The original encounter with theater

- You were born in Kanagawa Prefecture in Japan in 1975. May we begin by asking how you spent your childhood years?

- My parents were teachers and our home was one where I wasn’t usually allowed to watch television when I was a child. The only programs I was allowed to watch were the animal documentary program Yasei no Ohkoku (Wild Kingdom) and a few TV anime shows that were considered safe for children, like “Sazae-san” and “Spoon Oba-san” and “The Wonderful Adventures of Nils.” So when I was in elementary school, I was the only one who couldn’t watch the many comedy programs like “ 8:00 Dayo! Zenin Shugo ” and “ Oretachi Hyokinzoku ,” and that set me completely apart from all the other kids.

- After graduating from high school, you entered the Film Arts Dept. of the Faculty of Arts of Tokyo Polytechnic University. Having been a child who wasn’t allowed to watch arts and entertainment, what made you interested in film?

- Because films were one of the few things I was allowed to watch when I was young. So I began going to the movies frequently and fell more and more in love with film. But, I had convinced myself that only eccentric people became film directors, so I was purely a viewer of films. But during spring vacation before entering high school I started going to a new cram school and there I happened to see a list of university entrance exams ranked by grade average and on it I found the category of “Arts-related.” That was when I first realized that you could study film at university and, though I thought there was no chance of me becoming a film director, I started to think that I wanted to work in some capacity related to film. Seeing that the number of required courses necessary to apply for a film course were few, I felt lucky, so I spent my three years of high school studying only the courses necessary to get into an art university, but I failed to pass the entrance exams for any of the universities I wanted to go to (laughs).

- How could that be (laughs)?

- It was because I was just a kid who didn’t really know anything. On the exams there were even questions about making film cuts. I had never done that and I didn’t even know what it meant (laughs). It was only after that that I found out you had to go to an arts-specific cram school in order to get into an art university. Still, in high school I was always watching movies, and the friends that I had at school were now gone, so life was getting darker and darker for me at that time. I though it wouldn’t be good for me to spend a year going to prep school [to get into an art school] alone like this, so I quickly took the second round of applications for the newly established Tokyo Polytechnic University and was accepted.

- Is there anything that impressed you from the movies you saw in those days that you feel connects to what you are doing today?

- When I am asked that, I always answer John Landis, who directed Blues Brothers , and I think that impression on me was great. But at university, when I’d say that, they really made fun of me. In my generation, directors like Jim Jarmusch ( Stranger Than Paradise ) and Patrice Leconte ( The Hairdresser’s Husband ) were considered artistic [in film circles].

- When you were in university in the 1990s, it was the peak of the popularity of independent art films and mini-theaters, wasn’t it?

- Yes it was. In the midst of that, when I would say that I liked movies starring Eddie Murphy and comedies Steve Martin, my fellow students would just laugh at me. You know, they would get drunk and start talking about Godard. I remember once, I just couldn’t follow what they were talking about, so I just said, “I’m leaving,” and walked two hours to get home. That was a time before smartphones and I got lost and had to find my way home by just following the railroad tracks, like in Stand By Me . I felt out of place, because I couldn’t follow the righteous path and I felt too embarrassed to go the sub-culture way.

- So how did this young film lover who couldn’t share the same wavelength with the people around him come to discover theater?

- I think it is still true today, but at the time the actors of the small-theater movement would act for free in independent films. It was in a case like that that I got to know people from the small-theater scene who acted in our independent films, and with that I started going to see plays. Then, thinking that it would be useful for when I directed a film, I started working as a director’s assistant for the theater company iOJO!

- From around the time you quit iOJO! You began participating in Dr. Ecuador’s Gokiburi Kombinat (Cockroach Complex) productions as an actor. Gokiburi Kombinat (Gokicon for short) is known as a “3K” (the term used for industries like foundry that are dangerous ( kiken ), dirty ( kitanai ) and hard ( kitsui )) company that puts on wild, extreme performances, sometimes containing violence and sometimes obscene action. Why did you decide to take part in Gokicon productions? Were you no longer interested in making movies?

