A new endeavor with Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

- In recent years you have been active creating dance works on commission from the New National Theater, Tokyo and the Kanagawa Arts Theatre (KAAT) that can be appreciated by a wide demographic from young children to adults. This year, two of these works of yours were re-staged, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Circus , and of these, the Alice production toured to 17 cities around Japan. I had seen the premiere of this production and it starred some first-line dance artists including Tomohiko Tsujimoto and Yasutake Shimaji, who at first appearance may look rather imposing or even ominous, but once they start dancing they deliver awesome performances. Seeing adults like them perform must be a very rare experience for the children as well as adults who are not used to seeing dance. The audience delighted at the performance of Ayaka Hikima, with her flexible body gained from her initial career in rhythmic gymnastics. The comical depiction of the Queen of Hearts by the highly unique dancer and choreographer and Naomi Shimotsukasa was another highlight of the production. All in all, it was a work that came to life through such highly unique and even eccentric performances.

-

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

was a work commissioned for the Kanagawa Arts Theatre (KAAT) “Kids Program” and the artistic director Akira Shirai asked me to make it a dance work that included a strong theatrical element. Its tour lasted for about two months, which I believe is quite rare for contemporary dance productions in Japan. I believe this program was probably made possible because it was based on a production policy of devoting the first year to creation and the second year to putting together a tour. I had previously worked with Shirai-san on a variety of projects, and he offered me advice on numerous occasions. We chose the actress Maria for the lead role of Alice by audition for the first time. She was still in high school and it was her first major role for the stage. What impressed me most of all at the audition was her radiant brightness of personality and her cute appearance. There was of course some risk involved in using an unproven performer like her, but if you don’t attempt to use people with unknown talent at times, there is a danger of ending up with a production that is confined to the usual and only gets more ordinary from there.

- You usually have original music composed for most of your pieces, and for Alice the music was by the composer Junichi Matsumoto, who is known also music for movies like director Kore-eda’s Soshite Chichi ni Naru (Like Father, Like Son).

- I have an aversion to just putting on a CD and dancing to it, and when it comes to creating my own works, I can’t see the sense in bringing into it music that already exists and has a world of its own that it was created for. When I was young, I hated being confined by sound, and I also dislike being forced to follow a consistent rhythm; I came to think that dance didn’t need music. Well, perhaps it is just part of a hidden jealousy toward music, or more probably that I’m just bad at keeping a beat (laughs). Of course, now I sometimes use classical music pieces, and I understand the relationship between music and the human body, but I still have a strong preference for live performances and original music. The core that Matsumoto-san builds much of his music around is beautifully sensitive melodies, but also works in a wide range of genres, from large-scale orchestra works to pop music, and he also creates works that are rich in imagery. Kodue Hibino is a costume designer that I have been working with for a long time, and once again this time her costumes created a unique world of their own such as I had never seen before.

- Naoyuki Miura, leader of the theater company LOLO, collaborated on the stage script. You have performed in numerous theater productions (*), but I don’t think you have ever done a work of your own with a script with so many spoken parts, have you?

- Well, I began my career performing in musicals, so I had no aversion to having spoken lines in a performance. But when I was young I had poor enunciation, and I had a rather low voice that was a mismatch for my baby face, so I didn’t like to talk much. And of course, I didn’t have the kind of voice delivery that was good for musicals (laughs). I have to admit that the reason I went into dance was not only because of the appeal that dance had for me but also in part because it was a way to avoid words.

Beginnings in “Ongaku-za Musicals”

- Please tell us about your initial encounter in Ongaku-za Musicals. The Ongaku-za Musicals was started in 1987 and became very popular for championing original Japanese musical productions (Its predecessor, Theater Company Ongaku-za was founded in 1977. Ongaku-za Musicals was disbanded in 1996).

