- We are told that you grew up in the Magome district of Tokyo.

- Yes. Around the time I started elementary school my family moved to share my grandfather’s house in Magome. My grandfather’s house was in the middle of the area that had formerly been known as “Bunshimura” because of the concentration of homes of prominent authors and artists, and on the street just behind the house were the old homes of the authors Shiro Ozaki and Chiyo Uno, and there were stone monuments to other famous literati around the neighborhood. Even though I hadn’t read their works, when I saw their books or their names in the school library, they would conjure up images of the homes or the nearby backstreets of our neighborhood. [Laughs] You could say I was a strange child in that way.

- Did that lead you naturally to an interest in writing?

- It wasn’t just the place I was living but also my family environment. My mother had done rhythmic gymnastics in her student days and liked contemporary dance, and she loved making things with her hands, in crafts such as metal carving and pottery. My grandfather was the type who spent his time in his library writing things, and it was my job to carry tea to him there. For a while I studied ballet at my mother’s suggestion, but I was the type who would get the broken bone when I collided with another child in practice (laughs). So, I guess I naturally became a bookworm. But, what I first fell in love with was not the novels of the famous authors but the detective series “Shonen Tantedan” (Child Detective Group) of Edogawa Ranpo, the Sherlock Holmes series of Arthur Conan Dolye and the “gentleman thief Arsène Lupin” series by Maurice Leblanc. It was as if my only reason for going to school was to get access to these books at the school library.

- So, you were truly a literary young girl.

- I just loved stories. When I was little, I would get absorbed in fantasy games with a childhood friends like pretending the bunk bed we were on was a boat that we had to navigate a stormy sea on. On the other hand, when everyone was play in a group, I was the type who would stand off and watch instead of joining in. Since I was like that, even in elementary school I had the idea somewhere in the back of my mind that I would get a job where I could write stories when I grew up. When I was in 5th grade, my teacher saw a picture-story show I had made based on Kenji Miyazawa’s Yamanashi , and that was the first time I really got any praise for my work. Thanks to that teacher, I got the idea for the first time that writing could open doors to the world for me, and I began to get a sense of how to do it.

- What sort of course did your life follow after that?

-

The school I went of for middle and high school was a Christian school for girls and, probably in reaction to my life until then and out of a fascination with the unique atmosphere surrounding the practice of Japanese martial arts, I joined my school’s Kendo (bamboo sword training) club. After a while, I wanted to quit, but didn’t have the courage to say so, and as a result I ended up doing Kendo for six years and even ended up as the captain of the club. But, I also spent a lot of time in the library, reading lots of long novels like Kaoru Kurimoto’s “Guin Saga” series. In middle school I would take existing characters from stories and write new episodes about them. Once a friend and I agreed to write episodes and exchange them every two days. She ended up quitting after just three days, but I could just write on and on, so I kept it up. I liked having someone read what I wrote and I enjoyed the feeling that the characters were coming alive and acting and speaking on their own.Actually, this was a period when there were events that would shape my personality development.

- What were they?

- In my first year of middle school my grandfather died, and in the same period we found out that my mother was suffering from an illness that was classified by the department of health as a serious illness [without a known cure]. For a long time my time was spent between school and daily visits to the hospital. Since no medicine has been found to treat her illness, she is still afflicted by it.

These experiences made me acutely aware that the clock that measure our lives is constantly ticking away. Seeing the way the condition of the people suffering from the same illness affected my mother, I came to realize that fluctuations in a person’s strength and will to live could affect how quickly those seconds ticked away. Thanks to my mother, I learned from a very early age that we never know how long our daily lives will continue unchanged and, therefore, how precious each moment is. And, I believe that this consciousness has a definitive effect on the color of the things that I write.- So, you had life-changing experiences at a young age, didn’t you? Before we begin talking about your writing, would you tell us something more about your initial encounters with theater?

