- After winning both “The French Embassy Prize for Young Choreographers” of the Yokohama Dance Collection EX and the “Next Generation Choreographer Award” of the Toyota Choreography Awards in 2012, you presented your first new work in Japan, Amigrecta, in Sainokuni Saitama Arts Theater’s “dance today” series. It is a series that provides young choreographers with the chance to create works with generous support including a month and a half of time for studio work and rehearsals. It was also a chance to perform a work in a much larger theater space than you had used until now, but you and Iwabuchi-san created a work for five dancers with unique movement that produced a very full and intense stage. What was the working theme behind this work?

- With recent events like the near melt-down of the Fukushima nuclear reactors and the devastating radioactive contamination it caused over a large area, the thing I had in mind all the time I was working on this piece was the living things that are in danger of being lost. In Japanese, the character for the “beloved” can also be read as “sad.” When we think of loved ones, it can sometimes bring us to tears. Where do these sentiments come from? The feeling of continuing loss and wish to see living things continue their chain of life, that is the dimension of the “life and death” question that I wanted to explore as much as I could in this work.

It seemed that different people perceived the repetitions of the dancers’ movements differently, with some feeling that it suggested past time that can never be recovered, while in contrast others felt it symbolized the possibility of repeated encounters with the things we have known. Especially, because it was such a large theater, I felt that I saw some new visual possibilities that are different from the kind of observation of the body at close quarters that I have been used to working with. - Initially, you had studied ballet, hadn’t you?

- I began taking ballet lessons from the age of five in the town of Kawagoe where I grew up, but I don’t think I was a very good student (laughs). I didn’t care much about the ballet contests like other dancers. I just liked dancing and I had this vague idea that I would just like to continue dancing for the fun of it. If there were times when I might be bullied at school, I could forget it all when I got to my ballet class because it was such fun for me.

I don’t think I had a definite dislike of being one of a group that all moved and performed as one, but I guess I never really took to it by nature. I couldn’t stand it when I felt something was unfair and I often had fights with my teacher as a result. When I was in high school I began to think that if I was going to do ballet it would need to have some acting ability, so I joined the school’s drama club. But, often I didn’t go to classes. I commuted to school by bicycle and often I would stop at a park along the way and spend my time drawing pictures or reading a book. The only thing I really did with interest was my after-school club activities. I was rather emotionally unstable in my high school days, though, and I ended up quitting even those club activities.

The first time I saw a contemporary dance performance in my senior year of high school when I happened to see an article about Maguy Marin coming to Japan to perform (in 1997), so I went to the Setagaya Public Theatre to see the performance. The piece I saw was waterzooï and it was a real shock for me to see a kind of dance I had never imagined. I remember coming away really excited by the experience. - Maguy Marin is one of the leaders of France’s contemporary dance world. That must have been a good encounter for you.

- It wasn’t as if that encounter was what made me decide to go into contemporary dance, but after graduating from high school I had the feeling that I wanted to do some other types of dance besides just ballet. I looked for a studio in the Tokyo area that taught modern dance as well as ballet and began going to lessons at the Dance Works studio taught by Kimio Nosaka and Nobuko Sakamoto. But, I also had an interest in theater and musicals, so I was going to auditions in those fields sometimes too.

After doing that kind of thing for about two years I had the opportunity to perform in a work of Kenshi Nohmi through the Saitama block of the Japan Ballet Association. Shortly after that performance, I auditioned for Un Yamada’s work Haikaburi based on the Cinderella story (2003) and got a part. Those opportunities began to change my situation considerably. - What was it like to be involved for the first time in contemporary dance creation?

- Until then I had only been doing ballet with girls older than me, so I just loved everything about this new experience of doing dance with others mostly the same age as me from 10:00 in the morning until 10:00 at night. The dance that Un [Yamada]-san created was also something fresh and inspiring for me. While it’s still the same today, it took me time to learn new things and I probably didn’t know how to get a real understanding of a piece, so I was just working as hard as I could to keep pace.