- I joined them two years before Ongaku-za Musicals closed down, at the time when they were most popular. At the time I had no interest at all in the performing arts, but my brother was a visiting instructor in apparatus gymnastics for Ongaku-za Musicals, and that was the only reason I first went to see a performance. I was a student of international business management at Obirin University, and I just didn’t have any interest in the courses I was taking. Today, Obirin University has a popular dance department centered around Kuniko Kisanuki, but when I was there it had nothing like that, so I had lost any sense of direction. Seeing me that way, my brother gave me a ticket to see one of Ongaku-za’s most popular musicals, Mademoiselle Mozart . It was really marvelous, and as I watched the performance on stage, it was like looking at my own life.After that I just couldn’t contain myself, so I auditioned to join the company the next year as a study intern. I didn’t even know what an audition meant, but I decided I had to do something to make an impression, so I shaved my eyebrows and waxed my hair to stand straight up (laughs). I tried to show I could do a back flip but hurt my ankle and had to crawl off stage, but I passed the audition!

- Did you begin dance after joining Ongaku-za?

- Until high school I did things like apparatus gymnastics and soccer, but I didn’t have any special experience in dance. From my first year as a study intern until I became a trainee, I had lessons all day long, and I also went to the open dance classes in the evenings. I did everything I could to train my body as rigorously as I could. If it wasn’t for this period, I wouldn’t be what I am today. During meals I would be stretching the soles of my feet, on the train I would be loosening up my shoulders, while lying down I would loosening up my ankles, my daily life was dedicated to stretching exercises. I knew that after the audition I wouldn’t have time to go to classes at the university, so I resigned from the university after to audition.

- Since your start was not in dance school but in the musical theater company, it must have given you the opportunity to learn about a wide range of performing arts, didn’t it?

- Yes, it did. That was really a good thing for me, I feel. In my second year I was able to appear in the company’s stage performances even though I was still a trainee, but that was just before the company disbanded. I became one of the founding members of the new company STEPS that was formed by former Ongaku-za members, but I ended up leaving that group after two years, finally deciding to focus fully on dance. After entering Ongaku-za at 21 and beginning dance there, I was 27 when I gave my first solo dance performance titled YŪZURU , and the six years in between had really been an intense period of learning and training. During that time I had the good fortune to experience, singing, acting and the backstage theater arts.

- Was there something in particular that prompted the decision to become a dance artist?

- It may sound like a strange story, but at the time of the last Ongaku-za stage production, I was sick in bed with a terrible cold and at that time I had something that you might call an out-of-body experience; anyway it was overcome by a very strange sensation. I had a very clear feeling of the existence of things subject to gravity and things that were not. The next day, when I was still feeling faint from my illness, I began to search for the substance behind that strange physical sensation I had just experienced of something like “a sense of things that can’t be felt” or “things that feel like they have substance even though they don’t.” And when I did, I had a physical sensation I had never had before in dance, and it made me completely absorbed in dance. Since then, the origins of what make me continue to pursue dance are the undying fascination with questions about the perception of “things that appear to have substance but don’t” or “the state between things that exist and things that don’t.”

The Encounter with Contemporary Dance

- After the break-up of Ongaku-za, what genre or world of dance did you go into?

- Since I has started out in musicals, I didn’t know anything about the world of dance or its history, and to people in the dance world I seemed to be a mysterious entity that made them want to ask, “Where did this guy come from? (Laughs) As for me, I was thinking hard about the question of how I could make a life for myself in dance. The person I met at that time was Kaoruco, of the same agency I still belong to. She is someone who not only became very successful in the business of choreography for TV commercials and idols but also creates dance works of her own. Having known her from the work she did with Ongaku-za and STEPS, I was fortunate to be invited by her to dance the lead in the work MANDALA (1997).

- When you performed the scaled-up version of that work, SHINLA – Wind Blowing through Universe (co-direction, choreography by Kaoruco and Kaiji Moriyama) at the 2001 Edinburgh Festival, the local newspaper called you as “ One of the most talented dancers at this year.”

