- May I begin by asking what got you into dance originally? Where there any specific experiences from your childhood that that connect to the dance you are doing today?

-

I was a real showoff who liked to stand out when I was a child. I just love performing in front of people, and I was always singing and dancing. When our relatives would gather at New Year’s we kids would get little [monetary] tips if we did something in front of everyone. I think I was about five or six years old when I did my first show. I dressed up in one of my mother’s dresses and sang and danced to songs by the pop stars Akina Nakamori and Miho Nakayama. That was an important first event for me. Also, I took lessons in traditional Japanese dance ( Nihon buyo ) for a short time. When I was still very small, I apparently told my mother, “I wanted to do dance!” And there happened to be a dance teacher in our neighborhood, so I went to have lessons there. But, another thing that I got into even more was Ohayashi (festival costume dancing to flute and drum accompaniment), which I did for about ten years as a child. In the town of Tachikawa (Tokyo) where I lived there was a festival with floats that we danced on wearing a Hyottoko (comical man character) or fox mask, and it always felt so good for me to do that.I loved being seen [dancing] and receiving tips; I guess I wanted to be a showgirl (laughs).

- When we speak of dance, there are of course many different types of dance. What attracted you to street dance?

- I began to develop an interest in street dance when I was in middle school, I think. In Tachikawa, there is an American military base and around that time some hip hop shops run by African-Americans had begun to spring up. But, going to the shops or clubs to dance was something that proper kids didn’t do. It tended to be the bad boys we call yanki who hung out there. I though the dancing was cool and would have liked to learn it, but it just wasn’t the kind of place I could go.

It was also around that time that I started to listen to foreign music, and I would do imitations of Michael Jackson and Janet Jackson and at home I would secretly practice dancing hip-hop. When I did, I would wrap myself in one of my mother’s scarfs and put on makeup (laughs). Looking back, I realize that the artists I wanted to emulate were all female artists. When I was four or five there was nothing strange about wrapping a scarf around my neck when I danced, but when you reach puberty, you begin to sense that that kind of thing is a bit unnatural. So I would go up on the roof of our building with a cassette player and a set of headphones and look up at the starlit sky as I danced with no one knowing (laughs).When I think back like this, a lot of the tings I remember are embarrassing to me now. It may be that those kind of really small things that I was unable to talk about or argue back about when I was a child are things that I am finally able to say in my works with Tokyo Gegegay and get them off my chest.- It seems as if your mother’s scarf and the makeup might have had some significant meaning in your development after that. How did your family feel about you and receive your behavior as a child?

- It seemed that they just brushed it off by saying, well our son is a little bit different from other boys. It was only my grandmother, who herself was doing hula dancing at the time, that would say that it was OK for me to be doing the things I liked, and she was very supportive. So, I guess you could have called me a grandmother’s child.

- Did you ever study street dance under some teacher?

- In fact, there was a time when I was intent on becoming a singer, and for a while I had a contract with a recording company. Until then, I was self-taught in both singing and dance, so they had me do voice training and take dance lessons. But, I found it so boring going through dance lessons from the basics. I hated being told to do this and do that, so I quit after six months (laughs).

So, by then I was 20 and finally of the legal age where I could go to the clubs and I started going to the clubs to listen to the dance music and watch the dancers’ shows. There I began to dance hip-hop and I started to do street dance as well. At that time I hadn’t come out yet and admitted that I was gay, and when I would dance with my friends it was in the loose-fitting clothes that boys wore then and the dance routines we did were masculine in style. For about four years I was frustrated, having the feeling, “This isn’t what I really want to do!”- So then you started the unit Tokyo Kids in 2005.

