- We have heard that you started doing theater in college, but prior to that were there any experiences that particularly got you interested in that direction?

- When you ask in that way, what comes to mind is seeing the movies Atami Satsujin Jiken and Kamata Koshinkyoku about the time I entered middle school. They were so interesting, but at the time I didn’t know of course that they were based on the original plays of Kohei Tsuka. In fact they must have been so fascinating to me that for our middle school culture festival I did a play based on Atami Satsujin Jiken .

- Was it with your school’s drama club?

- No. It was what we chose to do as our class project for the culture festival. Tsuka’s movie was actually a Kadokawa Pictures production, which were at the height of their popularity at the time (movies produced by Kadokawa Shoten publishing company as a project conceived by the company’s president at the time in the late 1970s, Haruki Kadokawa as a way to increase sales of the company’s books by turning them into movies staring popular young singers and actors) so most of my classmates had seen the movie, and when we did our class play based on it, it was quite a success. Looking back now, I think many of the Kadokawa movies of that period were actually very drama-based in nature. The characters talked a lot and the individual scenes were quite long. I feel that they also had a very experimental flavor. Anyway, we used the Kadokawa book based on the movie’s scenario to make it into a play. I didn’t know there was an original play (by Tsuka) that it was based on, so I just adapted the text as a play, and I directed it and also acted in the role of the main detective in the Atami murder mystery story.

- From the way you speak and the way you hold yourself now, it is hard to imagine you becoming very emotional [like an actor], so I find it surprising that you would have been so active [as to direct and star in a play] like that.

- Human beings always keep changing, don’t they? At the time I was actually the type that liked to stand out and be noticed, and do things like talking back to the teacher. It was also a time when manga series like Be-Bop High School and Shonan Bakusozoku (Shonan motorcycle gang) about rebellious or delinquent youths were popular. The original mangas would then be made into anime and then movies. That may have influenced my actions. Of course, I didn’t become a delinquent (laughs). When I talk about those times, my friends today say they can’t believe I did things like that.

- By the way, did your family have any influence in your getting involved in theater?

-

No. My parents had no interest in theater or movies. But I did have an aunt on my mother’s side who lived in the Ebisu district of Tokyo and used to take me to movies and things. Together we would go to the movie theaters in the Shibuya district and watch one movie after another, and sometimes they would be rather adult-oriented movies. The most recent project I have been working on is the script and directing of a musical based on a manga by the famous manga artist Osamu Tezuka titled

Ue o shita e no Diletta

(Ups and downs of Diletta *1), and this was also a manga that I first read at my aunt’s house. By the way, until about my middle school years I wanted to be a manga artist, and I often spent my time writing and drawing manga.

- You would have been in middle school in the 1990s. That was the golden era of manga magazines like Shonen Jump . So you were being exposed to this subculture in your most impressionable years, weren’t you?

- Yes, I was. By the time I was in middle school, there were stacks of copies of Katsuhiro Otomo’s manga Akira in every bookstore. Just from the outer appearance of the characters it was so cool, with something very impressively foreign about it. But it was such a long time before the sequels were published and before that I read other things that came out like Domu (A Child’s Dream).

- Are there any other experiences that led you toward theater?

- One of the thinks that directed my interest toward theater immediately was the seeing Issei Ogata’s one-man plays on television. It was a time when there was a boom in comedy and comedy pairs like Tunnels and Down Town and Ut-chan Nan-chan were very big on TV. And, on Fuji TV that had a late-night program that introduced sharply edgy artists like Issei-san. Issei’s works had a bit of darkness, a bit of “poison” in the lines of the script and in the way people were portrayed. That really attracted me, I feel. I was also drawn to the passionate drama in the way people were portrayed in Tsuka-san’s works, but that poisonous edge in the scripts and the black humor of Issei was something that really attracted me as extremely cool. When I was in high school I even went to see Issei-san’s live performances at the Shibuya Jean-Jean small theater. Of course, seeing a live performance was several times more impressive, more cool than watching him on TV. So, when I went to college I decided to join the drama club.

- What kinds of things did you do in that drama club?

