Ability to dance denied during student days

- You are told that you entered Kyoto University of Art and Design in 2006 and studied in the Film and Stage Art department. Could we begin by asking you to tell us about your University years?

-

When I was a student, it was the last years that Shogo Ota (died 2007), known for his “silent plays,” was chair of the department. Among the professors in the department teaching dance-related classes were also Setsuko Yamada, Toru Iwashita, Osamu Jareo and Misako Terada. None of them were your usual professor types, and looking back I realize I was surrounded by a strange group of people! [laughs].

I had studied classical ballet from the age of three, and among the various lessons I took outside of school, I felt that I had worked at it pretty seriously, but I had never thought of doing dance for a living. Partly because both of my parents were teachers, I thought that after I graduated from university I would get a job like everyone else. But just out of curiosity I applied to Kyoto University of Art and Design (Kyoto University of the Arts from April 2020) and Osaka University of Arts.

When I applied for Kyoto University of Art and Design I took a “communication entrance exam” (A test of the applicants’ acceptability based on roughly two days of classes) and the student performance of Tadasu Takamine’s stage work Kaiba Q was a performance that was quite a shock for me. Other applicants were saying that it was really moving for them, but my reactions was, “I don’t understand what was going on,” and that is what I wrote in my report about it. The shocking experience I had in that communication exam made me decide to go to Kyoto University of Art and Design. In my first class, I listened to professor Ota talk on and on about the Universe and I had no idea what he was talking about [laughs]. So, at university I had the feeling that I was meeting really strange adults for the first time.

Throughout middle school and high school I was always the good student both at school and at home, but for some reason I was always good friends with the local nonconformists and the kids who dropped out of school and what was considered normal for a young person. For some reason it was easier for me to be with kids who were having a hard time being “normal.” I think it was because I saw these young people who were living in a different way from me as the “others” in my world. But when I got to college, I found that it was people who were by no means “normal” that were recognized by society and in positions as our teachers. I thought, “These people can’t be our teachers, can they?” [laughs] - So they were all very individualistic active artists, and among them was there any one who you were particularly influenced by?

-

I guess you would have to say it was Setsuko Yamada who had the biggest influence on me. Just because I had long studied ballet, she would never let me think that I had the technique to qualify as a dancer. If I was standing nicely in [ballet] form, she would say angrily, “Why are you standing like a dancer?” At the time, I thought that to dance was to raise your legs high and move around, so I had no idea why Setsuko-san was getting mad. During practice, she would shuffle over to me and say, “Who are you?” She would say with anger, “Why can you put on a face like a dancer and walk around here?” When it was a scene where I had to walk past dancers lying on the floor, she would say, “There are dead bodies lying here. How can you just walk past them unmoved?” So I would do what I thought she wanted me to do, but all the time saying to myself, “No, I’m me and lying there, that’s just [my friend] Saki-chan.” [Laughs] Now I understand that I was being asked how I should be standing in a given place and what it meant to be me. As I was taking that class, I began to dislike dancing beautifully, and I wanted to rid myself of all I had learned in classical ballet. Today I think it is good that I have a classic ballet background, but in those four years of college I hated it, and I even made a point to stand with bad posture.

One more thing that was an important experience in my college years was that from the second year I got an eating disorder for about five years. Eventually I was cured by hormonal therapy and I’m alright now, but throughout my college years it was very difficult for me to eat at all. In class I played the good student and created and performed works, but all the time my body was getting thinner and thinner. I almost never went out drinking with my friends, but everyone seemed to understand that that was just the way I was, and I was fortunate to have classmates that accepted me as I was. It was a time in my life when the me that was looked to with expectations for the works I created and the me that couldn’t eat and kept getting thinner switched back and forth violently. - What kinds of works did you create as a student?

-

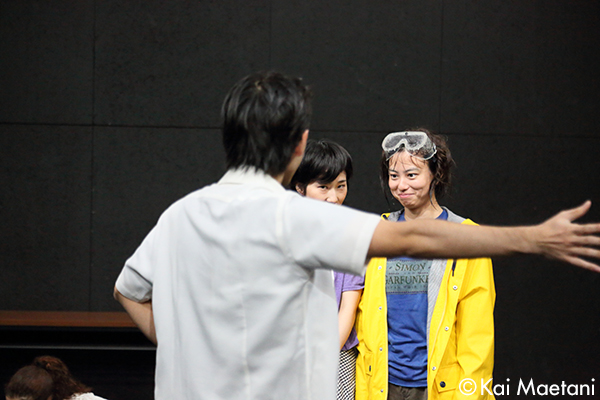

At the time, for the dances that I choreographed, I had friends in the same course as me perform them as they were choreographed. But from the piece “Sister Complex Syndrome” that I wrote in my second year, I changed to a style where I had the dancers interpret the choreography as they wanted. In “Sister Complex Syndrome” there was a scene where the dancers were supposed to kick my stomach again and again, and when I asked them to do it as I did, they couldn’t do it hard enough. From that experience I learned that getting the dancers to interpret the movement for themselves and letting them produce the movements in their own way resulted in stronger expression. After that I changed to a style that enabled them to be free of any consciousness of themselves as dancers and enabled them to express themselves naturally and I could then find interesting unique qualities of each dancer and choose who I wanted to work with in a given piece.

