A first attempt with comedy in the new Bunraku play Sorenari Shinju

- August of last year (2012) saw the premiere of the first Bunraku play written by comedy scriptwriter Koki Mitani, titled Sorenari Shinju (Much Ado About Love Suicides), and a restaging took place this summer as well. It is a comic play on the classic tragedy Sonezaki Shinju written by the master playwright Monzaemon Chikamatsu shortly after an actual incident involving the suicide of a pair of star-crossed lovers. In Mitani’s comedy version, Chikamatsu’s play Sonezaki Shinju has caused a rush of couples coming to the same woods at the Sonezaki Shrine to try to commit suicide like the original couple. The main characters in Mitani’s play are a couple who run a manju (a type of Japanese cakes) shop near the shrine who fret about the loss of business due to this suicide rush, and in the course of events even Chikamatsu himself was one of the characters. Unlike traditional Bunraku plays, I was impressed to see the audience breaking out in laughter numerous times during the performance. In what ways did you find performing Mitani’s Bunraku different from the [traditional] Bunraku you have performed until now?

- Basically, Bunraku plays are all tragedies, although there will sometimes be chariba sections where the storyline is funny. The fact that there are no comedy plays in the Bunraku repertoire was a big difference in itself.

- By chariba you mean scenes like when a character eats a poisonous mushroom that causes the character to start laughing ceaselessly and you express that in the recitation by using a variety of different types of laughs. Having a laughable scene like that can break the tension of a sad story and provide a moment of relief, while at the same time allowing the tragic nature of what follows come with more weight, can’t it?

- In Bunraku plays there are some parts in the recitation that provide that kind of comic relief, but I have never performed a play in which the entire story is a comedy, that put me at a loss at some points. Of course, since Mitani-san is a comedy writer, I naturally expected it was going to be a comedy but there were a lot of parts that I didn’t know how to express and I ended up learning a lot from Mitani-san during our rehearsals.

- Can you give us some examples of the actual advice he gave you?

-

For example, there is one scene where the husband of the manju shop sends off a couple that wants to commit suicide with the common parting expression, “

Tassha de na.

” (I wish you good health, or, Go in good health). Mitani-san told me to say that line with more of a joking tone.

Of course, by reading the script you know he is not saying it in earnest. But, I didn’t know how much of a feeling of jest or lightness to bring to it. Because, in Bunraku there is never an attempt to making a line sound overly in jest, or in too playful a tone. In most cases, the lines in Bunraku meant to be interesting when delivered in a natural tone or a serious tone. Our [Bunraku] masters tell us that there is nothing amusing if the performer tries to act funny. Bunraku is interesting when it is performed seriously. Since our art as performers is in our voice, we can’t undermine that by using strange gestures or trying to look funny. For that reason, I think it is difficult to make the audience laugh. - So, what you were asked to do in this way was quite different from your style of recitation used in the traditional Bunraku plays, wasn’t it?

- Well, what we did in our performance wasn’t really so different from our traditional Bunraku style. Perhaps the biggest difference was in the speed. Mitani-san told me that he wanted me to speak faster, at a quicker tempo. The first character to appear in the play is the daughter of a big merchant who has fallen in love with one of the store’s servants and wants to commit suicide with him because it is a love that can never be accepted of by her family, but in Bunraku, no matter how anxious a character may be the lines are never spoken quickly. Still, Mitani-san kept telling me to do it, “Faster, faster.” Mitani-san’s scripts are wordy, and if his Sorenari Shinju this time was performed at the traditional Bunraku tempo, the play would probably have lasted about four hours. Looking at the DVD of the premiere performance, I realized that the attempts to increase the tempo often resulted in insufficient time for dramatic pauses. So, rather than having the appearance of moving at a fast tempo, it often appeared unnaturally hurried. So, for this year’s performance I took measures to try to correct that.

- Traditional Bunraku plays use old expressions and wording from Osaka in the Edo Period (1603-1868) that are no longer used today, but Mitani’s script is written in contemporary colloquial language. You surely needed to make some adjustments to recite it in contemporary language, didn’t you?

-

That is an area where I had to break some of the standard rules of Bunraku. And, there was also the matter of the words that have entered Japanese after the Edo Period from foreign languages. For example, the word

patorouru

(patrol). Mitani-san told me I should pronounce it with special accentuation because the audience would find the miss-match funny.