-

I did acting with Issei-san as the actor I emulated, but the actual acting I had to do I found to be very constraining. In fact, I learned those stages I saw Issei-san performing were not his own product alone but thanks to the presence of the director Yuzo Morita. Then I realized that what I was really interested in doing was the work of a director like Morita-san, and from that time my interest shifted to playwriting and directing. At the time, the plays our college drama club was doing were play that our upperclassmen were writing influenced by the plays of Hideki Noda and Shoji Kokami, which were different in color from what I wanted to do. At the time I also liked Naoto Takenaka, so I went to see the Takenaka Naoto no Kai performance of Kowareteyuku Otoko (*2). That was my first and highly inspirational encounter with the works and directing of Ryo Iwamatsu (Born 1952. Playwright, director, actor and film director. Representative of the Piccolo Theater Company, Hyogo).

- That was a life-changing encounter, wasn’t it?

- Yes. At the start of the play the main character, Takenaka, begins to speak with his back turned to the audience. It was a collection of fragmented scenes that start out strange like that and go on to end strange, like a road movie of Jim Jarmusch. In the leaflet I got at that performance, I saw an announcement about an audition for young actors to act in play that Iwamatsu would be directing and I auditioned for it. I was in my third year of college and the work he directed me in as an actor was a 1994 performance of Ice Cream Man (Premiered 1992. Set in a retreat facility for people preparing to take their driver’s license test, it portrays the complicated human relations that develop between the trainees).

When Iwamatsu-san is in the rehearsal studio a variety of actors come to watch, and that experience immediately expanded my world of experience. For young people around the age of 20 [like I was] it is a very stimulating environment, and I became obsessed with the desire to be a part of their world. I wrote scripts and directed them copying Iwamatsu-san’s style for performances at a studio at my college, and Iwamatsu-san would come to see them. He would give me numerous high-level critical opinions that I didn’t understand at all at the time, but later I would realize what he had meant, and the realizations would strike me with the force of body blows. But, generally speaking, isn’t that the way things go with advice from our seniors (laughs).- In Japan, it is often the case that people will start writing plays and directing them and then form a theater company while they are still at university. The case will be different if they become part of an existing theater company, but I believe there are few cases where a young playwright will meet a mentor like Iwamatsu-san.

- I believe I have been very fortunate. I believe that Iwamatsu-san saw some degree of potential in m, and he told me to send him the scripts I wrote, and after he read them he would call me to a café and kindly give me advice about them directly. Thus I was able to have that kind of relationship with a mature mentor while still in college and get my self-conscious ideas shot to pieces, come to my senses and realize that I was no one. I truly believe it was a great thing to experience. And, since I was able to work with a mature mentor like that from the beginning, everything felt natural when I began doing productions professionally myself.

- What do you have in mind when you begin writing something?

- At first I was just copying Iwamatsu-san’s work. I was thinking about his perspectives, what you could call his way of finding interesting aspects of things … the things of interest that he would find in the everyday or in people’s relationships to build a play around.

When I begin writing, I often begin with an idea about a place. I get a picture like that of a basement room and a hatch to enter it that suddenly opens, or I might say, “a loft might be interesting as a place.” Then I think about where I would position people so there could be conversations between the loft and the ground floor. I can take that kind of visual starting point and then ask what kinds of people would be in such a strange place. I still have a tendency to think in that way. Like Iwamatsu’s setting a toilet without a door for a humorous touch, I will make settings where one place, or one thing is strange, and I those kinds of touches impulsively. When you open up a room’s fusuma (sliding panel that opens to the hall) suddenly outside there is a view of a wide expanse of sea, but the people in the room are not surprised by it at all and simply continue their conversation; that is the kind of situation I like.During one period, I was really writing mostly with holes or basements as these “places” I worked from (laughs). And for that reason, the things I wrote naturally had an aspect of theater of the absurd. It was something I was doing consciously, it was just that when I wrote about things I was attracted to, that naturally became the type of theatrical world it produced. I would think, “This is the kind of picture I want to begin from and to end with,” “I want to write about the things that would happen in that picture.” But, I never begin creating a work by thinking that I want to write about love or about death.At that time I was feeling satisfied that I was copying Iwamatsu-san’s style skillfully, but when we performed my play Drill on Ue no Kyodai (2003, literally “Brother and Sister on a Drill”) Iwamatsu-san pointed out to me that, “I think there is a gap between what you want to do and the way you are writing.” I couldn’t understand at the time what he was trying to say, but it caused me to start thinking anew about what I was doing, and that led me to change the way I wrote.- In 1996, you joined in the activities of the theater company Puriseta founded by the actors Masahiro Toda and Shoichiro Tanigawa, and in 2000 you started your own theater company Penguin Pull Pale Piles (PPPP) that you did the writing and directing for. Drill on Ue no Kyodai was your fifth production with PPPP.