- Yes. That was a time when I shaved my head and dyed my eyebrows and took lessons all day long at the dance studio. I was getting invitations to dance with artists like Yoko Ando, Kota Yamazaki, Aki Nagatani and Yukio Ueshima and I was gradually beginning to build connections in the contemporary dance world. I dance with Ryohei Kondo of Condors in the piece Chinoise Flower choreographed by Yamazaki-san.

- Ando-san went on to become a dancer with the Forsythe Company and Yamazaki-san eventually won the Bessie Award. Yamazaki especially became a star in his own right with his new style of dance for male dancers combining Butoh and ballet. Chinoise Flower was one of his representative works and you stood out, to the attention of many in the dance world, including myself, for your exceptional presence. Then in 2001, you presented your work YŪZURU . Is this a work that takes as its subject the Japanese folktale Tsuru no Ongaeshi (The Grateful Crane)?

- Yes. I chose this story, about a crane who takes human form in order to return and repay its debt of gratitude to the man who had rescued it from a trap, because it has an aspect of the theme I mentioned earlier that I have long been drawn to of “things that appear to have substance but don’t” or “the state between things that exist and things that don’t.” And the idea of turning Noh works into dance connects to that. The characters that appear in Noh plays are primarily the ghosts of people that have died. The splendid costumes and the fact that the characters are presences that don’t actually exist in the here-and-now are thing that fit my aesthetic sensitivities. Of course, part of the appeal of dance is the vitality and flying sweat of the body, but I don’t want to limit it to that.

Collaborations with the Noh artist Reijiro Tsumura

- Another core of your activities is your collaborative work with the Noh artist Reijiro Tsumura (Kanze School Shite role Noh artist. Also participates in many contemporary works with artists from other genres). I believe your first work performed with Reijiro was YOROBOSHI (2003). Would you tell us how the two of you met in the first place? The Noh play YOROBOSHI is about a father who has driven his son out of their home on what turn out to be false charges and happens to meet is son later after he has become a blind beggar, known as Yoroboshi. Seeing his cherishing the scent of the plum blossoms that have fallen on hid sleeve his father encourages him to do the Jisso-kan meditation (to envision the Land of Nirvana, but the scene that come to his mind makes him delirious.

- It all began when I performed “Maihime to Bokushin-tachi no Gogo” (Afternoon of Fauns and Nymphs) (2003) duo dance series with Kaori Kagaya-san in the New National Theatre, Tokyo. At the time, I had become interested in Noh due to the influence of some friends. And, for some reason, the character “ Kaori ” (fragrance) from Kaori-san’s name sparked in me an association with fragrance of plum blossoms, which led to my learning about the Noh play YOROBOSHI . That association with flowers in turn led me to an image of a worldview or view of life for which I created the composite word Kasoukan (combining the characters for flower thought and worldview). At the time I was thinking of a duo piece with myself dancing the role of Yoroboshi and Kagaya-san the role of Umenosei (Spirit of the Plum Blossoms) and I was looking for someone who could compose a Noh piece ( ji-utai /chant). Then, when the photographer Toshiro Morita, who is very knowledgeable about the traditional Japanese arts invited me to see a Takigi Noh (open air Noh performance) performance by torch-fire light, and after the performance he took me backstage to meet the main actor, [Reijiro] Tsumura-sensei. That was something I hadn’t expected, and I was standing there with my hair dyed yellow and wearing short pants. I said, “I want to do a dance version of YOROBOSHI and I wonder if you would collaborate with us.” Then Tsumura-sensei immediately replied, “Oh …. That would be good.”

- In other words, you suddenly got the opportunity to do collaborative creative work with one of the big names in the Noh world who is more than old enough to be your father. (Laughs) Didn’t this encounter with Tsumura-san become a big thing for you?

