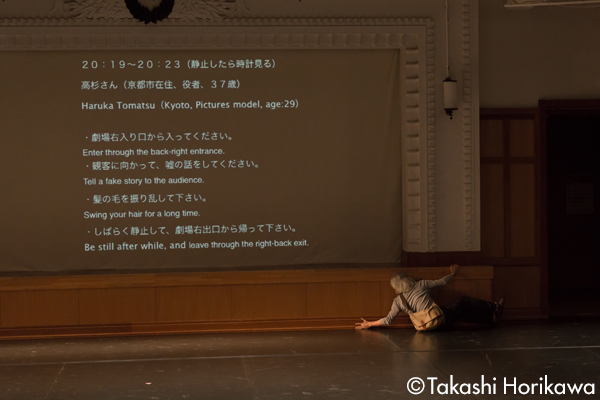

Everett Ghost Lines

(Oct. 2014 at Kyoto Art Center-Multi-purpose Hall)

Photo: Takashi Horikawa

Fools speak while wise men listen

(Mar. 2017 at Atelier Gekken)

Related Tags