- Yes. And then the first play I wrote after intentionally changing my writing style was One Man Show , which we performed that same year (PPPP’s sixth production).

- One Man Show is a story about a man who spends all day and night in his room filling out postcards to send in in hopes of winning sweepstakes and in the process creates fictional people to increase his number of applications, and as the play goes on a seemingly unrelated patchwork of episodes eventually begin to fit together like the parts of a jigsaw puzzle into one coherent story. People have said that there are inspirations from works like director Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction , David Lynch’s Lost Highway , or Paul Auster’s Ghosts . This play won the Kishida Drama Award, but can you tell us specifically in what ways you changed your writing style with it?

- Until then I had thought that the dialogue should have some degree of reality, and I wrote without questioning that assumption. That meant that there had to be quite a lot of repetition within the conversations to maintain the coherency, which in turn slowed the pace of the story’s progress. But when I threw that assumption out and started writing in a way that had one character give a long monologue or greatly abbreviating the contents of a dialogue, the dialogues began to progress much more smoothly. With this, I found that I could paint the pictures I wanted more fully and progress to the points I wanted to arrive at.

- What were the “pictures that you wanted to paint”?

- What indeed … the world of One Man Show is a strange one, with frequent jumps and gaps in the timeframe. I think that I wanted to try and see if I could get the audience to enjoy such complex worldview and such a complex theatrical structure. I had been struggling for a long time with the question of whether it would be possible, and with this play I finally felt that I was getting close to an answer.

- There are some playwrights who write notes to the actors in the stage script, but what is your relationship with the actor like? You have worked with actors including Masahiro Toda of Puriseta and Shoichiro Tanigawa who was with Tokyo Kandenchi (a company founded by Akira Emoto, Bengal and Toshiki Ayata in 1976. Representative: Emoto) that Iwamatsu was also with for many years. You were just 24 at the time. [Naoto] Takenaka was also an established actor with a strongly individualistic style, and in 2013 you launched the Naoto and Kuramochi no Kai.

- Well, with Puriseta I think I always began by thinking about what kind of roles I would like to see Toda-san and Tanigawa-san acting in. It is the same when I was writing and directing for Takenama Kikaku which was formed by Takenaka and the actor Katsuhisa Namase. I am thinking about what kind of relationship it would be interesting to see the two of them in and what kind of scene it would be interesting to place them in. With PPPP, the sense I have isn’t of starting from the actors but more of what I want to do with the play’s development.

- From around the time you presented One Man Show you have not only been working in the “small theater” context but have been doing more work in large-scale theater and taking on more writing and directing commissions for outside productions.

- When it is not a case of what I want to do but one where I am commissioned to do a specific work or subject, it is an easier task. When I am told that I can do anything that I want, the number of choices of what direction to proceed in just grow to the point where it is so hard to take the first step, but when I have been given a set of conditions to some degree it is easier to narrow down the direction I want to proceed rather quickly. If there is some clear goal that you are aiming toward, it is easier to focus on specific aims.

- When you do this kind of work, the focus turns to the original work. There are many works that attract attention, domestic an foreign novels, manga, traditional plays [Noh, Kabuki] and classics, contemporary. The first time you worked from an existing original, now more than ten years ago, was Bat Otoko (Bat Man, 2004) based on a short story by Otaro Maijo, a charismatic masked writer know for his stories about controversial subjects written in a fast-paced style. It is a mystery inspired by the murder of a weak, scruffy-haired, dirty homeless man known as “Bat Man” because he always walked around carrying a metal baseball bat, who ends up getting murdered in a counterattack. How did you approach this story?

