- You were born in Yokohama in 1977 and you continue to live in Yokohama. Would you begin by telling us something about your childhood? Did you think that you wanted to be a writer from the time you were young?

- At the time of my first memories from childhood, my family was living in an apartment building that had a bookstore on the ground floor, and I remember always peeking inside it every day as I passed on my way to nursery school and back. In fact, our apartment was always full to overflowing with books. My father was a designer of things like bridges and ships, and there were always piles of books about such things, as well as many books about art that my mother loved, foreign novels and many spy and detective novels like Ed McBain’s “87th Precinct” series. Although I was too young to understand a lot of the contents, I spent a lot of time reading those kinds of books. I though the vinyl-covered Hayakawa Bunko series books looked cool and had a special feel to them that I liked.

- Did being a book lover naturally lead to interest in writing as well?

- It wasn’t as if I liked writing all kinds of things, and I hated having to write essays in composition class at school and such. The elementary school I went to was a national university affiliated school with a lot of events on the yearly school calendar, for which we always had to write essays about our impressions of each event, and I hated that. Also, I wasn’t good at the exercises in Japanese language class where we had read and then write summaries of the meaning in passages from books. But, at the same time, I will never forget how interesting it was when the teacher showed is a scene from a children’s book and asked us to write about the feelings of the characters in the scene. It was the famous scene from an illustrated Japanese children’s book of the Russian folktale The Turnip , where the old man and his wife and their animals like the mule all get together to try to pull a huge turnip out of the ground. I suddenly got inspired by that assignment and ended up writing several versions to turn in to the teacher.

- When did you have your first encounter with theater?

- The principal of out middle school was a leading instructor in the high school theater world and he had us compete in a yearly arts festival with plays that each class put together by themselves. In my second year of middle school I suddenly got inspired and got all 40 students in our class to work together on a production of The Phantom of the Opera .

- That was certainly a big work to start with! (Laughs)

-

On the TV programming page of the newspaper, I had seen the listing a broadcast on the Sunday Foreign Film program of the movie

Phantom of the Opera

and felt strongly attracted to that title. My parents were very strict and would not let me watch any television after 9:00 in the evening. I asked my mother what kind of a story it was and only got a very short answer that it was a story where a chandelier falls (laughs). But, that sounded awesome and ended up getting me even more interested in it. They didn’t let me see the movie but I was able to read the original story and read the synopsis on the video jacket and look at the pictures of the movie scenes, and that set my imagination working so I was able to write a play in no time. After that, there were some fight with my classmates over it, but in the end everyone worked on it in a festive mood. We even made a chandelier and had the scene where it falls, and we had our teacher sitting right under it when it dropped (laughs).It was about a year and a half after that that I finally saw a Geidan Shiki production of the musical Phantom of the Opera , as I watched it, it was with a director’s eye; saying to myself, “That is something we were able to do, but this scene is something we couldn’t have done.” Or, “So that is the [stage] device that makes it possible!.

- Did you have more opportunities to see stage performances after that?

- No. About all I was able to see were TV broadcasts of stage performances. I still remember [the broadcasts of] Steven Berkoff’s productions of Salome , The Metamorphosis and The Trial when they came to the former Ginza Saison Theatre. Our parents were really very strict until I was in middle school, so I was basically forbidden to watch any theater performances or movies or to read mangas . As I entered my rebellious period in high school, this prohibition was gradually lifted. And after it was, I began reading book after book at the library. I read all kinds of things, from pure literature to mysteries. What I got into most of all was the author Ryunosuke Akutagawa. I was particularly attracted to the mysterious nature of one part of his novel Kappa that was in one of our supplementary literature textbooks, and after that I became more interested in the author Akutagawa himself than the stories and I began reading things like critical studies about him.

- In high school you were a member of the school drama club, weren’t you?

- Yes. I went to a consolidated middle and high school girls school, and at first there was some conflict with students who thought I was impertinent and acting more mature than my age. With a high school drama club like ours there were lots of girls who wanted to perform on stage as actors, but I was more interested in directing and would take on the peripheral stage work, so I gradually became more accepted by those around me for that. Our school had other school programs that conflicted with the national drama club contest, but our drama club had two occasions a year to present our productions to the student body, at our school’s annual culture festival and at the performance to send off the graduating class. So, in my first year of high school I was able to write and direct an adaptation of Kappa . Then, in my second year I was able to write and present my own original play for performances.

- What type of play was it?