There is no such thing as a [stage] director in Bunraku. But, for this play we had a director, who was also the playwright himself [Mitani], so this was a completely new experience for us. By the way, in the case of Bunraku tayu you can say that a performer’s everyday practice is done with an element of stage direction. Your master or the shamisen teacher will correct you or advise you in practice, saying things like, “There is no sense of distance between the characters, so speak the lines in a way that gives that sense of distance,” or “Speak with such-and-such an emotion.” That advice serves the role of stage direction in Bunraku. - Did it make things easier having a director [Mitani] in the case of this play?

- Yes, it does make things easier. Especially since it was the playwright himself and he can explain his intentions directly. With the premiere last year it was my first experience with a comedy and I was desperate because it would be disastrous if the audience didn’t laugh when they were supposed to because of the way I delivered the lines. If that happened it would mean that the tayu [myself] wasn’t bringing Mitani-san’s script to life. It was also a case where people who had never been to a Bunraku performance would be coming to see this play. But, we were able to get a good reaction from the audience, so quite honestly I was relieved by the result.

- In Bunraku, as well as other traditional Japanese performing arts, there is no tradition of holding days and days of rehearsals to develop a work for the stage. The forms of performance and recitation are handed down through the tradition, so if you have done your regular practice to learn a part it will present well on the stage, so it is only necessary for the performers to gather a few times before the opening performance and run through it to coordinate things sufficiently. Since Mitani’s Bunraku was a completely new play for all of you, how did you rehearse for it?

- For the premiere last year, we began rehearsing during the June session of regular performances at the Osaka National Bunraku Theatre. In the case of the gidayu you can’t get an image of what the play will be like just by looking at the script, and you if you don’t have the music you can’t rehearse. It was around June that the shamisen master Seisuke Tsuruzawa composed the music. I got him to prepare a recording for me to practice with between my regular Bunraku performances. Then we practiced the joruri (tayu recitation) and the shamisen parts together for about a week, and we got together with the puppeteers to rehearse three or four times and then another two days of rehearsals were held before the premiere in Tokyo.

-

Mitani is by no means a specialist in Bunraku. Was there any advice that you and the other Bunraku people gave Mitani in preparation for the staging of this play?

I believe that the music reflected the intentions of [the shamisen master Tsuruzawa] Seisuke. I have also heard that Seisuke-san also suggested the use of “

nakiwari

” (laughing through tears) type scenes in order to give the play a more Bunraku-like flavor.

The puppeteers also held a number of discussions with Mitani-san. The puppeteers refused several of the requests for unconventional movement by the puppets because it would no longer be Bunraku, and I hear that Ichisuke Yoshida made the famous statement that for a Bunraku puppeteer the puppet was not simply a tool. (Laughs) There were also requests for the use of puppets not used in Bunraku and unconventional requests like wetting the puppets with water, but the puppeteers wanted to use the puppets they normally used in Bunraku performances and to make this new play one that could be performed in regular Bunraku performances. I believe their feeling was that they were not interested in simply doing something different but doing things that would be interesting within the framework of Bunraku.

But the idea of having a water scene in which the puppets would “swim” across the Yodogawa river was something that would never be imaginable to Bunraku people. Ideas like this are what make Mitani-san exceptional. When he asked at one rehearsal if it would be possible to do a water scene, the response was, “Let’s try it.” When Mitani saw the puppeteers’ attempts, he apparently said, “Yes, that’s it. Let’s do it like that.”- Does performing new works like this contribute anything to the way you perform plays of the traditional Bunraku repertoire?

- Since we in the Bunraku world tend to take a conservative view of our traditions, I believe the performance of new works that provide new viewpoints from which to look at Bunraku is a very good thing. However, if asked whether I learn anything new from them in terms of performing technique, I would say no. But, there are things that we have learned in our traditional training that can be applied to new works.

- For the August Bunraku performances in Osaka you performed Urikohime to Amanjaku . This is a “new” play first performed in 1955, half a century ago, and it was written by Junji Kinoshita in colloquial Japanese based on a folk tale. Was anything gained from the Mitani Bunraku play applied to this performance?