- Yes. After that, since I wanted to become a writer, I decided to go to Waseda University for its literary arts course. As with Kendo earlier, I decided on an impulse that I wanted to do jazz dance, so I also joined the Waseda musical club with the idea that it might be a place where I could dance. It was a club that created their own musicals using scripts selected from ones written and submitted by members of the club. Shortly after I joined the club, I wrote a script while reading a sort of how-to book about writing movie scenarios, and it was chosen. What’s more, there was also a tradition in the club that the writer of the script also did the stage directing. That forced me to make a hasty leap into the world of theater.

I really knew nothing about theater, so I contacted former members of our musical club that had gone on to positions in theater companies like Bungaku-za and Tokyo Kandenchi, saying that I would do any kind of volunteer help if they would let me learn on site about theater-making. Thinking that I would also need to know something about the running of a theater company and production methods, I also got a part-time job at the closest theater to our university, Ado Mizumori’s Mirai Gekijo. I feel that what I learned at that time, not only about theater but also what I learned from working backstage about the very down-to-earth breed of people who were different from most working people in society and the interesting relationships that exist among people in a theater company, were all very important experiences for me.After that I went to see a lot of companies performances, one leading to another as I found them. The first time I saw a performance by the Jitensha Kinqureat’s company at Kinokuniya Hall, there was such palpable joy in the audience as they left the theater, their faces smiling and seeming to glow from within. Having watched my sick mother for years, that sight at the theater of people so full to overflowing with life energy made me fell what a magnificent thing theater could be. Reading a novel can be a moving experience, but what I found at the theater was a very different type of emotional experience, where the group of ordinary people who have come together in the audience by chance can feel the walls between them be thrown open in an instant in a shared experience. I felt that performance by live human beings is an amazing thing. And I came to feel that I wanted to make theater seriously.- That sounds like tremendous motivation to come from a chance experience in doing a musical in a college club.

- Like with my reading craze, when I get absorbed in something the limits disappear. It was the same with musicals. As soon as I got involved in it, I was absorbed by a passionate feeling that even in Japan we could make exciting original musicals! (Laughs) Since I was doing the lyrics to the songs myself as well, I began training myself to seek words in Japanese not only by their meaning but also with an awareness of their potential pitch and intonation. I believe that it was form the experience of that time that I began to develop a sense of how to choose words to express as much as possible within a limited number of lines.

At university I major in literary arts, but I ended up never writing a single novel.- After graduation you were able to continue writing musicals, weren’t you?

- I had connections among people in the musical world by that time and I was able to get jobs writing scripts for commercial-base musicals. However, it wasn’t work that tested my ability as a creative writer as much as it was a case of crafting out a work based on what someone wanted me to write. Eventually, it fueled a desire in me to write contemporary theater plays.

- That is what led you to begin attending the playwriting seminars in Japan Playwrights Association in 2007, is it?

- Yes. I wanted to begin making theater in the small-theater scene, but I didn’t know how to go about it. So, I decided that to begin with I should go to a place where there were other people who wanted to write plays. But at the time, I was working as assistant manager of the Nippori Sunny Hall and I wasn’t able to say that I was going to take a certain day of the week off [to attend a seminar]. I had worked there for four years but eventually I decided to quit the job.

- Your career moves always seem to be determined ones.

- I believe that is due to the strong influence of my mother and her illness. You could call it a case of doing things while you can, but for me it is more a feeling that the amount of time when we are able to do things is always limited. So, there is no time for indecision. I always feel that kind of urgency.

After quitting that job, I began a life from 2007 in which I attended the playwriting seminars while working as a temporary employee at the Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum of Waseda University, where I was involved in publicity work. In fact, however, the experience working at the museum was quite interesting for me. The curators there would talk about long-gone Kabuki actors or actors of the Asakusa keiengeki (Vaudeville-like theater) world as if they were acquaintances they still met often. (Laughs) It was a workplace that gave me a glimpse of the human side of the artists—such as how much they liked to womanize and their personal faults and strengths—rather than critique of their artistic work. I feel that the foundation of what attracts me to write about a certain person, what makes me love a character and motivates me to write about them was formed mostly in my time at the Theatre Museum.- At the Japan Playwrights Association seminars, one of your teachers was the late [master playwright] Hisashi Inoue .