- For four years in university I was making movies, but I didn’t have the talent to win any prizes and I didn’t have any connections to get a job in the industry. Japan’s economic bubble had already burst, and rather than joining a company as a fulltime employee, there was a feeling at the time that getting paid by the hour could get you more money, so it was a time when I just felt that things would work out somehow. When someone I knew asked me if I would act in a Gokiburi Kombinat production, I did, and that got me really liking theater. I put everything I had in it physically, to the point that I thought I was at the risk of dying at anytime, doing thinks that could only be done in theater. I would feel bad having people buy a ticket to come see my poor acting, but when I was putting so much on the line physically [in Gokicon productions], I thought it was OK if people paid a little more than 2,000 yen to come see it. But of course, it didn’t get you much money, so the grade of the rooms I lived in kept going down, until finally I was living in a room with no toilet or bath and getting by working at part-time jobs while performing in the productions.

- What kinds of plays were you going to see at that time?

- I had a girlfriend who had done theater in high school, and because I wanted to get her to like me we often went to see plays. The company I liked was Neko no Hotel. I also liked Akio Miyazawa of Yuenchi Saisei Jigyodan and Juro Kara.

- When was it that you wanted to write your own works?

-

When I was performing with Gokicon, I was also invited to perform with other companies and I acted in small-theater productions too. And to make it easier for people to remember my name, since it was too embarrassing for me to give myself a stage name, I came to just use my real name and put a fake theater company name after it, like Mitsunori Fukuhara (Pichichi). But then, when “Pichichi” was unexpectedly invited to perform at the “Uta Festival” (2002, West End Studio), I rushed to get together some actors and wrote a piece, thinking that I would write just this once. As it turned out, one of the other theater companies at the festival was led by a woman that I liked was in too, and since I wanted to get closer to her, I later went with the Pichichi actor N to see one of the company’s performances. After the performance, we went backstage to the dressing room to say hello and the woman I liked was there, and she said to the actor N I went with that she would definitely go to see his next performance. But when I said that I would also be performing in a play in some month, she said, “Good luck,” to me. I wondered what “good luck” meant? Eventually, it meant that for her I wasn’t worth seeing as an actor. So what could I do to win the approval of the woman I liked? Since the piece I had written earlier had been popular, I thought that maybe I could make it as a writer and director. I didn’t have any money, so eventually it was another year before I was able to rent a theater and put on a performance. As it turned out, that woman didn’t come to the show (laughs).

Leading several groups, transcending the everyday, fed by imagination

- So, because of that person you liked, you became the writer and director Mitsunori Fukuhara, didn’t you? By the way, you don’t have your own theater company but are active with a number of companies and units as co-leader. There is the unit “Pichichi 5 (quintet)” that you write short skit-like pieces in an omnibus type composition primarily performed by male actors, and the company Bed & Makings (*1) that you co-lead with the actor Kouichiro Tomioka and there is the two-actress unit Nippon no Kasen where the performers operate the music and lighting themselves, so your activities are quite diverse in nature. Also, you write a number of pieces for outside groups like the work Tsunzagi Kouro, Sareru ga mama that you wrote for Tsukikage Bangaichi (the unit lead by actress Shoko Takada) that was a finalist for the Kishida Drama Award and others.

- Since I adopted the policy of never turning down an offer to write, the number of offers grew and grew until things got pretty rough (laughs). But, you might say that I feel that when people show interest in [my work] I always want to respond by giving it another shot. I don’t think I’m a very interesting person, but if people ask for a work from me, I decided that at least I wanted to respond with something. It is probably my nature to try to do my best if I have the excuse that someone said they wanted to do [a production]. I am not a member of the unit Tsukikage Bangaichi but I have now written three works for them at their request, and in 2016, I wrote and directed a work for Tokyo No.1 Oyako (the theater unit of Sato B Saku, and his son Ginpei) and that may continue as well. And since I am still using name of a company that has never actually performed, I can’t really explain what is happening (laughs).

- I can’t help but be curious and ask what that fictional company name was for.