-

In the case of

Urikohime

we have a wonderful model in the [recorded] performance of the great Master Koshijitayu Takemoto, so as with plays in the traditional repertoire I had the example of his intonations to follow as a precedent when I performed this play. In Bunraku it is not considered a very good thing to add your own personal modifications to the existing forms. Because, the superficial changes that we might add are completely different from the precedents that the great masters of the past created after much thought and practice. As we follow the forms that have been handed down from the past the individuality of each performer will naturally come out. So, I believe that the essence of traditional theater is the accumulation of the individual performers’ extra nuances that have come out naturally in the course of their careers and then reflected in the performances of the generations that follow.

The path of the tayu beginning from the age of 13

- How many years have you been active as a performing Bunraku artist? You are a native of Tokyo, and since there are only four months of Bunraku performances in Tokyo each year, there must not have been many opportunities for you to see actual performances. Were your parents Bunraku fans?

- I began when I was 13, so it has already been more than 30 years now. My parents were the first to take me to see Bunraku so that I could see that this kind of puppet theater existed. My grandparents were Kabuki fans, so that was a factor. But, my parents didn’t have any special interest in Bunraku.

- What was your first encounter with Bunraku?

- I first came to like puppet theater from watching the Shin-Hakkenden puppet theater series broadcast by the NHK national television network. But, I don’t think it was only me, I think all of us children liked it at the time.

- The puppets used in that series made by the puppet creator Juzaburo Tsujimura were very appealing, because unlike the usual cute puppets used in children’s puppet theater, his puppets had expressions that reflected the natures of their characters in the play. Also, the story was based on the Nanso Satomi Hakkenden of the Edo Period playwright Bakin Kyokutei and it took the form of an action play that many adults also became absorbed in.

- I don’t know what my parents thought about it, but as a way of cultivating my interests in an educational form, they told me about Bunraku as another kind of puppet theater and took me to see a performance. As a result I became hooked on it. I didn’t know the contents of the stories, but I quickly found the puppets themselves to be amazing. I always liked music too, and I thought the sanbaso introductory music was good. So, after leaving the theater I asked my parents to take me to a record store and they happened to have a sanbaso record. That was a unfortunate coincidence that changed my life (laughs). Listening to that record at home made me want to learn to play the shamisen.

- Even if you liked puppet theater, you must have been a somewhat unusual child to want to become a Bunraku performer, don’t you think?

-

When my grandmother heard that I wanted to try it, she apparently told a friend of hers who worked at the National Theatre that her grandson liked Bunraku. That person then got us an introduction to someone working in the program to train next-generation Bunraku performers. Then, that person said he would introduce us to the Bunraku performers, and when he took us backstage the master Rotayu Toyotake happened to be there and I was introduced to him.

It was just at that time that my father was transferred to work in Toyama Prefecture and the person from the training program told us that if I was interested in becoming a tayu it would be good to begin by studying Jiuta (A form of shamisen music that emerged in the region around Osaka in the Edo Period), and they gave us an introduction to a Jiuta teacher in Toyama. In the roughly two years my family and I were in Toyama, I took lessons in Jiuta and shamisen. The other students were all women, and I was the only boy and elementary school student. So, I was naturally the center of a lot of flattering attention, and I came to like it (laughs).

When we eventually returned to Tokyo, we went to see Master Rotayu and he said that if I still wanted to do Bunraku the shamisen Master Juzo Tsuruzawa lived in Tokyo, and we were then given an introduction to him. Master Juzo was already about 80 years old at the time and was about to retire. Apparently he was saying that he wouldn’t take any more students because of that, but I was fortunate that he did decide to take me on as a student.

So, after that I went to have Master Rotayu teach me shamisen and the gidayu recitation at his studio in the Yotsuya district of Tokyo after school in the afternoon. Unlike today’s method where students try to learn by listening to tapes, the Master taught me by the old method, in which he would play or recite a part first and then I would play or recite along with him the second time, and then the third time I would do it alone. At first it was just a matter of imitating the Master. As a child you don’t think about anything else, but just do things as the teacher tells you. That is why it is important to start learning when you are a child, I believe. - Does that make you one of the last generation to study by the old method?

- I guess it does. Master Juzo [Tsuruzawa] taught me about ten plays. And it was done a little at a time. And he had me go through whole plays like Sodehagi Saimon and Ehon Taikoki that are hard for children. Looking back, I imagine that rather than teaching me so that I would memorize the plays, by the way he had me practice he was teaching me what the gidayu (recitation of the play) is and how it is structured.

- What is this structure you refer to?