- Mr. Inoue passed away in the spring of 2010, so I was his student in the last year he taught, 2008. Because of one of the works I wrote to submit to the seminar in 2007, I was fortunate to be selected as a member of the group to receive individual instruction from Mr. Inoue. It was not instruction in a classroom situation but an arrangement in which you would receive individual instruction at the teacher’s discretion whenever there was a chance to communicate.

Mr. Inoue was a very busy man, so it was difficult to find time to meet. So, I would go to the performances and such where he would be and say hello and then stand by while he autographed pamphlets in the lobby and listen while he gave me suggestions about what could be changed to improve a manuscript I had submitted for his perusal three months earlier. It might be for just five minutes or so before the performance, but I would make notes about the things he had said as fast as I could before the lights went out in the audience area. Once when I went to hear him give a lecture at the Sendai Literature Museum, I had about 10 minutes before the post-lecture social gathering began to ask him a few important questions. After that, in the train going back to Tokyo, I tried hard to make notes of everything he had said. Rather than being a process of personal instruction, it was more like a year spent watching Mr. Inoue from a distance.- Do you feel that you learned something about being an author?

- It may be true that perhaps the biggest lessons I learned from Mr. Inoue were what I saw firsthand about the way he continued to be active on the front line of his profession as a creator until that age. When I would meet him at a coffee shop in Kamakura to receive advice about my work, in addition to that he would always add something about the ideas behind the things he was currently writing. When he was writing Musashi and Romance , he would even ask me if I thought the ideas were interesting.

The things Mr. Inoue taught me were always very simple. Things like, “Have your characters say things that are said only once in a lifetime,” or, “Once you have shown one of the rules of the world, then proceed to turn it upside down.” He would say the things he tried to do in his own writing as if they were maxims, and I wrote down every one in my notes. But, I didn’t understand the real leaning of those things he said until after I started my own theater unit Tegami-za.In our last seminar, Mr. Inoue said to me, “Use your strength of will to make [each] full day go in a good direction.” But, at that time all I could say was, “Yes.” It was only after my writing career had really begun and I was experiencing how difficult it is at times to keep focused on my writing when I was under pressure that I finally realized that those words he had given me at that last seminar were actually the secret for continuing to be a front-line writer throughout your life. When Mr. Inoue said, “It was only after writing 100 plays that I came to understand something about how to write,” I realized that no matter how long you may work at it, the job of a creator never gets easier, and that continuing to stay on the front line as an author is truly a difficult task.- Are writing stories and writing plays different things?

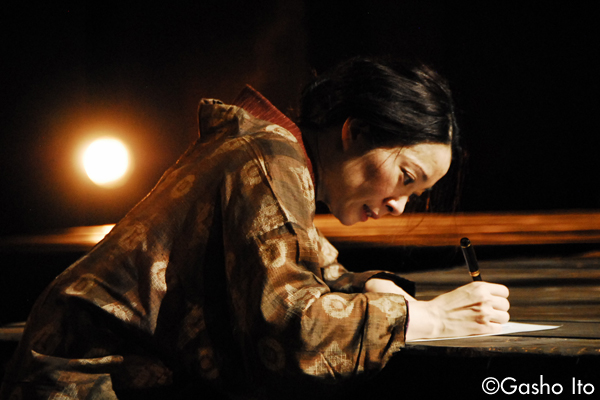

- When I first started writing plays, I thought that I had to try to write everything in the script. However, I gradually came to believe that being a playwright meant being able to write not only the words that are spoken and heard, but also being able to write words that include the actors’ physical presence and the dramatic spaces of the stage, things that can’t be seen and words that can’t be heard. The process of weaving together both the things that can be heard and the things that can’t be heard is truly fascinating. The only tools you have to weave in something that is not verbal are words themselves. But this isn’t a contradiction. I believe that since I began writing plays I have discovered the fascination of using things that can be seen to write about things that can’t be seen.”