One example was a guy named genseiichi who was doing contemporary music in the Communication Design course. In one of the mandatory physical education classes that students from all the different courses had to take, I saw this gut who had a strange way of running and I went up to him and started talking to him and he turned out to be a really interesting guy so I recruited him to dance with us. After graduation he went to Germany, but now he is a member of the unit akakilike that I lead. My assistant director Naoyuki Hirasawa was in the video course of the same department as me, but he was the exact opposite from me, he wasn’t serious about college and didn’t come to school often, and I started working with him after being very strongly impressed by a piece he made in his first year in the course.

- Did you search for creators like that because you wanted to use music and video in your stages?

- It is all a question of whether I find the person interesting or not. There has been a case where I chose someone who happened to be doing video works, but it had nothing to do with the skills or the label. In the end, I think I am interested in people who are different from me. If I think a person is going to work, it usually works out OK. I know that by intuition, and I think that is the only area where I have genius. [Laughs]

- In addition to works for stage performances, from around the time you graduated you began presenting works that you called exhibits at galleries. In 2011, Kyoto University of Art and Design held the “artzone” event that set up galleries in the city and executed a work call “We’ll search for something at the end of the direction that you point.” You and a few others were permanently stationed at these “galleries” and all you did there was act as normal. There was no special space or movement so people who came there didn’t know what to do. [Laughs]

-

I concentrated on “exhibits” for four or five years after graduation. Looking back now, I see that period as a run up to what was to come. I had always thought that theater could never attain to real life. No matter how wonderful a work you might create, and how many people came to see it, it could never match the happiness of my parents when my sister showed them their first grandchild. And no matter how dramatic a time you might create on stage it could never match the shock of seeing a person’s throat cut and then die. And once I realized that when there are terrible things that actually happen, when it is something that makes you cry, that is something that theater can’t do, I decided that I wanted for myself and for the people with me to try and shorten the distance between reality and fiction.

The instructions that I gave the performers in those “exhibits” were to just stay there in the galleries from the time they opened at 13:00 until they closed at 20:00. And I told them that I wanted them to be aware of who they really are and to be conscious of what kind of person they wanted to be seen as. There was one person who just kept boiling beans, and another who had a musical instrument and was touching it and playing it, but since I am a dancer, I did dance movement at times. - Is it a matter of being able to answer with conviction when you are asked what [kind of person] you are, or what you do?

-

That’s right. If a person promises to just be themselves for a full day, what will come out is not fiction but one’s natural self, one’s essence. At first it was just a request, a questioning that simple. When visitors come, how will you act, what words will you speak? Is going to the restroom fiction, or is it your true self. Where do you draw the boundary between true reality and fiction? The “exhibit” project took that form in an attempt to answer those kinds of questions. If you have something that is real, then you should be able to make fiction, and I want to see that line right at the edge between the two. There were some minor rules and some accidents were prepared, but basically I left it up to the performers who would be in the exhibits to make their own time and spend it that way throughout the duration. And when they are doing that, they will make that effort to be the same even when there are no visitors there. That’s why, after about a week of continuing the “exhibit,” we found all of the performers getting a little strange. When the project was over and they returned to the real world, they would suddenly feel things like, “What? Nobody is watching me.” It is hard to explain, but that is the kind of strange feelings all of them had.

I can’t explain it clearly, but I feel that that “exhibit” project time was an experience that helped make me more certain about what I wanted to do with my theater-making from then on. It is a base, a starting point that has very strongly influences the way I create works now. Involving oneself with people can be scary, can cause doubts and uncertainties, but when I find myself up against the difficulties of involvement with people, I feel that I always return to the things I was thinking about at that time. - I would like to ask you next about your recent work. Your 2017 work “Nice to Meet You, Good Day, Who Am I Today?” was written as part of the Kyoto Metropolitan program “Model Projects for Building a Society where Citizens Shine through the Arts and Culture.” It was performed in January 2018 at Kokyo-no-ie in Kyoto’s Higashi Kujo district and in February 2019 at Rohm Theater Kyoto.