-

There are a number of means of expression, but there is a “common sense” or a common pattern to it all. For example, if one phrase or word is spoken slowly, then the next one is delivered quickly. If the phrase is

nokoru tsubomi

(remaining buds), when the

nokoru

is pronounced slowly, the

tsubomi

will be pronounced quickly, and conversely, if the

nokoru

is pronounced quickly, the

tsubomi

will be pronounced slowly. Since there are a variety of different forms, no single form can be said to be the correct one, but you will never have a case where both are pronounced quickly or slowly in progression. Also, depending on the situation, the tone of the voice will change too. I was taught basic rules that apply to every play, such as the rule that if the character (puppet) is standing the words will be spoken in a higher tone, and if it is sitting, the head will be down and so the lines will be spoken in a lower tone.

Because I was a child I didn’t understand the meaning of a lot of the things I was being taught, but the things I was told at the time have stated clear in my memory all these years. I am truly grateful that I was able to receive those valuable lessons, that training, from the Master in that way. Now I am teaching in the training program for young aspiring Bunraku performers at the National Theatre, so I have learned how extremely difficult it is to teach complete beginners. In the case of younger apprentices who have already learned the basics, I can simply say, “No, this and that parts are wrong,” but with the novices entering the training program who don’t now anything about Bunraku (gidayu) recitation, I have to show them by giving them examples, and if I feel that they haven’t understood, then I have to think of means that will help them understand. So, I am truly grateful that Master Juzo in his old age made the effort to teach a young middle school student like me who didn’t know anything. - After studying both shamisen and tayu recitation, there came a time when you had to chose which one you would specialize in.

- I didn’t know which one I was better suited for, so I took lessons in both shamisen and tayu recitation. But, when it came time to choose one, I guess I felt that being a tayu would be better—since I had no idea how difficult it would actually be. Later I found out from his wife that Master Juzo was disappointed when he heard that I had chosen to be a tayu. It appears that my Master wanted to make me a shamisen player.

- To become a tayu, you chose to apprentice yourself under Nambutayu Taketomo.

-

For gidayu, my voice is not a big voice. I am not the type that chooses plays where you can belt out the recitation in a big voice with impressive volume. So I got advice from people around me that it would be best to choose a master with voice quality similar to my own.

In addition to the opportunity to see his approach to the art of Bunraku, one of the great benefits of studying under Master Nambutayu was getting to know his wife. Because she was from the old entertainment [red-light] district of Osaka, she had a different demeanor from other people. When she laughed, she automatically made it poised and delicate “oh ho ho” for example. Her way of speaking and her gestures and movements were a bit different from regular people. There are many Bunraku plays that are set in the red-light district. Sonezaki Shinju and Shinju Tennoamijima are two examples of plays where the heroines are courtesans of the red-light district. For us today, that lost world is like a fantasy world of the past, but Master Nambu’s wife would tell us stories about things she saw, like the actual formal robes of Yugiri, the heroine of the Bunraku play Kuruwa Bunsho . Things like that bring that lost world much closer to reality for us. Knowing that these people actually existed and something about their lives makes it possible for us to create mental images of them [for our performances]. - Nambutayu passed away not long after you began studying under him, and then you became the apprentice of Rotayu. Unfortunately, the master Rotayu died while still in his fifties, after which Shimatayu Toyotake became your fourth master, wasn’t it?

-

Having been taught by a number of masters gave me insights into a number of different ways of looking at things. And, in some cases a new teacher would completely negate something that I thought I was doing well. But, in the process of practicing under them I came to see that in some cases the form of expression is different but the essence is the same, and in other cases they were completely different. Anyway, I learned a lot from the experience.

The appeal of the gidayu

- By the way, may I ask how many stages you perform a year?

- With the regular Bunraku performances alone it is just over 130 days a year, and when there are no performances I am practicing, so there are only about a dozen days out of the year when I am not doing gidayu recitation.

- That means you are completely immersed in gidayu throughout the year.

- I believe that you have to be completely immersed in the gidayu if you are going to do Bunraku. Master Juzo was born and raised in the Meiji Period (1868-1911) and he told me when I was a child, “In the old days there were no cafes, no movies and of course no television, so the only thing you could become absorbed in was your art.” For that reason there was a depth to their art that is different [from people’s today]. It may sound a bit extreme to say this, but I believe that our entire life has to be based around Bunraku, day in and day out. Not only when you have the gidayu text open in front of you, not only when you are being taught by your teacher, not only when you are performing on stage—you have to have the art in the back of your mind at all times. If you aren’t thinking about your art with that kind of depth, you will never be able to attain an art on the level of the masters.