- It happened because I met MAIKO. She really liked the gay culture and bondage fashion, and I was struck by her eccentric sensitivities and thought that I would like to work with her. I felt that if I could do that, I could probably be freer myself and be more like the real me. And in fact, in the process of doing a variety of works with her, I found that my sensitivities and perceptions were rapidly becoming freer. And then I felt that if I had my coming out and accepted openly that I was gay, I could do anything (laughs), and after that my shows became more and more original and unconventional. At first we had five members, but some left, saying that they couldn’t follow the direction I was going, and they later formed the unit “s**t kingz.”

We were active as Tokyo Kids for about seven years, and in the end it was just me and MAIKO. By that time I had decided that I wanted to do all of the creative work [choreography, etc.] myself. At that time, there was a group of kids that I had been teaching at a dance studio since they were small and their skills as dancers had become quite good, so I decided to form Tokyo Gegegay with them. They were like fellow travelers who had been with me for a long time and would accept my eccentricities and my selfish requests. They have never said to me, “We can’t do that!” (Laughs) Now MAIKO is active doing choreography for Kyary Pamyu Pamyu and other things.- So, I guess one could say that, not having what would be called a teacher or mentor in dance, you came to create the works you do today with their unique world of expression based purely on your own various experiences. Weren’t there any artists in other fields like music that you admired?

- Yes there were. It is hard to explain, but I feel that what I do is in sync with Michael Jackson. His Neverland and that longing for a world of fantasy are things that I would have liked to say, “I know where you’re at, Michael!” (Laughs) Maybe it’s pretentious of me, but in my own way I feel I’m in sync with him and his world.

- I would like to ask you know about Tokyo Gegegay. In the costumes, the theatrical settings the choreographing of the movement, etc., your works are full of your unique aesthetic sense and playful spirit. For example, in your memorable first work Tokyo Gegegay Jogakuin no Chikai (Pledge of the Tokyo Gegegay Girls Academy) you all wore typical high school girls’ “sailor” type uniforms, and while acting out a parody of the “pure, proper and beautiful” image expected of high school girls by means of vigorous and radical dance performance. The series of Jogakuin (girls high school) pieces have become the standard performance numbers of Tokyo Gegegay. Street type dance almost always tends toward a competitive style in which the dancers show off their techniques. But your style seems to be unique because of the way you bring in theatrical elements while still creating an air of street dance performance, wouldn’t you say?

- From the standpoint of highly practiced dancers who have mastered one of the existing genres of dance, my choreography is crazily improper and impure. Because, it breaks down all of the accepted conventions of existing dance styles and brings in a mix of all different kinds of essences. Gegegay Jogakuin starts out with a narration that proclaims, “I pledge to be always soiled, slovenly and ugly, and to pursue the path of performance to the end,” and then I proceed to delight in the process of using dance to tear apart all of the accepted values and rules that I had been bound and suppressed by. And in this all, the Japanese word gei (performance, art) may be interchangeable with the English word gay (laughs).

- In the dance you choreograph, especially the upper body movement is amazing, and the expressive power is extraordinary. You achieve an abundance of expression with the arms, hands, neck movement and also the facial expressions. All this makes yours a style that is different from other styles of street dance.

- In the existing styles of street dance, the emphasis is rather on leg movement, but I believe that with Gegegay it is mainly the arms and hands. At the time I started street dance, the teacher at one lesson I went to said the energy of the body circulates around it, and stepping down with your feet causes your arms naturally move in response. Then he told me that in my case all of the movements of my lower body were dead, so I decided at that moment to let it die (laughs). You know, when you are dancing Ohayashi on a moving festival float, it is dumpy and swaying around, so you can’t do steps. So, in order to perform your dance, the basic rule is to stand firmly with your legs apart. That may be why I use the lower body as a base to support the upper body [movement].

- In May of this year (2015), you served as the overall director for the stage piece *Asterisk that brought together most of the top street dance artists in Japan. It was a wonderful grand-scale work for a large stage in which, under the title Megami no Hikari (Light of the Goddess), the storyline and the visual elements were skillfully brought together in a seamless fusion. What kind of idea gave birth to such a work?