-

Very big, indeed. It was also the door to my deepening encounter with Noh, and it was something that prompted me to think about my spirituality and physicality as a Japanese and about my own identity. And, more than anything, it taught me about the mind and soul to approach dance with. At the time, when I danced it often led me to a somewhat dangerous state of mind. For example, when doing improvisational dance on stage, I would feel an insuppressible destructive urge rising within me. I would ask myself if it was OK to go wild, or I’d wonder if I could suppress it or if I was going to go crazy. It worried me to the point that it bordered on a phobia. After I met Tsumura-sensei, he taught me that in Noh the word kurui (insanity) effectively meant to act (perform), and that it also meant to dance. Once I knew that in Noh performance was spoken of intentionally “going crazy” and to show that as a performance on stage, I gradually became able to stay in control as I danced. I felt like I had been saved. That led me to create the work titled Kuruisourou (2009), meaning “Shall we show you what insanity is.”Because Noh is a traditional art, there are strict rules about things that you are forbidden to do, but whatever I asked Tsumura-sensei to do, he always says kindly and willingly, “Let’s try it.” That is why I was able to do things that I wanted to try. Tsumura-sensei wasn’t born into a Noh family but started Noh from his college years, and what’s more, his teacher was the female Noh artist Kimiko Tsumura. Thus he inherited and has carried on the thoughts and spirit of Kimiko-san, a woman who spent her whole career working creatively in the traditionally male world of Noh. What’s more, because he entered the Noh world from the outside [rather than being born into it] he has always been tolerant and accepting, and that is why to this day I have the greatest respect for him and deep gratitude for what he has done for me.

- Since you also came into dance not from the usual path of starting ballet lessons as a child but rather by tremendous effort from a later age to win a place for yourself in the dance world, you have much in common with Tsumura-san. But I have to say, I was really surprised by the duo piece OKINA you perform with Tsumura-san in the New National Theatre’s DANCE EXHIBITION (2004). Tsumura-san even bared his torso [like you] for the performance. In the Noh world that would be impossible.

- It was truly a breakthrough that only youthful passion could have made possible. We are told that when a Noh artist is going to perform in a new project they have to file for official approval beforehand with the head of their family (school), but in this case Tsumura-sensei made a very discreet request to get approval for our project.

When I was young, we were determined to live with a rebellious spirit, breaking every taboo, and if we didn’t live that way and express ourselves through our efforts there was no meaning in doing dance. As you become adults you naturally become more cautious and cowardly, but Tsumura-sensei accepted and went along with my youthful passion.- The Noh work Okina that your piece OKINA takes as its subject is a prestigious work in a class by itself in the Noh repertory. Your presence had the appearance of one acting out the visions of Tsumura-san’s youth, in what was a stage performance with an incredibly tight-knit air to its development.

- Seen from the eyes of traditional Noh artists it might have seemed disrespectful, but before the performance I performed a Bekka ceremony to purify the mind and body. It was a stage that I could only perform after purifying myself.

Since I don’t do Noh movements, I tried to give expression to all kinds of things by moving my body like an insect or a rock, using all kinds of methods and objects. In contrast, Tsumura-sensei danced in the Noh manner using simple movements and a core state to express the myriad things of the natural world. We began by accentuating the presence of these two different bodies. Tsumura-sensei may become the center of the stage, he may define a whirlwind, or I my become a whirlwind. I wanted to have the two bodies battle within that relationship between them. And I thought that the state of conflict would become a form of prayer, of thanksgiving.- Did you study Noh or reciting of the chants?

- I began by taking lessons, but not so much with the intention of learning the art but as a means of finding approaches for myself to use on stage when dancing in juxtaposition to Tsumura-sensei. But there is no way I could move like a Noh artist and there would be no need to. Still, although there are differences in the way ballet training is used as a base for the discipline of dance and the words that are used as an approach to the things Tsumura-sensei places importance on in the discipline of Noh, I think the two are somehow linked. What I find interesting is looking at the clear difference and thinking about what they mean.