- It started when Satoshi Ago (Artistic director at THEATER E9 KYOTO) asked me, “Don’t you have an interest in the elderly?” “Do you want to go to a home for the elderly?” Since I love my grandparents, I immediately answered, “I would like to go.” I didn’t even know at that time that it would be as part of a program by Kyoto City or that I would be sent to a home for the elderly as an artist in charge [laughs], and so I went to the home with Ago-san and his people. It was an institution with a lot of residents who suffered from dementia, and when I was observing one of the exercise sessions there, for some reason I broke out in tears. That day I sat by one of the elderly men and did the exercises with him. After that, Ago-san asked me if I wouldn’t like to make a performance work, and I answered that I thought I could probably make one that very day.

- The Higashi Kujo area of Kyoto is a place where immigrants from the Korean Peninsula settled in Taisho and Showa eras and it remains a multinational community today with a concentration of Korean-Japanese.

-

I had heard about the Higashi Kujo area, but I hadn’t really known what it was like there at the time. The offer came from the person in charge of the Kyoto City program, Makoto Kuratani, rather than anything about the community itself, but I knew I wanted to get involve with these people create something with people like the elderly woman singing a song in Korean at the home for the elderly. But once I had decided to do it, I discovered just how little I knew about the area’s history and the backgrounds of the people, so I got them to show me old films about it and listened to the people’s stories and such. At the same time, I wanted to see the old grandfather who had been in one of my stage performances, so I went to see him regularly at the Kokyo-no-ie facility. The more I got to know the people the more I learned about the area’s complicated past and the problems of the North and South Korean nationals living in Japan. For example, I learned that there are separate home for elderly South Korean nationals living in Japan and for North Korean nationals living in Japan.

However, I don’t take things like peace or war or such-and-such issues as subjects for my works. The only things I can turn into works are small things that happen around me. But, when I start to make a work someplace, I find there are always big problems that are pressing down on the individuals. So, when I was asked to do the program for Kyoto City, I told Kuratani clearly that I can only do works about relationships with individuals. I said I don’t do works from the standpoint of communities or the elderly or social welfare. - In the work [of yours] that I saw at Rohm Theatre Kyoto, most of the performers had no theater experience, they were just people who lived in the Higashi Kujo area. On the screen on stage there was video showing you chatting with elderly people and visiting various places in Higashi Kujo and of you involved in conversation by the river. On the stage was the elderly man (Shigeru Yamada) in a wheelchair and you just making casual conversation, and there was a double appearance by a 4th-generation Korean national woman living in Japan shown in a video talking in Japanese and also live on stage speaking in Japanese.

-

Yamada-san would always have forgotten me each time I visited him, so I always began with, “Nice to meet you.” When he was in our performances and would be taken back stage for a scene or two and then wheeled back on stage again, he would already have forgotten me [laughs]. Lately he seems to remember me vaguely, and when I go to the home to visit him, he greets me, “Oh … Hime, kita ka,” (Oh … So you’re here, my princess). If, I am getting people who are neither actors nor dancers to go out on the stage to perform, I can’t very well stand back where it’s safe, so I do the dancing that it is my responsibility to do. When I am introduced as a dancer in Higashi Kujo, the elderly men and women ask me to dance for them, and so I do. In truth that is something that is hard for me, but because it pleases the old folks so much, I do a pretty dance. But that pretty dancing I do for them is not what I do in my performance works.

I also had Chuna, a young woman in her 20s who is a 4th-generation Japan-resident Korean national, appear in my stages too. She is an employee at a home for the elderly that is different from the Kokyo-no-ie facility and one who had doubts about the appropriateness of having the government office do a program in Higashi Kujo. Chuna grew up in Japan, and she talked with me in Japanese while we drank at a pub about the gap she felt when she went to South Korea and couldn’t understand the language. In our stage performance we showed a video of her talking about that and at the same time we had her appear in person on stage and speak the Korean she had learned. And I, who doesn’t understand Korean, am listening to her. So there she was performing in the program she originally had doubts about, and there are these gaps and disconnections, and everyone is standing there together. - I was surprised to see Kuratani-san from the City Hall performing with his own children. I was also impressed by the exchange between the man called Ura-chan and Kuratani-san.

-

Kuratani-san is interesting. He is a serious, hard-working man, but at home he is an adoring father. But his work keeps him so busy, and though he is in charge of Social Inclusion he doesn’t have much time to spend with his own family. I liked that gap, so I asked him to talk about the different faces I saw in him, not as city public servant or as a father but the various things I has seen in him as just a man. In the first performance, it was just Kuratani-san alone, but when we performed at Rohm Theatre Kyoto I had him bring his two daughters to perform with him. They just kicked a soccer ball around the whole time, but when he was with his children I could see him there as his essential self.