- I wanted to try making stories based on dance like those in movies such as Flash Dance and Show Girl . Also, in times like this when there is a big growth in the number of child dancers, the presence of a variety of “stage mothers” coaxing on their children can’t be ignored, so I wanted to include them too (laughs). In fact, the “goddess” ( megami ) in the title is something I borrowed from the “ Arashi no Megami ” (The Storm Goddess), which deals with the complex feeling of Hikaru Utada toward her mother Keiko Fuji. I thought it would be OK to liken the mother to a goddess. It was also a form of homage to those two artists.

- The casting was amazing, bringing together the best street style dancers from around Japan. Although they may classify as street type dances, since each individual or group has its own character and style, I would imagine that the creative process for the work must have been tremendously difficult.

- Once it was decide to do this project, I thought I should be very particular about the casting. So I [senior] dancers I have connections with and friends contacted, so most of the 54 participating dancers were people I already knew. First I shared with them the basic storyline I planned to use, and when the plots for the different scenes were roughly finished, I worked in partnership with a professional composer and started quickly making and deciding on a lot of the music. Bach when I was intending to become a musician [singer], I used to do the music and lyric writing myself, so as I decided which dancers would be in which scenes, I began researching videos [online] to find out what kind of music each of them preferred, so that I could put together a program of music that would enable each of the dancers to perform in a way that brought out the best in them.

For the dozens of choreographed scenes, I divided the dancers into 20 units and had each unit rehearse separately. And, since I was constantly moving between the different studios where each of the units were to do the choreography, it was really a tough job. Then I fit the scenes together like pieces of a puzzle. From one month before the performance date, we began the overall rehearsals, but it was really difficult to find times when everyone could get together. So, it was only then that the participating dancers probably got a picture of what the whole thing would look like. For seven months I concentrated exclusively on this project.- When I saw the performance, I was certain that you must have worked at least that long on it. Seeing your stages, I feel that you are very skillful at grasping the visual aspects of the performance space and the sense of time. Each scene has fresh visuals and the tempo and groves with which you change and develop the sound has a great feeling.

- When creating a work, it is very important for me to have visual “pictures” in mind. First I think about the kinds of costumes and where the dancers will be and how the music will make the “picture” develop. Thinking about things like that helps me get a mental image of the visuals in terms of the composition of the dance and the formations the dancers will take. From the beginning, I have thought that I want to express the world I envision totally, in all aspects of the staging. In the case of Megami no Hikari , I felt that in a sense that dream came true, and all of the things I had been doing until then came together in what for me was a personal masterwork.

- Personally, I very much liked the two high school girls in the unit Lucifer that you directed. Of course they had outstanding technique, but besides that they had a sense of beat that comes from the very core of their bodies, and what’s more, that gave them a natural visual appeal. I was truly surprised to discover that people like them exist in Japan.

- I am extremely happy to hear that. They are about 17 and they have been competing in dance battles and contests that measure dancers’ skills. When I first saw them dance, I thought that there were kids that could dance like that at their young age, there was no need for me to dance anymore. That is how much they amazed me. Since I had been wanting to add fresh new talent like theirs, I had them participate in Lucifer.

- That project was produced by Sachiko Nakanishi. How did you come to meet Nakanishi-san?

- When I was in Taiwan, Nakanishi-san came to see me with an offer. She had seen a performance of Gomiyashiki by the group Vanilla Grotesque that I led until 2012. The costumes for that production were made completely of trash, using things like thousands of empty can tabs fastened together with hair clips and things like flowers made of tissue that were fastened all over to make a dress like one out of My Fair Lady (laughs). That was the result of having to use our imagination because of our lack of budget for the production, and the idea came from something that an older gay friend told me about the “cheap gorgeous” costumes used in the drag queen world.