- Two years after OKINA you presented your new work KATANA in 2006. This was a work you created for a Showcase sponsored by the Japan Society in New York. And after that you put it together as one work. Where did the idea of using the body to express a sword come from?

- A big influence that sparked my interest in the sword was that, even though I had been struggling long and hard to learn the Western dance of Europe and America, I was in a period when I was also discovering a strong appreciation of the fine old traditions of the culture and arts of my native country Japan. I was asking myself what was Japanese culture and what was Japanese physical expression in the context of contemporary Japan, which had introduced not only Western lifestyles but also the European and American, the Western approach to expression and the changes it was undergoing. I wanted to be certain about my identity as a dancer.

Since olden times, the Japanese have valued methods of physical expression that invest spirituality and soul in “forms.” There are actions based on manners, ritual and courtesy, and it is the same with the traditional arts. And not only in movement but also in things like wonderful crafts and art made by minds trained and disciplined and finely with honed creative skills. Our Japanese ancestors have long excelled in the sensitivities and ability for expression that imbues “forms” with soul and spiritual meaning. Of course, today as well this proud Japanese tradition lives on, but it may be that some parts of it are diminishing and being lost. I don’t want to say that these traditions are becoming mere shells of their former substance, but when I try to talk about contemporary Japanese culture I become hesitant for some reason.When I look back to the time when I was a trainee in the musical company and I was beginning to learn classic ballet, jazz dance, tap dance and hip hop, etc., I felt uncomfortable being there in class working in which of the mirror wall. I believe strong sense of doubt was growing about the gap between the receptacle that was my body and what I was trying to express.At that time when I was feeling that I wanted to take a new look at the Japanese body and physicality, the motif I found was the Japanese sword with its significance as a symbol of the Japanese spirit in olden times. Today, the sword is not something we have as part of our lives, but I thought that exploring physical expression with the sword as my motif could provide even someone like me living in the present day with keys to the Japanese spirit and the physical sensitivities we have inherited, and what there is to gain as a Japanese dancer and what there is to recover from the past.And for dancers who train and refine our art to stand on the stage, there are things we share with the sword. Despite its beauty, it is a weapon, it can take lives but it can also protect them. That is the kind of dance I would like to do. I thought that I wanted to create a work that would create a basis for my dance expression by exploring the shape and form of the sword with my body through dance that I poured my soul into, pounding it out and polishing it to perfection.- The following year, 2007, you were officially invited by the Venice Biennale to perform your solo dance piece The Velvet Suite with a violinist. The artistic director was Ismael Ivo and the event theme was “Body and Eros.” The opening performers were all Japanese (Kaiji Moriyama, Ikuyo Kuroda and Fuyuki Yamakawa) and of the performances, yours was sold out. I was there to see the performances, but the event organization was lacking, but even though the performance started late, there was a big round of applause for you when it ended.

The encounter with Inbal Pinto

- That same year you performed with Shintaro Oue in an international co-production titled Hydra between Israel’s representative dance artists Inbal Pinto & Avshalom Pollak and the Sainokuni Saitama Arts Theater. It was just after Inbal made her international break with the work Oyster when she was still in her 30s.

-

I first met Inbal and Avshalom at the Theater Drama City production of

Sogen no Kaze

(co-choreography: Motoko Hirayama; direction: Koichi Ogita, 2003). Inspired by the Mongolian folktale