- At first, it troubled me, or you might say frightened me. I believe that feeling came from my fear of disappointing the fans of Maijo’s original. But the more thoroughly I read the original, I realized that the only way to approach it was with an attitude of, “This is how I interpret it,” and then just prepare myself for the worse [criticism of my interpretation]. Once I adopted that attitude, I was able to get into the writing of the script.

- After that, you wrote the script Neji to Shihei (2009, literally Screw(s) and Bank Note(s)) based on the Kabuki play Onnagoroshi Abura no Jigoku (The Oil-Hell Murder), then you wrote Hanago ni tsuite (2014, literally About Hanako), a play that bundled together parts of the Noh play Aoi no Ue (Lady Aoi), the Kyogen play Hanago and the Modern Noh Play Hanjo for a production of the Setagaya Public Theatre’s contemporary Nohgaku series, and then your latest work Osei Tojo based on eight short stories by Edogawa Ranpo (Premiered at Theater Tram, Feb. 2017. Starring Hana Kuroki, Hairi Katagiri and others). These represent a truly wide range of original works you had taken on.

- It is not that I am especially well versed in the Japanese traditional classics or modern Japanese literature. I would say that the only writer from modern Japanese literature that I could profess to admiring is probably the work of Natsume Soseki. With adaptations from existing original works, it is a matter of what you find interesting in them, and with the Noh and Kabuki classics and Edogawa Ranpo (Rampo), I would say that what I found interesting in them was a bit different from usual. The stories in the classic Noh and Kabuki play (recitations) are simple and thick and they have a lot of spaces left empty, which makes them interesting to work with, and that makes it fun. No matter how much you may branch off in so direction, the original story has the strength to always bring things back to center, so you can really play around with them.

On the other hand, with Edogawa Ranpo, I get the impression that the stories themselves are very severe, and I felt that I was enjoying his humor. When I was a student I like Ranpo and read a lot of his works, and while among the general readership his work is considered “ero-guro” (erotic and grotesque) stories, I find a special humor in them. He adds a lot of ornamentation to seemingly trivial things in a concerted effort to make them grotesque, but sometimes he goes too far. That is something that I really felt an affinity for. Personally, I continue to write scripts at a pretty fast clip, and at time I will really have only one idea that I want to use, and so I often just push through with single approach, so I think I understand something about how Ranpo felt when he wrote (laughs). I think there is a minimum limit to the number of ideas you need to make a play last for two hours. And if you try to write without having found that minimum number of ideas to work from, it gets naturally gets difficult to keep writing. Because you are trying hard to make it look as if you have something that isn’t really there and you have to work hard to make it last. That is the area where I feel Ranpo’s humor. With Osei Tojo that is what I wanted to enjoy working with.- Osei Tojo is a story about a husband named Kakutaro who has pulmonary tuberculosis and not long to live, and is putting up with the infidelity of his wife Osei, who finally kills him by shutting him up in confinement for a long period. The storyline consists of a number of stories played out in parallel, such as episodes of the young days of Osei, who has now turned villain, and an episode about a man who has fallen in love with a girl in an illustration and enters the picture to be with her. What kind of ideas did you have in making this into a play?

- It is a work that compiles parts of eight short stories into one, and one of those stories is Osei Tojo , which word-for-word is a cool title, so I used it for the title of my play. I had the idea of making Osei the rival of the detective Kogoro Akechi, the fictional private detective in Ranpo’s famous Detective Kogoro Akechi series and I even used Osei Tojo as the title of the work, but in the end, that idea didn’t take shape in the finished play. I found the character Osei very appealing as a woman with a different ethical perspective from others who is able to enjoy things evil, and I was fascinated with that reverse setting and was determined that I would use that device, even if Ranpo hadn’t been able to. So, I searched for a number of short stories in which the characters could be interchangeable and constructed a storyline in which Osei served as the character to connect the stories. However, simply interchanging Osei with characters in the other stories wouldn’t be enough to create an overall continuity. So, I had to ask myself what kind of character image could be created that achieve a sense of continuity. That is when I got the idea to use scenes with Osei as a young girl, and the character that I created for the young Osei would then change the reactions to her of the other characters, and with that it became a lot of fun to see how the plot developed as a result. As the profile of that Osei character grew more and more complex and weighty in my mind, I experienced the birth of a very strong character.