Ura-chan is one who always called me when he was going Higashi Kujo, and he ignored any pretense his label of being an actor sent by Kyoto City and we became friends who could say that we trusted in each other. He was always drunk, so often he would be talking on a different plane from me, but we did things like riding a double seated bicycle together [Laughs]. - It was a work that made quite heavy use of video.

- The video was filmed by my directing assistant, Hirasawa-san. When it became evident that it wouldn’t be complete with just what was happening on stage, I thought it would be necessary to add things that I saw and encounters I had in Higashi Kujo as seen from my viewpoint. I was born as a Japanese, and I don’t live in Higashi Kujo, so there is nothing that I can give opinions about. So it is just video containing the “views” I see of the scenery and the people I meet. No matter what I might try to say about the relationships between individuals and myself, it will always the community and its history hanging in the background. So I used a creative process with video to keep that fact from being hidden as well.

- The performances at the home for the elderly was sponsored by Kyoto City, but the one at Rohm Theatre Kyoto was produced by akakilike.

- That made a big difference for me. Because instead of doing it as a program of Kyoto municipality, I wanted it to be a proper work to be performed by our company. Although there are a variety of labels put on people, like 1st-generation Korean nationals living in Japan or 4th-generation, or City Hall public servants, more than that, I wanted a situation where I could decide, “This is a person I want to work with.” In the akakilike production, in order to make it clearer that the validity of the work was built on the individual relationships of the people appearing in it, I chose to have Kuratani-san’s children and Ura-chan perform in it.

- In September 2019 you presented a work with a title that read “Like the summer sea glittering with so many fun things that it is a waste to spend time sleeping, like a green garden flooded with sunlight, like a sky spreading to infinity so clear and blue as to drive you crazy.” It was a work that you created with people living at the Kyoto DARC drug addiction rehabilitation center. What brought about your encounter with Kyoto DARC?

- It was something that originated in Higashi Kujo. It was when we were helping to clean up rubbish along the river in the Higashi Kujo district that this group of men with a very powerful presence came and silently set to work cleaning up, then eating curry and smoking cigarettes after that with there pocket ash-pouches in hand. I was wondering who they were and then I noticed the words Kyoto DARC on the breast of their work uniforms. Then I couldn’t help but follow them and told them that I was making stage productions and I would be happy if they could become involved in some way. Apparently they thought that I wanted to enter the rehabilitation program and one of the staff members invited me to come and sit in on one of our meetings as an observer.

- Did you follow them because you felt some sort of appeal in them?

- At that time I happened to be in the middle of working on a performance work titled Sabaku (literally passing judgement on a criminal, etc.). The cast was 10 male dancers and one woman, and I wanted to express the threatening aspect of male a collective but it was still lacking in its sense of oppressiveness or intimidation. When I saw the group of men from DARC, I intuitively thought, “This is it!” So I invited them to come to our rehearsal studio. At first, I never thought I would end up doing a work with them, but in the process of visiting DARC meetings I found myself being attracted to the presence they each had and the way they were.

- What exactly was it that you felt when you were visiting DARC?

-

At DARC, they had sessions they called meetings three times a day and they were given a subject or theme to talk about themselves from. The basic rule is speaking when and what you want and listening to what you want to hear, but never giving opinions about what others say. The first time I visited DARC, I sat in on one of those meetings. Since I was not a DARC resident I couldn’t take part in the meeting, but as I sat quietly off to the side listening, I felt that what I was seeing and hearing could constitute a finished work just as it was. I think that at first they must have been very suspicious of me, but I kept going there once a week when I had time. And in the process of that, we got the mutual feeling that there was nothing to fear in each other, and eventually it got to the point that they were waiting to see me. At first I was just going to the morning meetings, but in time I would stay on and make lunch and eat with them, then hang out for a while until it was time for the noon meeting, then hand out some more until it was time for the afternoon meeting. And since they never told me it was time I should be going or said, “Get out,” I would end up being there all day like that.

It kept visiting weekly for about a year and a half, so I had plenty of time to judge what kinds of people they were. I didn’t really keep going there because I intended to create a work about them, but as I listened to them and watched them, I would get images of how a certain person among them would have a place in a certain film setting, or I would find myself thinking that this particular person is not good at talking but everything he says is true, or that another person is good at talking because he has been in DARC a long time. So in that way, I found myself naturally visualizing how each one of them would fit into a certain scene in a stage work. - I think putting on a performance in a facility that is just for the facilities residents or friends and putting on a performance at a public theater or the like and selling tickets for the performance are two very different things. How did the people at DARC feel about the performance?