After that, I was able to dance again in her next work, One♦Piece, and I feel that I learned from Un-san the importance of thinking out thoroughly the way you perceive your body. And, what I learned in that regard stays with me today. It has also been very important for me the things I learned about preparing oneself prior to any performance as a dancer, such as how to live as a responsible member of society and what state of mind you approach the stage with. I was also scolded a lot (laughs), but now that is helping me today when I am creating works with younger dancers. - The kinds of things you have just spoken about may be the reason that so many good dancers come out of Un Yamada’s dance company. In the year 2003 when you performed in Un-san’s works, you also created your own first composition, the solo piece Shoujo Jigoku (A Young Girl’s Hell).

- I met Minako Kimura at Un-san’s studio and later I was told that the two of us had a very similar air to us, and that led to talk about us doing a duo piece together. But, then I got the feeling that no matter what I would be doing as a dancer from then on, I would have to have the strength to dance solo, so I decided to create a solo piece first. That resulted in the piece Shoujo Jigoku that I performed at the Session House in Tokyo.

- Was it based on Kyusaku Yumeno’s short story by the same title?

- Yes. I was attracted to the woman in the story who draws the people around her into her world with her compulsive lying. In that piece I dance in a nurse’s costume to the music of PIZZICATO FIVE’s piece “Porno 3003” with the voice of actress Mari Natsuki. At that time I would choose the music first and then choreograph a work based on the image I got from the music. That piece was fairly well received and it helped me rediscover the pleasure of creating things. I didn’t need to raise my legs high or do beautiful turns, I could make pieces with the kind of slightly off movement that I did when I danced in my elementary school years. With that piece I felt that I had grasped the joy of expressing my own world, even if it was a bit clumsy. After that, I created a duo piece titled Haruko no Musume (Haruko’s Daughter) with Kimura-san, who is the same age as me. It was a piece that mixed together elements of Jigoku Shoujo and a solo work by Kimura-san.

- It is the work where you covered the floor with kimono fabric to dance on, isn’t it?

- The piece that I used fabric for was the one that I performed in 2004 at the “Dance ga Mitai” event at the Kagurazaka die pratze theater, and I heard later that you [this interviewer, dance critic Takao Norikoshi] saw it and recommended me for the Toyota Choreography Award. Unfortunately I didn’t get past the preliminaries. One time when I went with Kimura –san to hear an appraisal of it, I remember very well being told by you not to worry about what people think and just keep doing what we want to do (laughs).

- After that you participated in works by Kakuya Ohashi.

- In Ohashi-san’s work Anata ga Koko ni Ite Hoshii (Wish You Were Here) (2004) there is a scene where the dancer MiuMiu eats a rice ball on the stage and then vomits, and I thought, “I wanted to do something like that!” So, I auditioned for Sacrifice (2005). At that time, Ohashi-san’s working method was to do things such as show the dancers videos or photographs of something like hieroglyphics and tell them to make movement from what they saw, and create pieces with everyone contributing. Then he would pick and choose from the things that came out, saying, “We’ll use this,” or, “We’ll cut this part,” and put it together. I couldn’t believe anyone created works that way.

- The next work you created was another solo piece titled Atamania (2006).

- Yes. At that time I had become a bit unstable mentally, and when I tried to think it was as if there were a fog in my mind and a sensation like rustling, so I made that state the subject of a piece. It was a time when I was obsessed with the idea that my body and my very existence was something dirty and I wanted to mince myself into pieces in a mixer. But, since I couldn’t do that I put watermelon shaped as figures into the mixer and then drank the soup that came out. The idea I had in mind was that if it went through my dirtied body everything would become dirty, and finally it would come out as a flush of completely black water. Looking back now, it seems like all too simple a concept. I made the mechanism for the flush of black water myself and practiced flushing the black water from a tank on my back in my home’s bathtub. When it was well adjusted I showed my father what it looked like in action. He was appalled (laughs).

- In 2008 you formed the group “Mure” with other young dance artists of your generation (Teita Iwabuchi, Naoko Ogata, Kaori Seki, Nei Hasegawa, Yu Harada, Azusa Matsumoto, MiuMiu). How did that come about?

- Although as dancers we often talked together in a friendly way and went to see in each other’s works, but it usually ended with only that. Even if we performed in the same works, to a surprising degree we didn’t really know deeper things about each other, such as what we thought about when we went on stage. When I was having an in-depth conversation with Teita-san about the fact that things didn’t develop beyond that, he lent me a book by the artist Genpei Akasegawa and learned about how groups like [Akasegawa’s] High Red Center and Rojokansatsu Gakkai worked together with artists of their own generation.