- It actually does have real meaning for me (laughs). When I was a student, I was made to write a paper about what it would take to create a Penguin Village. Penguin Village is the fictional village in the Dr. Slump TV anime series where the main character Arale-chan and the others live. The course I was taking was concerned with the question of how one can establish an experience of virtual reality, which was becoming popular at that time. What I proposed in my paper was that creating a museum full of items like Arale-chan’s big wind-up screw would stimulate people’s imagination to think about Penguin Village’s existence. Take for example the stories we have today about the warlords of Japan’s Warring States period (15th and 16th centuries). Isn’t it true that the remains of the castles and swords and documents they left behind have fed the proliferation of images—some of which may not be historically factual—of them we have today. That kind of fiction is really more interesting, and it leads to the creation and commercialization of related goods and computer games that become a big driving force in today’s actual economy. I found it very interesting how some scraps of information could spark the imagination and move reality as a result, and that is why I thought it would be OK to create a fictional theater company name. Half of the things on the Pichichi 5 website are in fact just made up, and it says that we are doing puppet theater (laughs). And it even attracts some inquiries about our puppet theater! In fact, I would even like to try making up some lies in an interview like this, and pretend they are true (laughs).

- I never realized that profile of yours had such deep meaning (laughs). Well, now I would like to ask you about your works. I have been following your work since the Pichichi 5 production of your 2005 work Hateshinai Monogatari (NeverEnding Story). That play was an omnibus of four stories about luckless men who manage to transcend their boring realities with humorous imagination, and I was particularly overwhelmed by the energy of the fourth story about five penniless men working for a moving company who in the end ride home on the dragon Falkor from the movie NeverEnding Story . Many of your early works were of this type, weren’t they?

- In my early career I though the only thing I could write that would be worth showing others was autobiographical stories. It’s the same as when I was putting my body on the line acting in Gokicon productions, since I was writing about myself, I at least knew that everything I was writing was true, so I figured that the audience would at least be getting their ticket’s worth. But soon, people were writing the same things about my work, like “cynical portrayals of luckless, uninteresting people” or “compassionate views of losers.” But, this was no joke. I don’t have any love of uninteresting people losers, and in my heart I certainly don’t want to end up a loser myself. Lately, I’ve also gotten tired of never letting myself sat anything affirmative about myself, so I have gotten away from that stance a bit. Thinking of it now, belittling myself was really just a way to shirk off pressure and take the easier path. I also feel that the ways I use imagination have changed too.

- I feel that the theme of your early works—transcending the boring everyday with imagination—grew even deeper with your first play for the inaugural production of Bed & Makings, Hakaba, Joshikosei (*2) (Graveyard, High School Girls), a story set in a graveyard in which the members of a high school chorus try to bring back to life one of their former chorus members who committed suicide and became a ghost, and your theater adaptation of the actor Daisuke Kato’s novel based on his wartime experience in a theater group to entertain the troops, Minami no Shima ni Yuki ga Furu (Snow falls on a south sea island).

- For me, Hakaba, Joshikosei was a story about using our imagination to find a way of purifying our feelings about a person who has died, so that we can transcend and live on, and Minami no Shima ni Yuki ga Furu is about men in a battle area seeking to overcome the harsh conditions of war by pouring their passion in to the fiction that is theater. But I feel that with these works I have cleared a certain stage in my writing.

- In your plays, you often have actors playing more than one role (character).

- I go to theater to watch actors perform, and I like to see them show us many faces. And when an actor performs a given role for two hours with intensity, he or she can get into and develop the character with great depth. But, since what I want to show an audience is not primarily the actor’s own in-depth interpretation of a character, what I want to see from an actor—although this may sound strange—is acting that is somewhat shallower (laughs). It only needs to be deep enough to turn on the switch to the viewer’s imagination somewhere inside, so that then I can have each viewer develop things in their own imagination for me. And since, when you think about it, that is also a switch that in part leads to misunderstanding, I think it is perhaps not really related to the actor’s abilities in character development.

- I feel that with Misui no hanzai Oh (2012, King of failed crimes) and Abuku Shakuri no Brigand (2016, Bubble Sobbing Brigand) the common people that are the main characters of the worlds you create use imagination as their weapon to stand up to the realities that face them.