Suho’s White Horse

, it was a project that gathered internationally active young ballet dancers, and I also performed in it as a dancer. The Japanese creation scene often tends to be fiercely competitive, even cutthroat in atmosphere, but Inbal is always smiling and getting people to enjoy the creative process. She has us work freely, and the work proceeds almost as if we are writing graffiti. It is really wonderful to see her at work. Recently, I am increasingly doing collaborations with numerous performers, and I find myself constantly thinking of Inbal’s smile as something to emulate as I work. What’s more, she was pregnant at the time and her stomach was out quite a bit, but she was still dancing and choreographing. The people around her were nervous watching her, but she showed no concern. While she was moving around freely and playfully, her partner Avshalom was working on the theater portions, and the way they worked in a tag-team style was the greatest. It was very new and inspiring for me. It seems that she liked my movement, and it made me feel that I had found a kindred soul.After that came Hydra , for which I was fortunate to have Oue-san’s support as co-performer, and he came to Tel Aviv for a month to participate in the creation of the piece. The inspiration for that piece was Kenji Miyazawa’s Ginga Tetsudo no Yoru (Night on the Galactic Railroad), and I enjoyed seeing the ideas Inbal generated.I say creation, but it actually involved things like her standing up a metal pipe like a pole and saying, “Can you play with this?” or, “We are going to use black costumes, so let’s experiment with trying to make Japanese ninin-baori usually two-person overcoat “puppet grip” style jacket for 12!” And it wasn’t just Inbal and Avshalom, because Oue-san and myself are also the types who like to propose things we want to try one after another. So in the evenings when we returned to our lodging we would have a meeting to plan the things we wanted to propose in the next day’s session. We thought it might be good to use taketombo (a Japanese child’s toy made of bamboo cut in the shape of a helicopter rotor with a stick through the center for the child to spin between the palms so the rotor is sent flying up into the sky), but since there is no bamboo in Israel, we wondered what we could do. We thought we could find a video clip of kids flying taketombo on the internet and have it projected on a stage screen, but we decided, “No way!” Neither Oue-san of myself are that kind of person (laughs). So, we decided to use materials we had at hand to make something that would show the appeal of flying them. Finally, agreed we could try making a taketombo of paper, but when we flew it for everyone to see, they weren’t very impressed. So, after that we said, “Shall we try making a new kind of taketombo to take in tomorrow?” Those were the kinds of ways we spent our days in the creative stage.

- That sounds like an example of the kind of positive proposals that dancers can make.

- When I’m in my dancer mode, I’ll never be the kind that just does whatever the choreographer says. I believe that it won’t succeed as dance unless the dancer is involved to the point where they are eager to make choreographic suggestions of their own. I feel it is meaningless if the dancer does nothing more than the initial choreographed moves they are given. I believe the reason for the dancer’s existence is to change the choreography to a degree that it looks almost like a betrayal.

Because I am also a choreographer, I understand that there is a limit to the images a choreographer can put forth. There are some things that just come to mind and if you think it is good you tend to get obsessed with it. We are always battling to see how much the dancers can build on and develop those images of the choreographer and how much they will break those images down. Inbal was a person that I could carry on that kind of positive battle with.The Asian-type Body

- In 2013 and 2014, you were deployed to Indonesia, Vietnam and Singapore as a Cultural Ambassador of Japan’s Bureau of cultural Affairs. What was that experience like?

- Living in Indonesia on the island of Bali, I was really envious to see how the people had dance and performing arts as a part of their daily lives. There was a religious aspect to it, but there was also a reason to dance itself. This is something that surely existed in Japan in the past as well, but if asked if there still exists that kind of dance in Japanese life and in the regions of the country today, I would have to say, No. So, what is the reason for Japanese dancers to dance? That time in Bali became a time for me to think about meaning there is in making dance works to perform in theaters, in terms of one’s life.In Bali, the trees and bushes live their lives unhurriedly at their own pace, And you can feel that there is energy being born everywhere. It is completely ordinary for the people to say things like, “An evil spirit passed through here yesterday, didn’t it.” Behind the people’s house live many big lizards, and they cry in terribly noisy voices. Lizards hang from the rafters, cannibalizing among themselves, but they never fall down from up there. Perhaps because it is close to the Equator, the Moon appears very close and I couldn’t help but feel a direct contact with it. In contrast, the Moon in Japan seems to be off at an angle. Seeing how a change of angle can make a difference in your feeling about the Moon, I felt that my ideas about the world and about the meaning of dance had changed as well.