- In 2009, you started your theater unit Tegami-za. As the unit’s playwright you are the unit’s leader, and the other members are only a handful of actors. It is a theater unit that uses a different guest director for each production.

- With this unit, my first aim was to put into practice the things that I had learned from my teacher, Mr. Inoue. My biggest motivation for starting the unit was to be able to stage performances of what I wrote, because if you don’t perform your works you won’t get any commissions for more work and you won’t become a playwright. So, the first thing I did was to take a play I had written and visit the Oji Fringe Theater to book a date for a performance the next year, even though I didn’t have a director of a staff decided on yet. Thinking back, it was a crazy approach (laughs).

That day, there happened to be a performance by Roba Shimori ’s company Windy Harp, and after the performance they were doing a café. One of the theater’s people introduced me to the stage art designer Itaru Sugiyama, and after that first meeting I have continued to ask Sugiyama-san to do the stage art for our productions. I also met the actor Takuya Senda, who had been one of the performers that day, and I gave him a copy of my script on the spot and asked him to perform in it (laughs). Now, Senda-san is an important director for Tegami-za. In my case, the desire to do something or the idea for a project always comes out first and then I find the means and the people to help me do it.- Do you not do the directing yourself because you want to concentrate on your work as a playwright?

- To me, directing is a different type of job, and I thought I was capable of doing it along with writing plays. A director is probably someone who can take live people and make actors of them, and someone who can create the theatrical/dramatic spaces themselves. I write plays so that I can have people with that ability take it and work it into something beyond the script itself. So, I have given up the idea of directing the plays myself. However, I am not only doing the playwriting. For every production I also sit in a corner of the rehearsal studio and busy myself making the stage props and objet art (laughs). And, in that sense, as the leader of the unit, I also get involved in the production work.

- In your plays, you have taken as your subject actual historical figures including [the authors] Edogawa Ranpo, Misuzu Kaneko, Kenji Miyazawa, [the folklorist] Tsuneichi Miyamoto and others. Why do you concentrate on actual figures?

- As I mentioned earlier, I feel attracted as a writer to figures who show a natural talent in some specific field, but as people have human faults or excesses in their everyday lives that make them failures in other aspects. But, rather than saying that I began writing biographical plays because I wanted to write about such figures, it would be more correct to say that in my search for a style of writing that suited me I finally arrived at biographical plays based specific figures.

The turning point came with Aohigeko no Shiro (2010) that was produced as a 25th anniversary production of the Seigakan company. It resulted from a commission I was given to write a new interpretation that combined Shuji Terayama’s Aohigeko no Shiro and Rio Kishida’s Akutoku no Sakae (Vice and Virtue) into one play, which turned out to be an experience in doing studies from those angura (underground theater) plays. As I worked on it I found myself greatly attracted to the quality of heat in the words used by the angura playwrights and the rich poetry of their writing.The mainstream of contemporary Japanese theater since then has been the colloquial language style of Oriza Hirata and others, but I didn’t feel that I could write that kind of play that sprung from everyday life and colloquial conversation. When I discovered the angura style of writing, however, I realized that I didn’t need to write plays in the colloquial style. It was a big realization for me. Then, as I thought about a subject matter that I could use to write in the angura style, I got the idea of using the world of Edogawa Ranpo. I knew that Ranpo had started a boarding house for students at Waseda, and I thought that his wife who ran the boarding house would be an interesting subject. And, that is how I started writing biographical plays.- That is an interesting chain of events. Would you tell us something about your play writing process?