- I first told the director of the [DARC] center and the people in rehabilitation there that I wanted to make a stage that people would pay to come and see. It wouldn’t be like a an exchange event but a proper performance of one of my works that we would ask people to pay to see, like they do for my other works. I immediately got the answer, “We don’t know much about theater, but if you say it will be a good work, Kurata-san, then OK, we’ll do as you say.” I think they trusted me because I had been involved with them already for such a long time. For them, a year and a half is an incredibly long time, enough for drastic change to take place, time enough to enter and leave DARC and for big change to take place between them and their families. Half of the people at DARC at that point had been there a shorter time than I had been visiting DARC. When we did our opening performance and they got applause from the audience after it, I think that was the first understood that it had indeed been a real stage work. Until that, I think they had surely been dubious about it.

- Your work “Like the summer sea glittering with so many fun things that it is a waste to spend time sleeping …” begins like a scene from a press conference. Seats are lined up the full length of a long table and the DARC people are sitting there and their role is answering questions from the audience in the conference room. And from the content of the questions we understand that it is a scene where local citizens are protesting the opening of a drug addiction rehabilitation center.

- There was a protect movement that occurred in a district where Kyoto DARC was planning to open a new center and at that time there actually was a town meeting to explain the project to the citizens. I myself was in attendance at that meeting and I saw the citizens asking some very harsh questions. But the member of DARC kept their calm and answered the questions meticulously with confidence and in a thoughtful manner. So, I was able to have a clear image of how they would act on stage and how they would speak if I just set that situation and the questions that would be asked, and I was confident that it could be done as a viable stage. So, there was no stage script for that scene, and sat up there on stage along with them and thought about how I would answer those harsh questions and said what I thought naturally.

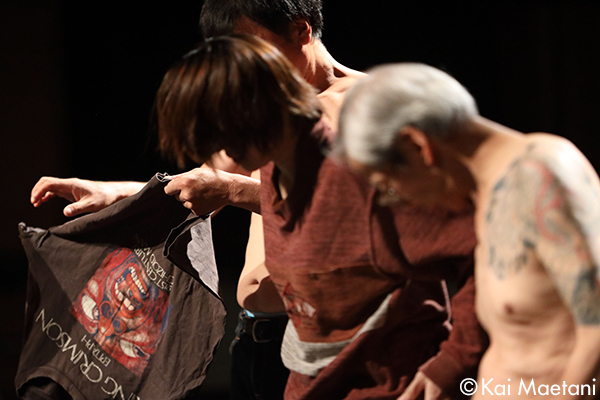

- After that, you and all the others took off everything but your underwear. Then we saw that there were some who carried vivid tattoos. Then you all prepared a meal together and each talked about their lives and other things, just like they did in their daily life at DARC.

- People who know the situation at centers like DARC also know that it was exactly how they spent their days. I told them in the rehearsals that they should just talk like they do in their daily meetings and I didn’t write out any kind of words for them to speak in a stage script. That said, however, because they are people who don’t perform on stage, there was some nervousness and their words did sometimes sound like they were reciting lines, but even so, none of it was lies, and I didn’t tell them to try to speak more naturally either. I was not trying to say that these were people who have problems getting by in society, nor was I really trying to say that these are good people at heart. Those are not things that I am in a position to say, so I just wanted them to be there on stage as they are, as their natural selves.

- You accepted them as they are and you let them spend the time [on stage] as they normally do. I think that your doing it this way is different from what other stage directors have done until now. At times, the position of the director is a strong one and one that uses the performers to express the ideas that the director has in mind. But I feel that you deliberately place yourself in the same weak position as the actors, and that [equal] relationship is the only one you try to project.

-

I see myself as a very weak person. When I had an eating disorder in my college days, at school I played the good student Midori Kurata who was always working hard and turning out impressive work, but when I went home I was a like a small child who just sat in front of the television eating snacks and watching children’s programs. I got though those years by changing back and forth between those two personalities. Lately, life isn’t that hard for me anymore, but I still have that weak side of me in place and together with the stronger me I am one person. You could say that I have gotten better at acting the strong me.

I think I owe a lot of my ability to be this way to the training that Setsuko [Yamada]-san put me through in my days at university. It was not with regard to dance but the way she taught me that just because I was a dancer didn’t mean I could get by without being able to talk. In my first year at university, when I tried to say what I really felt, I would always start crying. But she wouldn’t let me get away with that. She was very firm about making me put the things that I felt into words and forcing me to speak articulately. That is why, conversely, I became able to recognize the weak me and accept it as me.

Listening to the people at DARC talk, I sometimes find myself thinking, “That’s me.” That doesn’t mean that I just understand what they are saying. I don’t pretend that I can easily understand what these people who have experienced such horrible things as them went through, but there are moments when I feel like they are talking about me. However, I don’t want the say that I am able to share their feelings …. - I use the word resonance in that kind of case where I feel a connection, but within the scope of my own personal context. There is that kind of feeling, isn’t there?