-

Until recently, I wrote stories about characters using imagination to achieve their goals of things like getting enough to eat or being popular with pretty girls, but I feel that now my theme has changed to something more like what they should be using imagination to fight against. And I feel that now I am writing in the gap between my desire to write some kind of fiction that can stand up to reality and the need to not sound like I’m preaching. I think this is probably a reflection of the growing confusion in contemporary society and the increasing serious with which we have to seek answers. Maybe I am thinking that I want to make fiction work on reality more.

Stimulus from YouTube, manga and computer games

- What do you mean by making it work on reality?

- It’s hard to explain, but for example things like the flash mob group Improv Everywhere that has won a reputation on YouTube, I believe what they are doing really works on reality. Their performance I like best is “High Five Escalator” that they did on escalators of the New York subways. On the stairway next to the escalators in rush hour four people stand at intervals up the stairway with placards. The first one at the bottom says “Rob wants,” the second one says, “To give you,” the third says, “A high five” then the next one says “Get ready” and then Rob is there next standing in front of the last placard that says, “Rob” ready to give anyone that wants a high five. When they see this, even people who feel exhausted or sleepy get the message smile as they get their high five from Rob as the escalator carries them by. It surely gives those people who take the high five a little bit of happiness for their day, and after that they are sure to tell someone about it at work. I want to see if I can’t create that kind of artistic expression in theater.

- Is it that you want to reach out to people who have no interest in theater and don’t go to theaters? In that sense, the recent performance of Daichi wo Tsukamu Ryoashi to Monogatari (Two feet that grip the earth and stories) by Nippon no Kasen was held outdoor in a field at Kasai Rinkai Park wasn’t it? Passersby would see it and stopped out of curiosity to see what was going on.

- I wish there were forms of expression that were easier to understand, but all I can do is stories. In the end, I came to realize that it is stories that I like. So, I’ll ask that other people do the rest (laughs).

- You have also done wonderful work adapting other authors’ works for the stage. In 2017, you took the highly popular manga Orebushi (My Ballade) of Seiki Tsuchiya and adapted it as a play for the stage that won a lot of attention. It is a tale of youth about the main character who comes to Tokyo from the countryside with the dream of becoming a singer of the traditional-style Japanese popular songs (known as enka) that sang of the hearts and feelings of the common people of Japan in the Showa Period (1926 – 1989), and in your adaptation that uses famous enka songs to punctuate the main character’s struggles brilliantly, in in a way that gave us a sense of your own personal theory of gritty, physical theater art. How did the plan for this production come about?

- To begin with, the offer was for a production that used a famous existing story, and the proposal to use Orebushi was my own. I had read the original manga with a passion in my middle and high school days. And since it was a story that I liked I had made up my mind to take it on without compromise and do the very best I could with it. In fact, in 2012 I had approached the author, Tsuchiya-san, and gotten official permission to do an adaptation of the story for the stage, and it was just a week or so after that he passed away. So, the plan got sidetracked as a result. But I worked to restart the plan and, after roughly five years, the production was finally realized. In the original manga there are scene where the main character sings and the words of the songs were written in very strong bold-type letters across the page. Since the manga story was played out with the words of the enka songs, I thought about how I should handle that in my stage version. The manga also makes use of a device that has the main character become so self-conscious when he tries to sing in front of people that he can’t sing well, so I decided to play on that and make scenes where his true, deepest feelings are always expressed through the lyrics of the songs.

- That device worked extremely well in your stage adaptation. Because he can’t sing well in front of others, the song lyrics that he entrusts his sentiments to take on twice the impact, and that is complemented by the shared feelings of his friends—each with their own personal stories of disappointment—in the town and the back-street quarter who try to help him sing, added another poignant dimension to the enka songs and the songs of the common people. What’s more, the small-theater actors who acted in your play were especially fond of that aspect of the lives of the common people that you brought to the play. By the way, in recent years there has been a rapid growth of theater products based on Japanese manga or computer games, such as the so-called “2.5-D musicals” based on manga stories. Are you interested in these kinds of contents?