- In the gidayu recitation, a single tayu recites narrative that tells the storyline as well as reciting all of the spoken lines of the [puppet] characters with very little change in the voice quality, for both female and male roles and for roles of the elderly characters and child characters. The tayu even does sound effects with his voice. What is more, when there is a change of acts or an intermission, the tayu can be changed and suddenly the same female character whose lines you were reciting will now be recited by a different tayu in perhaps a much huskier voice. Bunraku audiences accept this a natural and find nothing strange about it, but for people who are not used to seeing Bunraku this might appear very unnatural.

-

When there is a change of the tayu [in the middle of a play], the impression of the voice will probably be different, but after you listen to it for a while that difference is forgotten and there is no longer anything unnatural. This is one of the unique aspects of Bunraku. There is nothing that says that the voice has to be sweet and beautiful if the role is that of a young woman, and if the tayu is skillful even a thick or hoarse voice can be made to sound attractive or cute in a young female role. The art is in making the lines sound attractive or cute regardless of whether it is a beautiful or a coarse voice. Then the audience is drawn into the story and they forget the difference in the quality of the voices when the tayu is changed.

The masters tell us that for the delivery of a character’s lines we must first get an image in our mind of the type of person the character is. Probably the most difficult thing for people today to understand is the differences in social class [of people of the Edo Period]. Even if they are both young woman of the same age, a common girl of the town will be different from the daughter of a wealthy merchant. It is a matter of your ability to create an image that expresses that difference [in a person’s class, etc.].

A fundamental rule of gidayu recitation is that you cannot use a “false” voice [created by artificial exaggeration or excessive changes in tonal quality, etc.]. When reciting a female character’s lines we don’t create a (falsely) feminine voice quality. You deliver the lines with your own voice. That doesn’t mean your natural speaking voice. When you learn to master the gidayu recitation (enunciation, volume, rhythm, etc.) you do it in your own voice [not a false voice]. Also, the volume of voice used in Bunraku gidayu recitation is larger than that of other Japanese traditional music. There is also what you might call a large octave range used. Since you have to recite in a number of different voices in the course of a Bunraku recitation, you have to train to expand your range of vocal variation.

In the old days people called it “training of the voice” and what it involves is training to acquire the skills that enable a person with a naturally small voice to be able to recite with a large voice, or a person with a naturally raspy voice trains to be able to recite parts with a clear and clean voice. The way we are taught to do this is that we are told to use all the voice we have without holding anything back. To speak using all the voice that is in us. Doing that makes you hoarse naturally. It is different from making yourself hoarse deliberately. Your voice gets hoarse from giving everything you have. You practice while mending your voice after it [naturally] gets hoarse, and this naturally increases the breadth and depth of your voice. They say that if you don’t go through this training process you will not get a gidayu voice. You don’t hold back to keep from getting hoarse but use all the voice that is in you. The great masters say that that is how you master something. - So, that is the way you trained your voice as well?

- That is what is expected of you, so if you don’t do it you are scolded or criticized. The shamisen player has gotten mad at me. It was when I performed Tempesuto Arashi nochi Hare – Tempest with Master Seiji Tsuruzawa on shamisen. As I was reciting, the shamisen suddenly became more intense and generated amazing power. When I went backstage after the performance, he said to me, “If you are going to take a rest, do it in the dressing room” [not on stage]. I thought I was putting everything into my performance, and of course I wasn’t slacking off, but the Master was saying that it wasn’t enough. He had showed me in effect, “Look at how much I am putting into my [shamisen] performance. You are not doing enough.” You perform as hard as you can, until you reach your limit and then you will gradually loosen the tension from there. You learn how to loosen the tension. This is something that only those who have taken themselves to the limit can learn. In other words, it is no good if you hold back before you reach your limit.

- Is that limit, that extreme, something that you can recognize when you reach it?

-

It is more often the case that you think you are giving the maximum effort you are capable of but someone then tells you that it is not enough. The gidayu recitation is a matter of power, of impact. That is true of all [the great masters] of the past. It would sound strange perhaps to say that the tayu has to have a big voice, but I would say that one of the requirements of gidayu is that the tayu has a voice that is large in scale. It is no good simply to be able to perform

joruri

skillfully in a small room. You have to be able to give a performance that sounds the same at the back of a large theater as it does in the front. That is one of the distinctive qualities of gidayu as a musical form. It is not true gidayu if it doesn’t have that big scale.