- The set for your play this time was a two-story structure. In the center of the 2nd floor was revolving wooden horse that symbolized Osei’s youth and also Ranpo’s labyrinth world, while the 1st floor had three rooms, each built on a movable stage floor that moved forwards and backward. This set, with its capacity for quick changes, functioned beautifully to show the progress of the play’s parallel plots.

- Since I have done a number of plays with scenes that change at a quick tempo in line with multiple parallel stories progressing simultaneously, this has become a sort of genre in itself for me. In the past I have used revolving stages (circular plates), but since I wanted to try a different device with Osei Tojo , I consulted with the set designers from the early planning stage. What they came back with was a sliding frame type plan that divided the set into parts that could be moved separately to the front or rear. This gave birth to a structure by which characters and things could suddenly come forward out of the darkness and then disappear back into the darkness again, which fit beautifully into Ranpo’s unique world. But, since the actors were playing several roles each, it made things difficult because the actors had to move around on a moving set (laughs).

- One of your works I recall that used a circular revolving stage plate was Shinpanin wa Konakatta (2008, literally The Referee Didn’t Come), As with Osei Tojo , it was staged at the same small-theater space Theatre Tram. The setting is the newly independent fictional country of Pariero, where amid much confusion everyone is trying to develop a new sport to become the national sport. And here again you had seven actors playing multiple roles of a total of 22 different characters.

- That was the first play I used a revolving stage plate with. I have a strong desire to increase the number of options I have as a director. So, in my discussions with the stage art staff, when they make a number of suggestions, I will usually choose the ones that I haven’t used before. With Shinpanin wa Konakatta , it all started when I said selfishly that I wanted to use a revolving stage plate because I have never used one before, and I wrote the script based on that device (laughs).I showed a game of this fictional sport being played on the revolving stage, but since it was my first time using one, there were places where I didn’t make good use of the device.

One producer who saw this play asked me to write another one with the same kind of direction, and the result was a second play using a revolving stage in 2011, Kamatsuka-shi, Horinageru (literally Mr. Kamatsuka Gets Tossed, a comedy about a man named Akashi Kamatsuka who seeks to be a “perfect butler” but ends up being caught up in various kinds of trouble each time, but with tactfulness and using all his resources, he gets manages to through each pinch. It went on to become a series.). And this time I was able to use the revolving stage skillfully. Kamatsuka-shi was the first play I did that was clearly stated from the beginning to be a comedy, and it was the first time that I experiencing the pressure of having said that I was going to make people laugh and the satisfaction when they did. It was after this play that more people began to come to me and say they wanted to work with me on productions.- Another case where you were working from an existing original story was with the script you wrote for the 2014 production based on Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel Never Let Me Go (Japanese title: Watashi wo Hanasanaide ) directed by Yukio Ninagawa (link to drama database). This was the world-famous novel written in the person telling the story of a female clone raise to provide organs far transplants. It became a revolutionary stage in which the national setting and race of the characters was changed without destroying the world created by the original novel at all.

- It is a novel that I love, so when I got the offer, I didn’t hesitate at all about accepting it. And Ishiguro-san kindly told me that it would be fine for me to change the country and adapt it as a play. Having been told that, I decided to set it in Japan. Since the subject is a facility where clones were being raised as organ transplant donors, I thought that any of the developed nations would be a viable setting. Also, although is a story told completely in the first person by the character Kathy, I decided to change that. Since the story is told completely from the perspective of Kathy, another character in the story, the girl Ruth, is depicted as a bad-natured person, but I decided to see what would happen if I added another third-person perspective. Perhaps there was some good reason that Kathy deserved being picked on unkindly by Ruth. By removing the storyteller role, I was free to write the script while imagining conversations that might compensate for the one-sided perspective.