-

I love manga, so there are stories from them I am interested in, but what impresses me even more right now is what is going on in computer games. The game “Grand Theft Auto” that is now one of the biggest-selling games in the world, is really amazing! It uses actual cityscapes recreated in the finest detail in 3D images to create a virtual-reality world that you can walk around in freely. They call them “open world games” and one that I really get into is the American Wild West game “Red Dead Redemption.” It contains elements of virtually all of the Western movies that have ever been made, so you can virtually act out your own Western movie. I am really impressed by that potential of these “open world games.” If you compare it something in the actual world it would probably be close to Disneyland, but because theater is a storytelling medium, it can’t compare in these aspects. I envy these open world games that make you feel that you’d like to be there for hours on end.

Juro Kara’s Himitsu no Hanazono

- In January, you are directing Juro Kara’s Himitsu no Hanazono (The Secret Garden)(*3). We have been told that Kara-san is one of the writers you like.

-

I am very much influenced by Kara-san, but it is in a very unusual sort of way. When I was working as an actor, I acted once in a play by the drama institute of Kokugakuin University. At that time some people from Kara-gumi (Juro Kara’s theater company) came to borrow some of the institute’s lighting equipment, and through that connection I went to see Kara-gumi’s production of

Eye of the Jaguar

for the first time. That was a period when I had been I was going to see a series of plays that were listed in one of the event magazine’s “Silent Theater” feature articles, so I had the impression that silent theater was the basic form of theater. For our generation there was a mood that delivering lines in a loud voice with a high level of emotional tension wasn’t cool, but I wondered about that. But, that first time I went to see a Kara play, it was first of all the performance tent atmosphere itself that excited me, and the wildly vulgar vibes were overwhelming for me. The rhythm of the actor’s lines as the spoke them was simply so cool to my ears. What I had liked was the rhythm of speech of the black stand-up comedians turned actors in American movies, the rhythm of James Brown in Blue Brothers , and Eddie Murphy, the rhythm of speech as the singer urged on the audience at an R&B live performance, the rhythm of the minister’s preaching at a gospel session at church. Ever since I was in middle school, it was that rhythmical beat that they poured out their words to that I loved. I had thought it was something that was done in music, but when I saw the Kara-gumi play, I realized that it could be done in theater too. So, it was a moment when I felt a connection between theater and the things I had liked for so long. And in my plays now, I want the words to be spoken with a rhythm like that, and I want to create a viable reason for it that feels right.

- Is that what made you interested in Kara and start to read his plays?

- Yes. Because I couldn’t really understand it after seeing just one play, and even after reading them I couldn’t understand it (laughs). For a long time I didn’t understand what I was seeing. I saw [the play] once, I read it, I saw it again, and eventually it took about ten years before I finally felt I understood to some degree; it really took a long time before I felt that I had come to like it. The Secret Garden is a play that I wanted to do for a long time, and it was still with some fear and trepidation that I finally initiated a project to do it. In Kara-san’ plays, everything is put in words, even unnecessary things, so they are scripts in which everything seems to have a point of focus, and although there are some parts that trouble me, but there is something fun about being able to do a play that I like.

- Unlike in Kara’s era when there were strangely charismatic actors, it is harder today to do plays that really draw the audience into the experience, so I wander how you feel about this.

- Although it may sound like something a bit off the subject, I believe that most plays [today] are outdone by professional wrestling. Today, professional wrestling of the type that DDT (Dramatic Dream Team) does is really amazing. They take advantage of the fact that pro wrestling does in fact have preset scenarios and scripts and they do pro wrestling that has amazingly interesting stories and physicality that no actor can match. For example, there is a pro wrestler named Kota Ibushi who wrestles with a Dutch wife named Yoshihiko! In other words it is a one-man play, but if he was just doing things like doing a back-drop on the Dutch wife then it was something that could be done by an actor, but he actually has the Dutch wife do a back-drop on him! (Laughs) Ibushi has a famous saying: “The stronger I get, Yoshihiko gets equally strong.” And there is certainly truth to that; because it’s like fighting with a part of yourself. It is all physical expression, and though it is as stupid as anything could be, it is so amazing it can bring tears to your eyes. The audience has no trouble at all accepting Yoshihiko as a wrestler, and when Yoshihiko successfully pulls off one of his moves, the crowd goes, “Wow!” and cheers for him. The whole audience, even people seeing it for the first time, all share in the same lie without any introduction, and when the match is over, they are all say they are in tears. What is this shared feeling of participation in what is in fact a deceit? It is powerfully moving.