- I am embarrassed to say, but it was a story about a girl personified as a steam locomotive who finds out she is about to be taken apart and scrapped, so she runs away to find the former engineer who used to drive her. I was a bit of a locomotive and railway fan, so I brought all of that personal hobby interest into the story.

- To do a story about a locomotive at a girls school, I would imagine there was some opposition within the drama club, wouldn’t there? (Laughs)

- I had a tricky plan to avoid that (laughs). I used devices like cute costumes and elaborate rhetoric in the development of the drama. I knew that I would have to do something extra to convince the club to do it so I could continue my reign as writer-director. In our school’s culture festival the individual presentations were all judged by a point system, and somehow my play managed to win the top award. For the culture festival in my third and final year of high school, a wrote a play as a sort of contemporary adaptation of Phantom of the Opera as a story about a plastic surgeon with a multiple personality syndrome and an unsuccessful actress who wants to get a face fix.

- After that you studied in the theater arts course of the College of Art of Nihon University.

-

Yes. I was one of the students of the first year the course was offered. I liked writing but I wasn’t yet thinking that I was determined to become a professional writer in theater. In high school I had written short stories for fun, it never went beyond just having a few people around me read what I had written. Unlike short stories, I thought the plays had to be staged and because of that aspect I might have felt that there was more possibility of the work developing into something larger, but to tell the truth, I really didn’t think about it that seriously. After my mother died, my father told me that, watching their daughter going on to study theater in university, they had thought that I would probably become discouraged about doing theater when I started studying it as a profession. He told me that at that time, they had seriously discussed between themselves what to do when I reached that point. As for myself, I never really became discouraged when I learned that there was some theater that wasn’t interesting.

- You must be the type that is determined from the start to walk your own path (laughs). Anyway, in your third year at university you started your own theater company Paradox Constant. Would you tell us how that came about?

- From our second to fourth years at university one of the classes involved has students from the various courses of playwriting, directing and acting get together to create and perform productions in what was called “comprehensive theater training.” During that training, we were able to use the rehearsal/performance space called the “black boxes” that wasn’t normally made available to students. I fell in love with that space at first sight.

- What kinds of productions did you create in that training course?

-

Usually they would use existing plays by representative Japanese playwrights like Minoru Betsuyaku or Juro Kara, but I wanted to do a play I had written myself. To do that however, it had to be something that could convince the professor and the other student’s that it was worth doing. So I had been searching for ways to convince them, just like I had with my high school drama club. When you encounter stories about historical figures or incidents, there are times when some of the facts make you think, “What is going on here,” and leaves a nagging question in the back of your mind. That nagging question often becomes the point of departure for a play. Something that aroused a question in my mind like that was a TV broadcast of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra that my mother was watching on the national NHK station at the time. When I learned that it was an orchestra with a long history going back over a hundred years, which meant it was active through Germany’s Nazi era, it made me wonder what it was like during World War II. When I researched it, I found that through the War it had still had a mix of Jewish and Aryan musicians as its members. That made me think that there must be some dramas to be found it that situation and I began to read a few more books on the subject.Usually, when taking a subject based in historical fact, you begin by creating a chronology and map of the relationships of the characters involved, but in my case, I don’t necessarily do such thorough historical research like that at first. Rather, the feeling is that once I decide who the main characters will be, the story begins to start moving based on those characters.

- You mean that you don’t begin by deciding on a central theme and the way the story will develop?

- Right. I begin by deciding what the main characters will be, based on the number of actors we have that can be used and how they can be interconnected. Usually, I don’t know how the story will play out myself until the very end. The important thing is what “dialogs” I can create from the encounters that result when the characters that I have decided on are brought together. First, I test the waters by putting two characters together and watching to see what kind of conversation will emerge and then write it down.

The way it generally goes is that I don’t have the characters start talking in line with a set of situational conditions I have laid out for them. They already know the essential points that need to be covered in the scene’s dialog and how the story will develop, so I just listen to what they come forward with natural and I write it down, letting them teach me the way they feel it would go. So, I just keep writing what they say down, not knowing what the conclusion will be. Finally, a point may come when it reaches a [fitting] conclusion. That is the way I write. And, as I am writing down the things they say, I don’t ever stop them by saying, “No, that’s not it,” and have them start over. .- Then, did the work about the Berlin Philharmonic that you created in your training course become the spark that led you to launch Paradox Constant?