- How did your ideas about them change?

- It would be fruitless to try to bring the kind of relationship the Indonesians have with their dance to Japan as it is. Because it becomes a question of how much of the marvelous world it creates could be communicated in the Japanese theater space. But I believe it would be a rewarding challenge to attempt to succeed in. Just as watching Mademoiselle Mozart became a time to reflect on myself, I came to feel that I wanted to create spaces where I could share with others, including and audience, the things that I feel through dance.

- Do your productions Circus and Alice represent one of the forms you have found to achieve that?

- Yes, it does. And, since Japan also has dance forms that are brought to life in natural environments, like Takigi Noh performed on torch fire-lit outdoor stages, I would like to see this type of dance receive more attention and be appreciated more. One of the most important things that dance can do may be to help make sure that people don’t lose consciousness of dance performed as a form of worship to the earth that nurtures us, and dance in which it is the feeling of wind on our body that inspires it to dance.

- For the Japonismes 2018: les âmes en resonance (souls in resonance) program that takes place in Paris this year, you will be doing a collaboration with the Gagaku Ensemble Reigakusha.

- Gagaku is a kind of music that disappears as suddenly as it appears. With just a bit of pressure, it comes to the forefront with rich color, and when it recedes, it becomes as if transparent and disappears. It is my hope to do a kind of dance in which the body appears and disappears in this same way, a dance in which I seem to be present and yet a non-presence at the same time.

- You are a dancer of many faces, so we would like to ask you what kind of dance do you want to pursue.

- I refer to myself not as a “dancer” but as a “person who dances,” and now I want to reconfirm that conviction. And I believe that I also have to be a person who creates dance works as a professional. I want to place value on large scale work that is not confined to the theater, but at the same time I want to work to bring richer potential to theater spaces as well.

- In January of next year, you will make your debut as a director of opera with a production of Don Giovanni . We look forward to your activities not only as a dancer but as a director as well. Thank you for giving us your time today for a very interesting interview.

(*) Among the theater productions Kaiji Moriyama has performed in are director Akira Shirai’s

Lost Memory Theatre

(2014),

Yume no Geki–Dream Play (2016),

conceived and written by Marie Bassard/Robert Lepage, and

Polygraph (2012, 2014)

directed by Mitsuru Fukikoshi.

KAAT Kids Program

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

(2017, 2018)

Produced by KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre

Photo: Maiko Miyagawa

Circus

(2015, 2018)

Produced by New National Theatre, Tokyo

Photo: Takashi Shikama

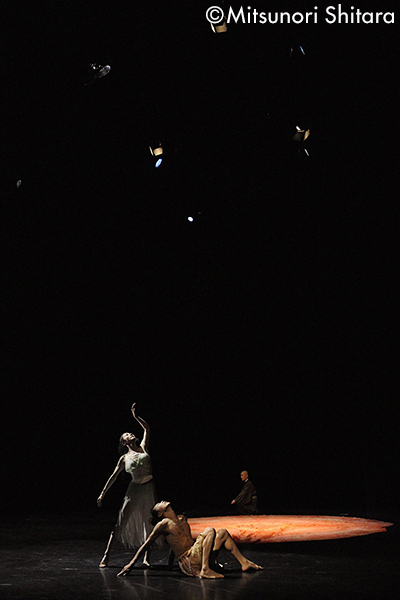

YOROBOSHI

(2003, 2009)

Produced by New National Theatre, Tokyo

Photo: Mitsunori Shitara

OKINA

(2004, 2009)

Produced by New National Theatre, Tokyo

Photo: Mitsunori Shitara

ARCHITANZ 2014

HAGOROMO

(2014)

Produced by STUDIO ARCHITANZ

Photo: Hidemi Seto

Photo: Maiko Miyagawa

Photo: Yoshikazu Inoue

KATANA

(2006, 2016)

Produced by Kaiji Moriyama ProjectRelated Tags