People often talk about “dimension” when talking about the difference in scale, and in modulation, between the performances of the great masters and ours [that haven’t reached that level]. It may be the same five seconds, but the way that five seconds sounds is different. There is more concentrated into masters’ five seconds, so in contrast our five seconds sound longer. If done skillfully it doesn’t sound that long. It is not a matter of the actual physical length or size. - Is there any other unique qualities of gidayu that you can tell us about?

- There is the exaggeration. We must over-express. In the case of an emotion like surprise, even though it might not be a natural action for the situation, the puppet is leaned backwards and the tayu makes an accompanying “Heeeh!” exclamation. We have to do that kind of over-action in order for it to be communicated to the audience that the [puppet] character is surprised. We use these methods for the puppets, the shamisen and the tayu, because the most important thing is that the contents of the play are communicated to the audience.

- For the tayu, the closest presence for you must be the shamisen. Which of you takes the lead when you perform?

- It depends on the performers’ respective positions. If it is the senior Master Seiji on the shamisen, I definitely follow his lead when we perform. If I am performing with a shamisen player who is younger than me, I will lead him in the performance. I think the ideal situation would be if the two performers are competing with each other in a give-and-take manner, however. When I perform with Master Seiji of course I follow his lead, but he tells me to come out more aggressively with the best I have and compete with him when we perform. I don’t think what I am capable of is close to real competition, but he tells me that I should recite with that kind of aggressive spirit.

- Do you ever try to synchronize your recitation with the movement of the puppets?

-

I never watch the puppets as I recite. Even in the case of the great master puppeteer, the late Tamao Yoshida, he always followed the lead of my recitation when he performed with the puppets. Young puppeteers maneuver the puppets with brisk movements, but Master Tamao’s dimension, his scale was so much larger that there is no comparison. When a famous master is performing there is an aura that projects naturally from the stage, and even without trying your own performance seems to come into sync with the master’s naturally.

Our Master Shimatayu tells us that we should sometimes take the time to go out and watch the puppets as we listen to the joruri (the story recitation along with the shamisen accompaniment) being performed. As a form of study we often listed to the joruri of the masters from the wings of the theater, but Master Shimatayu tells us to also go to a position where we can see the puppets sometimes and watch their movement as we listen to the joruri. Watching the kinds of movements the puppets are put through makes it easier to form image that inform our performance and lead naturally to good gidayu recitation. - May I ask what points you concentrate on when you practice [with a master]?

- Practice is important, but I feel that I learn most in the actual performances. When I am performing on stage with an accomplished master and I suddenly reach a point where I stumble and the recitation doesn’t come out properly, I feel so embarrassed that I wish I were dead. After that it makes me think why it happened. Was it a problem with the timing of my breaths? Was it because I over-exerted, or did I make the mistake because of the delivery of the previous lines? It is not that I am using the stage performances as a kind of practice, but more a matter of the fact that experiencing the all-or-nothing challenge of a stage performance where you have to give your all is the best form of training.

- In Bunraku there are also times when you have to fill in suddenly as a second for one of the older masters.

- It is not something you can do unless you are constantly listening to the performances of the masters, but that is also another form of learning. If you have listened to them on a regular basis you will be able to step in as a second and perform the recitation with some degree of proper form. When you do substitute as a second it is usually in a performance that is more important and difficult than the ones you usually do, so when you are asked to step in you can’t try to get out of it. And by doing it you get a firsthand experience of how difficult the roles of the masters are. If it were only for one stage you can get away with one mediocre performance. But, if it is for close to a month of performances, you have to maintain a certain level of quality every day. You can’t hold back in order to save something for the next day. You have to give it everything you have every day. What really makes the masters so great is that they are able to do that.

- It is often said that a tayu doesn’t reach his prime as an artist until his 60s or 70s. With all the experience you have gained until now, do you feel that you have begun to reach a certain level of strength as a performer?

-

No, I have never felt that way. The more I learn the higher the bar gets, so there is no time to think about how strong you have become as a performer. When you are young it is enough if you can just perform with energy in a big voice, but now that is not enough. There are always new challenges in front of you, like the criticism that you have not captured a character or that the performance has no heart. To a beginner, the master will only say things that the beginner will understand, but when you have been studying for ten years or more, these types of higher hurdles emerge.