So then I spoke to everyone about creating a group where those of us that had the same interests could exchange ideas and think together, without the prerequisite that we were going to necessarily work toward performances together. The original purpose was to get to know each other, but we quickly reached the consensus that it would be best if we did do performances. From there, we were soon doing a succession of performances, beginning with Mure’s jointly choreographed work Atarashii Sekai (New World) in 2008, the works we choreographed for each other presented as 6 : 0 / Sakuhinshu (6 : 0 / Group of Works) in 2009 and Shizukanahi (A Quiet Day) performed in a ruined building in 2010. Presently, everyone in the group is busy with their own work and our work together is on hold for a while, but I hope we will be able to continue doing things together in the future. - I have heard that you attended a Gaga (the physical movement method developed by the founder of the Batsheva Dance Company, Ohad Naharin) workshop in Israel.

- Working on Atamania and the Mure group works had me somewhat overheated. So, when I heard that the Gaga Japan group was gathering Japanese dancers to go to Israel for a Gaga Intensive course, and since I liked the works of Ohad Naharin, I decided to go along.

- What was it like for you being on a workshop tour in an unfamiliar foreign environment?

- I wasn’t in a very good mental state when I went, but it was good doing the Gaga technique everyday in Tel Aviv and then soothing my tired body in the sea. And it was also good to get to know Kikue Takagi of the dots company in Kyoto and find a lot in common and talk together about working in groups. The whole experience gave me back a lot of strength.

The workshop made me realize that I had been creating works without knowing any training methods or physical movement methods other than the ballet I had studied. With Shoujo Jigoku and Atamania I had been struggling to create without knowing how to give form to my inner desires. But, as I learned to move using an image with the Gaga method I got a very clear image of how to view my body. Then I came back to Japan having found a method that suited me and feeling healthy, and that is when I created the solo piece Yuki-chan (2008). - With Yuki-chan you won the Labo Award of the ST Spot venue where you performed it. I was there at the time and saw you perform, and I must say that it was a work that surprised me. As I watched your slow, insect-like movement, at one point I realized that your body had begun to shine as if covered with a wet substance.

- I wanted to get an effect like the sticky, wet trail a slug leaves when it crawls, so I attached four condoms filled with lotion to my costume in different places in a way that I would gradually get wetted by the lotion. Yuki-chan is the name of an insect and the situation I had in mind was that of a man watching the insect in an insect cage. To get a look like a cockroach, I greased my hair completely so it wouldn’t move and made it cover my head right down to my eyes. (Laughs)

- Why did you choose to dance as an insect?

- In the process of practicing the Gaga method, I realized that I was the type for whom it is easier to explore the sensitivities and perceptions of the body rather than exploring and expressing emotions. I realized that I am not one who can create in a way that says, “This is the person’s emotional state, so this is the way the person moves.” So, I chose to move as an insect rather than a human being. With the tactile organs of an insect and its slimy-ness …. Of course, at the same time I am a human, and a girl. That work was a turning point leading to what my dance is today. But, at that time and still today, I never set “slow motion” as one of the basic elements of my movement. Am I just slow [by nature]? (Laughs)

- Maybe the adjective “slow” comes to mind because there is a different flow of time in your works than the usual human sense of time. However, the slow movement serves to emphasize a variety of things happening within the body. To be precise, I get the feeling I am watching time itself.

- Since I set various contexts for dancers, there are indeed a variety of things happening. Stretching out the time framework creates reasons for movement, and I think it can be sensed that moving too quickly can cause the flow to be lost. How to communicate this to the audience is an issue I am still dealing with, but to me Yuki-chan was an important work in terms of grasping my style as one that might better be described as moving “with deliberate care” rather than moving “slowly.”

- In 2010, you presented the group dance Marmont that used fragrance.

- Dance performances can now be recorded in beautiful quality. So I thought about the question of what there is that can only be seen or experienced there in the performance venue? I decided that I wanted to do something that only the people who came to the theater for our performance could experience, something that the people in the audience could all experience together with their own senses and would make it a special experience. And another thing I thought was, even though every type of living thing has its own smell, aren’t we living in a way that negates that aspect? When I began looking for someone who could advise me about fragrance, I met Toshifumi Yoshitake of the Perfume Design Laboratory, and he was kind enough to cooperate with me throughout. The fragrance as dispensed from a device made of absorbent cotton wool hung above the stage that was saturated with the essence and a fan to disperse it.