-

That’s right! There is that kind of feeling of resonance. A man who I trust very much, the facility director at DARC, brought his child along when he came to see our performance of this work. He told me, “I thought about where we are headed, but my conclusion was that I don’t think we need to be headed anywhere. There is just the fact that we got to know you, Kurata-san, and I feel that if there is anything that we should value and care for, it is simply that encounter. So, I think it is OK if you do what you think you should.” That was very encouraging, and it gave me the courage to go on.

But sometime later, when I talked to him again, he said, “It may be disrespectful to say this, but you have something in common with us at DARC. That is why you understand us and can see our good sides, but we also have another side, and it is a very scary side of us. ” Then he went on to tell me, “I believe that you have the strength to accept that other side of us, but that is something that you must never do.”

I don’t pretend that putting the DARC people on stage is contributing to their recovery, I just thought wanted to have them on be there on stage for me because of the very cool presence they have, and that they should be there as they are. To be truthful, DARC is indeed a tough place to be. When we did the scene where we prepare a meal, a locked briefcase was brought out from the staff room and it was unlocked to get out the cooking knives, and that is actually how it is done at DARC too. It is to make sure that knives are not around to be used when something happens. I know there is that danger. And I keep asking myself if I want to continue being with them nonetheless. - In documentary theater works I often sense behavior that seems to be deliberate efforts to make it work as theater or to make it look like a viable work of theater, but strangely, for some reason I don’t find that in your works at all.

- It makes me very pleased to hear you say that. I am always tremendously careful not to let my works become that type of documentary theater in which the director is exploiting the subjects to some degree in order to make the work look like theater. Nonetheless, when looked at by people from the outside, it may have some of that look of exploitation, but still knowing that, in my case my desire to work with the [DARC] people because of who they are came first. I myself took my clothes off with them and went to the very edge to make theater that is [borderline] fiction.

- I would like to ask you now about dance, where your roots originally lie.

- I think of myself as a dancer. Many dancers like dancing connect to dancing emotionally, saying it is “fun” or “it feels good.” But in my case, perhaps because of the influence of Setsuko [Yamada]-san, I connect to dance as something hard. When I am working with dancers in the rehearsal studio, I often tell them not to take the choreography and make it into movement that makes them feel good. If that is the premise, then what is dance? For me, dance is not like a matter of using the body’s functional potential to the fullest to show beautiful movement or forms like in classical ballet, instead it became a process of pursuing something to the limit. In the case of Setsuko-san, she could just move her fingertips and it became dance, but I can’t let myself do the same thing. Sometimes I think that if I had the kind of strength and intensity to create dance as her, maybe I wouldn’t even need to dance anymore. To me, dance is the way you think about things, what basis you have for what you do and being able to stand on stage in complete honesty. This is a hard thing to communicate to the other performers. It is hard for me to put in words, but said in one extreme, it is not about choreography at all.

- If your dance is the basis for being alive on stage and something that shows a person’s way of life, that means that you have to look at each performer’s life and each performer must in turn look at their own life.

- Yes, it come down to that. After the performance work I did with the people at DARC, I created a work primarily for young dancers titled “Tomorrow everything ends, so now let’s talk about the worse things we have done until now land.” They were young men and women who have been dancing since they were little, so their skill level was quite high and they all said that they liked dance. But in some sense they all leave their life behind and enter a different world when they are on stage. At times, dance and the stage can be a place to escape from everyday life, a place to free oneself. When I am creating a work with dancers like that, I have to work very carefully. Because it may change the way they approach dance, or even the way they approach their lives. But, because they are all strong, in the end, even if I tell a dancer in rehearsal not to do something, some will still go ahead and do it in the final performance. That may be the last time I ever work with a person like that, but all I can say is, “Well, that’s because it’s the true you.”

- Why do you think that you go to such lengths and make such efforts to create works based on the relationships you build with others.

- I believe it is because I can only know myself in the context of relationships with others. That is why I have no interest in doing solo works. And it is especially difficult lately, because a lot of the productions I am doing now involve large groups [laughs]. The contact with various different people’s lifestyles and the way they think lead to clearer understanding of myself, and it brings realizations about how I perceive things and how I respond emotionally in situation. In the end, what concerns me isn’t whether or not a person finds life difficult, what I want to see is how a person reacts, what is revealed about a person when involved in a relationship. So, in my works, someone is always watching someone else. By setting situation based on another person’s perspective, I keep myself from falling into a state of self-satisfaction or complacency. Having a lot of people, and many of them strangers, increases the chances of interesting changes occurring in our perspectives. And a prime factor that determines the way I fit myself into a diverse group of people may be their intensity and strength.