- The first thing I think about when choosing a subject is to find someone who lived in times that might be called a “fault line between eras.” In the case of Edogawa Ranpo and Misuzu Kaneko, I choose them because they life at the time of such a “fault line” that was the year of the Great Kanto Earthquake, 1923. With that great earthquake, the old Imperial Capital of Tokyo was reduced to rubble and the ensuing rebuilding of the city ushered in a new era, and this transition affected everyone greatly. In the case of Chi wo Watraru Fune , the “fault line is World War II. As a writer, I want to look at those “fault lines between eras” and see what kinds of things are hidden there that I can get glimpses of.

I also focus on the people who lived in such times, but the more famous they are the more information there is to be found everywhere in society that paints a clear outline of the person. It might appear at first as if there is plenty of information to base your writing on, but in fact, most of that well-known information is useless material for me as a writer.- There is no meaning in exploring well-known facts.

- Yes, and it doesn’t provide any motivation for writing. I believe that the true appeal of biographical plays is being able, after initially digesting all that vast volume of information, to then grasp aspects within it that hadn’t been noticed before. Rather than the “portrait” of the specific figure that other people have already written about, I want to go in person to the places where that figure lived, to experience there with my own body and senses the sensations that the figure I will write about probably felt, and by taking the initiative myself in that way, I search out the portrait of the figure that I want to portray. After I have worked my way through all that is already visible and all that appears as non-fiction, I then begin to discover many of the reasons that I was attracted to the figure in the first place. The feeling is as if I am using my own antennas to exchanges words with that figure, that person.

The most important thing I focus on is probably to write about that person’s will and strength to live. What was the reason that the person was willing to stake his or her life on the things they did, where was the focus of their will to live? I always feel that if I can’t grasp that I won’t be able to write anything meaningful. I feel that is what I want to write about most of all.- Once you grasp those points, do the characters then begin to act and speak on their own?

- Yes. Once the characters begin to act of their own initiative and I am able to plug into their wavelength, actual quotes from the characters’ records almost become unnecessary, and their words flow from my pen naturally. That is why it is important for me to go to the places where a figure lived or worked and listen to the stories of people there in order to grasp what type of will the figure I am writing about had, the person’s roots and what the places were that the figure staked his or her life on.

- So you are not the type of writer that works in the study but one who goes out and actively searches for material in the field, aren’t you?

- For Ao no Hate about Kenji Miyazawa, I made it a play that reflected my personal experiences from my journey of research to Sakhalin (Russia). In the case of Chi wo Wataru Fune , I had a hard time grasping what it was about folklore studies that won the heart of the main character, Tsuneichi Miyamoto. So, I went to the places like his hometown of Suo Oshima and other places where he did research, like the Island of Okikamuro. I met as many people who knew him as I could and talked with them. I found that those people who were influenced by Tsuneichi still work today to find ways to carry on their lives and livelihoods on those islands through methods such as citizen seminars and Youth Council activities that will contribute to the local society. After I saw that the spirit of Tsuneichi was still alive in those people today, I found the expression “the archipelago glows.” It is an phrase that expresses the way Tsuneichi’s activities opened the eyes of the people he met and started a fire their souls that spread from place to place throughout the region. Once I found that expression, I was able to write the play.

- Your plays always have impressive scenery, like the wide-open fields of white as day breaks in Sakhalin for Ao no Hate and the view from the small shack facing the sea of Suo Oshima with the sound of the waves in the distance in Chi wo Wataru Fune .

- As I write, I realize that the desire to depict scenery is one of the big reasons I want to write plays. That scenery is the subjective scenery seen through the eyes and the heart of the main character, the scenery that remains in the character’s heart. The scenery becomes something that I rely on when I write and it also gives me motivation as I write. It would even be safe to say that I write the more than two-hour journey [of the play] in order to arrive at that scenery.