- Since then you have used fragrance in a number of works. How do you choose the fragrance?

- With Marmont I wanted a fragrance that expressed the world, a fragrance that had the smell of living things and our smell, a fragrance that connected to nostalgia, and that is the image I communicated to Yoshitake-san. Then he created samples for me and we worked together on the balance to get the right fragrance. With the group work Hevellud (2012), Yoshitake-san suggested to me there were fragrances that effect people’s senses in ways such as creating the feeling that there is something stuck deep in the throat and that is what we used. Of course fragrances spread out and dissipate, so I don’t know how much effect it actually has. Lately my requests have gotten rather excessive, and with my latest work Amigrecta I was asking for a fragrance will be associated with death, a smell as if a person were burned, the smell of the inside of the body, the smell of blood, etc. (laughs), and the give-and-take is very interesting every time. Eventually, with Amigrecta we used the fragrance of myrrh that was used for making mummies and a fragrance that suggests mother’s milk. When I was in France I had some of the students at CNDC try several fragrances I took along. For example, a fragrance that was designed with the image of a temple’s smell to evoke nostalgia for Japanese and it was interesting that for them it had the image of church. It made me think that even if we are not conscious of the fact our responses to fragrance have deeply rooted cultural associations. But, fragrance also has a violent aspect in that the mere act of breathing draws it in whether you want it to or not, so you have to be careful how you use it.

- Besides the sense of smell, the sense of touch also plays an important part in your works, as it did in Marmont. Still, it is rarely connected to emotional effects such as the desire to touch someone because you like them or the joy of holding someone. The kind of contact you show in which the purpose seems to be only the act of verifying the other’s presence is something I find to be very interesting.

- It is also a fact that the process of having deep contact with people is something that I haven’t been able to do well until now in my life as well, and perhaps that is something I seek. As you have just said, rather than the emotions resulting from touching, I constantly have the desire to be able to reach more deeply into the other person, and little by little I seem to be coming to the realization that this desire is revealing itself in the feel of my works (laughs).

- But, the skin is at the same time an organ for feeling the other person and a barrier through which nothing can pass any deeper. And that in itself is a reality of “existence.”

- Yes, it is. In Marmont, there is a sequence where one dancer is lying on the floor with the feet in the air and another dancer is going through movements like flipping over on top of those feet. In this case it is based on an image that although the two are touching they don’t really “exist” in each other’s consciousness. You could explain it as using the difference in elevation of the two dancers [one at floor level and one held up in the air] as a means to express the co-existence of a person that is here and one that isn’t.

Also, it is often the case that the touching [contact] is not done hand to hand but using other parts of the body. Since we normally use our hands unconsciously too much, so I don’t use hand to hand contact but consciously change the point of contact, as if to ask, for example, when arms contact each other, from what point does it become the arm [as opposed to the hand]. While working on Marmont I did quite a lot of research for reference purposes about the tactile organs that living things other than humans have. In the end, the closest explanation of my image of what a dancers is may be a creature that has an infinite number of tactile organs covering the entire body (laughs). - In 2012, you won two of Japan’s most important choreography awards one after the other: “The French Embassy Prize for Young Choreographers” of the Yokohama Dance Collection EX2012 for the piece Hetero co-created with your professional and private partner, Teita Iwabuchi, and the “Next Generation Choreographer Award,” grand prix of the Toyota Choreography Awards for your work Marmont.

- Hetero is a work that Iwabuchi and I created gradually through an exchange of ideas. When co-creating with Iwabuchi, for some inexplicable reason I am able to try dealing with the subject of “human beings” rather than my usual insects and such (laughs). The awards are encouraging for me, but even if they bring bigger expectations on me, I can’t change all of a sudden as a result, so I will just have to ask everyone to kindly watch me develop at my own pace as I have until now.

- As part of the French Embassy Prize for Young Choreographers, you won a period of residence in France with Iwabuchi-san. How was it?