- Are there any rules that you set for yourself when adapting an existing work for a stage script?

- One is to never change the plot. This is partly out of respect for the original work’s author and fans, but it is also based on my belief that the significance of working from an existing story is lost if you are going to change the plot. Said in another way, putting together a plot is a very difficult and painstaking task, and since there is already a wonderful plot in the original work, there is no way I am going to go through that painful effort to change it (laughs). There are some people who try to change the plot of the original work, but I can’t help but thinking that is a waste. If you keep the plot in tact, the process of writing a script and directing it is really enjoyable. Since you always have that strong place (the original plot) to return to, you can venture as far afield from it as you wish and still return safely.

- In May of this year (2017) you are presenting Ue o shita e no Diletta (Ups and downs of Diletta) an adaptation of Osamu Tezuka’s manga. In the case of a manga, which is work with pictures, are there any rules you follow?

- When the original work is a manga, I also keep faithfully to the rule of maintaining the integrity of the plot. However, because I respect the original, I believe it is wrong to try to create three-dimensional representations of the illustrations; I believe it is wrong to tamper with the pictures. Trying to work with the illustrations can never produce a product that is better than the original. So instead, I think about what the artist was trying to express with the illustrations, and if I take that as the approach, there is no way you will be violating the original art.

For example, in the case of Jiletta , the experimental nationwide public broadcasts of the fantasy world being directed by one of the main characters, Otohiko Yamabe, turn out to be so erotic in nature that they cause a reaction in which many citizens object to the broadcasts. In the manga this is represented by very erotic pictures, but rather than sticking to the erotic images, I decided that as my interpretation I would think about ways to communicate instead the developments of the public reaction of opposition to what he was doing with the broadcasts.- Also, in August you will be presenting Kamatsuka-shi, Hara ni Osameru , the fourth in the series of comedies about the aspiring “perfect butler” Akashi Kamatsuka and the various troubles and mysteries he must overcome. In your works, humor has become an important element.

- Yes. No matter what kind of work I am creating, I want there to be some point in it where I am free to play around and do something foolish or absurd. Rather than being something I do deliberately, I would say that it is something I do intuitively; it is as if I always come to a point in a script where I feel that if I don’t insert a bit of something funny or absurd, the play won’t be able to move forward. At some point, both for my sake as the writer and for the audience’s sake as the viewers, I want everyone to realize and accept for a moment that “this is something I am making up, this is fiction” and then reset our perspective based on that realization. I get a very strong sense that if there isn’t such a moment the play can’t progress. So, in that sense it may be a bit different from just a love of comedy and laughter. What I like is that kind of laughter that results when the tension of the drama is broken by some line that makes people say, “Why would you say something stupid like that at a [dramatic] moment like this!” That is perhaps why it is called nonsense or the absurd.

- You want to make sure that you share with the audience the prerequisite assumption that a play is fiction. And that is the reason for the laughter and the humor.

- Yes, because, I don’t want to transplant realities to the stage just as they are. If you don’t transplant things with the affirmation that “this is an imitation” there is nothing interesting about theater. When you include a nonsensical or absurd scene that shows our conviction that what we are doing here on stage is fiction, it also helps the actors to give expression to their acting with conviction. And it enables everyone to be able to make theater without the kind of misguided tension that makes us think that there are things we must avoid doing because of the supposed emotional flow of a given scene. If we are fully aware that what we are doing is not reality [but fiction] from the start, instead of feeling that from A we have to move to B [and the C and so on], we have the freedom to try jumping ahead to something else. If you can do that, then both the actors and the audience feel that theater is really fun, and something to enjoy.

- More than twenty years have passed since the time you were learning from Iwamatsu-san about how to find interest in people and the world. Do you feel that that guiding principle has changed in your thinking today?

- I am always conscious that when an incident happens, I don’t want to approach it from the start with an attitude of “who is wrong here?” and “which side should I depict it from?” When something happens, my interest is in what actions people take, the person who did something wrong, the people that criticize the person and the people that defend the person. So, while it is people I am depicting, I want to take bit of a bird’s eye view of the bigger picture, or you could say that it is the society at large that these people are crawling around in and I think what I am interested in is looking at the society. That perspective has remained the same all this time. On the other hand, the society and the people are always changing this way and that, and that is also something I am interested in, so I’m pretty sure I will never get bored.