I personally have such a scene that is one of my original landscapes. I believe it doesn’t come from my own experience but is a scene based on the memories that my mother told me about. In this scene, there is a beautiful moon in the sky, but in nearly complete darkness a single figure is walking on a footpath between the rice fields. The figure is my grandfather and the landscape includes subjective emotions such as my grandfather’s feeling for his hometown and my mother’s fear in her weakness. I believe that what I am striving for is that kind of scenery.- In order to express that kind of scenery on the stage, do you talk in great depth with your stage art designer and your directors?

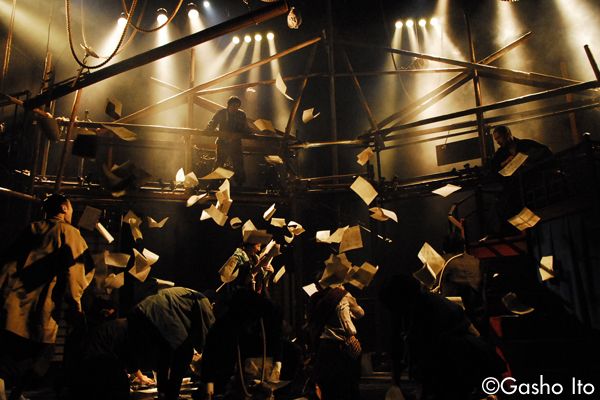

- My stage artist, Sugiyama-san, has been working with me since the start of Tegami-za, and we talk in depth about each work’s concept so we can share the same understanding of it. Each time we exchange opinion in great detail. The reason for the bamboo grove-like set used in Chi wo Wataru Fune is that bamboo as a plant is a symbol of strong vitality and in times of need bamboo serves as an emergency food for the farmers. It is also a tool for connecting to traditional Japanese culture since ancient times. Working from key words like this, we seek to make sets that include empty spaces that can be filled in with associations and memories of the viewer’s mind. In my directors I am always hoping for someone who will dissect the play and take it to new dimensions with new possibilities, so it is very exciting for me when I work with a director who feels, “I want to create new scenery!,” and I think that type of relationship works well. So, with Senda-san, we talk on and on in detail, right down to the limit and I feel that he succeeds in showing me scenery that I never would have expected.

- Because your plays are about actual figures from history, one would think that you staging of them would be steeped in realism, but hear you speak today, I clearly understand now that what you are aiming for is just the opposite.

- I feel that the plays I write seek a level of heat or intensity in the script that can’t be reached through realism, so in the directing and in the acting it also demands things that go a step beyond the normal in order to be successful. Senda-san takes that as a given quantity as he dissects the play and then goes on to bring us the type of direction that brings the actors into the present and shows them as naked, real people. That is why I can entrust my plays to him with confidence. In the end, both myself and Senda-san are very demanding people (laughs).

Chi wo Wataru Fune – 1945 Attic Museum to Kijutsusha-tachi

The subject is the banker and folklorist, Keizo Shibusawa, who used his own finances to create a museum of Japanese folklore named the Attic Museum and Shibusawa’s colleague, the folklorist Tsuneichi Miyamoto known for his extensive fieldwork. The historical setting is the troubled years of strife and war between 1935 and 1945 that saw Japan go from the ambitious establishment of its puppet state in Manchuria to the imminent defeat at the end of World War II and the folklorists who sought to record the memories of the common folk.

Nov. 20 – 24, 2013 at Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre – Theatre West

Photos: Gasho Ito

See alsp “Play of the Month”

Ranpo no Koibumi

(Ranpo’s Love Letter)

The subject of the play is the mystery novelist Taro Hirai, known by his writer name Edogawa Ranpo and his wife Ryuko who supported him by running a boarding house. In January of 1934, Ranpo has disappeared at a time when he is struggling to continue writing his novel Akuryo (Evil Spirit). In search of her husband, Ryuko goes to his beloved Asakusa district and has the illusion of seeing the story of her marriage to Ranpo played out by a puppeteer and his living puppets. (2010 premiere)