It seems that from that time Nakanishi-san had invited me to work together with her, but I didn’t remember having been told that. When Vanilla Grotesque performed in the 2014 *ASTERISK program, the sight of Nakanishi-san when she stayed late and was cleaning up trash in the studio brought to mind an image of my late grandmother. So, I thought, if my grandmother is telling me so, I have to accept the offer (laughs).- In 2015, the new “DANCE DANCE ASIA” (DDA) program of the Japan Foundation Asia Center got underway on a full scale. It is a program to support exchange and collaborations between dancers and dance groups within the Southeast Asia region, with “street dance” as the key words; and this year (2015) 12 Japanese dance groups were sent to five countries in Southeast Asia. You participated in this program as well. Where did you go?

- I went to Manila and Bangkok. It was the first time for me to visit these cites, and I saw barefoot children there asking for food. Seeing the gap between the rich and the poor was a real culture shock for me. I just love children, and I had the chance to play with children in a back-street sort of area in Manila. When I taught them a bit of dance I had choreographed for them, they really got into it and I felt that we received a great welcome for what we were doing.

- How was the response in Manila and Bangkok?

- It was interesting and fun to perform there, because being in a situation free of preconceptions, the audience’s response was very straightforward and enthusiastic. In Tokyo, as soon as we come out on stage, people are thinking, “Oh, no. This is going to be something weird.” I always wonder, why can they think that the minute we stand on the stage, even before seeing what we do? (Laughs)

Although we weren’t able to do it in Manila, in Bangkok I wanted to have a chance to bring children up on stage to perform with us, so I asked Nakanishi-san if she could arrange it. So, we were able to have a practice session with about 30 kids from Khlongtoei, one of the biggest slums in Thailand. We were told by the Japan Foundation people that they might just leave in the middle of it, or they might not come to the next practice session, but all of them came every day. Rather than not showing up, we found that they would come early and start practicing on their own, and some of the kids even said that in the future they want to be dancers, so I thought it was great. By the way, in the DDA Tokyo performances there was a bicultural young person from the Philippines participating as a dancer. That person’s physical abilities were amazing.- In recent years, a number of street dance associations have been formed and street dance (contemporary rhythm dance) is included as one of the types of dance being taught at elementary and middle schools in Japan where dance is a required subject. Trends like this show that the environment for dance is changing. How do you feel about these changes in the dance environment?

- There are a growing number of dance studios today, and the number of children who want to study dance is also growing. There was a period when I was teaching lessons at dance studios, but after some time, I realized that in the process of simplifying the choreography so that the kids could learn it easily I was getting away from the choreography that I really wanted to be doing. That was a very bad feeling, so I eventually quit teaching there. I still do workshops on a one-off basis, but when I do, I say let’s all share in the choreographing, so the participants are able to change my choreography. I feel now that it is OK if we do these workshops in a party-like atmosphere where everyone can have fun. There was a period when I was participating in dance shows while working part-time at shop that sold rice balls, but now I am getting offers from abroad from people who have seen videos of our performances on the Internet, so indeed, the dance environment is changing.

Recently I had the opportunity to make a guest appearance at the national contest for middle school and high school dance clubs, and I found that all of the young students doing dance were great kids. They were bright and fresh and were full of enthusiasm. Among them there must naturally be a few different types, however. The environment for children tends to be quite confined, being mostly between home and school. But, doing dance expands their community, and I think it will be good if the dance experience expands their world and shows them that when they get older they will be in a world where there are many different kinds of people. I am somewhat skeptical about the fact that dance has become a required subject in the schools, but I think that kids who come to like dance will continue in it, and since I believe that they will want to learn the way things really are, I feel that it may be a good development if it widens the gateway to dance.- Finally, I would like to ask you if there are any particular things you would like to do in the future.

- Next year I want to do something new and interesting with Gegegay. One thing I would like to do is stage something like a haunted house attraction.

- Well, it seems to me that Gegegay already has quite a haunted house aspect (laughs).