It is all I can do just to keep tackling the issues that emerge in the process of performing stages with the best of my ability. One of the things that I am still corrected for constantly is my accent. Bunraku uses the language of Osaka during the Edo Period, and that presents a serious handicap for people like me raised in Eastern Japan and I still have trouble with it. I guess I am just going to have to keep living like this hoping that someday I will master the accent. - Being an instructor in the training, you are now in a situation where you are training the next generation of Bunraku performers, so you can’t spend all your time focusing on your own art. Is there a growth in the number of young people who want to study to become a tayu?

- It is hard to say. The shamisen player has his instrument, the puppeteers have their puppets, but the tayu only has his body, so his capabilities are revealed clearly. If the tayu is the weakest of the three it becomes very evident. We have tayu candidates in the training program, but I don’t know how much they actually like it. And, more immediate than that is the fact that young people today can’t sit in the formal seiza position (sitting on one’s calves). In the practice session they sit in seiza for three minutes and they being to moan and squirm (with their legs going to sleep). Ours is a profession where you have to sit in seiza position during the entire performance.

- That is a problem that has to be overcome even before any gidayu training can begin (laughs).

- It is a disappointing start. When I ask them, many say that they don’t have a tatami room in their house, so they have never experienced sitting in seiza position. It may be that today’s life environment has just reached a point where it isn’t conducive to the traditional arts in this sense.

- Today’s lifestyles may be much different from in the past but the themes of Bunraku plays such as the love between man and wife, self-sacrifice, love between parents and children, these are all universal themes for the human race.

- Yes, these are unchanging universal themes. The other day at the station there was a foreign mother and child and the child was fretting and squabbling because he couldn’t get something. It was a scene that made me feel that the fretting child is the same in Japan and abroad and today just as it was in olden days. I felt that our shared human essence is the same and unchanging.

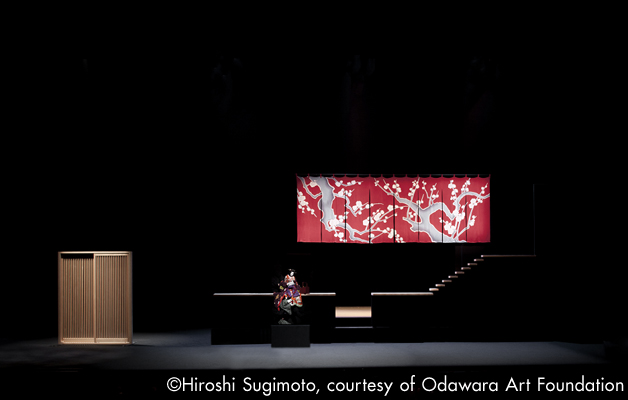

- For about one month beginning at the end of September, a “Sugimoto Bunraku” production adapted, directed and with stage art and video art by the contemporary artist Hiroshi Sugimoto will be touring Europe with performances in Madrid, Rome and Paris. May I ask what you think about overseas performances of Bunraku?

-

I often say that I wish people would stop thinking that foreign audiences can’t understand it if they don’t know the language. Look at opera. We don’t understand German or Italian but we still appreciate the good music and good staging of opera and we understand whether the scene is a sad one or not. Trying to understand the language or the storyline will only take much of the enjoyment out of it. If you just watch it with a sense for the feelings evoked, Bunraku is an art that can be thoroughly enjoyed by any audience. You could even go as far as to say that it is enough if people just enjoy the facial expressions of the tayu as he is reciting the gidayu. It is enough if people say, “I didn’t understand what he was saying but it was really impressive anyway.”

Of course there are things that can’t be understood because of cultural differences. There may be people who laugh because they find the movement of the puppets funny even though it is in the midst of a sad scene. But, the fact that they find it funny is proof that they were watching with interest. The fact that they reacted is because they felt something, and that is enough.

I believe that a stage [performance] is something that is created together with the audience. In the theater, we perform and the audience watches. There may be people who fall asleep during the performance, but even they are probably getting some kind of aural experience, and they are undeniably present with us in the same space. In an overseas performance that space happens to be in a foreign country but what we are performing is the same as what we perform in Japan. I believe it is natural that the way the performance is perceived will be different in different places. For us, we are happy if they understand even a small part of it, and if the performance sparks an interest in them, we couldn’t ask for anything more than that.