- There has long been cases of people with talent who are able to express their own worldview and win the world’s attention, but today I think we are seeing a trend in which it is not just who creates works but what new worlds are revealed depending on who an artist chooses to work with. I believe that you are an artist who is practicing this new type of art based on who you work with, but at the same time this puts a whole new responsibility and pressure on the artists who work this way. Aren’t there times when it is hard to maintain a manageable distance between the individual artists working together this way? Is it that the fact that finally showing the finished work to an audience gives you a buffer of some sort?

- I do it with an awareness of the risk. But if I didn’t have that willingness to take risks I don’t think I would be able to work together with people to create works. That is why, basically, I can only create works as I am. It was the case at Higashi Kujo and with DARC and when I work with dancers, I can only work in the context of individual relationships between myself and each of the participants. Although it is certainly true that when presenting the productions are performance works, it is often a very fine line between success and failure.

- Now I would like to ask you about some of the specifics of your working process. You are not the leader of a [dance/theater] company but of the unit “akakilike” made up solely of technical staff members.

- From my university days, I presented the works I directed as akakilike productions. That name was something chosen rather spontaneously when talking with dancers and friends. At the time {with my eating disorder} I couldn’t eat things that were red, like strawberries, tomatoes and beef. And friends told me that, in the end, weren’t the things I liked and disliked were merely two sides of the same things, and they came up with a name made up of the Japanese for red (aka) and the Japanese for dislike (kilai) and like, which added up to “akakilike.” I thought it was a pretty good way to sum me up. After graduation I didn’t use it though and presented works under my name Midori Kurata, but from 2016, when we were doing projects as a team, I decided to use the name akakilike. But, I am still always embarrassed went people ask the origin of that name [Laughs].

- What kinds of people are your akakilike members?

- Rather than a format where there are staff members that work for the dancers and director, I wanted to work on equal footing with a group of creators, so that is what I put out a call for. And I was pleasantly surprised to get a full staff come together, including sound and lighting people, directing assistants, stage art, publicity, and advertising and production people. Among them were some I have mentioned earlier who were working with me from my university days. For projects of the type and size that akakilike does, usually the technical staff gets a salary, but the dancers and actors are not paid. But I wanted to work in a format where everyone is on equal footing and we are able to do projects because we have a staff that accepted that approach from the beginning. Even in that format we are able to function because everyone trusts in the work we are doing. So, the scariest thing for me is the opinions of the staff.

- The cast is different for every project. Do you have something like a methodology or working process for taking a project concept and working it up into a finished work for performance?

- Once I get an idea of what a person is like, I am able to see intuitively how they should fit into a stage work. Of course, some people are good at hiding their true self, so often the process takes time. In many cases, the contents when we first start out working the studio work will end up being very similar to the final performance stage. When I looked back over of the video recordings of the work “Tomorrow everything ends, so …” that I created together with the dancers, I was surprised to find that what we were doing in the early studio rehearsal stage was almost exactly the same as the final opening performance. The soundtrack that we had rather arbitrarily chosen to start working with in the studio ended up being the one that we used in the final performances. So, the work process tends to be one of gradually building the intensity of what we started out with. In the studio work I focus on finding the basis for a performer to be on stage and then work to strengthen that fundamental base. With the re-staging of our work A Family Photo that we performed in Yokohama in February, I had an insurance salesman who came to me to be a very interesting person, and created that work based on him. Even before we started the studio work, I already had the whole composition in my head down to a lot of the fine details. And in cases like the stage director Jun Tsutsui, who perfectly fit the image that I had in mind of the family’s father in the composition I had in mind, from the very beginning I had visions of who would work perfectly in what roles. So, there are sometimes cases like that.

- At that time in the creative process do you have the movements all visualized in your mind too?

- If I have dancers that I trust, I can imagine how they will move after I give them some instructions, and after that I leave it up to them. Because they are people who can play out a part once I give it to them.

- Do you write out dance notation or text specifying the overall movements in a work?