*1 Ue o shita e no Diletta

Manga Sunday magazine in 1968. Set in the mass media world, it is a little known masterpiece painting a satirical picture of growing human ambitions and greed and the “civilized” society that gets swept along with it.*2 Kowareteyuku Otoko

Debuted 1993. A work depicting the deepening love-hate relationships of a group ad agency employees who have gone to live together in an apartment in a seaside town where they are managing the windsurfing event their company has planned. This work and Hato wo Kau Shimai won Ryo Iwamatsu the individual playwright award of the Kinokuniya Drama Awards.

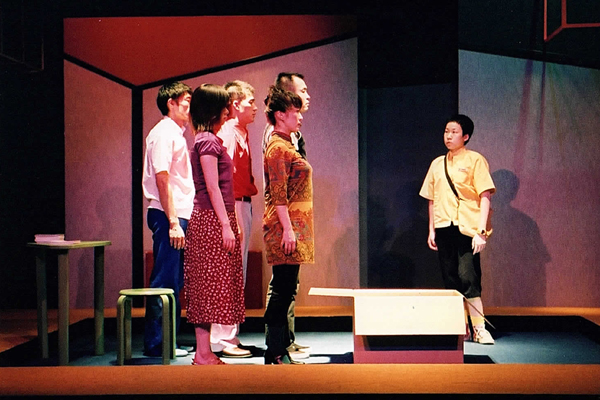

Penguin Pull Pale Piles

One Man Show

(Aug. 2003 at Theatre Tram)

M&OPlays Naoto to Kuramochi no Kai

Jiba

(Dec. 2016 at Honda Theatre)

Photo: Kazuhiko Shibata

Setagaya Public Theater production

Osei Tojo

(Feb. 2017 at Theatre Tram)

Photo: Shunki Ogawa

Penguin Pull Pale Piles

Shinpanin wa Konakatta

(Jul. 2008 at Theatre Tram)

Photo: Nobuhiko Hikiji

Saitama Arts Foundation, HoriPro

Never Let Me Go

(Apr. – May. 2014 at Sainokuni Saitama Arts Theater, Main Theater)

Photo: Takahiro Watabe

M&OPlays Kamatsuka-shi, Horinageru

(May. 2011 at Honda Theatre)

Photo: Nobuhiko HikijiRelated Tags

Yutaka Kuramochi

The vision of Yutaka Kuramochi

A fascination with people and the world

Yutaka Kuramochi

The playwright was born in 1972 in Kanagawa Prefecture. Graduated from the Economics Department of Gakushuin University. Began acting, playwriting and directing as a member of the college drama club in 1992. In 1994 he appeared as an actor in the production of Ice Cream Man directed by playwright, director and actor Ryo Iwamatsu for young actors. After that, Kuramochi was mentored by Iwamatsu as a playwright and director. In 1996, Kuramochi joined in the founding of the theater company Puriseta with actors Masahiro Toda and Shoichiro Tanigawa. Until quitting the company in 2004, Kuramochi served as the playwright and director. In 2000 Kuramochi started his own theater company Penguin Pull Pale Piles (PPPP), after which he did the writing and directing for all of the company’s productions. Writing with a uniquely cynical viewpoint and the ability to weave rewardingly subtle dialogue, his plays skillfully create an atmosphere similar to theater of the absurd with sudden appearances of the other worlds that exist back-to-back with everyday life. As a director, Kuramochi is recognized for his productions’ imaginative stage art that helps create bold and tricky theatrical worlds within clearly restricted spaces. Kuramochi also applies his skills to adaptations and stage scripts based on existing works ranging from novels to Noh and Kabuki plays. Recently, he has also expanded his activities to scriptwriting for TV dramas and comedy routines. In 2004, his play One Man Show won the 48th Kishida Drama Award.

Interviewer: Kumiko Ohori