- After the training course, there were some people who said they wanted to continue participating in my plays. And since we knew it would not be easy for us to create stages after we graduated, I just thought that it might make sense to do what we could [start a company] while we were students. I had never really had any idea of what a company would mean, but when we contacted a sales company to ask them to handle the ticket sales for our first production, Kami wa Saikoro wo Furanai (God doesn’t play dice, 1998), they said that we needed to give them our company name. Since the play was about Einstein, I glanced through the materials I had at hand and the two words that kept appearing were paradox and constant, so I put them together to make my solo unit “company” name. That was really haphazard, wasn’t it? (Laughs.

- So, I guess you were attracted to the words paradox and constant.

- Looking back, I think I may have had some attraction to things mathematic. I was always very bad at physics and mathematics, but reading the writings of Einstein that I had on hand, his words such as his belief that mathematics is not a process of solving problems that already exist but a process of finding problems yourself and then working out the answers to them, or his belief that when you find a good way of solving a good problem it is as if the formula already existed, or his belief that mathematics is not discovery but invention, these words captured my imagination and stayed in my mind. I believe that is why I became attracted to these two words paradox and constant.

Still, that doesn’t mean that I wanted to write plays that offered solutions as clean as those in mathematics. It was more like I felt simply that eliminating as much waste as possible was a good idea.- You continued your activities as basically a solo unit for some nine years before you established a company with five male actors, didn’t you?

- Yes. For a while after graduation, I was putting on performances of new works at a pace of about one a year while supporting myself with part-time jobs. When I think back now, I really wasn’t thinking about much at all. I then reached a point where I was thinking this was no good anymore and maybe I should take a special seminar in scenario writing, but when I wrote a play Three-hundred Million Yen Incident (2002) about the famous theft incident and staged it with ten actors, it was well received, and that started me writing plays purely for all-male casts.

In 2007, one of the actors who had been acting in all my plays until then, Yutaka Ono (present member of Paradox Constant), suggested that I make a theater company, and since I couldn’t think of any reason not to, I invited four actors who were regulars in my production and established us as a company. Our first production after that was Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal (Tokyo Saiban) .- Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal became one of your representative plays, which has been repeatedly re-produced in the years since. Would you tell us about how it was created? Why did you choose that subject?

- In fact it was a request from a regular viewer of my plays. At our performances, I always hang around in the audience area acting partly as a guide, and one person who had been to see several of our plays came up to me and said he would like to see Paradox Constant do a play on the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal trials. That is where the idea came from.

- Tokyo Saiban is the common Japanese term for the International Military Tribunal for the Far East held by the Allies at the end of World War II to put on trial and punish war criminals of defeated Japan. On trial were 28 “Class A War Criminals” like Hideki Tojo who were accused by the Allies of leading Japan into war. It is a subject that could conceivably involve countless characters, so what made you choose to focus on the five Japanese defense lawyers?

- It was the first production we staged after forming the company, so I decided first of all to make it a play for all five of our members. Since many of my works take their subjects from historical incidents, it leads to misunderstanding, because in fact I always had a poor knowledge of history and in the case of the Tokyo Tribunal, Hideki Tojo was about the only figure I knew of. But, when I began researching the subject, I learned that there was a team of Japanese defense lawyers. Of course a trail natural has defense lawyers, but for some reason I had formed in my mind the image that there was no defense. Since Japan had been defeated, I thought that America and the other victors, the Allies, had simply held the trials and sentenced the accused as they pleased.

The surprise of learning that was not the case became the “catch” that caught my interest, and then as I researched further, I found one interesting fact after another, such as the fact that the representative of the defense team had been the legal advisor to the Imperial Army, and that he had been able to participate in the trials even though he wasn’t licensed as a lawyer, and that the son of the former Prime Minister Kouki Hirota was serving as a aide. These facts led me to choose as the characters for the play the four main counselors for the defense and one interpreter.- You chose a place in the court as the stage setting, with only the defense lawyers presenting their arguments to the unseen and unheard tribunal judges and prosecutors. How did you arrive at that idea?

- In the actual Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal trials there were an extremely large number of recesses and breaks in the proceedings, so I thought at first of having the play set in a front chamber of the court. Since one of the lawyers had an ambulatory handicap and was confined to a wheelchair, I thought of having the discussions take place between him and the other lawyers of the team when they returned to the front chamber each time the court went into recess. But, because the original request I had gotten from the member of the audience that sparked this play was that he wanted to see us stage the trial, I rethought the setting and decided that I should depict the actual trial proceedings and not the recess discussions. Also, since none of our actors spoke English fluently, I decided to use the device of having an interpreter telling the defense lawyer team in Japanese what the judges and prosecutors had said and then have the team discussions proceed from there solely in Japanese.