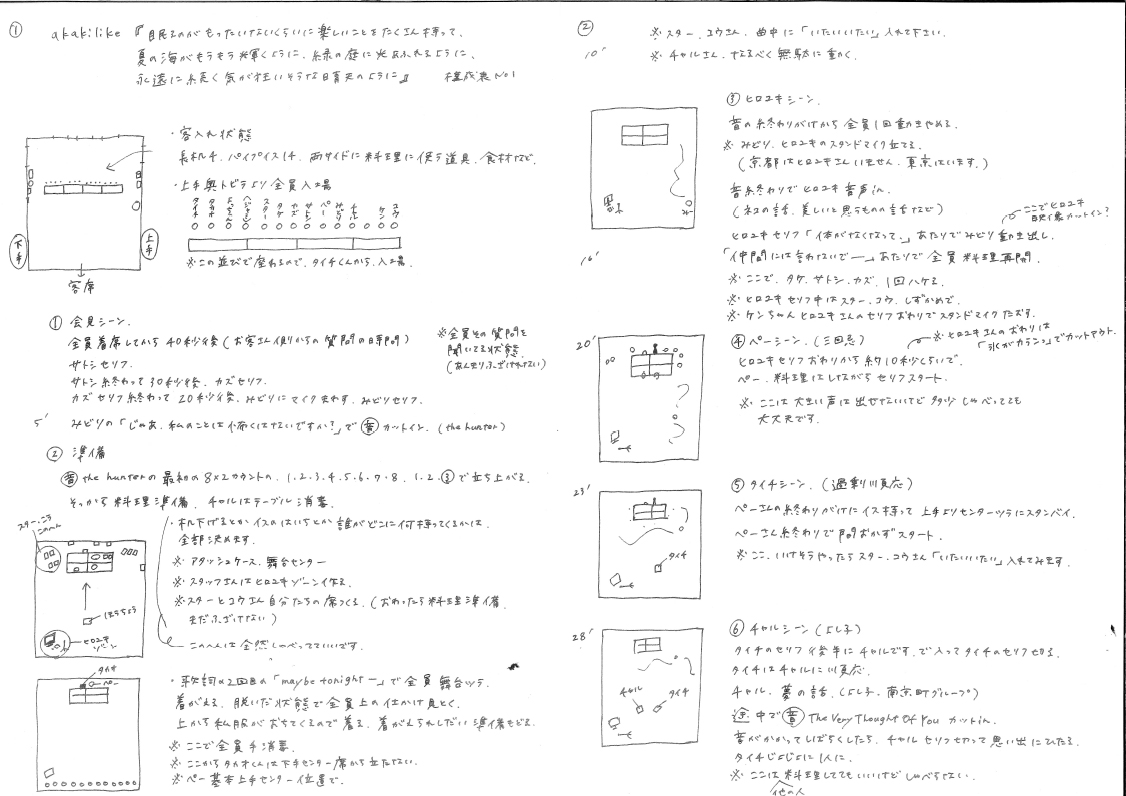

- I always do a handwritten composition diagrams. For the dancers and my staff it is always a rather rough diagram, but in the case of the project with the DARC people, I did quite a detailed composition text/diagram.

- Can you show us one. I see it is full of quite detailed instructions. At what stage in the creative process do you make these?

- Sometimes the notation is sparse and written early on, and at times there isn’t enough time to write a full notation. In the case of the DARC people, since they aren’t people who are used to being on stage as performers, I wrote everything in some detail, and when changes were made I got everyone together to stand in front of them and give a thorough explanation. Now that you mention it, Setsuko-san also used to write out a director’s instruction sheet similar to a composition text/diagram for our performances of the stages we created in class, so that may be why I thought it was the common way of doing things.

- Among the titles of your works are long one like sentences, aren’t there?

- I recently discovered why I do that. The works with short titles like Sabaku and A Family Photo are works that are either about me or have a clear theme and the composition is clearly decided from the beginning. But the long titles like “Nice to Meet You, Good Day, Who Am I Today?” that we did at Higashi Kujo and “Like the summer sea glittering with so many fun things that it is a waste to spend time sleeping, like a green garden flooded with sunlight, like a sky spreading to infinity so clear and blue as to drive you crazy” are also about me, but at the same time the ones that bring in other people and the presence of those other people can possibly effect a change on me. It is works like these where the titles get long. So, I realized that when I am doing a work with other people, the contents can’t be sufficiently explained in a short title.

- I think I understand now that if your process based on “Who do you work with?” is going to be brought into the title, it becomes long of necessity.

- The title of the work “Like the summer sea glittering with so many fun things that it is a waste to spend time sleeping …” is one I think of as a good title. It is hard to explain to someone who hasn’t experienced the atmosphere at DARC, but the residents there are normally bright in their manner, laugh easily at the slightest of things and seem to be enjoying themselves. And although it is hard to explain, there is also a heavy parallel time dimension there where they feel like they are suffocating. It is not depressing. But the shadow of death always seems to be lingering nearby.

- In 2020 you will be having more productions at big theaters, won’t you?

-

This year I decided to take on a lot of things. Since early on I have thought that [creating] works is not a business, and I also had my doubts about competitions where you had a limit like 30 minutes to come up with a piece. I had always worked stubbornly to not be consumed within limits like that, but this year I have decided to try working with big organizations.

*Due to the coronavirus crisis, there have been big changes in the original theater plans.