Jan. 26 – 29, 2012 at Theatre Tram

Photos: Gasho Ito

Aug. 1 – 4, 2013 at Za-Koenji Public Theatre 1

Photos: Gasho Ito

Jul. 5 – 7, 2013 at Kyoto Art Center – Free Space

Photo: Toshihiro ShimizuSora no Harmonica – Watashi ga Misuzu datta koro no koto

The subject is the poet and songwriter Misuzu Kaneko (real name Teru Kaneko) and the relationship with her husband. Teru has had to move to a small home on a backstreet and is forced to give up writing under her name Misuzu. But, she finds that even in a puddle at her feet there is a poem and decides to write a final poem with all her soul and choose death in order to protect her beloved daughter.

(2011 premiere)

Ao no Hate – Ginkatetsudo Zensokyoku (Distant Blue – Prelude to Ginkatetsudo )

The subject of the play is a trip to Sakhalin that Kenji Miyazawa made in 1923 after the death of his younger sister Toshi. The play overlaps Kenji’s journey of rumination about the real figures of his father, Toshi and his friend Kanai Hosaka and a journey of two women following the footsteps of Kenji’s journey much later. After the journey, Kenji begins his career again by beginning to write the never-ending story of Gingatetsudo no Yoru .

Nov. 30 – Dec. 3, 2012 at Kichijoji Theatre

Photos: Gasho ItoRelated Tags

Ikue Osada

Portraying the strength of people struggling to live on the brink

Ikue Osada

Born in Tokyo, 1977. Osada graduated from the School of Humanities and Social Sciences of Waseda University with a major in Literary Arts. From 1996, she began writing stage scripts and song lyrics for musicals, and from 2007, she began taking seminars in play writing given by the Japan Playwrights Association. The next year, she became a student of Hisashi Inoue, associated with the same seminar series. In 2009, she started the theater group Tegamiza as its playwright, and that year the group staged their first performances and on commission from other producers. Her works have won high acclaim writing skills defined by finely chosen words that express the subtleties of the heart and skillfully crafted storylines with great scale. In 2015, Osada’s Tegamiza production Chi wo Wataru Fune – (A Boat Crosshing the Land – 1945 / Attic Museum and the Documenters (restaged with direction by Takuya Senda) won the New Artist Award of the 70th Agency for Cultural Affairs’ Arts Awards in the Drama division, and in 2016 her Gurupuru Baru production of Osada’s play Mikan and Yutsu – Ibaraki Noriko Ibun (direction by Makino Nozomi) won the 19th Tsuruya Nanboku Drama Award. In 2018, Osada won the Individual Award of the Kinokuniya Drama Awards for the Seinenza production of her play Sajin no Nike (direction by Keiko Miyata), the Tegamiza production of Umigoe no Hanatachi (direction by Kino Hana) and the Parco Produce production of The Sea of Fertility (direction by Max Webster).

In recent years, Osada has expander her activities writing works for the New Buyo theater SOU (direction by Fujima Rankoh), for the second Ichikawa Ebizo personal production “ABKAI 2014”, for the Bungakuza Atelier Kai production Fuyu no Rakuen (direction by Hitoshi Uyama) and Yosokyoku-shu (direction by Eriko Ogawa), the Hyogo Prefectural Piccollo Gekidan production of Toyo Gokuraku Kishitsu (direction by Satoshi Uemura), the Gekidan Mingei production SOETSU – Kara Kuni no Shiroki Taiyo (direction by Ikumi Tanno), Hyakuki Opera Rashomon (direction by Inbal Pinto and Avshalom Pollak) among others.

Tegamiza website:

http://tegamiza.net/

Osada’s works, articulated in words she has discovered through voluminous research and visits to the sites of her subjects’ lives, overflow with the passion and will to live of people who lived on the brink in times of struggle and change. This interview we speak with Osada, who received personal instruction from the late Hisashi Inoue as a seminar student, and hear about the inspirations behind her biographical plays and her career experiences until now.

Interviewer: Kumiko Ohori