- In 2015 (the 70th anniversary of the end of WWII), you wrote your latest work, The Diplomats , on commission from the Seinen-za theater company, which is a play that could be called a prequel to Tokyo Saiban . It is a play in which the foreign diplomats who would later go on trial a Class A War Criminals reflect on how it came about that Japan decided to go to war and what happened along the way to the country’s eventual defeated. In this play, the central character is Japan’s Minister of Foreign Affairs at the end of the war, Mamoru Shigemitsu. What was the creative process that led to choice?

- From the various discussions I had with Seinen-za about what angle to approach the War from at the time of the 70th anniversary of its end, the decision was made to focus on the diplomats who had been at the forefront of negotiations and dealings with the foreign powers in the time leading up to during the War. The starting point was to present the grave fact that Japan had lost the War. In the process of researching the records that exist regarding the words and actions of Japan’s politicians at the time, I found that it was the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mamoru Shigemitsu, who had taken a very strong position that even though Japan had lost the War, the country would not let itself succumb to the will of the conquerors without a say in its future, so I decided to make him the main character. For the other characters in the play I chose people who had differing positions and views from those of Shigemitsu, and also figures who served as Shigemitsu’s subordinates.

- Why was that?

- Isn’t it true that when men are in the company of classmates or friends they have a tendency to depend on their kindness and sympathy? I thought that in order to show Shigemitsu’s strength of will it would be best to show him in situations where he acted as a strong leader of people and in situations where he would battle with those who opposed his positions. So, I chose people who were in those types of relationships with Shigemitsu and positioned them as characters in the play.

As I said earlier, I usually write my plays based on the [spontaneous] conversations that occur between the characters I have chosen and the relationships that exist between them. I believe that that kind of “battle of words between people (conversations) is the essence of theater. I listen to their conversations and let them lead me on until I feel that something is about to be revealed, or until I hear something that makes me feel, “This may be it.” If the conversation is flowing well, I go along with it, and when the conversation falters and reaches a dead end, I change the members of the conversation. The Diplomats is a two and a half hour play and it wasn’t until it was about four-fifths written before I could clearly see the conclusion it was leading to.- It would seem to me that, even when given the same situation, the variations in the resulting conversations between different pairs of people would be limitless, wouldn’t they?

- If you lay down a general direction of a story’s flow by deciding who will bring in what information in the early, middle and closing stages of its development to spark a conversation, I believe that you can whittle down the possibilities for the “right” conversation (dialogue) to one or two patterns. After that, I may be making intuitive judgments regarding things like whether the characters in each scene are feeling comfortable or are feeling agitated.

- I feel that one of the appealing things about your plays is that there is a highly refined and articulate feeling to the lines your characters speak, so it seems a wonder that such lines come out of this creative process that you have just described.

- That kind of refinement in the language you describe is not something that I strive for deliberately. To me they are simply the lines that I feel are necessary. However, I do believe that in a play, and not just in the dialogs or conversation, it is best to remove anything that is waste, or superfluous. So, in the story’s development, I am always thinking about who is the best person, or what is the best relationship, to which the baton can be passed on most easily and simply.

- Do you have any particular wish or ideal concerning how you want to depict people in your plays?

- It isn’t anything as noble as an “ideal” but I think I am usually depicting people who are determined never to give in no matter how harsh they situation may be, or people who say they absolutely won’t let themselves die. I don’t remember what the exact cause was, but at some point I found that I had come to the conclusion that scenes where a character dies on stage were corny. So, to make sure that may plays don’t get corny, I don’t want to have characters dying on stage if possible. I guess that is why I came to depict characters with a “no matter what happens, I’m not going to let them kill me” attitude. Also, in order for me to write about a person, I have to come to like that person, and I don’t like people that I can’t feel respect and love for. I believe that is also something that influences the type of characters I write about.

- In terms of writing, is there writer or mentor that has especially influenced you?

- It was after university that I started reading plays seriously, and among Japanese playwrights, I read a lot of the works of Hideki Noda. Besides that, I read foreign plays like Amadeus and 12 Angry Men , but I can’t remember any writer or play that made a really strong impression or influenced me especially.