- You’re right about that (laughs). I’d like to use something like a vacated school building to do a kind of tour performance where the audience moves from classroom to classroom and in each one there is a different show attraction. Some people may start in the music room and others from the art room, and eventually they all end up in the gymnasium for show. Once I was producer for a summer vacation project for sixth graders where I was the leader and we made a haunted house attraction in the local children’s facility for the neighborhood kids to come and enjoy. In the facility we used cardboard to section it off into cubicles where different scary figures would appear. I think having children come in and enjoy the thrill of screaming and laughing has always been my original point of departure. So, I would definitely like to do a haunted house plus dance type of event.

About DANCE DANCE ASIA – Crossing the Movements

Interviewing Sachiko Nakanishi (by PANJ editorial desk)- “DANCE DANCE ASIA (DDA) – Crossing the Movements” is a jointly sponsored and organized program of the Japan Foundation Asia Center and PARCO. You, Ms. Nakanishi are the one who has been responsible for PARCO’s program of street dance events. And now you are the producer of DDA. Initially, what were the concerns that led you to begin involvement in producing street dance events?

- Around 2007, an actor of France’s national comedy theater company the Comédie-Française recommended that I see a street dance version of Romeo and Juliet that was playing at the time, so I went to see it. I had absolutely no interest in street dance at the time, so I went to the performance with no expectations whatsoever. However, what I saw was dance that was being performed very well and in a way that I found quite appealing in itself. The dance looked cool and the stage art was stylish, all of which interested me greatly. And most of all, the reception of the audience was so enthusiastic. When the performers danced to classical music, I found it to be so very refreshingly new that even a person like me who had admittedly been prejudiced against street dance prior to that was absorbed by it. The audience ranged widely from young people in their teens to the elderly, and they were all enjoying the performance from their own individual perspectives and experience. That made me feel that I would like to introduce this kind of performance to Japanese audiences.

- What was the status of street dance in Japan at that time?

- The scene consisted mostly of dance battles and contests where the dancers competed with their individual techniques, and there were just a handful of groups like Wrecking Crew Orchestra and Dazzle that were doing stage performances. When I told people that in Europe there were artists creating works that fused contemporary dance and street dance together in interesting ways, street dancers would say, “but contemporary dance people can’t really dance,” and contemporary dance people would say, “there is no artistic expression in just spinning around on the floor.” So, I realized that it would be very difficult to get the dancers of the two genres to respect each other and work together on projects.

- Then in 2013, PARCO produced the dance entertainment program *ASTERISK at the Tokyo International Forum that brought together many street dance performers. Eight groups and 121 dancers participated with direction by Tatsuya Hasegawa of Dazzle and scriptwriting directed by Koichiro Iizuka.

- That’s correct. From 2012, we had been producing Dazzle’ and Umebou stage performances. Although there was still a need to polish the quality of the pieces performed, the *ASTERISK program brought together dancers who were performing seriously and full of the pure energy. That energy felt like the same magma just before the eruption of the small theater boom in the 1980s. And it was bringing in a large new audience of young people who don’t usually come to stage events. Hearing that the Japan Foundation was about to launch its new Asia Center, we were able to organize a joint program. Today, street dance is very popular in Southeast Asia and we all agreed that it would be meaningful from the standpoint of exchange and creative collaborations in the Asia region if we could initiate a program of stage performances.

- Had you done surveys about the status of dance in Southeast Asia prior to launching the program?

- We had done surveys in five countries in the region. We interviewed local opinion leaders and we held meetings concerning technical aspects and production. We also went to see actual performances. In most of the countries the street dance scene was dominated by dance battles and contests as in Japan, but the one exception was Vietnam, where the German Culture Center and Institut Français, etc. were supporting activities and they had successfully created stage works using locally based German and French directors and dancers from Hanoi.

- Would you give us a brief outline of the DDA program?