- There is an element of the creative power of imagination that you have long been portraying there, isn’t there?

- When I think about how I can compete with DDT, I think it is with strength of storytelling and creating good scripts. And maybe that is the reason that lately, I feel that the lines I write for my characters are getting longer and I am enjoying the power of words more again. When I experience something bad, I can’t come to terms with the emotions until I put it in words or make it into a story. I can’t digest the emotions until I do that. So, I think that is why I will continue to put things into words.

- When I watch your plays, I indeed get the wonderful feeling of emotions inside you that you can’t put into words gradually finding expression in words.

- Like the way I watched a variety of different emotions being explained in films when I was watching so many in my adolescence, I probably want to go on having those kinds of realizations about emotions and the realities behind them. And since new emotions continue to arise as the times change and as I get older, and I as I think about how to express those emotions into words, I feel like there will never be an end to this process as long as I live. Well, I will probably get older in this way and maybe I will start doing Haiku poetry [like so many older people in Japan do] someday (laughs).

*1 Bed & Makings

Began activities as a company in 2012 with the work Hakaba, Joshikosei (Graveyard, High School Girls). This theater company of Mitsunori Fukuhara and Kouichiro Tomioka takes the theme of “philosophy even a monkey can understand” and the concept of making this contradiction-riddled world a little easier to live in. The company name is intended to mean making theater (bed) and it presents production staged in unusual spaces outdoors or in places like warehouses.*2 Hakaba, Joshikosei (Graveyard, High School Girls)

This is the popular play that premiered in 2012 as the inaugural production of theater company Bed & Makings and has since been re-staged for performances in new productions numerous times. Set in a graveyard, it tells the story of the members of a high school chorus who can’t understand why one of their former chorus members committed suicide and accounts their efforts to bring their friend, who has now become a ghost, back to life.*3 Himitsu no Hanazono (The Secret Garden)

This play was written by Juro Kara for the maiden performance of the Honda Theatre in 1982. It is set in one room of an old apartment in the Nippori district of Tokyo. The room’s occupant, a cabaret hostess named Ichiyo is involved in relationships with three men (her husband, the pimp Onuki, a customer at her cabaret who believes he was her lover in his previous life and keeps spending money on her, and the nephew of a leading member of the community who is out to win her love) in a story crisscrossed with reality and delusion.

Bed & Makings 3rd production

Minami no Shima ni Yuki ga Furu

(Jun. 12 – 22, 2014 at Special tent theatre in Shiokaze Park-Taiyo no Hiroba, Shinagawa, Tokyo)

Photo: Nobuhiko Hikiji

Orebushi

(May. 28 – Jun. 18, 2017 at Akasaka ACT Theater)

Photo: Tomohiro Akutsu

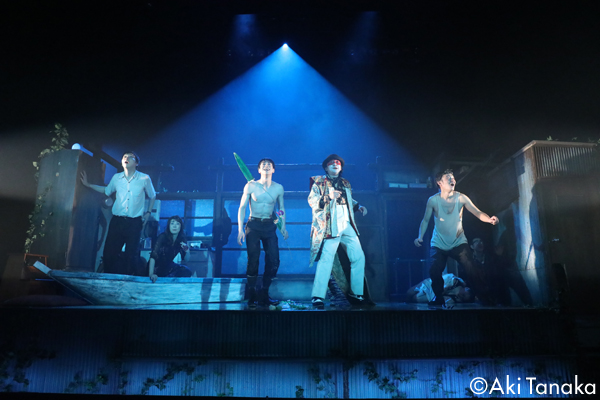

Himitsu no Hanazono

(Jan. 13 – Feb. 4, 2018 at Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre – Theatre East)

Photo: Aki Tanaka