- I feel something in common between your writing style and the orderly and methodical style of foreign plays in translation [in Japanese].

- Speaking of translation writing style, I think I have been influenced by the style of the movie subtitle translator Natsuko Toda. If I don’t read the subtitles I don’t feel as if I have seen the movie, and especially with Toda-san’s subtitles, the always fit perfectly in terms of both the sound and the visual appearance of the words. I found them to be exceptionally good. With novels as well, I like translations that are firm and tight, and in contrast, when I read new translations that are deliberately made easier to read, I get annoyed. So, I guess you could say that Toda-san’s dialogs are the roots of the “conversations” in my plays (laughs).

- Most of you or performances are not staged in traditional proscenium theater spaces. Is that something you particular about?

- I guess I like small spaces that feel condensed. I am drawn to spaces that feel old with raw concrete and metal sticking out, and the hardness of straight lines. It is partly because that kind of space goes well with my plays, but also there is the fact that ever since my student days the budgets for my productions have always been very tight and we were never able to make elaborate sets or stage art. So, I thought it would be good if the space itself was eloquent. As a result, there are a good number of cases where the play and the theater space are so closely connected that they are really inseparable. I don’t think Tokyo Saiban would have taken the form it has now if it wasn’t for the pit Kita/Kuiki theater space (closed 2015) where we first performed it. And with Kaijin 21 Menso (The Monster with 21 Faces, 2006) about the perpetrators of the Glico Morinaga case, when I found spaceEDGE in Shibuya, I knew the moment I saw it that I had found the perfect space for the play.

- Both of those slightly asymmetric free spaces that have bare concrete walls and high ceilings that go up two floors. That kind of space seems to accentuate the flesh-and-blood presence of the actors.

- I agree. It may not be exactly right to say that the stage belongs to the actors, but I have the hope that during a play the audience will look only at the actors. In order to make the actors stand out and the audience concentrate completely on them, I feel it is best that there be nothing soft except the actors’ bodies. I believe that I unconsciously elect such spaces and places.

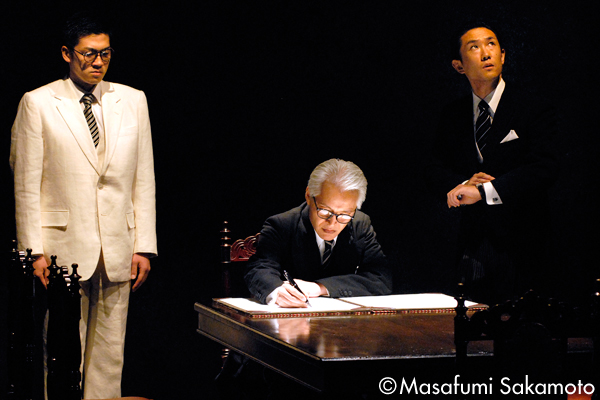

Paradox Constant

performance of Tokyo Saiban

(Dec. 22 – 31, 2015, pit Kita/Kuiki)

Photo: Ryuta Watanabe

Seinen-za performance of The Diplomats

(July 31 – Aug. 9, 2015, Seinen-za Theater)

Photo: Masafumi Sakamoto

Moegi Nogi

Theater as a battle fought in words

The world of Moegi Nogi

Moegi Nogi

Born in 1977 in Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture, Nogi was among the first class to graduated from the newly established playwriting class of the Theater Course of Nihon University College of Art. Her interest in playwriting was aroused by a movie she saw in her second year of middle school. In high school she wrote plays and directed for her school’s drama club and continued to study theater and playwriting at Nihon University. In 1998 she formed the theater unit “Paradox Constant” and performed her play Kami wa Saikoro wo Furanai (God doesn’t play dice). With the premiere of Tokyo Saiban in 2007 the unit formally became a theater company. Taking the framework of historical facts and incidents, Nogi writes vibrant conversational theater works with bold imagination. She is known for her plays with highly intense dialog that springs strong human relationships. Among her representative works are Kaijin 21 Menso (The Monster with 21 Faces, 2006) about the perpetrators of the Glico Morinaga case; Intellectual Masturbation (2009) about the High Treason Incident; Showa Restoration about the night of the failed February 26 coup attempt of 1936; and The Diplomats , written for the Seinen-za company and depicting events occurring from prior to the Pacific War up until the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal from the perspective of the diplomats who would then be put on trail as war criminals.

IInterviewer: Kumiko Ohori

Related Tags