-

DDA aims to link the countries of Asia through street dance and it is a large-scale program that is planned to continue until 2020. The first project sent leading street dance groups from Japan to four Southeast Asian countries (Manila in the Philippines, Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia, Hanoi in Vietnam and Bangkok in Thailand) in January through March of 2015. The second project visited Jakarta, Indonesia in August. There, 12 groups

(*1)

, three from each country, held performances and workshops in several localities. A documentary movie was made with scenes of the local exchanges, and the movie has been released (*2) . Our hope is that the dancers participating in the DDA program will learn about the countries they are sent to and that seeing the videos resulting from the program will stimulate interest in Southeast Asia through the medium of street dance.*1 90’s, BLUE TOKYO, Memorable Moment, Moreno Funk Sixers, PECKLESS, Ped Print, s**t kingz, TAPDANCERIZE, Time Machine, Tokyo Gegegay, Umebou, WRECKING CREW ORCHESTRA

- Would you tell us about the local reception and response to the program in the region.

- The partner for the workshops are the local Japan Foundation branches in each of the countries, and they serve as coordinators for finding exchange parties based on the situations in each country and the groups that are sent. The participants vary from top-level street dancers to children.

The four middle school and high school students that took part in the Tokyo Gegegay workshop in Bangkok surprised us with their dance performances that were bursting with energy from head to toe. The young dancers who participated in the Jakarta workshop were also full of pure energy that was amazing to see, and they said that they wanted to express themselves through dance.- What are the DDA plans for the future?

- There are performances scheduled at the Setagaya Public Theatre in Tokyo in October by groups consisting mainly of the Japanese groups sent to Southeast Asia and groups invited from the Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand. Also, in November, there will be a special stage performance by Japanese and Southeast Asian dancers born in the 1990s titled “A Frame.” The three performers will be oguri of s**t kingz, American dancer and choreographer Julian Meyers who has performed as a back dancer and choreographer for Janet Jackson, and Takuro Suzuki. Not only will we be inviting Southeast Asian and Japanese artists, we will also continue to promote exchanges through creation of collaborative works.

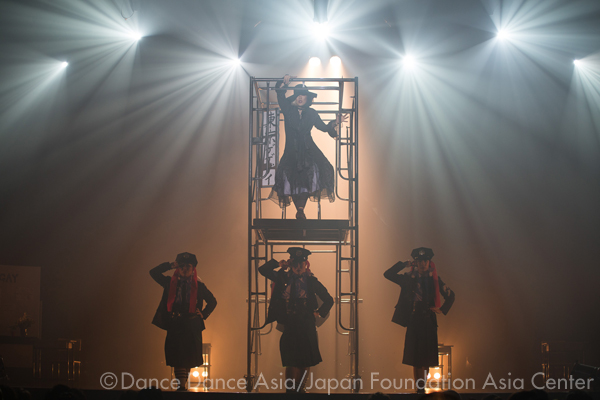

Performance of Tokyo Gegegay at “DANCE DANCE ASIA” in Jakarta

(c) Dance Dance Asia/Japan Foundation Asia Center

Munetaka Maki (MIKEY)

MIKEY of Tokyo Gegegay The quest for absolute release

© Hirohisa Aoyagi

Munetaka Maki (MIKEY)

Munetaka Maki (MIKEY) is attracting attention today for his pursuit of new types of expression in stage performance based in street dance but different from the type of technique-oriented street dance displayed in dance battles or contests. As the pioneers of what he calls a “bizarre mental world” is his group Tokyo Gegegay present theatrical works that overwhelm viewers and free them from the constraints and suppression of daily life. The leader of this group is the charismatic dancer, choreographer and director MIKEY, who is known for the unique aesthetic sensitivity that colors his shows and his collaborations with MAIKO—known as the choreographer for Web sensation Kyary Pamyu Pamyu—performing as the unit Tokyo ☆ Kids and for his “Vanilla Grotesque” productions that children participate in.

Tokyo Gegegay

https://www.tokyogegegay.com/

Interviewer: Tatsuro Ishii [dance critic]