- Due to some work commitments, we spent three months from the middle of September to the middle of December 2012 in Angers at CNDC (national choreography center), and after that two weeks in Vienna. During the residency at CNDC I choreographed a piece for two of the students there and did a performance of Hetero. With the two student dancers I did a considerable amount of detailed instruction about the use of the body, and they seemed to discover a lot from it. As for our performance of Hetero, it was well received, with people saying that the absence of any sound [or music] worked successfully to give the viewers time to let the movement stimulate their imagination. During the stay in France and Vienna, everything about the daily life was nourishing and rewarding. I was able to see a lot of dance performed and it was like a dream come true having the studio space available 24 hours a day and think about the body constantly. In the markets I was able to discover a variety of vegetables and I learned how to prepare them, and discovering these kinds new things turned out to be a form of communication in itself that I was able to absorb fully and bring back with me.

- Since your latest work Amigrecta there must be even more attention focused on you and your work. Please tell us what do you foresee for the future.

- There are things that I want to show, but there are so many things I must work out along the way. I am working on a new work based on my work Hevellud, but since I am inherently a person who has a difficult time feeling positive about myself, I get lost in a cycle of feelings of wanting to melt together into other people and wondering if I am lonely and if it is not good to base a work on loneliness alone (laughs).

- I think you have a tendency to under-evaluate your worth (laughs).

- I am often told that. It seems to me that among the dancers of my generation there are a lot of people who feel the same way as I do. But, I do have a lot of curiosity about a variety of things and I am strongly motivated to do research and experience new things. I believe that this curiosity has to some degree been a saving grace for people like me who have a difficult time feeling positive about ourselves, the people that you might call the group that didn’t commit suicide. If it wasn’t for this curiosity I might have become a stay-at-home recluse. Doing Gaga I learned how to face and consider my body and it has helped by many friends and dancers and the staff, and I have experienced various things such as marriage that have brought me to the point where I am today as an active dancer. So, this is the only way I can dance. I know that I have to take my time and move forward at my own pace, so I intend to keep struggling and facing my creative process with diligence and resolve.

Kaori Seki

Kaori Seki’s sense of wonder –

Explorations in physical perceptivity

Kaori Seki

Born in 1980, Seki began taking classic ballet lessons at the age of five, and from the age of 18 she commenced study of modern dance and contemporary dance and began creating pieces of her own at the same time. In 2008, her solo dance work Yuki-chan performed in the ST Spot Labo 20#20 series won the Labo Award. In 2012, Seki won two important awards in “The French Embassy Prize for Young Choreographers” of the Yokohama Dance Collection EX2012 for the piece Hetero co-created with Teita Iwabuchi, and the “Next Generation Choreographer Award,” grand prix of the Toyota Choreography Awards (performing the piece Marmont). In 2013, she presented the new work Amigrecta, produced by the Sainokuni Saitama Arts Theater. Also, as a dancer Seki has performed in the stage productions of works by artists such as Co. Yamada Un and Kakuya Ohashi & Dancers, and from 2007 she joined with other dance artists of her generation to launch the “Mure” artist group. She is the focus of much attention today as an artist with a unique dance language of her own and finely tuned sensitivities.

Interviewer: Takao Norikoshi, dance critic

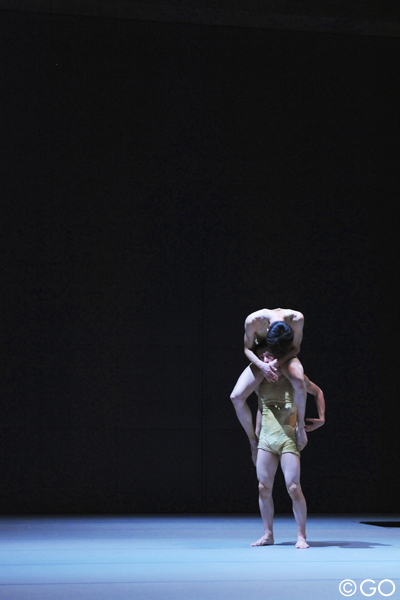

Amigrecta (2013)

Produced by Saitama Arts Foundation

Photos: GO

Haruko no Musume (2003)

Photos: Yoichi Tsukada

Yuki-chan (2008)

Photo: Kazuyuki Matsumoto

Marmont (2010)

Related Tags